Geoff Payne and

Judy Roberts (2002) Opening and Closing the Gates:

Recent Developments in Male Social Mobility in

Britain

Sociological Research Online, vol.

6, no. 4,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/6/4/payne.html>

To cite articles published in Sociological Research Online, please reference the above information and include paragraph numbers if necessary

Received: 27/9/2001 Accepted: 25/2/2002 Published: 28/02/2002

Abstract

Abstract Introduction

Introductionthe mission of any second term must be this: to break down the barriers that hold people back, to create real upward social mobility, a society that is open (Blair 2001:2).

Mobility Traditions

Mobility Traditions

Data and Methods

Data and Methods

nationally-representative sample surveys of the British electorate, excluding Northern Ireland....The BES is the longest-running academic survey series in Britain..... conducted and coded in closely comparable ways (Heath and Payne, 2000: 257).

Male Mobility trends since the Nuffield Mobility Study

Male Mobility trends since the Nuffield Mobility Study

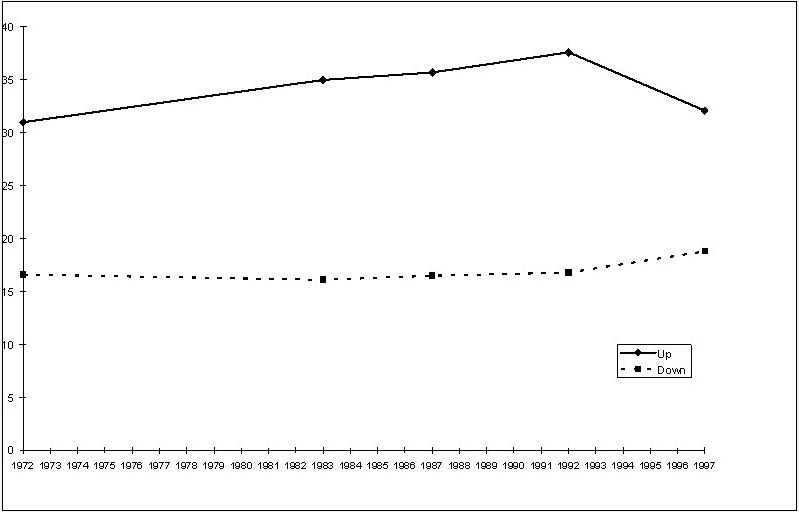

Fig 1: Male Overall Mobility 1972 – 1997(%)

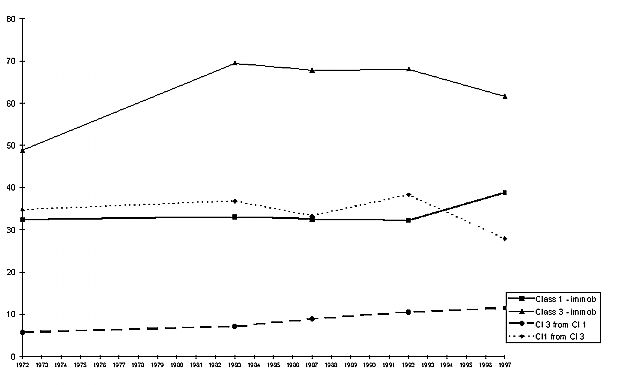

Fig 2: Male Mobility: Service and Manual Classes 1972 – 1997 (%)

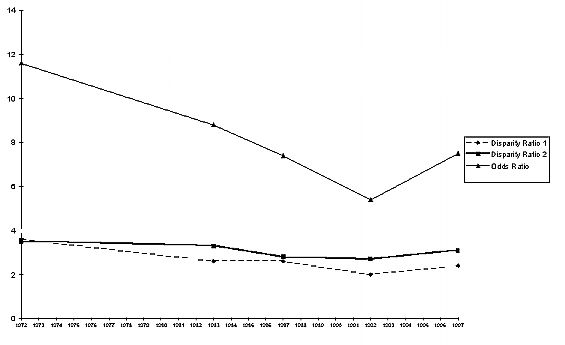

Fig 3: Male Comparative Mobility Coefficients 1972 – 1997

Interpreting Male Mobility Trends 1972-1992

Interpreting Male Mobility Trends 1972-1992

When we go on to consider relative mobility rates, and in this way abstract from the effects of this changing structural context, it is then the degree of stability rather than of change that is the more striking. Overall, in fact, a model of 'constant social fluidity' would seem to fit our data rather well …..Systematic shifts were evident in the pattern of absolute mobility rates, of a kind that would be expected from the nature of the changes occurring in the occupational structure. But relative mobility rates, which we take as our indicator of the degree of openness, remained generally unaltered: and the only trends that could arguably be discerned (apart from over the early stages of the life-cycle) were indeed ones that would point to a widening of differences in class chances (Goldthorpe 1987: 86, 328).

We may have mistaken changes in the shape of the class structure for changes in social fluidity or the degree of openness. In most advanced societies, the post-war years from the 1950s saw…..a growth of professional, managerial and administrative positions. This helped generate substantial rates of mobility (especially upward mobility) overall. But more 'room at the top' has not been accompanied by greater equality in the opportunities to get there….In sum, the growth of skilled white-collar work has increased opportunities for mobility generally, but the distribution of those opportunities across the classes has stayed the same (Marshall 1997: 5).

a marked tendency for all the odds-ratios in the later tables to be closer to unity than they were in the earlier tables. In other words, a rather weaker association between origins and destinations prevailed in Ireland in 1996 than in 1973 (Breen 2000: 403).

is at some variance with the conclusions reached by Goldthorpe et al. (1980) and Goldthorpe and Payne (1986) who had found that fluidity had remained constant across birth cohorts in Britain....(This) may simply reflect the different time periods covered. It is possible that, over the longer time-period available to us, there has been a real, albeit small, increase in the openness of British society that was not visible over the shorter time-period covered by Goldthorpe's work (Heath and Payne 2000, 273-5).

Male Mobility: the Period 1992-1997

Male Mobility: the Period 1992-1997

| Sons | Fathers | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 1972 | 26.4 | 25.4 | 48.2 | 14.5 | 28.5 | 57.0 | ||

| 1983 | 33.6 | 26.7 | 39.7 | 17.9 | 29.6 | 52.5 | ||

| 1987 | 34.8 | 26.3 | 38.9 | 18.7 | 31.4 | 50.0 | ||

| 1992 | 38.4 | 24.3 | 37.3 | 21.2 | 27.2 | 51.6 | ||

| 1997 | 36.4 | 28.9 | 34.6 | 23.6 | 35.0 | 41.4 |

Female Social Mobility

Female Social Mobility

| Daughters | Fathers | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 1983 | 17.6 | 49.8 | 32.6 | 20.1 | 27.8 | 52.1 | ||

| 1987 | 20.4 | 48.7 | 30.9 | 20.4 | 28.1 | 51.5 | ||

| 1992 | 26.5 | 46.8 | 26.7 | 23.2 | 28.7 | 48.2 | ||

| 1997 | 32.0 | 44.4 | 23.6 | 27.6 | 35.5 | 36.9 |

Some Concluding Observations

Some Concluding Observations

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

BLAIR, T (2001) The Government's Agenda for the Future. <http:www.pm.gov.uk/news.asp? News/d=1789§ionld=32>. BOTTOMORE, T. (1965) Classes in Modern Society. London: Allen & Unwin.

BREEN, R. (2000) 'Class Inequality and Social Mobility in Northern Ireland, 1973-1996', American Sociological Review, Vol. 65, No. 3, pp. 392-406.

BREEN, R. & ROTTMAN, D. (1995) Class Stratification. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

ERIKSON, R. & GOLDTHORPE, J. (1992) The Constant Flux. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

GIDDENS, A. (1973) The Class Structures of the Advanced Societies. London: Hutchinson.

GIDDENS, A. (1997) Sociology. (3rd. Edn.) Cambridge: Polity Press.

GOLDTHORPE, J. (1987) Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain. (2nd. edn.) Oxford: Clarendon Press.

HALSEY, A and WEBB, J. (Eds.) (2000) Twentieth-Century British Social Trends. Basingstoke: Macmillan. HEATH, A. (1981) Social Mobility. London: Fontana.

HEATH, A and PAYNE, C. (2000) 'Social Mobility' in Halsey and Webb, q.v.

IGANSKI, P., PAYNE, G. and ROBERTS, J. (2000) Social Exclusion and Structural Inclusion: the Socio-Economic Experience of Minority Ethnic Groups. Paper presented at the Cambridge Social Stratification Research Seminar, Clare College, Cambridge.

LEE, D. and TURNER, B. (1996) Conflicts about Class. London: Longman.

MARSHALL, G. (1997) Repositioning Class. London: Sage.

NOBLE, T. (2000) 'The mobility transition: Social Mobility trends in the First half of the Twenty-First Century', Sociology, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 35-52.

PARKIN, F. (1971) Class Inequality and Political Order. London: MacGibbon and Kee.

PATERSON, L. (2001) 'Education and Inequality in Britain'. Paper to the Social Policy Section, British Association for the Advancement of Science Annual Meeting: Glasgow.

PAWSON, R. (1993) 'Social Mobility' in Morgan, D. and Stanley, L. (eds) Debates in Sociology. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

PAYNE, G. (1987a) Employment and Opportunity. London: Macmillan.

PAYNE, G. (1987b) Mobility and Change in Modern Society. London: Macmillan.

PAYNE, G. (1999) Does Economic Development Modify Social Mobility? Paper presented to the British Sociological Association Annual Conference, Glasgow.

PAYNE, G. and ABBOTT, P. (Eds.) (1990) The Social Mobility of Women. London: Falmer.

ROBERTS, K. (2001) Class in Modern Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

ROSE, D. and O'REILLY, K. (1997) Constructing Classes: Towards a new Social Classification for the UK. Swindon: ERSC/ONS.

ROSE, D. and O'REILLY, K. (1998) The ESRC Review of Government Social Classifications. Swindon: ESRC/ONS.

RUNCIMAN, W. (1990) A Treatise on Social Theory. (Vol. 1) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SAUNDERS, P. (1996) Unequal But Fair. London: Institute for Economic Affairs.

SCOTT, J. (2000) 'Class and Stratification' in Payne, G. (Ed) Social Divisions. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

WESTERGAARD, J. and RESLER, H. (1975) Class in a Capitalist Society.London: Heinemann.