Stillbirth and Loss: Family Practices and Display

by Samantha Murphy and Hilary Thomas

The Open University; University of Hertfordshire

Sociological Research Online, 18 (1) 16

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/1/16.html>

10.5153/sro.2889

Received: 27 Feb 2012 Accepted: 17 Dec 2012 Published: 28 Feb 2013

Abstract

This paper explores how parents respond to their memories of their stillborn child over the years following their loss. When people die after living for several years or more, their family and friends have the residual traces of a life lived as a basis for an identity that may be remembered over a sustained period of time. For the parent of a stillborn child there is no such basis and the claim for a continuing social identity for their son or daughter is precarious. Drawing on interviews with the parents of 22 stillborn children, this paper explores the identity work performed by parents concerned to create a lasting and meaningful identity for their child and to include him or her in their families after death. The paper draws on Finch's (2007) concept of family display and Walter's (1999) thesis that links continue to exist between the living and the dead over a continued period. The paper argues that evidence from the experience of stillbirth suggests that there is scope for development for both theoretical frameworks.

Keywords: Stillbirth, Identity, Qualitative Research, Parenting

Introduction

1.1 Parents form pre-natal bonds during pregnancy (Sandelowski 1994). Though relatively rare, a stillbirth (the death of 'a child' born after 24 weeks' gestation (Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy 2001), occurs in several thousand pregnancies in the UK annually. For example, in 2009 the stillbirth rate for England and Wales was 5.2 deaths/1000 births (Office for National Statistics 2011); in Scotland, 5/1000 births (NHS Scotland 2011) and in Northern Ireland, 4.8 /1000 births (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency 2011). Drawing on interviews with parents bereaved by stillbirth, this paper examines what happens to that bond, by considering family practices after a stillbirth. It references Finch's work (2007) on display and Walter (1999) on continuing bonds with the dead.Theorising reproductive loss

2.1 While there is a large psychological literature on the experience of reproductive loss, the sociology of perinatal bereavement[1] remains under-developed since the early 1980s when studies in this area began to emerge. Sociological insight has suggested that couples may experience conflict following the loss of a child due to 'incongruent bonding' with him or her which gives rise to 'incongruent grieving' (Peppers & Knapp 1980): a male tendency to suppress emotions may result in their partner thinking that they are not grieving for the baby and, therefore, did not love it. Other research indicates that women often lack social support at times of reproductive loss (Rajan & Oakley 1993) and Malacrida (1999) has argued that the lack of societal recognition of perinatal loss is a cost to the economy in terms of unresolved grief, perhaps resulting in mental health problems later.2.2 Lovell (1997) has argued that, despite legal acknowledgement that a child has died, the stillborn occupies an ambiguous position because stillbirth, along with other forms of pregnancy loss, has tended '…to be devalued because there appears to be no person to grieve for' (p. 29). Lovell (1983) interviewed women who had experienced a late miscarriage[2] or stillbirth and identified that the mother who had suffered a stillbirth occupied an anomalous space on the maternity ward, being regarded as neither mother nor patient. The lack of a baby led bereaved mothers to see themselves as an 'embarrassment' to be discharged from hospital as soon as possible, whereas those mothers remaining in hospital felt 'out of place'. Furthermore, Lovell (1983) also noted that many hospital professionals assumed a 'hierarchy of sadness' in which miscarriages were regarded as lesser losses than stillbirths and stillbirths less important than neonatal deaths. She argued that this was unhelpful in understanding fully the experience of loss and that parental commitment to the pregnancy was a better indicator of the likely reaction to the death than the length of gestation.

2.3 Since Lovell's research, a growing literature on male grief has emerged. McCreight (2004) has explored male experiences of loss, highlighting how men may question their identity as fathers. Fathers reported that their partners, having been positioned as closer to the expected child than themselves, were seen by family, friends and health care professionals as more affected..by the loss: McCreight (2004) termed men subjected to such marginalisation of paternal grief as 'forgotten mourners'. There is now recognition of paternal experiences in self-help literature: fathers have begun to document their own experiences (see, for example, Di Clemente 2004; Don 2005).

2.4 Hospital protocols for perinatal loss now construct perinatal loss as bereavement: Davidson (2011) claims that the invention of the 'perinatal interval', the emergence of an academic literature on death, loss and attachment and the activism of pregnancy loss support groups that gave '…voice to women's grief' (2.4) are the primary reasons for the emergence of such protocols. UK Guidelines for Health Professionals (Schott et al., 2007) published by the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (Sands) recommend that parents be offered time with their baby: practices, where the body is seen by parents and often family and friends of the bereaved, provide visual evidence of the baby to a wider audience than previously. This has been subject to criticism: Hughes et al. (2002) claim that the more prolonged and closer contact between mother and stillborn baby, the greater the risk of mental health problems like depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Trulsson and Radestad (2004) say that trauma identified by Hughes et al. (2002) might not have been precipitated by seeing the baby but by the mismanagement of the care of parents during the time between the diagnosis of the death and the birth of the stillborn baby.

2.5 Drawing on interviews with the parents of 19 deceased children, some of which were stillborn, Cacciatore and Flint (2002) argue that rituals after the death of a child enable parents to retain a link with the stillborn. In the UK, collecting traces of the baby such as copies of footprints, handprints and locks of hair, to give to the parent(s) in a 'memory box', is now routine: a social identity for the baby, then, may be '…claimed [by parents] via material items and practices which promise or evoke embodiment' (Hockey & Draper 2005: 51). Many parents display photos of their dead baby at home, the images often include other family members. Layne (1992; 2000) suggests that the retention of material traces of the unborn child enables parents to legitimate their grief.

2.6 In cases where a first child dies, mothers and fathers have particular struggles with their identity (Murphy 2012) as the identity of parent is dependent on a relationship with a child. Thus, a mother can only be understood as such when thought of in relation to a dependent other: the baby or child (Jenkins 1996). While their social circle may have constructed them as putative parents, the death of the baby might negate their identity as parent, especially as all parents bereaved by stillbirth may at some point meet with silence. Rajan & Oakley (1993) note that friends and family of parents who have had a miscarriage or stillbirth often are unwilling to discuss the experience with the bereaved (see also Mander 2006). Layne (1997) argues that this cultural denial of loss is partly because '…unlike a growing child or an adult who leave behind a trail of existence, an unborn child lacks the material traces of social life' (p. 300) hence the move to retain traces of existence, potentially continuing the bond.

Continuing bonds thesis

3.1 The continuing bonds thesis, described as '…the dominant academic discourse' in the area of death studies by Valentine (2008: 4) may be applied to different types of bereavement. Its premise is that relationships are able to survive the life-death boundary which may occur through processes of negotiation and meaning-making (Valentine 2008; Martin 2010). Researchers noted survivors integrating the dead within their lives become agents in managing the deceased's biography (Walter 1999) and even the dying have some control over their post-death identities (Exley 1999). In On Bereavement, Walter (1999) distinguishes between private and public bonds with the dead. His conceptualisation of the private was individualistic: sensing the presence of the dead; talking to them; praying to or for them; associating them with symbolic places and things which enabled individuals to retain the deceased in their lives. Walter's public domain referred to post-death identities sustained through conversations with others who knew the deceased. This conceptualisation of the private and the public runs counter to the sociologically established divide between private and public spheres which conceptualises the former as the domestic sphere and the latter as the world of paid work.3.2 Continuing bonds with a deceased person entails work and is clearly more difficult for parents of a stillborn, although Cacciatore and Flint (2002) note the attempts of bereaved mothers and fathers. While Walter (1999) claims that, with regard to problematic deaths, the bereaved might reconstruct the deceased's biography, in stillbirth it seems that bereaved parents need to construct a biography for their stillborn (Howarth 2000) and, in doing this, retain the baby's place within the family.

Family practices and display

4.1 Building on Morgan's (1996) argument that there has been a shift from being a family to doing families, Finch (2007) introduced the concept of displaying families as integral to contemporary family practices. The family unit is formed by sets of activities rather than people: families are fluid, diverse and multi-faceted. Display is both internal – to other members of the family – and external, that is, to relevant audiences. Finch emphasised the social nature of the family and posed three key questions: why is display important; how is it done; and to whom do family relationships need to be displayed? Thus, the question of who is considered a family member rests on the relationships between possible members. Finch argued that '…for many people – the contours of 'my family' are not necessarily obvious or easy to identify' (p. 70) and hence display becomes an important or essential practice. Tools for display may be objects such as photos or domestic artefacts and/or narratives. Finch defined narratives as "stories through which people attempt to connect their own experiences, and their understanding of those experiences, to a more generalized pattern of social meanings about kinship" (2007: 78). People demonstrate that, for example, a former partner or step child is part of the family unit and, at times, display is more intensive than at others. Finch's concept of family display, combined with Walter's (1999) work, has the potential to throw light upon our understanding of the aftermath of stillbirth as parents seek to express the place, if any, that the stillborn has in their lives post-stillbirth.Methods

5.1 With few sociological studies on this subject and an underlying commitment to the '…belief that people create and maintain meaningful worlds' (Miller & Glassner 1997: 102), in-depth interviews were conducted. Parents were invited to first tell SM their story. As Finch (2007) states, people, through the use of narratives, connect their own experiences to a '…generalized pattern of social meanings about kinship' (p. 78). This was also a device to facilitate questioning later in the interview as the events that they narrated could be explored in more depth.5.2 Ethics approval for the project was granted by both a local NHS ethics committee and the University of Surrey Ethics Committee. Accordingly, all participants were given pseudonyms and potential identifiers, such as the name of their home town, the hospital where the stillbirth took place and names of family, friends and hospital staff, were removed at the transcription stage. Written, informed consent was obtained from interviewees and they were informed that they could end the interview at any time and did not have to answer all the questions. They were also offered rest breaks.

Sample characteristics

5.3 A total of 31 interviews were conducted with the parents of 22 stillborn babies, all singleton births. The study aimed to conduct a joint interview with both parents followed by individual interviews with each parent that would give parents a chance to give information that they may have been reluctant to in front of their partner. Joint interviews were held with ten couples of whom five women and four men also participated in individual interviews. A further 12 women were interviewed, their partners declining to participate in either joint or individual interviews. All interviews and their transcription were undertaken by SM. In the results section it is indicated which quotes are from separate, joint or follow-up interviews. The interviews took place in family homes and the length of joint interviews ranged from 45 minutes to four hours. The individual interviews ranged from ten minutes (a follow-up interview with a father) to three and a half hours.

5.4 Problems with recruiting fathers resulted in 12 women being interviewed individually. This is in common with previous researchers who had found bereaved mothers, but not fathers, to be pleased to take part in such research (Culberg 1971; Stringham et al. 1982; Rajan and Oakley 1993; Riches and Dawson 2000). Reasons for men's refusal to take part in the current study were not clear. It is possible that some men may have been reluctant to talk about their feelings (Puddifoot & Johnson, 1997) and that some women might have preferred their partners not to take part. Those mothers who were interviewed without their partners taking part were asked about their partners' behaviours which gave some additional insight into male behaviour albeit how that behaviour was interpreted by their partners. It is interesting to note that two of the men interviewed revealed that their partners had not given them a choice over participation. Costigan & Cox (2001) have suggested that non-participation of fathers may be connected to a variety of variables which included social class, with fathers in the manual classes being less likely to participate in family research.

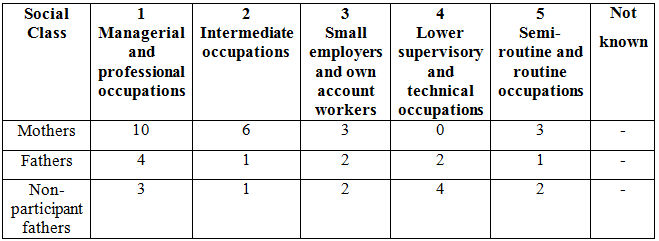

5.5 The table below shows the social class of the participants. Nineteen of the 22 mothers and seven of the ten fathers were from social classes 1-3 according to the NS-SEC classification. Fewer fathers from social classes 4 and 5 took part than from classes 1-3 But with such a small group it is difficult to assess whether this was a factor that impacted on paternal participation.

| Table 1. Social class of participants (NS-SEC) |

|

5.6 Most participants were white and British; one father was from the USA and two mothers were of south-Asian descent. Of the 22 stillborn children, 12 were the parents' first-born. The time since the loss ranged from six months to 12 years: for two parents it was under a year since the stillbirth occurred, seven parents were interviewed between one and two years post-death, five parents between two to three years of the loss and for eight parents the loss had happened more than three years before the interview. In some interviews a longer time frame was being reflected upon than in others and it is acknowledged that this has some impact on the data collected. As Finch (2007) noted, while individuals construct their social worlds, these constructions are fluid and an understanding of one's family will change over time and be rooted in individual biographies; the interviews recounted here reflect the understanding the individuals had of their family at the time of interview. However, Lundqvist et al. (2002) noted that research suggests that individuals' memories of birth experiences will remain consistent over a long period of time.

5.7 Parents were recruited through local Sands groups (four couples, six mothers), national support groups (including Sands) (five couples, five mothers) and personal contacts (one couple, one mother). Most participants were recruited via support groups such as Sands and other organisations that exist to support parents. This may have resulted in the parents interviewed having greater problems in adjusting to their loss than those who did not need to attend a support group, so the sample interviewed here may not be typical of bereaved parents. It is likely that parents would be practised in telling their story, which may have been repeatedly rehearsed.

Joint interviews

5.8 A particular strength apparent with regard to the ten joint interviews relates to the sensitivity of the interview and the emotions it might engender. Stillbirth is an especially sensitive subject and there was the possibility that parents might become upset while relating their story. This was borne out in the interviews and at times one partner or the other would become tearful and be unable to continue. In the joint interviews one partner could take up the story while the other composed him or herself and then continued. Interestingly, in none of the follow-up individual interviews with five women or five men or in the twelve individual interviews did respondents appear overly upset. Issues of dissent between the couples interviewed here were not often apparent, possibly because several couples belonged to support groups so an agreed version of the experience may have been reached some time previous to the interview: the 'public account'. Partners would be called upon to corroborate information, and disagreement only occasionally became apparent with regard to timing or order of events. Often, an agreement would be reached within the interview, which made explicit the socially constructed nature of the joint accounts.

Analysis

5.9 The analytical approach to the interview data was informed by grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin 1990). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in full by Samantha Murphy. As the later interviews took place, the first interviews were being analysed using the data software program Atlas-ti and from this early analysis initial concepts were generated that informed the later interviews. During the initial open coding, hundreds of concepts were isolated which were then grouped into categories. Once categories were isolated, using the process of axial coding, subcategories were created to explain them and, in this way, there emerged an understanding of how gender, as a macro-structure, impacts upon the experience of stillbirth.

Results

6.1 The themes presented here offer an insight into parental experiences of stillbirth and the work performed by parents with regard to the stillborn child. Mothers and fathers spoke of practices that reinforced the relationship they had with the stillborn over time. This section of the paper documents the way in which parents continue the bond and retain the stillborn as a family member. In doing so narratives and artefacts become tools for display of the stillborn as a member of the family. Finally, this section demonstrates how, despite these tools, there are barriers to including the stillborn in a continued family formation.Continuing the bond privately

6.2 Individualised experiences of bonds with the stillborn, which equated with Walter's (1999) private sphere, were recounted during the interviews. Examples of ways in which parents would do this included constructing an alternate biography for their son and daughter and the stage they would be at had they lived. Bridget, four years after the stillbirth of her fourth child, said:

Bridget: I was thinking I should be buying shoes for him, you know? And when the thing came up at church for the local parish school saying, you know applicants for the nursery school and I was thinking, you know, he would be old enough for me to apply for a nursery place now. [Follow-up interview]

6.3 Through constructing the alternate biography for the child, parents also re-construct their own. For mothers, particularly, stillbirth is an active loss; it is the loss of 'doing' parenting work with a child, making the activity of 'doing family' different to how it should have been. This applied to parents whether it was a first or subsequent child who died, In Bridget's case, she had lost the identity and the concomitant role of being mother to four living children.

6.4 Parents also recounted privatised bonds through sensing the presence of the dead, although only three parents referred to this. For example, one participant claimed to be psychic and to be in touch with her stillborn son:

Fiona: He's around, he's just, you know, we can't see him. [Joint interview]

6.5 While Bridget is constructing a biography for her son had he lived, it might be argued that Fiona is constructing a biography slightly differently – a continued existence but on a different spiritual plane. Although Fiona would conceptualise the stillborn's biography as taking place in a separate reality: she was adamant that at times her son returned momentarily and she talked of how she was watching him grow up.

Continuing the bond: narrative as display

6.6 There was a thread of experiences that referred to continuing bonds with the stillborn that went beyond parents' individualised worlds and which resonated with Finch's tools for display. Narratives were used by parents to create a biography for the child then shared with other family members. This led, in some cases, to siblings considering their own lost role and relationship with the stillborn. Ann, who lost her sixth child, reported that her children would often point to clothes in shops and remark on how the stillborn child would be wearing that size had she lived. Children, therefore, might assume an active role in the creation of the alternate biography or at least consider the impact an extra child might have had. Fiona, mentioned in the last section as believing that she had a psychic connection to her son, recounted how that presence impacted on the family three years post-death. Her partner also regularly referred to the child intervening in family matters. This enabled the stillborn to be integrated to some degree into their family. Moreover, they imputed character traits to him and he was constructed as a 'naughty boy' and duly told off for his behaviour, as unexplained phenomena were reinterpreted in terms of Fiona's beliefs:

Fred: We've had episodes on the computer 'cos you mentioned it before that he's always on the computer. Well you'd be typing and all of a sudden there'd be complete gobbledegook….We have a standing joke where we would say, now, stop mucking about [son]. [Joint interview]Whether Fred believed this or acted to support his wife's beliefs is unclear from the interview but such narratives were used by parents as a tool of internal family display and the stillborn would remain integrated in the family.

6.7 Talk might often centre on the surviving children's questions about the death. Maggie's family was a salient example of how the whole family was able to consider what life might have been like had their stillborn son, who would have been the eldest child, lived:

Maggie: They [subsequent children] do say, 'There should be five of us Mummy, where are they all?' My little one said, 'We'd had to have needed a big van.' …[My youngest daughter said] 'How many people will sit at a dinner table? You'd have to cook twice.' [Separate interview]

6.8 Through talking about the stillborn, both children and parents were able to position themselves in relation to a person with some type of identity albeit without a body. For Maggie and her family this was only accomplished many years after the loss. For over a decade the stillbirth was never referred to. The inclusion of the stillborn after so long was precipitated by Maggie's hysterectomy. Not being able to have more children led her to reconsider the constituent members of her family. The fact that the bond with the stillborn was able to be re-established after a decade suggests strongly that the mother had always retained a private bond with her eldest son. In each of these instances, families displayed relationships with the stillborn whose absence was 'felt', even in cases where some family members had not been born when the stillbirth happened.

6.9 It was not only toward the family that such practices of display were directed. The question 'how many children do you have?' posed by persons they might meet, would also give parents a chance to acknowledge the stillborn in the public sphere. For example,

SM: When people ask you, how many children you have, what, what do you say?

Ann: I always say it [six]

SM: You always say it.

Ann: Yeah, yeah. 'cos actually somebody who started in the school asked me in the school. She said "Ooh, someone said you had [son], [eldest daughter] and then three little ones." I said, "Yeah, and then the baby I lost," and they're like "Oh" because to me she is part of my family [emphasis added]. [Follow-up interview]

6.10 Recounting the experience to other people was a further way in which the stillborn would be remembered as a son or a daughter. As Rebecca, whose husband would not talk about their son, explained:

Rebecca: I talked to friends a lot. I bored everybody absolutely rigid. I just talked and talked and talked and talked and talked and talked about it to anybody who'd listen to me because that was all I had left if you know what I mean? Talking about it and talking about what had happened was all I'd got. [Separate interview]

6.11 Rebecca had lost her first child and here she is reporting what happened at the time of loss. Interviewed 12 years later, she only mentioned her first child if directly asked about him. There is no grave, no photo and no memorial. For Rebecca display is far less important than it used to be and this changed once she had given birth to a living child and the proof of her motherhood could be demonstrated publicly. The intensity of Rebecca's need to display her relationship with her stillborn son through narrative, dissipated over time.

6.12 Memorial services were a way in which a joint narrative that included many stillborn children (as well as those who died shortly after birth) may be recognized. For those men, reluctant possibly to talk about the loss, attendance at such events might be seen as a way they could tacitly acknowledge their relationship to a stillborn baby:

SM: Did [husband] go to the Sands meetings with you?

Una: Doesn't do anything, no. The only things he'd come to are like fun days or balloon releases. Doesn't, no; won't talk about it. That's how he deals with it. I'll talk till kingdom come about my son. [Separate interview]

6.13 A further narrative about the stillborn involved speaking to health professionals, most often midwives, as parents sought to improve practice around perinatal loss. Several participants availed themselves of the opportunity to tell their story so that medical professionals might begin to understand how stillbirth affects a mother and family. The following excerpt demonstrates this. Una considered that staff needed to hear about the lived experience:

SM: Because you've got the guidelines for health professionals…

Una: But then they're not real. Whoever wrote them hasn't got an understanding, because we gave the talk to the midwives and I made them cry when I told them what I told the girls [her two daughters], and I actually apologised and I said, "I didn't mean to upset you." "But Una" [they said] "we needed to know how important that [memory] book was, to us it's a book that we just put in the hand and footprints we didn't know it could be a bloody story book to two little girls." [Separate interview]

6.14 In talking to the health professionals, Una publicly engaged in identity work by telling the story of the stillbirth and its aftermath to the midwives. This is a point at which her display of identity work becomes more intense as she lays claim to the identity of mother of a stillborn. This excerpt from the interview also demonstrates how artefacts, that is, the memory book that contained the handprints and footprints of the stillborn, was used by Una to support her narrative.

6.15 Ann used her story to attempt to change practice. Bleeding profusely and in great pain, she had waited for hours to be seen in her local A&E department. Through the use of her narrative of loss, she demanded that women who had been in her predicament would not be kept waiting in the way she was:

Ann: All I actually asked them for and I actually, my GP actually put it in writing the same sort of thing, was that if anybody with any signs of pre-eclampsia and that had been in and out of for the last week like I had been monitored that closely, don't leave them sort of waiting around; get them straight up there so it doesn't happen again. [Joint interview]

6.16 The reason many parents decided to take part in this research was also altruistic – to help improve practice. Sheila summarized this attitude:

Sheila: I know that I have to go through stuff [like this interview] because I think it's a job that we have to do in a sense to make it real to other people and to widen the understanding of stillbirth. [Separate interview]As Finch indicated, the display of family practices may be more intense than at others. At points when parents tried to educate practitioners and facilitate change were times when display of the stillborn became more intense.

Continuing the bond: artefacts as display

6.17 Physical objects were also tools for display for parents and these took many different forms. The most usual were photos that were either on public display or kept in a more private place such as a bedroom. Only three parents did not have a photo. Sheila, for example, had the photo on the mantelpiece and reported that:

Sheila: you know, [elder sister of stillborn daughter], she'll pray for her every night and she would sometimes walk by the photo and give her a kiss, the photo on the mantelpiece. [Separate interview]

6.18 Ornaments which represented the stillborn had an important place in the homes of other interviewees too:

Ann: She's got little bits at Christmas, little china shoes that go on there and I mean they [the children] love her, light their candles, play with her bits. [Follow-up interview]

6.19 Functional items served as memorials in some families, for example, a bench in the garden:

Carl: We've also got a tree planted here as well. A little tree, we've been a few times and we're also getting a bench for the garden as well, so it's sort of a permanent reminder here. [Follow-up interview]

6.20 Occasionally, surviving children who might not have learned any inhibitions about talking about death, would initiate talk of the stillborn. In the following two examples, photos were shown publicly:

Isobel: He's [son] shown the checkout lady at Safeway's a picture of [daughter], whipped it out of my purse and said, 'No I haven't just got a brother I've got a sister as well.' [Joint interview]Ann: I got a phone call when I was at home and [the headteacher] said 'Look [daughter's] brought these pictures in.' She'd taken them out of [the memory] box and I didn't even know. 'She wants me to see them and the teachers,' she said, 'and the children.' [Joint interview]

6.21 It is apparent from these two incidents that some children are keen to remember and acknowledge their lost sibling as well as the parents. This might not be limited to siblings who were old enough to understand and have a lasting remembrance of the death but also extended to younger children who were born after the stillborn, as demonstrated by Maggie's experience.

6.22 Graves were also public reminders of the loss:

SM: Do you go [to the grave] a lot?

Una: In the summer we went for a couple of picnics down there with the girls because it's under a tree. We went and cleaned him all up and we went with another family we know through Sands and together we all cleaned the stones and everything, polished it all up, we did everything. [Separate interview]

6.23 The cleaning of the grave was highly symbolic as a tidy, cared-for, well-visited grave of a stillborn shows other people that this is a child whose memory is very much alive. The grave was important for some parents, as Ian said when referring to their daughter's headstone:

Ian

: We wanted [daughter] to be recognised.

6.24 His partner, Isobel reinforced the point:

Isobel: we wanted a headstone up as soon as possible just so to see her name. She's you know, there. And we went and got the certificate. We've got you know, a birth certificate to prove that she was here you know. That's the main sort of thing, the recognition, they are still here, they are still part of us and things like that…..we had people at the playgroup, which is still attached to the school he goes to now, they've planted a tree for her and put in a little plaque with her name on it with a little butterfly. [Joint interview]

6.25 Continued display of the child as an individual who had lived was important for Ian and Isobel and others, too, were keen to try and include the stillborn in family life. Amy and her husband had paid for a bench with a name plaque that would provide a private space for the parents to continue to include their stillborn son:

SM: So have you planted a tree or done anything like that?

Amy: No, actually we're getting a memorial bench at the nature reserve because that was always a place that we were going to take him, feed the ducks and that. In fact, we've been down there loads since and whenever we feed the ducks I do it with a smile on my face, um, and so we decided that we would get a memorial bench down there because when, once this new baby's born, we can all go there as a family and [son] will still be included. [Separate interview]

6.26 Parents would use other physical objects in order to remind them of the stillborn and these might not necessarily alert others to the bereavement. For example, at an interview with one couple, I [SM] made reference to the large decorative butterflies that adorned their house. The butterfly was, for them and their son, a symbol of their stillborn daughter and, as such, those adornments served as a daily reminder: for this whole family, the stillborn was remaining a continuing feature in their lives:

Isobel: She's with us, definitely. [Our son] says 'she's in my heart and in my head'. [Joint interview]

6.27 For George and Grace the item was a mug: they were acutely aware that their social circle did not consider them to be parents and Grace painted a mug for her husband on the first Father's Day following the loss. This served as a reminder of her husband's identity as father to the stillborn:

SM: Do you think other people saw you as Mum and Dad? George: Not really, well, I wouldn't say so, really ….

Grace: I painted a mug for you, didn't I on Father's Day? And, you know, one of those, you know, paint a mug but instead of doing it on the thing I wrote on the bottom so not everybody would have to see it. Um, but it was sort of, you know, I think I just wrote Happy Father's Day. [Joint interview]

6.28 Everyday items, therefore, were explicit reminders of the stillborn for the family and served as internal family display in the domestic sphere. However, they also had the potential for a public display of the stillborn if someone chose to comment on them. In a world where talking about death can be challenging, these symbols may be seen as a way of implicitly subverting societal taboos around loss and death.

Barriers to display

6.29 While Walter's might argue that the continuation of the bonds with the stillborn such as the ones above would be public, it was also clear that parents who included the stillborn in their family may not necessarily do so beyond the domestic sphere. It would be wrong, therefore, to assume that there were no barriers to displaying the stillborn. This might even include displaying the baby within the domestic sphere. For example, less than a year after their loss, Christina's husband was vehemently opposed to having a photograph of their daughter on display so she resorted to keeping one in a drawer upstairs:

Christina: But yeah, he's always right uncomfortable talking about it. He's even got nasty sometimes, 'I don't want to talk about it.' If I try to talk about it, 'I don't want to talk about a reason, she's dead, she's gone, she were my daughter, I miss her but I don't want to talk about her.' He doesn't, we haven't got any photos up. [Separate interview]While the photo might be a tool for display and continuing a bond for one parent, for another it might make for discomfort and give rise to conflict between couples.

6.30 Una was one mother who was publicly silenced on the subject:

Una: When I was pregnant with [daughter who was born after the stillbirth] they wouldn't let me go back to antenatal classes….They told me, they said, 'Una, we'd like you to come, but we daren't.' I said 'Why?' They said 'If somebody says something you're just gonna jump down their throats aren't you?' I went, 'Yeah. I can hear it now, and the people going, I'm not looking forward to giving birth, the pain, I say I can't wait for the pain then at least I know there's something coming, and then I can say, just get that head out and I say as long as it's crying.' [Separate interview]Other parents like George and Grace would respond to signs from their friends that the time for talking of the stillborn had passed: for example, in the noticing of stifled yawns and rolling their eyes.

6.31 Parents would also self-regulate display, especially in response to the particularly difficult question of how many children they had. This would pose a quandary for them: how many children did they have? Should the stillborn be included?

SM: When people ask you how many children you have, what do you tell them?

Christina: Oh, that's a right hard one. Um, if people say, mm, it depends where I am and I've struggled with this. It depends where I am and what I want to say and now I don't feel so bad because I'd decided if I don't tell them about [daughter] then that's my choice. [Separate interview]

6.32 Many parents would talk of weighing up the situation before answering but the denial of the child was problematic for some parents as it would lead them to feel guilty as if by not acknowledging the child they were denying the stillborn its identity as their son or daughter, but others would consider 'denial' to be a practical tool to ensure that social situations ran smoothly. George, by dint of much thought, had found a way round this:

George: I've got two lovely children with me is my 'out clause' because that doesn't necessarily alarm-bell them that I had another so I've learnt to, to build my phrase, you know. [Joint interview]By consciously 'building' this phrase, George did not feel that he was actively denying the existence of his first-born son – he had two children with him, but another child was not with him. It is a subtle reference to the loss but not one that will prompt questioning.

Discussion

7.1 Walter has argued that, following the death of an individual, bonds are not severed with the deceased but continue for many years afterward. The accounts presented here demonstrate that, despite not living outside the womb, bonds continue with the stillborn, too. These accounts support the claims made by Howarth (2000), Hockey & Draper (2005) and Layne (1997) that the material traces left following a stillbirth are important for parents to claim their child's identity; those traces also enable them to continue a bond with the stillborn. Walter argues that there are two spheres within which these bonds may continue: the private and the public. However, while he conceptualises the private sphere as the realm of the individual and the public as everything beyond this, the data here suggests that the spheres within which parents are able to continue a bond with the stillborn may be separated into three overlapping spheres. First is the private sphere, which is akin to Walter's (1999) understanding of this term. For the parents in this study, there was some evidence of highly individualistic and privatised bonds. Second, is the domestic sphere, which may include memorabilia and discussion of the stillborn within the family. The third sphere, the public, is where practices of display will be towards people other than family members. These practices may include activities such as attendance at memorial services, talks to medical professionals or showing the photo to other people. The behaviour of mothers and fathers might cut across all three spheres and will change over time. A photo in someone's home might be a private reminder but it becomes more public when others are invited into the home and the stillborn is 'displayed'. Parents might talk about the stillborn with each other but they might not necessarily do so in a more public place unless they were tasked with raising awareness of stillbirth. The analysis of the accounts generated for this study, therefore, suggests that a more nuanced approach is needed when studying accounts of bereavement and continuing bonds and merits further investigation with forms of death other than stillbirth.7.2 Finch has argued that the question, 'who constitutes my family' is a question about relationships. In the aftermath of a stillbirth, parents may find it difficult to position themselves as being parents albeit not to a live child, however, if they are to continue the bond with the stillborn in a way that moves beyond the individualised private bonds, then they are beginning to display the stillborn, either to their family or in a wider public arena. Through the use of tools for family display, the stillborn may be included as a member of the family over a continued period of time. In common with Almack (2011), we found Finch's (2007) argument that there are degrees of intensity to be useful and parents of stillborn babies may choose or reject that identity at particular times after the loss. For instance, Rebecca chose to talk about the stillborn with friends after the event as that helped make it more real for her. As her life changed with the birth of another child, the need for displaying the stillborn child as a part of the family receded: proof of her parenthood was resident in her newborn daughter.

7.3 Why is display important for parents of a stillborn? The inclusion of the dead child in their family allows them to acknowledge the embodied relationship that they had with their child during pregnancy and for a short period following the stillbirth. Continuing a bond with the stillborn child, therefore, may reinforce for bereaved parents their sense of being a mother and father. Another reason of the importance of display was in the use of narrative for raising awareness of the effect of loss among health professionals and in changing practice in the future.

7.4 Both narrative about the stillborn and artefacts were used to display the stillborn as a member of the family and, as such, retain a bond to a greater or lesser extent. Narrative might be used, either internally (as Bridget recounted) or externally, in a number of ways: through constructing a biography for the dead child and, therefore, for themselves; through the telling of the story of the stillbirth to other people; or by taking part in a joint narrative such as a memorial service. The photos and domestic objects that Finch (2007) refers to as her second type of 'tools for display' were also apparent in the accounts. While there were few of these for parents to use, photos of the baby – either ultrasound pictures or those taken after birth are clearly important. In the absence of physical artefacts, symbolic reminders of the baby might also become important, for example, decorated mugs and butterflies displayed on the house. The continued presence of such objects in or around the house serves to remind all members of the family of the relationship with the stillborn and his or her place in the family.

7.5 These ways of continuing a bond with the stillborn suggest that the identity of 'bereaved parent' is one that is active, on-going and requires identity work: families actively demonstrate that one member did not survive birth. Howarth (2000) has noted how parents construct biographies for a stillborn child and the experiences of the participants in the current study support her claim, but this study also suggests that the biographies of the stillborn are, in addition, constructed by his or her siblings[3].

7.6 It is not possible from this study to make generalisations about practices over a sustained period of time, as some parents were interviewed within months of the loss while others were interviewed years after it occurred. The accounts suggest that, for some interviewees, bereaved parenthood continues to be an important aspect of their identity for many years and that the practices around the stillbirth are not always fully developed within a short period of time after the stillbirth. However, they also suggest that narratives and artefacts are conduits for each other. A remark regarding butterflies on a person's house may enable a narrative about a child. Talking about the stillborn with people outside the family may involve the production of evidence as in the case of Una, who showed medical professionals a memory box.

7.7 In answering Finch's third question, to whom is it important to display the family, we can begin to understand why display is more important in some cases than in others and thus emphasise the fluidity of families. For those parents, for example, who lose their first baby, and whose identity might be open to question, display may be about reinforcing to others their own identity of mother and father.

7.8 Finch's (2007) concept of display gives additional analytical purchase here. Almack (2011) has noted that the concept of displaying families may be extended. She questioned the '…extent to which external audiences….are involved in acknowledging and establishing family-like relationships, which raises points about the interactive and multi-layered nature of display work' (p. 117). The accounts presented here demonstrate that it is not always possible or desirable to display the stillborn as part of the family, therefore, we would suggest that there is a fourth question to add to Finch's three questions regarding family display: what barriers are there to displaying families? In displaying the stillborn, many parents experienced conflict either with each other or with other people, whether this was from raised eyebrows, visible boredom or self-regulation as they decided not to acknowledge the stillborn as a member of their family. When this conflict occurred between couples, we might term these incongruent family practices. While Peppers & Knapp (1980) argued that it was incongruent bonding that gave rise to incongruent grieving that cause couple conflict following a child's death, several of the accounts here suggested that incongruent display of the stillborn was a cause of conflict.

7.9 As Finch noted, family practices change over time. Since the interviews for this study took place, the bond with the stillborn may have changed depending on the course of family life since the death. The analysis demonstrates that family practices of display may perhaps be more complex than Finch suggests: there are barriers and resistance to display for families that do not conform to social expectations. We suggest that families in other socially awkward circumstances may be subject to such resistance. Such families may be those that regularly include deceased members whether children or adults or those that include a member who is absent for a stigmatising reason, either voluntarily or involuntarily. What barriers exist to including such members in the family is something that invites further investigation.

Notes

1Perinatal loss is defined as a loss of a baby either by stillbirth or within the first seven days of life (ONS 2011).2The definition of late miscarriage varies but will normally be a loss that occurs between 12 and 24 weeks' completed pregnancy (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2002).

3This research project was prompted by the personal experience of Samantha Murphy who had a stillbirth in 1994. Some years afterwards her own daughter admitted to making a character on the popular computer game The Sims that was named after her dead sister.

References

ALMACK, K. (2011) 'Display work: lesbian parent couples and their families of origin negotiating new kin relationships' in Seymour, J. and Dermott, E. (eds) Displaying Families: A New Concept for the Sociology of Family Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

CACCIATORE, J. and Flint, M. (2012) 'Mediating grief: post-mortem ritualization after child death', Journal of Loss and Trauma, vol. 17, p. 158-172. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.595299]

CONFIDENTIAL ENQUIRY INTO STILLBIRTHS AND DEATHS IN INFANCY (2001) 8th Annual Report. London: Maternal and Child Health Consortium.

COSTIGAN, C. L. and Cox, M. J. (2001) 'Fathers' participation in family research: Is there a self-selection bias?' Journal of Family Psychology, Vol 15, Issue 4, p. 706-720.

DAVIDSON, D (2011) 'Reflections on Doing Research Grounded in My Experience of Perinatal Loss: From Auto/biography to Autoethnography', Sociological Research Online Vol. 16, Issue 1: <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/16/1/6.html>.

DI CLEMENTE, M (2004) Living with Leo, Bosun-Publications.

DON, A (2005) Fathers Feel Too: a Book for Men by Men on Coping with the Death of a Baby, Bosun-Publications.

EXLEY, C (1999) <'Testaments and memories: negotiating after death-identities'>, Mortality, Vol. 4, No. 3, p.226-249.

FINCH, J. (2007) 'Displaying families', Sociology, vol. 41, No 1, p. 65-81. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038507072284]

HOCKEY, J and Draper, J (2005) 'Beyond the womb and the tomb: Identity, (dis)embodiment and the life course', Body and Society Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 41-57. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1357034X05052461]

HOWARTH, G (2000) 'Dismantling the boundaries between life and death', Mortality Vol. 5, No. 2, p. 127-138. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713685998]

HUGHES, P, Turton, P, Hopper, E, & Evans, C D H (2002) 'Assessment of guidelines for good practice in psychosocial care of mothers after stillbirth: A cohort study', The Lancet, Vol. 360, No. 9327, p.114-118. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09410-2]

JENKINS, R (1996) Social identity. London: Routledge.

LAYNE, L L (1992) 'Of fetuses and angels: Fragmentation and integration in narratives of pregnancy loss', Knowledge and Society: The Anthropology of Science and Technology Vol. 9, p. 29-58.

LAYNE, L L (1997) 'Breaking the silence: An agenda for a feminist discourse of pregnancy loss', Feminist Studies, Vol. 23, No. 2, p. 289-315. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3178398]

LAYNE, L L (2000) '"He was a real baby with real things": A material culture analysis of personhood, parenthood and pregnancy loss', Journal of Material Culture, Vol.5, No. 3, p. 321-345. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/135918350000500304]

LOVELL, A (1983) 'Some questions of identity: Late miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal loss', Social Science and Medicine Vol. 17, No.11, p. 755-61. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(83)90264-2]

LOVELL, A (1997) 'Death at the beginning of life' in Field D, Hockey, J and Small N (Eds.) Death, Gender and Ethnicity, London: Routledge.

LUNDQVIST, A., Nilston, T. and Dykes, A.-K. (2002) 'Both empowered and powerless: Mothers experience of professional care when their newborn dies', Birth, 29 (3) p. 192-199. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00187.x]

MANDER, R (2006) Loss and Bereavement in Childbearing. Abingdon: Routledge.

MALACRIDA, C (1999) 'Complicating mourning: The social economy of perinatal death', Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 9, No. 4, p. 504-519. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104973299129122036]

MARTIN, D D (2010) 'Identity management of the dead: Contests in the construction of murdered children', Symbolic Interation, Vol. 33, No. 1, p. 18-40. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1525/si.2010.33.1.18]

MCCREIGHT, B S (2004) 'A grief ignored: Narratives of pregnancy loss from a male perspective', Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 26, No. 3, p. 326-350. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00393.x]

MILLER, J, and Glassner, B (1997) The 'inside' and the 'outside': Finding realities in interviews in Silverman, D (Ed.) Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice, London: Sage.

MORGAN, D. H. J. (1996) Family Connections. Cambridge: Polity Press.

NHS SCOTLAND (2011) Scottish perinatal and infant mortality and morbidity report 2009. Edinburgh: Common Services Agency/Crown Copyright.

OFFICE FOR NATIONAL STATISTICS (2011) Childhood, Infant and Perinatal Mortality in England and Wales, 2009. Newport: ONS. Accessed online at: <http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/child-mortality-statistics--childhood--infant-and-perinatal/2009/index.html>.

NORTHERN IRELAND STATISTICS AND RESEARCH AGENCY (2011) Statistics Press Notice: Deaths in Northern Ireland (2009). Accessed online at: <http://www.nisra.gov.uk/archive/demography/publications/births_deaths/deaths_2009.pdf>.

PEPPERS, L G, and Knapp, R J (1980) Motherhood and mourning. New York: Praeger.

RAJAN, L and Oakley, A (1993) 'No pills for heartache: The importance of social support for women who suffer pregnancy loss', Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 75-87. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02646839308403198]

ROYAL COLLEGE OF OBSTETRICIANS AND GYNAECOLOGISTS (2012) Information for You: Recurrent and late miscarriage: tests andtreatment of couples. Accessed online at: <http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/Recurrent%20and%20Late%20Miscarriage_0.pdf>.

SANDELOWSKI, M (1994) 'Separate, but less unequal: fetal ultasonogaphy and the transformation of expectant motherhood/fatherhood', Gender and Society, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 23-245. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089124394008002006]

SANDS (2012) Preventing Babies Deaths: What Needs to be Done, London: Sands.

SCHOTT, J, Henley A and Kohner, N (2007) Pregnancy loss and the death of a baby: Guidelines for health professionals. London: Sands.

STRAUSS, A, and Corbin, J (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

TRULSSON, O. and RADESTAD, I. (2004) 'The silent child – mothers' experiences before, during, and after stillbirth', Birth, 31 (3) p. 189-195. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00304.x]

VALENTINE, C (2008) Bereavement Narratives: Continuing Bonds in the Twenty-first Century. London: Routledge.

WALTER, T (1999) On bereavement: The culture of grief. Maidenhead: Open University Press.