by Jon Dean

Sheffield Hallam University

Sociological Research Online, 20 (1), 2

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/20/1/2.html>

DOI: 10.5153/sro.3540

Received: 9 Jul 2014 | Accepted: 18 Nov 2014 | Published: 28 Feb 2015

This article presents findings from a creative qualitative study, where drawing was used as a methodological tool to investigate university students' awareness of homelessness. Previous research (Breeze and Dean 2012; 2013) has shown that homelessness charities often utilise stereotypical images in their fundraising campaigns, focusing on the arresting issue of rough sleeping (rooflessness) as opposed to other, more widespread experiences of homelessness. In drawing 'what homelessness looks like' the images students produce are often rooted in familiar local scenes - local roofless people they see regularly, or replications of common media images, with a tendency to depoliticise and individualise homelessness as a social issue. These drawings show striking similarities, common themes, and indicate a lack of critical engagement with the complex problems within personal homelessness narratives. The efficacy of the methodological approach is assessed, with the role creative methods such as drawing can play in stimulating critical discussion of issues, such as gender and the media, highlighted. The article also argues that such methods can play a role in critical pedagogy, encouraging deeply reflexive accounts of participants' behaviour and knowledge. In policy terms however, this article concludes that it would be a risk for homelessness charities to utilise less stereotypical images in their fundraising materials, as the findings suggest such images align with those in the minds of potential donors.

|

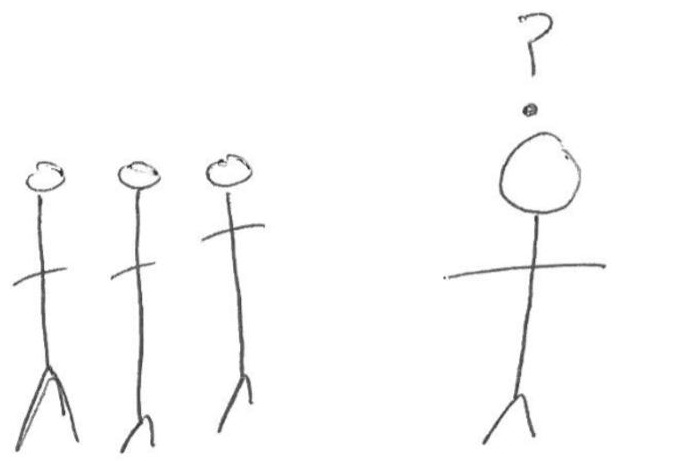

| Figure 1. Drawing by Ashleigh |

1.1 This research article has two objectives: to explore whether drawings of homelessness reinforce stereotypical representations and understandings of the issue, and to investigate the utility of creative methods as tools of critical pedagogy in teaching undergraduate students about social issues. The project stems from research with which the author was previously involved (Breeze and Dean 2012; 2013), exploring the views of service users at homelessness charities in the United Kingdom (UK) regarding the depiction and representation of homelessness and homeless people in fundraising campaigns. Over the course of a series of focus groups with service users at a range of charities providing services to homeless people, participants were shown a range of images used in homelessness fundraising materials.[1] Homeless participants told us that while they felt many of the campaigns utilised 'stereotypical' images to elicit 'sympathy payments' from potential donors, ultimately charities should continue to use these 'inaccurate' images, if they maximise charities' potential funding. The service users we spoke to were willing to be misrepresented for what they saw as the wider good. As one young man put it:

I think the money's the main thing, y'know what I mean? You can't have morals when you're homeless. (Breeze and Dean 2013: 20)

1.2 While perhaps a concerning finding, that already socially marginalized individuals were so willing to sacrifice any potential power they had over their own image, we were not surprised. Service users were generally found to be of the opinion that charities would not use such stereotypical and perhaps demeaning images if they were not successful in encouraging donations. This echoed previous findings; as Burman's (1994: 29) research into the images used by aid charities surmised, a 'poor starving Black child is so central to the idiom of charity appeals that aid campaigns depart from this convention only at the risk of prejudicing their income'. Adapting that sentiment for our own research purposes, we reasoned that, 'the dishevelled man in a duffel coat on the street is so central to the idiom of charity appeals, that homelessness campaigns depart from this convention only at the risk of prejudicing their income' (Breeze and Dean 2013: 16). Given Gladwell's (2006) 'blink' thesis, we argued that fundraising materials have to use images which closely correspond to the perception of homelessness that potential donors have 'in their heads'.

1.3 Accordingly, I wished to find out what that image was: is there a common image that individuals have in their heads regarding homelessness and, if so, what is it? To answer these questions, a creative methodological approach was used, which asked potential (student) donors to draw homelessness, and discuss their drawings. This article presents these findings, exploring where these images come from, and how participants account for them. The drawings, for example by Ashleigh (Figure 1, above), lead to discussions and analyses of the general level of understanding and awareness of homelessness among potential donors. But firstly, in order to be able to locate students' images of homelessness, and see if they are an 'accurate' representation of the realities of homelessness in the UK, the contextual realities of the extent, processes, and policies of homelessness should be understood.

|

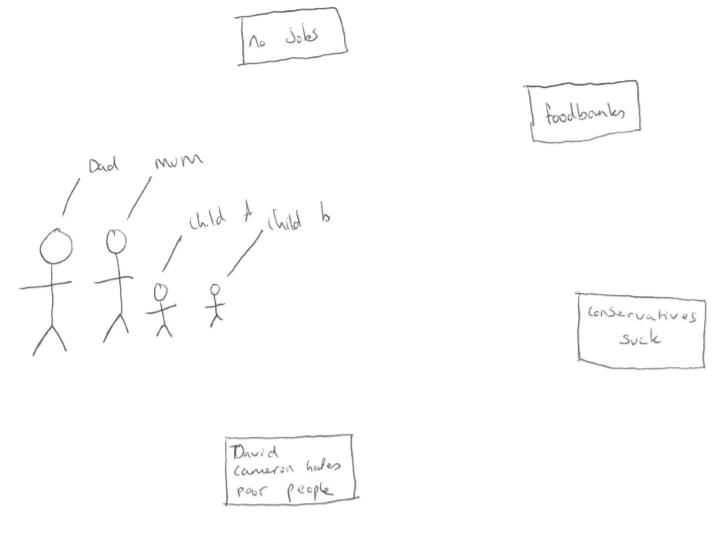

| Figure 2. Drawing by Nathan |

2.1 Homelessness is a contested term, the definition of which is subject to vested interests and policy agendas (Jacobs et al. 1999). As this article will show, homelessness is generally constructed narrowly in the public mind, a consequence of what Jacobs and his co-authors see as a purposeful abdication of responsibility by central government and policy practitioners. Yet technically homelessness is the broader term for four categories: rooflessness (rough sleeping), houselessness (being accommodated for the short-term in shelters or similar institutions), being in insecure housing (such as squats or refugee camps), or being in inadequate housing (without basic facilities) (Stearman 1998: 5). However it is being roofless that has become the defining conceptualisation of being homeless (Rosenthal 2000).

2.2 In the UK, the coalition government's program of economic austerity, including policy changes regarding social security and welfare such as the Spare Room Subsidy (the 'Bedroom Tax'), cuts in housing benefit, and reductions in support available to people aged under 35, alongside long-existing structural problems such as the UK housing market, low pay, and a stagnant jobs market, have all contributed to an increase in homelessness in recent years (Henley 2014). Over 111,000 families in England presented themselves as homeless to their Local Authority in 2013/14 (DCLG 2014a: 3), a 26 percent increase over four years (DCLG 2014b), with just over 52,000 households accepted as homeless (not all applications are accepted, with the 'intentionally' homeless, and young and single people with local family members unlikely to be housed). Other vital components in understanding routes into homelessness are family and relationship breakdown, individuals leaving the care system, offenders and ex-offenders, and ex-armed forces personnel (see Ravenhill 2008: 95-144). It should also be asserted that many homeless people have a series of interweaving complex needs, which makes the individualisation discussed throughout this article even more disconnected with the reality: the reasons for families presenting themselves as homeless are varied, interrelated, multifarious, and often structural rather than agential.

2.3 The end of shorthold tenancy is a key reason for presenting oneself as homeless, with parents unwilling to provide accommodation (16 percent) and violent relationship breakdown (12 percent) also prominent causes (DCLG 2014a: 6); 46 percent of accepted households are lone female parents (DCLG 2014a: 7). With reductions and restrictions in the Local Housing Allowance, the percentage of families presenting themselves as homeless to Local Authorities due to the end of assured shorthold tenancies increased from 15 percent to 26 percent in England, and from 15 percent to 35 percent in London, from May 2010 to September 2013 (DWP 2014: 77-8). Working with the ONS average of 2.3 persons per household in in the UK, this suggests that the UK's homeless population may sit somewhere between 120,000 and 250,000 individuals, including thousands of children.

2.4 Official estimates show there were 2,414 rough sleepers in England on any one night in Autumn 2013, an increase of 5 percent from 2012, and a significant 37 percent increase since 2010 (DCLG 2014c: 1). Further to this, 6,508 different people slept rough on the streets of London over the year 2013/14, a 61 percent increase from 2010/11 (CHAIN 2014: 3). Given the difficulty of measuring rough sleeping accurately, as none of the above data takes account of the 'hidden' homeless which includes people who may be sleeping in a squat or are inaccessible to outreach workers, this figure will always remain open to further debate (Thames Reach 2010;Williams 2010). However, given current measures, one in ten adults in the UK will experience homelessness at some point in their lives (Fitzpatrick et al. 2012), the average age of death for a homeless person is 47 years old, over 30 years below the national average (Thomas 2012), and up to 70 percent of homeless people have a mental health problem (St Mungo's 2009). Overall these statistics show that homelessness is a growing problem in the UK, but that rooflessness only makes up a small, if significant, part of that problem. [2]

2.5 Academically, homelessness has been a subject much studied by visual anthropologists and sociologists, utilising a variety of visual methods to explore the lived experience of being homeless. Anthropologists like Bourgois and Schonberg (2009) and Duneier (1999) have documented the lives of homeless people through photo-ethnography over more than a decade of study. Brown et al. (2012) created a graphic novel, telling the complex stories that make up vulnerable lives in comic book form as to encourage engagement with the issues and find a new audience for such research. Bukowski and Buetow (2011), Johnsen et al. (2008), Packard (2008), and Radley et al. (2006; 2010), have all used variants of photo-voice techniques (also called auto-photography, autodriving, reflexive photography, or photo-novella [Packard 2008: 64]), in which the researchers gave homeless participants disposable cameras to document their everyday experiences. On television, Cathy Come Home, Ken Loach's 1966 drama documentary, and more recently the BBC's Swansea: Living on the Streets in 2014, have sought to document and relate what it is like to live without secure housing. While Loach's film is remembered for its intensely politically-shaming approach, inspiring the establishment of several anti-homelessness charities (Rose 1998: 178; Henley 2014), the more relativist and potentially exploitative programme on Swansea passed without much comment, a parallel with much of the data presented below. These examples demonstrate how for over 50 years homelessness has been a subject which is constantly thought of in terms of striking visuals, a subject which is either seen or not seen. This importance of the visual when researching homelessness is central to understanding the methodological approach of this article.

3.1 In his book Creative Explorations, David Gauntlett (2007) discusses several different ways he has used visual and creative methods to explore identity creation. Groups of children were given the opportunity to video their responses to environmental problems, to see if children raised on a growing number of 'green' television programmes cared more about the environment (Gauntlett 2007: 93-104). He also asked children to draw pictures of celebrities as a way of understanding their feelings and values in regard to celebrity culture (Gauntlett 2007: 123-7). Perhaps most innovatively, Gauntlett conducted focus groups with a range of professionals (architects, social care workers, academics, and others) asking them to create models of their identity using Lego (Gauntlett 2007: 128-57), prompted by directions such as 'Create a model of how you feel on Monday morning', and 'Now transform that model to show how you feel on a Friday afternoon'. These methodological approaches have been shown as a potential way to get research participants to relax and exercise their creative skills in ways many of them may not ordinarily get to do. Ingram (2011) has used plasticine models to explore the cleft habitus of educationally successful, working-class boys in Belfast, and Abrahams and Ingram (2013) used similar techniques to encourage students to construct visual representations of how students encounter different fields. Across this approach to research there is the philosophy that 'doing something' creates both a connection to the research process and a sematic memory of participating in the process, and that the eye and the ear should be taken as seriously as the voice (Allan 2012; Back 2009; Hall et al. 2008; Pettinger and Lyon 2012). In that vein, I decided to apply this methodological approach in order to further investigate the hypothesis of our previous research: that fundraising images of homelessness were reflecting and reinforcing pre-existing images in the minds of potential donors. Research took place over a series of focus groups, lectures, and seminars.

3.2 This task began as a technique I utilised within my teaching at Sheffield Hallam University, particularly within research methods classes, to encourage students to think about communication and representation. In total, across teaching within both politics and sociology undergraduate courses, I have set this task to over 200 students. The images and conversations produced in the earliest seminars were not kept for posterity - it was not envisioned that a research project would emerge from them until discussions with colleagues persuaded me to collate the resources which students were creating and record our discussions about them. Further, permission to utilise these earlier images was not sought from participants at the time. However these initial applications of the task made me want to codify the position of students on this issue, with the possibility of in future opening this task up to disparate groups as Gauntlett (2007) does.

3.3 Data collection for the sample in focus here was conducted as follows. After asking participants to complete an ethics form, sessions began with a distribution of blank pieces of white A4 paper, and good-quality thin black marker pens. I would tell participants that they had five minutes to 'draw what homelessness looks like'. These were the exact words I used in each session, and would be repeated two or three times. No more instructions were provided, and students were encouraged not to look at each other's drawings or talk about the task while they were completing it. Often at this stage one or two students would say 'But I'm crap at drawing!', or something similar. At this point students would be reassured that in these drawings there is no interest in an individuals' artistic skill, but that the point of the task is to encourage students to think creatively, and to uncover individuals' initial internal representations of homelessness. After the drawings are finished, I ask the students to thoroughly explain what they have created, and explore why they chose to address the task in the way they did.

3.4 The data from which this article draws comes from two specific samples collected in late spring 2014: firstly, a set of images drawn by 28 students (15 female and 13 male, all 20 or 21 years of age) as part of a third-year charity studies module for sociology and politics students within a lecture on charity advertising and fundraising techniques. In this first sample, participants were asked to draw their images and then write a one-page essay detailing why they had chosen to draw the image that they had. Secondly, a set of three focus groups with a total of 13 students (10 male and three female, the majority of whom were 18 or 19 years of age) were conducted. Focus group participants were first-year sociology and politics students (two groups of five students and one group of three students), and after completing their drawings participants were asked to reflect on their drawings verbally in a conversation which was recorded on a digital voice recorder. As a way of utilising visual methods as a tool of critical pedagogy, focus groups were thought of by the researcher as both a research experience and also as a learning experience, where the current state of homelessness in the UK was explained and discussed in light of what students' drawings and explanations of those drawings, revealed about their current level of knowledge of homelessness as a social problem. These focus groups lasted between 40 and 45 minutes and were transcribed. After the data was collected, analysis took place first quantitatively, where the drawings were coded for their contents (see Table 1 below), and then qualitatively, where transcripts and reflexive accounts were examined for common themes, with the drawings taking on a deeper meaning as I read and listened back to the participants descriptions of them. In line with standard ethical practice the names of all research participants and specific locations and organisations mentioned by participants have been anonymised.

3.5 Drawing only from a sample of student research participants, and seeing them as emblematic of the wider pool of potential donors, raises questions about class and age dynamics and the wider generalisability of findings. Undertaking this project with a wider range of participants would in all likelihood produce different responses, with, potentially, older participants having a more nuanced understanding of homelessness, although this is certainly not a given. Completing the task with individuals with experiences (either personal or familial) of homelessness could also provide a valuable comparison. In terms of social class, while one student called Louis raised the issue of being from quite a 'middle-class area', class dynamics were not obvious in the discussions of the drawings. While specific class and background data was not collected from participants, Sheffield Hallam University, as a former polytechnic university, recruits students who would traditionally be thought of as upper-working-class/lower-middle-class, with internal university data showing 40 percent of students are from NS-SEC social classes 4-7, and 97 percent of students educated at state schools or colleges.

|

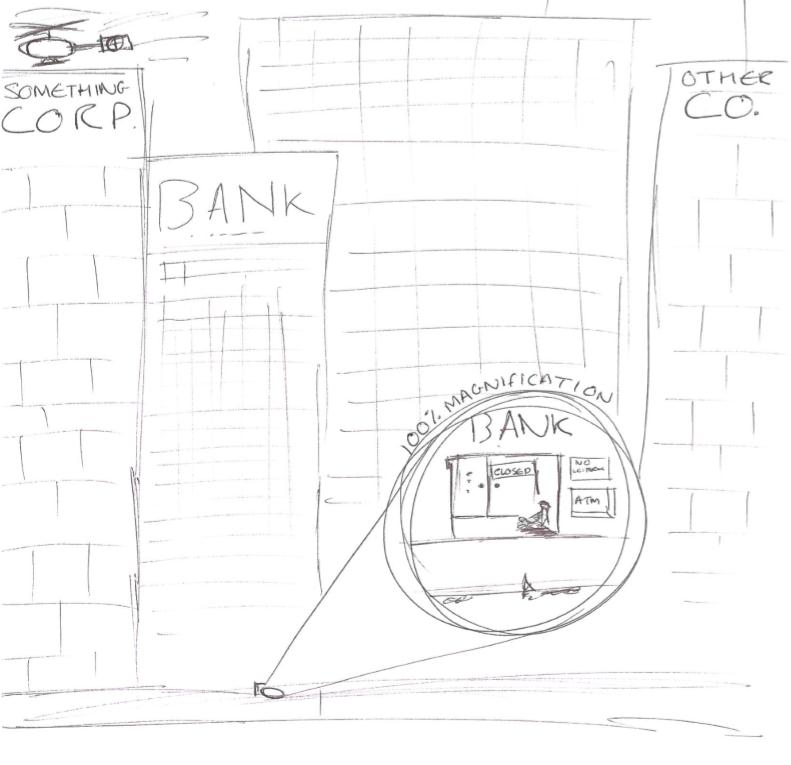

| Figure 3. Drawing by Edward |

4.1 After students put down their pens, and are asked to hold up their paper and explain why they have drawn what they have, what becomes immediately apparent is how similar the vast majority of images are. Table 1 below presents a quantitative assessment of the contents of the images:

| Table 1: Elements contained within the images (n=41) | |

| Element | Frequency |

| Male figure | 24 |

| Female figure | 3 |

| Figure of unidentifiable gender | 10 |

| Family | 4 |

| Dishevelled appearance | 25 |

| Rooflessness | 31 |

| Begging / being given money | 18 |

| Dog | 14 |

| Alcohol | 12 |

| Smoking | 4 |

| Illegal drugs | 6 |

4.2 In all 41 images, participants drew a person or people, with 24 drawings including men and three including women, with four images of a family unit of one man, one women, and two children (with 10 images including stick people where the gender was unidentifiable). While the heteronormativity of these images is interesting, it is the gender imbalance that is most immediately striking. May et al (2007) have argued that female homelessness is much less likely to be visible, an assertion backed up by the findings here, with the archetypal image of the bearded man clearly prominent in participants' thoughts when they were completing the task.[3] Further to this, and included even more commonly than a male figure, was the notion of a dishevelled appearance, represented by torn or dirty clothes, lines emanating from a figure indicating body odour, dirty or missing teeth, or unkempt hair with long beards or stubble, among other tropes.

4.3 Most frequently represented within the drawings however was rooflessness, with over three-quarters of participants drawing a scene depicting either a figure or figures sleeping rough. These were often on high streets, in alleyways, in bus shelters, or in underpasses. Nearly half of the images presented either an individual asking for money, usually through a plate or cup for collecting coins, or being given money by a passer-by: only two participants drew a roofless figure being helped beyond this, with Yvan and Louis drawing a worker from the Salvation Army bringing food to a group of homeless people. Reflecting on the reason for this inclusion, Louis said, 'the general public see the homeless as faceless, but the Salvation Army and the people who work for these charities are more likely to see them as identified individuals.' The notions of having a dog for company and alcohol consumption were prevalent in the drawings, but scenes of smoking and illegal drugs were relatively rare.

4.4 When asked to describe the figures they had drawn, participants commonly used phrases such as 'quite sad' and 'neglected' (Ashleigh), and 'vulnerable and cold' and 'the odd one out' (Nathan), 'people who have not got any smiles on their faces' (Gareth), and generally scenes which depict 'a sense of sadness' (Eric). Enrique said his image showed:

… how homeless people are perceived as being separate from society. I read an article once where they said, 'A homeless person is like they are standing behind a pane of glass, completely separating them from everybody walking past.' It is the isolation of it all.

4.5 Isolation and loneliness were key concepts that arose out of participants' rationales for drawing what they did. The banter and support that could come from being in a hostel that Breeze and myself experienced in our research, or the support and sense of community provided by friends in the hostels that Hall (2003) found in his ethnographic study were all absent, due to the focus on street homelessness (similar support can be found on the street in the work of Bourgois and Schonberg [2009] and Duneier [1999]). In none of the drawings does the idea that a homeless person may have a job or be involved in education or training get represented.

4.6 The three images above, from Ashleigh (Figure 1), Nathan (Figure 2), and Edward (Figure 3), drawn independently, show incredible consistency, from the homeless men produced within them, to the situations they depict, even in the angle of the lines used to depict a street scene. All feature bearded men with unkempt hair surrounded by a few untidy belongings. Two of the images include either faceless passers-by, or passers-by ignoring the homeless person at the drawing's centre, and two images feature begging of some description, and are representative of many of the drawings, and are very similar to the Salvation Army fundraising images reproduced in our previous research (Breeze and Dean 2013: 22).

4.7 I have been surprised in this project that so few participants tackle the task in an abstract or particularly original way, given the prevalence of metaphor in Gauntlett's (2007: 185) work. Of the 41 drawings in this sample, perhaps only Yelena's (Figure 4, below) could be said to be abstract, detailing that while the figure is the same as other people, there is confusion as to why they are different and isolated from the rest of society. Yet even here, the focus is on the personal consequences of homelessness, not the structural causes, or the wider societal consequences of the issue.

|

| Figure 4. Drawing by Yelena |

4.8 As many teachers and lecturers will be aware, often in seminars or classes when a group of students are asked a question, there will be a pause or quiet moment before someone offers an answer. This was not my experience in these research sessions. Often before I had finished setting out the task, participants would bend over their paper to start drawing. Whereas Gauntlett (2007: 185-6) asserts that participants often need a reflexive 'incubation' period in order to instigate creativity, the nature of this task was to gather the instantaneous image. Asked why they were able to draw these images so quickly, without (seemingly) really thinking about what they were drawing, participants' replies focused on the uniformity of homelessness in their eyes:

Cos that's the only face you see of homelessness, you don't really see anything behind the scenes, like the soup runs or anything. (Edward)

4.9 Students were aware of the 'other world' of homelessness: 'the shelters, and like the [local] soup run, but that's not really in the media, you don't see that' said Edward. When it was put to Edward that he clearly did know of this other world of supportive charities and volunteers, but that he had still chosen to draw a roofless, isolated individual, he replied he did not know why he made that choice. In trying to answer, Nathan felt that the above images were the students' reproductions of mainstream representation:

Just a mainstream depiction of it really [where] if you're just walking about and you're not putting yourself out there to help homelessness, however terrible it might be, that's the side of it you see really. So that's why I drew that I guess.

4.10 These quotes and others reveal students' own admission of a lack of knowledge and understanding of the realities of homelessness, with many asserting that the media has a key role in how they visualise the issue. Specific media that were mentioned in focus groups were the BBC news programme Panorama and the BBC news website, the soap opera Coronation Street, (a storyline of which at the time of the research involved a young girl who had been in a hostel), the music video for Ed Sheeran's song 'The A Team', the film Batman Begins and the video game Grand Theft Auto ('You walk past someone on the street just there – it's being reaffirmed in everything!' [Manny]). The cult figure of the 'American hobo', referenced separately by Louis and Stephen, was also present in drawings.

4.11 Participants were quite critical of the broadcast media for not covering homelessness other than rooflessness, and asserted that they thought the media were unlikely to break from narrow depictions of homelessness, which 'contorted' perceptions (Rebecca):

The media portray homeless people generally, and you touched on it, as drug addicts and alcoholics, which tends to point to men. You don't see much the side of losing the job and the whole domino effect of why some people become addicted to alcohol and drugs. (Enrique)

4.12 Again, this shows an awareness of wider issues, but ones participants chose not to represent. When the media was raised as a possible reason for participants drawing the images they did, many reasoned that there was not enough media focus on the issue of homelessness, and when there was, the coverage was often critiqued for being overwhelmingly negative.

4.13 These views correspond with much of the analysis of the media within the critical homelessness policy literature. Hutson and Liddiard (1994: 75) write of how homelessness is often presented in the media as 'an unfamiliar and mysterious problem' despite being 'quite visible and not physically hidden'; an issue which, in the guise of rough sleeping and street begging, people are often strikingly exposed to but rarely at a level which creates engagement or understanding. Strategically, Beresford (1979) argues, the media divorce the general public from their own experiences of homelessness (such as experiences of temporary or poor-quality accommodation), and as such impose their own meaning on the issue, creating or reinforcing an artificial divide between the homeless and potential donors. This present research supports this thesis.

4.14 Participants predominantly drew homeless people that they 'know', drawing on recent experiences, either 'the homeless guy from my home town' or someone they saw regularly in their everyday lives:

My drawing is based on the 'homeless' people I see in the city centre on North Street every day I leave the flat. (Elizabeth)

I can't remember the last time I walked through the underpass at the bottom of South Road (at the roundabout) and didn't see someone sat on the floor asking for spare change. (Natalie)

I tried to depict an image of the homeless man who sits outside Burger Stop everyday with his dog, with a small bag for passers-by to chuck in loose change. (Yilda)

I have drawn the homeless person in front of Videotainment as I see this person daily on the way to university. He always has a dog, like most homeless people. (Terry)

4.15 The ubiquity of images from the UK is of interest, with participants only occasionally referencing Paris or New York as cities with significant homelessness problems, and with the issues of international aid and refugee camps never arising in drawings or discussions (excluding Stearman's [1998]work, the academic literature on the subject generally makes the same distinction). Instead, students took a local, personalised focus, and were keen to recount their encounters with homeless people, which usually centred around being asked for money on the streets, often at cash points or in the queues for nightclubs. Some expressed how this made them feel uncomfortable, but the more prominent feeling was of how pitiful these exchanges often were:

Last week, I was in town quite late because I came from the train station. A homeless guy approached me and he was like: "I have got nowhere to sleep tonight. Do you have any change at all?" I was going to ignore him, but I just couldn't. I gave him £2, but I had £10 in my purse. After I gave him the £2, I was like: "I don't know what that can do, really, but just take it." I felt a bit bad, like maybe I should have given him the £10 because I wasn't really using it. (Rebecca)

Walking down East Street, quite a few times, actually, I have had the same two fellas come up to me, approach me and ask me for money. It sounds cruel, but, often, in my mind, I am like: "Oh, I will just give them some money so that they leave me alone."… I feel bad for thinking that way, but it is 'them and us'. It is cruel, and I hate myself for it. (Stephen)

|

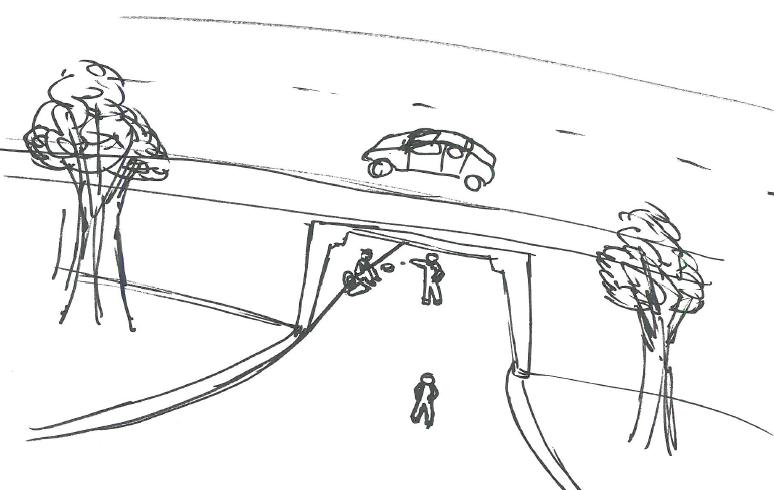

| Figure 5. Drawing by Lillian |

4.16 One way therefore of analysing participants' responses to the task is to see their individualisation and personalisation of homelessness as a symptom of a wider social conceptualisation which frames homelessness not as a social, structural issue, but as one rooted in individual agency. While any image of homelessness could be said to be political, very few of the images drawn by students could be classified as overtly commenting on structural issues or political causes. Instead, in their response to the task students were likely to individualise the issue of homelessness, focusing on its impact on the life of a single, roofless man, rather than wider social contexts. Only two drawings located homelessness within a wider narrative of structural inequality, those of Lillian (Figure 5, above) and Martin (Figure 6, below).

|

| Figure 6. Drawing by Martin |

4.17 Martin's drawing focuses on the alienation from capitalism of one homeless individual, drawn to be puny and insignificant when compared to the skyscrapers housing 'Something Corp', 'Other Co.', and a large bank. In his explanation, Martin said he wanted to stress the inaccessible nature of both capital and the capital (London), through concentrating on the comparison between wealth and poverty. In contrast to Marcuse's (1989: 216) reflection on urban inequality a quarter of a century ago, that 'the poverty of the homeless challenges the pursuit of wealth as an end in itself; greed becomes less acceptable', Martin's drawing argues that the pursuit of wealth clearly overrides the unacceptability of the poverty of the homeless. In fact it is the homeless who are aesthetically unacceptable to the wealthy city, as Blau's (1992: 4) vivid description of 'street sweeps', Zukin's (1995: xiv) notion of the sanitised urban space ('domestication by cappuccino'), and the wider critical geography literature on gentrification testify (see Andersson and Valentine 2014).

4.18 In a similar vein, Lillian's drawing, the only one to refer to organised party politics includes the phrases 'Conservatives suck', and 'David Cameron hates poor people', including a drawing of a family who have 'no jobs' and are reliant on food banks, experiences which she said in her view were increasing, with more families and children losing access to secure or permanent housing. While there is a clear difference between these two images in their level of detail, artistic imagination, and metaphorical representation of the problem, it was surprising to me as a lecturer that they were the only participants to tackle the task in this way, given that all participants were studying for undergraduate degrees in sociology and politics.

4.19 As is common in discussions of homelessness, public debate becomes organised around the dichotomous individual causes (alcoholism, drug addiction, crime, laziness) against structural causes (family breakdown, unemployment, violence) (Rosenthal 2000). Participants ably demonstrated understanding of how such arguments are promulgated socially within family settings:

Luke: My sister says to me all the time, "Don't give a homeless man money because he will use it for drugs."

Jon Dean: Do you think that is always true?

Luke: I don't know, but it is something that has just been drilled into me since I was quite young. If I am out with my family, or my dad in particular, they will say, "Never give." He is a Tory. He will say, "It is his own fault. He is a druggie. Don't give him any money."

4.20 As Hutson (1999: 10), referencing the famous example of unemployment in large populations put forward by C. Wright Mills, writes, '[a]lthough the public messages about homelessness may include individual blame and social pathology, both the creation and the solution of homelessness lie with public policies.' But the depoliticised drawings of participants could be said to be a victory for the strategy inherent in homelessness policy and public discourse in general over 25 years. Somerville (1999: 36-9) has argued that such depoliticisation occurs because policy practitioners and politicians in the UK have worked since the late 1980s to classify homelessness, and encourage it to be thought of publically, as specific temporary aberrations rather than as a result of fundamental structural problems. At the centre of such a strategy is a particular focus on assuming the problem of homelessness was the fault of the homeless themselves. Participants recognise these dichotomies in their explanations of homelessness, and express empathetic concern and guilt as the stereotypical nature of their depictions of homelessness become clear to them.

5.1 In their visual anthropological study of homeless heroin users in San Francisco, Bourgois and Schonberg (2009: 9) admit their concern at presenting images of suffering, because they fear these may fuel a 'voyeuristic pornography' of everyday violence. Such a fear echoes Ignatieff's (1999: 11; Ray 2013) label of Western audiences as 'voyeurs of the suffering of others' and Brendan Gormley's (former Chief Executive of the Disasters Emergency Committee) critique of the 'disaster pornography' used by charities requesting donations in the wake of the Haiti earthquake in 2010 (see Breeze and Dean 2012). As a response, Bourgois and Schonberg apply themselves to providing the biographical, social, and cultural contexts for such graphic images and descriptions, reporting their negotiations of unstable emotions in the process. Wilkinson's (2013: 272) analysis of this approach is to highlight that drawing attention to such social suffering requires both a commitment to 'nourishing moral sentiment' and an understanding that an element of negation of the humanitarian compulsion is required to provoke critical thinking about the moral and political responsibility 'we' bear towards 'others'. Importantly, Wilkinson directs us to Bourgois and Schonberg's view that it is the most hopeless, emotional and unstable elements in their work which are the most capable of provoking recognition, responsibility, and action. The idea of guilt-tripping or shaming people into either action or critical engagement is not one that appeals, but could be argued to be at the heart of the symbolic power and violence (Bourdieu 1984) practiced by all charity fundraising material.

5.2 From a social justice perspective, where we seek to tackle the inequality that causes homelessness and alleviate the suffering which it causes, then the education of citizens in a position to do something about it, whether it be moving from the status of potential donor to committed donor, volunteering with an appropriate organisation, or campaigning to change policy, is an important part of such a strategy. Student participants in this research often expressed guilt, shame, or remorse at the content of the images they drew:

I think that I drew a cloud as well was partly because, say, if I have been on a night-out and it has been pissing it down, you have got the homeless people shivering and absolutely drenched. That is an image that often sticks in my head. You feel guilty because you are like: "Well, I have got a bed to go to and I am going to be dry." (Stephen)

Talking about homelessness like this, we all feel sympathy for people who are homeless, but how many of us actually give to the homeless? I feel awful when I give change in my purse which adds up to about 50p or whatever. What can that do, really? I wish I could give more, but, as a student, I can't really give that much. (Emma)

5.3There was also mild personal disgust at some of the terminology of participants' discussions:

It is very interesting how we are talking about this situation. It is very much not part of our society: "I have seen one of those." We are completely separate from these people. (Enrique)

5.4 Freire's (1970; 2005) focus on the political underpinnings of education, seeing it as a liberating process which teaches people to be critical thinkers, sees this critical consciousness as a key tool in stimulating community-based action. This practice of 'conscientisation', where through questioning everyday experiences it is possible to make critical connections, in turn exposes the injustices and contradictions that exist in social life. In such a paradigm, education requires a dialogue between educator and student, where:

[t]he role of the educator is to present codifications - photos, video, song, drama, verse, prose - which decontextualize a relevant aspect of everyday reality. By skilfully posing questions, rather than giving answers, critical connections emerge from the dialogue. (Ledwith 2001: 178 [emphasis in original])

5.5 The questions 'why have you drawn this?' and 'what do you think it says about society that you have drawn this?' are questions which arouse conflict and, as a result, allow critical connections to emerge.

5.6 In such a Freierian schema, the student is given confidence to challenge for social change. On a small scale, the discussion about guilt and the inability to sufficiently tackle homelessness which emanates from this methodological task displays such a philosophy. A didactic lecture which presents the facts and figures of homelessness in the UK and around the world, with some colour added through presenting elements from anthropology or documentary films, would not, it is argued, be as effective in challenging students' pre-conceived ideas about the realities of homelessness. The process of drawing literally draws these out, providing a base on which to build critique, using visual methods as an opportunity to critique collaboratively as they are well-placed to do (Thomson 2008). This critical thinking occurs both about the realities of homelessness ('I thought there would be more people who slept on the streets' [Ashleigh]), and about the impact of social structures and institutions, such as the media, on students' conceptions ('The worst of it is all we see, and that is what society preys on. That is why it has had such a negative impact on us.' [Enrique]).

|

| Figure 7. Drawing by Eric |

I apologise for my drawing ability! (Louis)

Jon Dean: Why did you choose to draw that? Is that the first thing that came into your head?

Manny: No. Firstly I thought I could draw someone who was lying on the street, but I thought 'I am not that great at drawing!' (Laughter)

5.7 Stephen was one of only three participants who drew a female figure, who was not part of a family unit. When asked why this was, he replied that this was a conscious choice made because he had witnessed an argument on a busy city centre street a few days previously involving a woman who 'sometimes sits outside Supersave… The security guard came out, telling her to move':

Jon Dean: While you were drawing you had the conscious idea, 'This is not the stereotypical image. I know I am drawing something that is not common'?

Stephen: Yes, I did think that. I thought I would draw a female just because I knew it [the encounter] did happen and it would be possibly different to what everyone else would do.

5.8 Stephen's point here challenges the method, showing how such an approach cannot necessarily hope to draw out an individuals' 'overall' view of an issue, but is by its nature, as is often the case with visual methods, a singular, interpretive 'snapshot'. Stephen explicitly chose to draw a woman because of the singularity of his recent experience, and with the assumed knowledge that this would make his drawing different from the others. While not a major limitation, this small incident does show the temporal importance of when the research is carried out, with events, either social or personal to the participant, having a direct impact on the images drawn. The repertoire of skills and knowledges that participants bring to the task is not neutral, particularly their experience of various media as Buckingham and de Block (2008: 141) address in their critique of participatory visual methods (see also Allan's [2012] critical review of the field). This is also seen in the concerns that Louis and Manny are expressing above, that performative and creative methods which have arisen out of a belief in democratic and empowering research can actually be exclusionary (Robinson and Gillies 2012: 87): here this exclusion is centred on drawing ability.

5.9 In this vein, the task could be criticised for being rather inflexible; as Spencer (2010) has written of his work on mapping exercises, researcher adaptability and remaining fluid are important so as not to isolate participants who feel they cannot draw or do not want to draw. I have yet to experience someone refusing or expressing that they feel unable to participate in this way, but it should be recognised as a potential limitation; within such methods it must be recognised that what can be made of the data is tied up in the means of producing them (Radley et al. 2010). Correspondingly, there is awareness that if participants were given different directions for the task, for example being asked to 'draw an image which represents homelessness, or 'draw an image which sums up your knowledge or experience of homelessness', then it is almost certain that many would have chosen different ways to draw their answers, just as differently phrased or ordered interview questions could provide different answers (Schuman and Presser 1981; Pew Research n.d.). Testing this thesis is worthy of future study, and will be something investigated with students in forthcoming sessions.

5.10 Another practical concern here is that participants may use the task as an opportunity to draw the most awful image they can think of. If one of the central tenets of Gauntlett's work is to allow creativity to flourish among individuals who do not often get to be creative, and there is no other space on our degree for our students to test their drawing skills, then they may use the task as an opportunity to 'let rip' . Therefore their drawings may not be representations of what participants actually think homelessness 'looks like'. While this does not invalidate the research, just as participants may not be truthful or accurate in interviews or focus groups, or behave naturally during participant-observations, it does reaffirm the need for the verbal explanation post-drawing: the explanations and discussions gathered in the three focus groups especially provides the opportunity to generate richer and thicker data. It is noticeable that in the majority of applications of these creative methods (for example Gauntlett 2007; Ingram 2011; Abrahams and Ingram 2013; Pimlott-Wilson 2012) there remains the need to combine innovative approaches with more established qualitative research practices.

5.11 Another obvious avenue for research in this vein would be with different societal and charity sector issues, exploring what cancer, or animal cruelty, or child abuse 'look like', to see if these issues, also prominent in fundraising appeals across the UK, reproduce reportedly media-driven stereotypical images from participants, and whether the drawings are as homogenous and non-abstract (the Fun with Cancer Patients project is one academic intervention in this vein: see http://www.funwithcancerpatients.com/). Given Joel (1992: 4) assertion that the 'single most significant attribute of homelessness is its visibility', a state of affairs which interrupts the rhythms of modern, capitalist societies and undermines the rules governing public spaces, we should expect homelessness to perhaps draw out images which are more 'other'. Mead's concept of the 'generalized other', where a 'constellation of acts [are] collapsed into symbols' (Richardson 1989: 174), suggests that 'the reality of what people can see is determined greatly by what they can handle' (Mead 1972: 105). To take Mead literally, these drawings suggest that perhaps participants cannot handle the realities or complexities of homelessness so reduce it to stereotype and caricature, reproducing only common representations, even though the participants' contributions in the following discussions clearly show a greater knowledge about the subject, as well as emotional relationships with the issue, driven by care, guilt, worry and distress.

5.12 If the stereotyped and unrepresentative imagery associated with homelessness is a problem, then this method presents one small way of challenging that hegemony. It may be that such a task forms the basis of toolkits for homelessness charities when conducting outreach workshops and similar events in their local communities, and this, as an act of public sociology will be something I work to develop in the near future.

6.1 The research objectives which inspired this project were to investigate what image potential donors (here, admittedly, represented narrowly by students) have of homelessness in their heads, and explore the efficacy of drawing and creative methods as tools of critical pedagogy.

6.2 Regarding the methodological approach, further evidence has been produced which demonstrates that by merging the visual and the verbal, and integrating novel creative tasks, researchers have the opportunity to build up a more nuanced understanding of how participants conceptualise problems such as social inequalities. Research participants are able to make substantive points about gender, the media, stereotyping, and their own conduct in social life through such methodologies. If advertising is about the snap judgement and snap decision (Gladwell 2006), for example to donate or not, then asking people to express what homelessness means to them instantly through drawing can be seen to be an accurate and effective method to understand which fundraising images may chime with public perceptions. Visual methodologies of this kind can tap into dominant value systems and demonstrate the underlying values of and reasoning behind campaign iconography. However we should be wary of claiming these methods produce superior knowledge (Lomax 2012): they produce different knowledge differently. Researchers across disciplines should incorporate such methods into appropriate spaces within the methodological canon, and not see them as a rejection of, or replacement for, the methodological canon. And until new, creative and inherently flexible methods such as those used in this present study become commonplace (and are no longer described as 'innovative'), it remains a vital responsibility of researchers to be thorough in their reflexive critique of their own practice, and to ensure that such research projects deliver on their practical and theoretical intentions (see the edited collection introduced by Robinson and Gillies 2012). This is especially important so that researchers can test out previous findings and conduct restudies which ultimately reinforce, reinterpret, or reject theories emanating from such studies.

6.3 In terms of the data produced, the findings clearly show images are centred on patriarchal, isolated, roofless, and individualised depictions of homelessness as a social issue. This correlates with the hypothesis put forward by Breeze and myself (2013), that it is a risk for homelessness charities to divert significantly from the images which have historically formed the basis of a large proportion of their campaigns. Given the homogeneity of the images produced in this research, and further studies which show complex, contextual information can lessen the impact of a fundraising campaign (Small and Verrochi 2009: 785-6), we could argue that charities are acting rationally in continuing to fundraise in such a way, even though in rooflessness they are focusing on a relatively small element of the overall problem of homelessness: 'the public must be given what they appear to want: images of charitable beneficiaries that fit comfortably with widely held stereotypes about 'victims' and which prompt the largest amount of donations' (Breeze and Dean 2013: 12).

6.4 Charities and agencies have the power and ability to frame narratives and images of social issues such as homelessness (Hutson and Liddiard 1994: 98), with publicity often a charities' 'lifeblood', crucial for fundraising success (Deacon 1999: 51). In this light, it may be that we see the findings of this research as potentially worrying, providing a rationale for fundraising strategies which continue to use stereotypical images and communicate only a small element of the realities of homelessness. The evidence presented above suggests that stereotypical, individualised, and depoliticised images are those most likely to stimulate recognition and, potentially, donations from the general public, yet perpetuate inaccurate understandings and a lack of empathy. This unfortunate contradiction reflects Somerville's (2013: 404) assertion that homelessness charities (the 'homelessness industry') are riven by internal contradictions, a source of both division and unity as they seek to balance educating and engaging the public, continuing to exist and provide services and ceasing needing to exist and provide services.

6.5 Further to this, social researchers studying welfare stigma, such as the recent section in Sociological Research Online (http://www.socresonline.org.uk/19/3/contents.html) in response to the UK television programme 'Benefits Street', and campaigning research against inaccurate government claims of 'generations of worklessness' (Shildrick et al. 2012a; 2012b), need to extend their gaze to the issues of stigma towards homelessness. This should take the form of presenting the realities of the issue to a variety of (potential donor) publics, and repoliticising homelessness as an issue, as the depoliticisation and individualisation of homelessness seem to be vital impediments to undertaking any structural reforms which would lessen it.

1 Examples of such images can be found in Breeze and Dean (2012, 2013), at the Adhunt blog ( http://adhunt.blogspot.co.uk/2010/05/samusocial-asphaltisation.html) which shows a variety of images used by the French homelessness organisation Samusocial, in Third Sector magazine's dissection of a recent Thames Link campaign ( http://www.thirdsector.co.uk/case-study-thames-reach-persistent-campaign-worked/communications/article/1050651), and elsewhere.

2For recent comprehensive accounts of homelessness, including routes into homelessness and the policy agenda, see Ravenhill (2008) and Somerville (2013).

3McCarthy's (2013a; 2013b) recent work on participatory feminist research methods and homelessness explicitly explore the role of gender in constructing identity as a homeless individual.

ABRAHAMS, J and Ingram, N. (2013) The chameleon habitus: Exploring students' negotiations of multiple fields, Sociological Research Online, 18(4). http://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/4/21.html. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.5153/sro.3189]

ALLAN, A. (2012) Power, participation and privilege - Methodological lessons from using visual methods in research with young people, Sociological Research Online, 17(3). http://www.socresonline.org.uk/17/3/8.html. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.5153/sro.2662]

ANDERSSON, J and Valentine, G. (2014) Picturing the poor: Fundraising and the depoliticisation of homelessness. Social & Cultural Geography, DOI: 10.1080/14649365.2014.950688 [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.950688]

BACK, L. (2009). Researching community and its moral projects. Twenty-First Century Society: Journal of the Academy of the Social Sciences, 4(2): p.201-214.

BERESFORD, P. (1979) The public presentation of vagrancy, in Cook, T. (ed) Vagrancy: Some New Perspectives. London, UK: Academic Press.

BLAU, J. (1992) The Visible Poor. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

BOURDIEU, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (trans. R Nice). London, UK: Routledge.

BOURGOIS, P and Schonberg, J. (2009) Righteous Dopefiend. London, UK: University of California Press.

BREEZE, B and Dean, J. (2012) Pictures of Me: user views on their representation in homelessness fundraising appeals. International Journal of Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17(2): p.132-143. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1417]

BREEZE, B and Dean, J. (2013) User Views of Fundraising: a study of charitable beneficiaries' opinion of their representation in appeals. London, UK: Alliance.

BROWN, P, Somerville, P, Scullion, L, Morris, G, and Dahl, S. (2012) Somewhere Nowhere: Lives without homes. Salford, UK: Salford Housing and Urban Studies Unit.

BUCKINGHAM, D. and de Block, L. (2008) Global Children, Global Media: Migration, Media and Childhood. Buckingham, UK: Palgrave.

BUKOWSKI, K and Buetow, S. (2011) Making the invisible visible: a photovoice exploration of homeless women's health and lives in central Auckland, Social Science & Medicine 72: p.739-46. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.029]

BURMAN, E. (1994) 'Poor children: charity appeals and ideologies of childhood'. Changes: An International Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy 12(1): p.29-36.

CHAIN (2014) Street to home. http://www.broadwaylondon.org/CHAIN/Reports/ S2h2014/S2H%20full_2013-14%20final.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2014.

DCLG (2014a) Statutory homelessness: January to March Quarter 2014 England (Revised). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/339003/Statutory_Homelessness_1st_Quarter__Jan_-_March__2014_England_20140729.pdf. Accessed 9 September 2014.

DCLG (2014b) Table 770: Decisions taken by local authorities under the 1996 Housing Acton applications from eligible households. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/323960/Copy_of_Table_770.xls. Accessed 3 July 2014.

DCLG (2014c) Rough sleeping statistics - autumn 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/284024/Rough_Sleeping_Statistics_England_-_Autumn_2013.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2014.

DEACON, D. (1999) Charitable images: The construction of voluntary sector news, in Franklin, B. (ed) Social Policy, The Media and Misrepresentation.London, UK: Routledge.

DWP (2014) The impact of recent reforms to Local Housing Allowance: Differences by place. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/329794/rr873-lha-impact-of- recent-reforms-differences-by-place.pdf. Accessed 6 September 2014.

DUNEIER, M. (1999) Sidewalk. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

FITZPATRICK, S, Hawson, P, Bramley, G, and Wilcox, S. (2012) The homelessness monitor: Great Britain 2012. Crisis. http://www.crisis.org.uk/data/files/publications/ TheHomelessnessMonitor_GB_ExecutiveSummary.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2014.

FREIRE, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

FREIRE, P. (2005) Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, NY: Continuum.

GAUNTLETT, D. (2007) Creative Explorations: New Approaches to Identities and Audiences. London, UK: Routledge.

GLADWELL, M. (2006) Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking. London, UK: Penguin.

HALL, T, Lashua, B, and Coffey, A. (2008) Sound and the everyday in qualitative research, Qualitative Inquiry, 14(6): p.1019-40. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800407312054]

HALL, T. (2003) Better Times than This: Youth Homelessness in Britain. London, UK: Pluto Press.

HENLEY, J. (2014) The homelessness crisis in England: A perfect storm. The Guardian, 25 June. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jun/25/homelessness-crisis-england-perfect-storm. Accessed 3 July 2014.

HUTSON, S. (1999) Introduction, in Hutson, S and Clapham, D. (eds) Homelessness: Public Policies and Private Troubles. London, UK: Cassell, pp. 1-10.

HUTSON, S and Liddiard, M. (1994) Youth Homelessness: The Construction of a Social Issue. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

IGNATIEFF, M. (1999) The Warrior's Honor: Ethnic War and the Modern Conscience. London, UK: Vintage.

INGRAM, N. (2011) Within school and beyond the gate: The complexities of being educationally successful and working class, Sociology, 45(2): p.287-302. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038510394017]

JACOBS, K, Kemeny, J, and Manzi, T. (1999) The struggle to define homelessness: A constructivist approach, in Hutson, S and Clapham, D. (eds) Homelessness: Public Policies and Private Troubles. London, UK: Cassell, p.11-28.

JOHNSEN, S, May, J, and Cloke, P. (2008) Imag(in)ing 'homeless places': using auto-photography to (re)examine the geographies of homelessness, Area, 40(2): 194-207. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00801.x]

LEDWITH, M. (2001) Community work as critical pedagogy: Re-envisioning Freire and Gramsci. Community Development Journal, 36(3): p.171-82. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cdj/36.3.171]

LOMAX, H. (2012) Contested voices? Methodological tensions in creative visual research with children. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(2): p.105-17. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.649408]

MARCUSE, P. (1989) Gentrification, homelessness, and the work process: Housing markets and labour markets in the quartered city, Housing Studies, 4(3): p.211-20. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02673038908720660]

MAY, J, Cloke, P, and Johnsen, S. (2007) Alternative cartographies of homelessness: rendering visible British women's experiences of 'visible' homeless, Gender, Place and Culture, 14(2): p.121-40. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09663690701213677]

MCCARTHY, L. (2013a) Homelessness and identity: A critical review of the literature and theory. People, Place & Policy, 7(1): p.46-58. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.3351/ppp.0007.0001.0004]

MCCARTHY, L. (2013b) 'Re-visualizing the visual: Forging feminist informed participatory visual methodologies'. Presentation to the Royal Geographic Society conference, London.

MEAD, G.H. (1972) The Philosophy of the Act. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

PACKARD, J. (2008) "I'm gonna show you what it's really like out here": the power and limitations of participatory visual methods. Visual Studies, 23(1): p.63-77. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725860801908544]

PETTINGER, L, and Lyon, D. (2012) No way to make a living.net: Exploring the possibilities of the web for visual and sensory sociologies of work, Sociological Research Online, 17(2). http://www.socresonline.org.uk/17/2/18.html. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.5153/sro.2696]

PEW RESEARCH (n.d.) Question wording. Pew Research Centre for People & the Press. http://www.people-press.org/methodology/questionnaire-design/question-wording. Accessed 4 July 2014.

PIMLOTT-WILSON, H. (2012) Visualising children's participation in research: Lego Duplo, rainbows and clouds and moonboards. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(2): p.135-48. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.649410]

RADLEY, A, Chamberlain, K, Hodgetts, D, Stolle, O, and Groot, S. (2010) From means to occasion: walking in the life of homeless people. Visual Studies, 25(1): p.36-45. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14725861003606845]

RADLEY, A, Hodgetts, D, and Cullen, A. (2006) Fear, romance and transience in the lives of homeless women, Social & Cultural Geography, 7(3): p.437-61. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649360600715193]

RAVENHILL, M. (2008) The Culture of Homelessness. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

RAY, L. (2013) Photography and the public sphere. Discover Society, November 5. http://www.discoversociety.org/2013/11/05/628. Accessed 4 July 2014.

RICHARDSON, M. (1989) The artefact as abbreviated act: A social interpretation of material culture, in Hodder, I (Ed) The Meaning of Things: Material Culture and Symbolic Expression. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, p.172-7.

ROBINSON, Y and Gillies, V. (2012) Introduction: Developing creative methods with children and young people. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(2): p.87-9. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.649411]

ROSE, L. (1988) 'Rogues and Vagabonds': Vagrant Underworld in Britain 1815-1985. London, UK: Routledge.

ROSENTHAL, R. (2000) Imaging homelessness and homeless people: Visions and strategies within the movement(s), Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 9(2): p.111-26. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1009418301674]

SCHUMAN, H and Presser, S. (1981) Questions and Answers in Attitude Surveys: Experiments on Question Form, Wording, and Context. New York, NY: Academic Press.

SHILDRICK, T, MacDonald, R, Furlong, A, Roden, J, and Crow, R. (2012a) Are 'cultures of worklessness' passed down the generations? Joseph Rowntree Foundation, December 2012. http://wbg.org.uk/pdfs/worklessness-families-employment-full.pdf. Accessed 30 September 2014.

SHILDRICK, T, MacDonald, R, Webster, C, Garthwaite, K. (2012b) Poverty and Insecurity: Life in Low Pay, No Pay Britain. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781847429117.001.0001]

SMALL, D, and Verrochi, N. (2009) The face of need: Facial emotion expression on charity advertisements, Journal of Marketing Research, 46 (December): p.777-87. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.46.6.777]

SOMERVILLE, P. (1999) The making and unmaking of homelessness legislation, in Hutson, S and Clapham, D. (eds) Homelessness: Public Policies and Private Troubles. London, UK: Cassell, p.29-57.

SOMERVILLE, P. (2013) Understanding homelessness. Housing, Theory and Society, 30(4): p.384-415. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2012.756096]

SPENCER, S. (2010) Visual Methods in the Social Sciences: Awakening Visions. London, UK: Routledge.

ST MUNGO'S (2009) Down and out? The final report of St Mungo's call 4 evidence: Mental health and homelessness. http://www.mungosbroadway.org.uk/documents/1348/1348.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2014.

STEARMAN, K. (1998) Homelessness. Hove, UK: Wayland Publishers.

THAMES REACH (2010) Consultation on proposed changes to guidance on evaluating the extent of rough sleeping. London, UK: Thames Reach.

THOMAS, B. (2012) Homelessness kills: An analysis of the mortality of homeless people in early twenty-first century England. Crisis. http://www.crisis.org.uk/data/files/publications/Homelessness%20kills%20-%20full%20report.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2014.

THOMSON, P. (2008) Doing Visual Research with Children and Young People. London, UK: Routledge.

WILKINSON, I. (2013) The provocation of the humanitarian social imaginary. Visual Communication, 12(3): p.261-76. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1470357213483061]

WILLIAMS, M. (2010) Can we measure homelessness? A critical evaluation of 'Capture-Recapture', Methodological Research Online, 5(2): p.49-59.

ZUKIN, S. (1995) The Cultures of Cities. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell.