Motherhood, Medicine & Markets: The Changing Cultural Politics of Postnatal Care Provision

by Maria Zadoroznyj, Cecilia Benoit and Sarah Berry

The University of Queensland; University of Victoria; McGill University

Sociological Research Online, 17 (3) 24

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/17/3/24.html>

10.5153/sro.2701

Received: 9 Jan 2012 Accepted: 11 Jun 2012 Published: 31 Aug 2012

Abstract

In high-income countries welfare states play a crucial role in defining - and re-defining - what is offered as publicly provided care, and as a result shape the role of families, markets and the voluntary sector in care provision. Fiscal policies of cost containment, coupled with neoliberal policies stressing individual responsibility and reliance on market forces in recent decades, have resulted in the contraction of state provided care services in a range of sectors and states. There has also been widespread retrenchment in public health sectors across many countries resulting in policies of deinstitionalisation and early discharge from hospital that are predicated on the assumption that the family or voluntary sector will pick up the slack in the care chain. At the same time that this loosening of medicalized control has occurred, services to families with young children have become increasingly targeted on 'at risk' mothers through widespread population surveillance. To date, analyses of the implications of these important changes in care provision have primarily focused on health services and outcomes for birthing women and their newborns. In this paper, we make the case that post-birth care is a form of social care shaped not only by welfare state policies but also by cultural norms, and we suggest an analytic framework for examining some of the recent changes in the provision of postpartum care. We use examples from three developed welfare states - the Netherlands, Australia and Canada - to illustrate how variations in welfare state policy and cultural norms and ideals shape the provision of home and community based postnatal services.

Keywords: Post-Birth Care, Welfare States, Markets, Familialism, Surveillance, Netherlands, Australia, Canada

Introduction

1.1 The centrality of the welfare state to understanding the provision of social care has long been recognized (Daly & Lewis 2000; Daly & Rake 2003; Leitner 2003; Ungerson & Yeandle 2007). Welfare states play a crucial role in defining – and re-defining - what is offered as publicly provided care in high-income countries, and as a result shape the role of families, markets and the voluntary sector in care provision (Benoit & Hallgrimsdottir 2001)). The dynamic and variable responses of welfare states to ideological forces brought on by economic pressures - from the 1970s oil price shocks to the current global financial pressures and neoliberal policies to limit government expenditures and reduce deficits - have all been implicated in analyses of the possible retrenchment of benefits and care services across many sectors of the welfare state (Greve 2011; Saunders & Deeming 2011; Warner & Gradus 2011). There has also been widespread retrenchment in public health sectors across many countries (Eberhard-Gran 2010; Declercq et al. 2008; Goulet, D'Amour & Pineault 2007; Elattar et al. 2008; Cargill et al. 2007). At the same time, that this loosening of medicalized control has occurred, services to families with young children have become increasingly targeted on 'at risk' mothers through widespread population (Zadoroznyj, 2006).1.2 In this paper, we investigate this contradictory situation by examining changes in the provision of care to mothers in the post-birth period. We make the case that post-birth care is a form of social care shaped not only by welfare state policies but also by cultural norms (Hochschild 1995; Daly & Lewis 2000; Fox 2009). We propose an analytic framework for understanding post birth care in the home and community in terms of welfare state policies and cultural norms and ideals. We illustrate the utility of this approach through the examination of some aspects of postnatal care provision in three welfare states: Australia, Canada and the Netherlands. All of these countries have universal health care systems, relatively safe and effective systems of maternity care provision, and family-oriented policies that promote healthy child development. Yet the actual arrangements of post-birth care vary significantly across each of these welfare states. In our conclusion we present some implications of such cultural variation for new mothers and their children.

Social care and the welfare state

2.1 The provision of care – both public and private - takes place within particular social and political economies, and is embedded in normative frameworks of obligation and responsibility (Daly & Lewis 2000: 284-5). Cultural norms and the role of the state are central in shaping assumptions about whether the need for care exists, as well as in determining how care is perceived, how care work is provided, and how care is financed (Hochschild 1995; Kremer, 2006; 2007). The role of the state is so crucial precisely because care is'an activity with costs, both financial and emotional, which extend across public/private boundaries. The important analytic questions that arise in this regard centre upon how the costs involved are shared, among individuals, families and within society at large." (Daly & Lewis 2000: 285).

2.2 Daly & Lewis (2000) developed a definition of social care which builds on the assumption of a mutually-constitutive relationship between social care and the welfare state. They argue that "care as an activity is shaped by and in turn shapes social, economic and political processes" and, consequently, that social care is both "an activity and a set of relations lying at the intersection of state, market and family (and voluntary sector) relations" (Daly & Lewis 2000:295).

2.3 This conceptualization of social care enhances welfare state analysis by shifting the focus from specific policy domains to the distribution of care among sectors and across shifting, evolving boundaries (Daly & Lewis 2000:295). Furthermore, this approach offers the capacity to capture trajectories of change in and across welfare states (Daly & Lewis 2000:291). Much of the recent literature on the provision of care and care work analyses their gendered and globalised provision (Glucksmann & Lyon 2006; Zimmerman, Litt & Bose 2006; Boddy et al. 2006; Ehrenreich & Hochschild 2003). However, the care of new parents has received little sustained attention in this literature (Oakley 1992; Hochschild 1995), even though the period after birth is a period of transition for mothers, and to a lesser extent fathers (Fox 2009), that brings 'into stark relief questions about the giving and receiving of care' (Fink 2004: 3). How this care is organised is historically and culturally variable, and reflects state policy and cultural norms. Questions such as who will provide care, whether it will be formal or informal, where it will be spatially located, its duration, and how it will be paid for, are as relevant to the postpartum period as they are to other situations where care is needed, including illness, older age, early childhood, and disability. Also open to debate is who is at fault when care is deemed inadequate, especially in regard to children who are seen as highly vulnerable and potentially "at risk" to abuse and neglect (Willms 2002).

2.4 Fiscal policies of cost containment, coupled with neoliberal policies stressing individual responsibility and reliance on market forces, have resulted in the contraction of state provided care services in a range of sectors and states (Warner & Gradus 2011). One important manifestation of this retrenchment of services is the spatial relocation of care for the ill or disabled from state-funded organizations such as hospitals and mental institutions, to community agencies and private spaces such as people's homes (Glendinning 2009; Twigg 2006; Ungerson 2003). Policies of deinstitionalisation and early discharge from hospital are often predicated on "largely unchallenged assumptions that domestic labour will continue to underpin many public health policies" (McKie, Bowlby & Gregory 2004: 594); in other words, the spatial relocation of care also signals a shift in responsibility for service provision. At the level of the welfare state, it often entails a shift in budgetary responsibility from one government sector, such as health, to another, such as social and community care. To date, analyses of the implications of these important changes in care provision have primarily focused on health outcomes for new mothers and their newborns (Fenwick et al. 2010; Christie & Bunting 2011; Escobar et al. 2001). We broaden this focus in important ways to include post-birth care in terms of social policy, cultural norms, and the gendered care work of the family.

The state, families, gender and the culture of care

3.1 Normative assumptions and practices related to the domestic division of labour and provision of care work within the home are highly gendered: the provision of care in the home has been described as 'work with a woman's face' (Daly & Rake 2003:49). Welfare policy and provision also reflect gendered norms and ideologies in relation to care work (Daly & Rake, 2003; Boddy, Cameron & Moss 2005; O'Connor, Orloff & Shaver, 1999; Orloff 1996). State policies can either bolster the capacity of informal carers in families, or can facilitate alternative avenues of care provision in the public, private and voluntary sectors (Esping-Anderson 1999). For example, policies which offer direct payments to family carers, employment paid leaves or other forms of paid work-time reductions, support family members in their role as care providers, and are hence referred to as 'familialising'. Alternatively, state policies may be structured to reduce the extent to which the satisfaction of care needs is dependent on the family. Termed 'de-familialising', these establish mechanisms for the provision of care through publicly-funded social services, which are typically seen in democratic welfare states (Esping-Anderson 1999). Reliance on market mechanisms commodifies care arrangements, transforming care into 'products' for purchase, and the means of care provision into specialized jobs and occupations (Zimmerman et al. 2006:20).3.2 A more nuanced, gender-sensitive formulation of Esping-Anderson's conceptual categories is developed in Leitner's (2003) analysis of the effects of state policies on the caring function of the family in 15 EU member states. Leitner develops a taxonomy which differentiates between three types of familialism. The first is 'explicit familialism', in which the care work of the family is strengthened in some way by state or workplace policies, but no alternatives to familial care are provided. The second is 'optional familialism', where the care work of the family is strengthened by services and policies, but alternatives to familial care are also made available. In the latter context, families have the opportunity and right, but not an obligation, to care. The third type includes policies of 'implicit familialism', in which the implicit assumption is that the family will provide care, but the family is not explicitly supported in its caring function, nor are alternatives to familial care available. In relation to state policy and the gendered caring work of the family, Hochschild (1995) argues that it is also crucial to analyse cultural norms and the cultural valuation of care as elements of care provision. Consequently, Hochschild frames her analysis specifically in terms of the 'care deficit', defined as a situation in which the demand for care exceeds its supply.

3.3 The care deficit is the result of many factors, including, but not limited to: structural shifts in work and family; women's increased labour force participation coupled with a 'stalled gender revolution' (Hochschild 1989); the ageing of the population, and fiscal constraint inherent in public policies of neoliberal and conservative politics that cut the public supply of care. The shift from hospital to home-based care during the post-birth period raises questions about whether newly parenting mothers may become victims of this deficit in care (Hochschild 1995; Folbre 2001; England et al. 2002; Blair-Loy & Jacobs 2003).

3.4 Hochschild's approach focusses on the care deficit in terms of the relationship between the government, the family – or more particularly of gender relations within the family – and the market. Relationships between these domains determine the balance between the demand for and the supply of care work. Hochschild's analysis reveals the problems associated with women's entry into the labour force when expectations about their domestic work are not significantly altered, and when workplaces fail to provide flexible work arrangements. Hochschild's empirical work, based in the United States, demonstrates how difficult it is for employed women to provide care to their children, their elderly parents, or to community members more generally, when "notions of manhood do not facilitate male work-sharing at home" (1995:336). More importantly, Hochschild moves beyond simply tracking social trends, to plumb the depths of their meaning, both emotionally and culturally, for those involved; her analysis of care takes as central an 'emotional bond, usually mutual, between the caregiver and the cared-for' (1995:333).

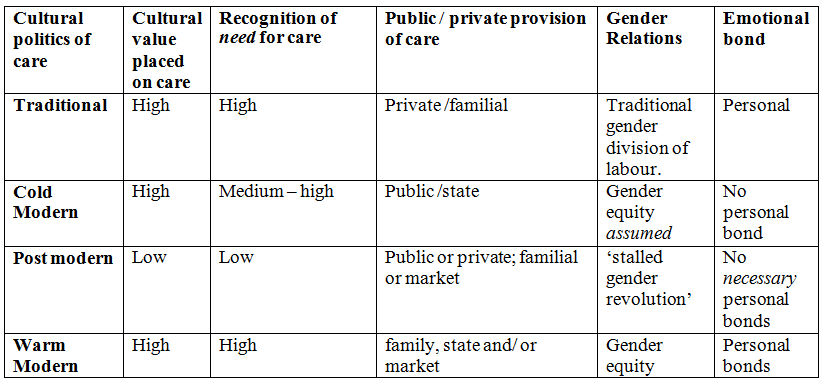

3.5 Hochschild suggests that four main 'cultural frameworks' are utilized by individuals and in public discourse in response to the care deficit. Each of these frameworks, collectively referred to as the cultural politics of care provision and summarized in Table 1, places a different value on care, on the need for care, on relations between men and women, and on relations between the public and the private sectors in their efforts to provide care.

| Table 1. Hochschild's typology: the cultural politics of care |

|

3.6 The first framework is a simple retreat to traditionalism: the reinstatement of the male breadwinner model and a gendered division of labour which locates responsibility for informal caregiving in the home and community with the stay-at-home wife /mother (Orloff 1993; O'Connor 1996). Unlikely as this scenario may be in practice in developed welfare states, where women's labour force participation rates remain high even after motherhood, the ideological strength of this image of the gendered carer continues to provide a cultural 'ideal' that resonates in some social policy.

3.7 An alternative to this cultural framework is what Hochschild (1995) refers to as the 'postmodern' model. Here, the structural conditions that produce the crisis of care and the care deficit remain, but the cultural response to dealing with it involves a substantial reframing and re-conceptualisation of the need for care. One example is the burgeoning field of psychological self-help manuals and advice books which advocate 'self-care', whether for children, the elderly or others (Hochschild 1995:339). In health care, early discharge policies for patients following serious surgery, or for new mothers sent home from hospital services within a day or so of giving birth, fail to recognise the need for social care for all women, in addition to medical care for those with health concerns. At the same time, the decline in medicalization of the post-birth period has been accompanied by a widespread government surveillance of individual women, children and families, especially those who are poor, of minority background or otherwise 'at risk' to poor health outcomes (Zadoroznyj 2006; Armstrong 1995; Bakker, & Gill 2003; Maki 2011). All of these policies illustrate postmodern approaches in so far as they legitimate the care deficit by promoting 'thinner, more restrictive notions of human well-being' (Hochschild 1995:338).

3.8 The third cultural framework is the 'cold modern': modern, because of gender equity in employment, and cold, because care is institutionally provided but impersonal (as illustrated by 12-hour day care in the former Soviet Union) (Benoit & Heitlinger 1998). Fourth is the 'warm modern' framework, premised on an egalitarian gendered division of labour, recognition of the need for care, and the high value placed on care, as evidenced through its public provision. This latter type, which recognizes and valuates personal provision of dependents, may be central to overcoming the care deficit (Zelizer 2002; Stacey 2005). How can we explain variations in post birth-care patterns in high-income countries today? Are such variations predominantly due to state-directed social and health policies, or are they determined largely by cultural norms regarding who is responsible for caring for young children? In relation to both the origins and outcomes of social policy within welfare states with respect to care ideals, Kremer (2007: 251) argues that welfare states and their linked policies are not merely "composed of sedimented values", nor can one or the other be reduced to "a mere reflection of culturally embedded ideals." Instead, complex institutional processes and powerful alliances are at work to embed such care ideals within social policy. We transition here to a review of these institutional processes and policies with the aim of linking them to both their origins in care ideals and outcomes in terms of the health of new mothers and their infants.

Post-birth care, culture and state policy

4.1 Recent trends in care provision have, in part, been informed by the cost containment concerns of third party insurers and state-provided services, resulting in radical reductions in the length of hospital stay for childbirth (Ellberg et al. 2006). From hospital stays of 11-14 days in the 1950s to average stays of 2 days or less by 2000, women's experiences of care following childbirth have changed substantially, and now take place primarily in the home and community (Eberhard-Gran, 2010; Rush, Chalmers & Enkin 1989). These structural shifts towards shorter hospital stays are informed by a professional logic of care which assumes that little, if any, medical intervention is required in the six week process during which the reproductive organs return to their non-pregnant state. Many physicians "perceive this time as requiring little assistance other than the recommended single postpartum visit," normally taking place six weeks post-birth (McGovern et al. 2007: 519; Wrede et al. 2008). This way of framing the postpartum period illustrates what the authors of one systematic review describe as a 'technocratic' cultural orientation, prevalent in many high-income countries today (Dennis et al, 2007). Such technocratic orientations contrast sharply with alternative approaches that prioritise care provision for new mothers from diverse backgrounds with wide ranging needs for support over a sustained period of time.4.2 Historical and cross-cultural analyses of the care of new mothers underscore beliefs and practices whereby "mothers are mothered" (Dennis et al, 2007: 498). Western historical practices were oriented toward the restoration of maternal health and wellbeing and typically involve the spatial separation or 'confinement' of birthing and new mothers in a period of puerperal seclusion. Within this distinctive space, newly parenting mothers and their infants were protected, nurtured, and cared for, usually by other women, typically for something around forty days following childbirth. These temporal, spatial and gendered elements of post-birth care are still common today in rural areas of low- and middle-income countries, where new mothers receive personal care from their female relatives in the first few weeks after birth, are excused or barred from household work, have their meals prepared for them, and are encouraged to rest and recuperate for a lengthy period (Eberhard-Gran 2010; Dennis et al. 2007; Kitzinger 2000: 92; Liamputong & Naksook, 2003).

4.3 Cultural norms regarding the need for care in the post-birth period have shifted substantially in recent times. The idea of 'lying in', for example, has lost currency within many high income countries, and the term has all but disappeared from the vernacular. The idea of a reasonably protracted period of time in which to recover, be cared for, and learn to deal with a new baby has been replaced with new cultural expectations of self-care and rapid recovery. Reduced length of hospital stay can be understood as part of this shift in cultural orientation. With this shift, the cultural expectation of being cared for over a reasonably protracted period of time following childbirth has changed, with expectations now often including the rapid resumption of women's former roles and responsibilities, including as paid employment (McGovern et al, 2007); pre-pregnant body weight and shape (Diedrichs, Huxley and Miller, 2009); and capacity to independently manage and care for themselves and their infants (Hedley-Ward, 2009; Wolf, 2003). Ultimately, changes in the level and duration of social support during the postpartum period place increasing responsibility on new mothers, and bear the hallmarks of the cultural re-framing of the need for care. This cultural re-orientation eschews recognition of the multi-faceted social, emotional, practical, and health care needs of new mothers for 'thin, diminished' notions of need (Hochschild 1995).

4.4 Importantly, the spatial relocation from hospital to home has shifted the demand for care from the medical sector back to the family at precisely the historical conjuncture when the capacity of the family to provide care has been drastically reduced, especially for women without strong social networks or the money to purchase support on the open market (PHAC 2009; Zadoroznyj 2007, 2009). Meanwhile, community and home-based services provided by the state have emerged in a range of forms across welfare states. While comparative research has shown that publicly-funded systems of health care in most high income countries have "steadily decreased in the form of shorter lying-in periods in postnatal wards without a corresponding increase in follow-up care at home" (Eberhard-Gran 2010: 463), little is known about what shapes the variations in how welfare states provide home and community based postnatal services, particularly in the context of cultural norms and ideals.

4.5 A well-established literature does, however, point to the increasing trend for maternal and child care services to focus on infant health, and on the surveillance of parents and their parenting skills, rather than on the provision of broad ranging support to mothers (Dennis et al, 2007; Zadoroznyj, 2009). A wide range of reports produced in the UK over the past several years, for example, has centred on the notion of "early years" or "foundation years" interventions, with the aim to reduce child poverty and inequality in life chances, and to ultimately forestall persistent social problems linked to early parental neglect (Allen, 2011; DSCF 2010; DSCF/DH 2008; Field, 2010). Within these reports, the importance of mothers' mental and physical health is cited in relation to childhood health and well-being, but short-lived, rather superficial interventions such as brief visits from "health visitors" are proposed as solutions. Additionally, such visits are framed almost exclusively in terms of expected improvements in mother-child bonding ('attachment') and/or breastfeeding rates, and their alleged consequences for early brain development and immunity, rather than any substantive improvements in the health and overall well-being of mothers themselves (Cabinet Office, 2011; DfE/DH 2011a; DfE/DH 2011b; Field, 2010; The Marmot Review, 2010). Ironically, while "parental warmth and attachment" is listed as a requirement for healthy childhood development and for forestalling social inequalities in health and overall life chances, social welfare retrenchments have reduced families' – and specifically mothers' - abilities to provide such care.

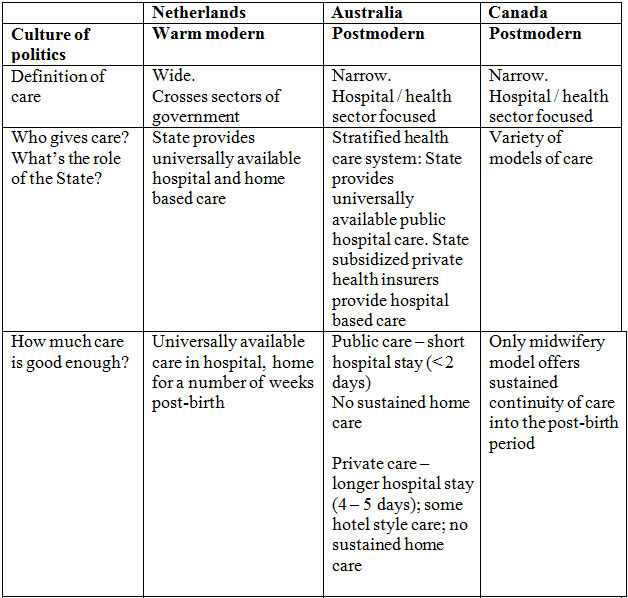

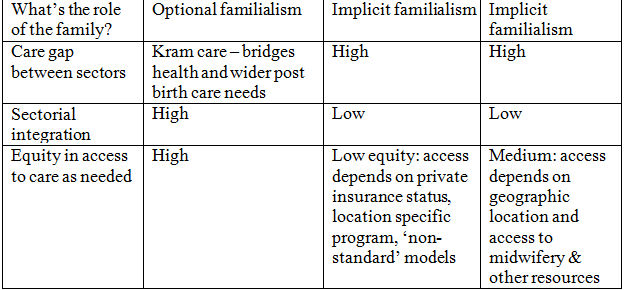

4.6 In sum, evidence from a broad range of sources suggests that post-birth care is changing in terms of how it is structured and its cultural meaning; in particular, lengths of hospital stay are declining while cultural norms about the need for a 'lying in' period have eroded. These changes in both perceptions and structuring of post-birth care are taking place at the same time as less-advantaged families become less able to provide informal care. How variable are these patterns across welfare states, and what do they mean for the care work responsibilities of families and the state? In the next part of our analysis, we examine these questions specifically in relation to the key features of post-birth care provision in three welfare states: the Netherlands, Australia and Canada. Using Hochschild's (1995) analytic framework, we describe the provision of postbirth care in terms of the cultural value placed on the need for care. Furthermore, we examine the consequences of these changes in postnatal care arrangements for the role of families and the state in care provision, and for equitable access to care. The results are summarized in Table 2. Our purpose in doing so is not to present detailed case studies; rather, following the approach of authors such as Devries et al. (2001) and Kremer (2006), we present a snapshot of each country's current post-birth care. We acknowledge that variations linked to socioeconomic status, racialized identity, and geographical location exist within these countries and explore this topic in greater detail in other work.

| Table 2. Cultural politics, care gap and equity in access to post-birth care in the Netherlands, Australia and Canada. |

|

The Netherlands

5.1 The Dutch system of maternity care provision is recognized for a number of unique features, including low rates of medical intervention during labour and delivery, safe birth outcomes for mothers and newborns, substantial percentages of births at home, autonomous roles for professional midwives, high levels of satisfaction amongst birthing women and their families, and overall cost-effectiveness (de Vries, et al. 2001). The Netherlands also has one of the longest standing state supported systems for home-based postnatal care provision (Van Teijlingen et al. 2003, 2009). This support is provided largely through a specialised occupational group of postpartum caregivers called Kraamverzorgenden, otherwise known as Maternity Care Assistants (MCA's) (Wiegers 2006). These trained caregivers work in the homes of new parents and provide a broad range of social care and support, from practical day-to-day help such as meals and laundry, to attending to the needs of older children, and providing information about issues such as breastfeeding, and "being the eyes and ears" of the midwives and other health care providers who oversee the management and care of women after childbirth (de Vries 2004:74). Kraamverzorgenden provide home-based care to new mothers for several hours per day for up to 10 days following the birth of their infant. This form of publicly provided care crosses the boundary between the health sector and the home and community care sector, alleviating the potential for a care gap/deficit.5.2 The public provision of postnatal care is considered one of the crucial 'pillars' on which the success of the Dutch system is built (de Vries 2004:74). It is a system which recognises that

'Without good postpartum care at home we cannot expect new mothers to receive their postpartum care outside of the hospital… Even the government regards postpartum care at home as an essential part of the organization of obstetric care' (Kerssens, cited in de Vries 2004:74-5).Importantly, high levels of state support minimize the potential for a 'care deficit' for Dutch families. Such support "allows women in the Netherlands to plan a home birth or a short-stay hospital birth, even if they do not have help from family, friends or neighbours" (van Teijlingen, cited in de Vries 2004:76). Symbolically, it also demonstrates the unambiguous recognition by 15 the state of the value of social care work. The widespread use of Kraamverzorgenden reflects the recognition of the need for care in the post-birth period, and its cultural value. The universal availability of the scheme makes it egalitarian, and provisions for continuity of care allow for the development of meaningful, authentic emotional bonds between paid caregivers and new mothers. Dutch families have considerable autonomy in determining who will provide post-birth care and how; the services of Kraamverzorgenden, while highly sought after, are not mandatory, and families can make whatever informal arrangements suit them.

5.3 The Dutch system can thus be described as 'warm-modern' (Hochschild 1995). Care for new mothers is recognized as necessary and important, highly valued, universally accessible, and largely provided for by the state at the interface of the health and the home and community care sectors. Families may determine the extent to which they provide care: in other words, the Dutch system is one of optional familialism (Leitner 2003). Dutch women generally receive continuous assistance from care givers – of both midwife and MCA - and hence personal, particularistic bonds have a genuine opportunity to develop, making the relationship more meaningful and satisfying.

Australia

6.1 The provision of health care in general and maternity and postnatal care in particular in Australia is shaped by several factors, including its federal system. This system comprises the Federal government and six state and two territory governments. While the Federal government provides much of the funding for health care and determines national level policy, the state and territory governments take responsibility for the provision and ongoing management of health services (Foster 2008). The provision of maternity and postnatal care is also shaped by the relatively unusual combination of a universal public health care system and a parallel private health care system in direct competition with the public sector (Benoit et al 2010). The heavily government subsidized private health insurance sector provides private hospital services for maternity care and covers a substantial proportion of the costs of care from obstetricians in private practice (Benoit et al 2010; Duckett 2005; Van Gool 2009). One of the results of the parallel public and private systems is the stratification of maternity care experiences for women in each of the sectors in terms of obstetric outcomes and postnatal stays (Laws, Li & Sullivan 2010). The majority of Australian women (around 70%) deliver their babies as patients in public hospitals where the standard model of care means there is often no continuity of provider through pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period (Department of Health and Aging 2009; Hirst 2005; Laws, Li & Sullivan 2010). Average hospital stays are short (less than 2 days), and postnatal care following discharge is highly variable. The quality, type and duration of postnatal care and follow up depends on the health district and State or Territory where Australian women give birth; by whether they give birth in a public or private hospital; and by the model of maternity care available to them. The possibilities include, but are not limited to, birth centre care; team, caseload, outreach or shared maternity care (DoHA, 2009, p. 17).6.2 Australian women report high levels of dissatisfaction, unmet needs and confusion about where to get the help they need as they transition to new motherhood (Department of Health and Aging, 2009; Hirst 2005; Yelland et al. 2007, 2008; Miller et al, 2011). Home and community care supports are often low-intensity interventions that tend to focus on information provision, infant care, infant weighing and immunisation, baby feeding or the development of peer parenting support (Sheehan et al 2009). To the extent that more sustained home and community based support is available, it is generally targeted at 'high risk' families, and the screening tools used to identify those at risk are quite intrusive (Benoit et al. 2010). Many Australian public hospitals now offer one contact – either by telephone or in person - from a midwife, but rarely is more general, practical help available through either the public health or social care sectors. Rare exceptions to this retrenchment of care do exist, such as a South Australian program of postnatal home care modeled on the MCA's in the Netherlands, but this is a small scale program available only to women birthing at one public hospital in Australia (Benoit et al. 2010).

6.3 Just over half (53%) of Australian women giving birth in private hospitals are discharged from hospital in less than 5 days, compared with 87.3% of women in public hospitals (Laws, Li & Sullivan 2010). Additional time in hospital offers private patients the opportunity to rest, establish breastfeeding routines without having to worry about the demands of running a household, and doing so in the context of readily available professional support.

6.4 As well as the considerable differences in length of hospital stay and professional support, the patterns of postnatal care provision also vary widely for public and private patients. One example is the growing trend to accommodate private patients in luxury hotels following discharge from hospital (Owen 2006). This development is noteworthy because of the marked difference in the construction of the need for care in the post-birth period according to ability to pay for private services. Accommodating postpartum women in hotels developed as a costeffective solution to high demands for private hospital accommodation in Australia. Women without medical complications may transfer to a hotel suite for their third and fourth postnatal days, with the cost of hotel-based care covered by their private health insurance. In the hotels, women remain patients of the private hospital and receive professional care from a midwife.

6.5 Following discharge home, the care that private patients receive depends on policies of the State in which they birth; for example, in the state of Queensland, the recently implemented postnatal contact policy to ensure that women receive at least one postnatal contact (either a telephone call or a home visit) within the first 10 days following birth only pertains to women who birth in public birthing facilities insofar as funding for this initiative has only gone to public maternity facilities (Queensland Government, 2012) Irrespective of where they birth, most Australian women confront similar problems of lack of availability of sustained, practical care and support provided by the State, and lack of integration between the hospital based health services and home and community based care.

6.6 In sum, the cultural politics of post-birth care in Australia are best characterised as postmodern (Hochschild 1995): they are premised on an assumption that women need little if any care after their discharge from hospital. Hotel-based postnatal care in contrast posits postbirth care as a luxury rather than a need. It is only available to the minority of women who have private health insurance and who are medically eligible. While there is no overarching policy governing who should provide care to new mothers once they are discharged from the health system, the cultural norm is that families will fill this role, and in the absence of alternatives implicit familialism frames the provision of care in the home (Zadoroznyj 2007, 2009). State provided home based care is fragmented and differs by hospital and geographic region. To the extent that community based services exist, they tend to focus on the infant rather than the mother, or on a form of surveillance aimed at identifying 'at risk' groups (Zadoroznyj 2006). Publicly funded programs which focus on broad ranging support –including health, social and practical services- for newly parenting mothers are a rarity in Australia. Rather, the Australian system is one in which a care gap is evident: community-based services often lack integration with maternity hospitals, with the result that many women slip through the cracks and receive little or no postnatal care once sent home. As for postnatal care in the hospital, Australia is remarkable for the stark contrast between what is offered in the public and private systems of care, and what this says about the cultural construction of the need for care.

Canada

7.1 The majority of Canadian women give birth in hospitals and receive maternity care from obstetricians or family physicians, although professional midwives and nurse practitioners have emerged as autonomous providers since the mid 1990's. The costs for maternity services, including salaries for physicians, midwives and other health care providers are paid for through general taxes and included as public services under the country's universal health care program, Medicare.7.2 While Canada does not have a parallel private health care system like Australia in direct competition with the public sector (Walker et al. 2005), both countries are similar in regard to many recent post-birth care developments. For example, as in Australia, the length of time Canadian women spend in hospital following childbirth has decreased dramatically, to between 24 to 48 hours after vaginal delivery (CIHI 2004). Also like Australia, Canada's public health care system covers a limited range of post-birth care services. At the federal level, this has traditionally been restricted to the provision of informational supports for the provinces and the publication of national guidelines for maternity and newborn care (Health Canada 2003). Typically, where post-birth care services do exist they are low-intensity interventions which tend towards surveillance, guidance, and referral, rather than more intensive, home-based supports for new mothers (Shaw et al. 2006).

7.3 Publicly covered post-birth care services following discharge from hospital have been reduced in some provinces to a telephone call from a public health nurse to a new mother. In other provinces, an optional home visit by either a public health nurse or a lay home visitor is still available (Benoit, Wrede & Einarsdòttir, 2011). In seven regions in Canada, publicly funded midwifery services are available for care throughout pregnancy, birth and post-birth. While the expansion of midwifery is often viewed as a major achievement for new mothers in Canada - in that midwifery care is now a viable choice for women in many regions, and services, including post-birth care services, are reimbursed through the public purse - the impacts of this expansion to date have been small. In fact, less than five percent of births in Canada are currently attended by a certified midwife (Zadoroznyj 2000). A substantial proportion of women who want to see a midwife are currently unable to find one (Association of Ontario Midwives 2007), and many pregnant women and their families must pay for their care out of pocket for both pre- and post-birth care from privatelypracticing midwives. Even in jurisdictions where midwifery services are publically-funded, recent research shows that less educated women, younger mothers, those without a partner, Indigenous women, those living in rural and remote areas or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities are less likely to have access to midwifery care during pregnancy, labour and delivery and in the post birth period (PHAC 2009).

7.4 As the role of the state and of the health care system in providing care to post-birth women has declined, a wide range of postnatal care services for purchase has grown to fill the care gap. While these services have garnered media attention in Canada (Whittaker, 2007), there currently exists no published research studies on the for-profit postnatal services that have emerged to fill such gaps in care. Compared to publicly-delivered services, however, it appears (from initial reviews of publicly-available internet advertising and service descriptions) that such private postnatal services primarily focus on mothers rather than newborn infants. The notion of a 'fourth trimester' is often discussed, and doulas or other postnatal care providers assert that their services enable mothers to ease into this new phase by ensuring that the mother's physical, emotional, and social needs are looked after. Postpartum doulas who advertise online often propose tangible, high-intensity supports such as newborn care, breast- and bottle-feeding support, child-minding services, meal preparation, household chores and management (including laundry, plant, and pet care services), errand-running, and peer support/counselling. Many of these postnatal care providers hold degrees in nursing and midwifery, and/or have completed specialized training as postpartum doulas and lactation consultants. Unlike the interventions offered though provincially directed programs, commodified forms of postnatal care appear to be highly individualized, and can be contracted out for extended periods of time (i.e., an overnight stay, or an entire week).

7.5 Unfortunately, the relatively high costs of hiring private postnatal care providers make these forms of support accessible only to those who are able to pay for them. Providers who advertise online generally charge around $25(CAD) on a per-hour basis, or anywhere from $100 to $1000(CAD) for overnight or week-long package deals, respectively. Research studies in this emerging area of practice are needed to determine scope of practice and outcomes for mothers and their infants. There is currently no information available on user demographics, patterns of use, or outcomes associated with these forms of commodified care, though such information would offer insight into the types and levels of unmet needs that exist.

7.6 In sum, the provision of post-birth care in Canada is stratified by geographical location, social status factors, and capacity to pay for services on the market (Kornelsen 2003; Sandall et al. 2009; Benoit et al. 2010). Early discharge from hospital, coupled with limited provincially-provided post-care support, especially in jurisdictions without public provision of midwifery, leaves new mothers and their families with two main alternatives: to rely on their own resources for care provision, or to rely on the market for the purchase of care services.

Summary & Conclusion

8.1 In this paper we have argued that post-birth care in high-income countries is a product of both society and culture, of welfare state policies and of cultural norms. We have linked our analyses of state policies and cultural norms in The Netherlands, Canada, and Australia by using a typology of care framework developed by Hochschild (1995), which allows for productive comparisons in terms of their approaches to care provision. Furthermore, we apply the 'cultural politics of care' framework to our analyses of post-birth care in these welfare states - all of which have endorsed neoliberal policies to limit government expenditures, reduce deficits and expand surveillance of populations- to highlight the implications for equitable access to care, for the emergence of a 'care gap', and for the role of the family (or markets) in the provision of postbirth care.8.2 We compared in broad strokes the provision of post-birth care for mothers in three welfare states. Our overview reveals the extent to which the care of early parenting women (and their infants) is located in the often ill-defined terrain where the health and social care branches of the welfare states intersect. In a country such as The Netherlands, the two branches of the welfare state have cooperated and integrated to such an extent that they are able to meet the care needs of women in the postpartum period. In Australia and Canada, however, these branches work more or less in silos. It is within the latter contexts that a care gap is most obvious - the state does not provide formal care, and the informal care system no longer functions to fill care needs unaddressed by public institutions. Disadvantaged women, therefore, who do not have the means to pay for services out of pocket, fall through the safety net in these contexts. The cultural norms surrounding post-birth care in The Netherlands, on the other hand, are embedded in state policy which continues to recognize the need for care in the post-birth period for all new mothers, while the public funding of an integrated, thorough system of care demonstrates the value placed on post-birth care in state policy and cultural norms.

8.3 Care for new mothers in The Netherlands, therefore, is recognized as necessary and important, highly valued, universally available, and largely provided by public institutions. One of the critically important features of this model of care provision - in terms of its consequences for care delivery and outcomes - is that is allows families to determine the extent to which they act as care providers. Within this system of optional familialism (Leitner 2003), Dutch women are also far more likely to experience continuity of carer with both a midwife and MCA, and therefore to develop bonds with their carers that positively affect birthing experiences and postnatal outcomes (De Vries et al. 2001; Van Teijlingen et al. 2003; Wiegers 2006). The Dutch system thus falls within Hochschild's (1995) categorization of warm modern on almost all dimensions: the cultural value placed on care, the recognition of the need for care, the public provision of care, and continuity of carer. Access to care is equitable, there is little or no care gap, and families are not required to provide care, but rather their involvement is optional.

8.4 In contrast, the cultural politics of post-birth care in Australia and Canada are, to a large extent, postmodern (Hochschild 1995): they are premised on the often mistaken assumption that women need little if any care after their discharge from hospital, an understanding which is, in turn, based on very narrow conceptions of care itself. Where government-based home care is provided within these contexts, it is generally limited in scope, fragmented in terms of its provision across multiple carers, and differs in type and quality between hospitals and geographic regions. To the extent that community based services exist, they tend to focus on the infant rather than the mother, or on a form of surveillance aimed at identifying 'at risk' groups. Publicly-funded programs for newly parenting mothers which focus on broad ranging support –including health, social and practical support services - are a rarity in Australia. Instead, the Australian system is one in which a care gap is evident: community based services often lack integration with birthing hospitals, and the result is that many women fail to receive the care they need. In Canada, midwives provide social care to a small percentage of new mothers but these tend to be those who are more advantaged. In both of these countries, the family and the market are variously called upon to fill the care gap, though implicit familialism (Leitner 2003) looms large in terms of framing the provision of post-birth care in the home. As for postnatal care in the hospital, the Australian system contains remarkable contrasts in terms of services that are offered in public versus private tiers, and speaks volumes of the culturally constructed need for care that underlies such a system. The luxury alternative of five star hotel based postnatal care reconstructs the need for care as a form of 'pampering' – nice for those who can afford it, but hardly something everyone should feel entitled to. While Canada has not moved so far in this direction of a parallel private post-birth care system, the use of private doulas and other forms of post-birth care in Canada indicate a general lack of societal recognition of the need for equitable care for all new mothers.

Limitations and Future Directions

9.1 Our analyses indicate that in the provision of post-birth care, as with other domains of care work, welfare state policies of publicly provided care shape the role of families (and markets). Hochschild's multi-faceted typology of care approach provided us with a useful framework within which to examine both the specificity of and linkages between The Netherlands, Australia and Canada in terms of their systems of care provision, and the cultural ideologies that underlie them. Nonetheless, authors such as Kremer (2006) have argued that Hochschild's model of care ideals is a priori normative because she seems to prefer the warm modern, and that such a model has difficulty historicizing the emergence of different approaches and ideals within various countries. Following Kremer (2006), we acknowledge that the complexity and moral problematics of care deficits and dilemmas likely demand dynamic (and perhaps "bricolage"- style) models of care policy and provision. For this reason, future research is needed to further investigate the differential origins (ideological and otherwise) of current systems of postnatal care provision in the three countries examined, and to conceive of expanded ideals of care that are not moralistic in and of themselves.9.2 Although we argue that state policies in Australia and Canada are best described as forms of implicit familialism, it is clear that some individuals are turning to the market rather than family, or perhaps a combination of both familial and commodified care to meet their care needs in the post-birth period. Within the scope of this paper, we are not able to determine whether this use of market mechanisms for the purchase of 'commodified' care constitutes an example of defamilialisation. However, to the extent that individual mothers or families rely on the market for care provision, issues of equity and quality of care are pivotal (Folbre & Nelson 2000; Pocock 2006), and thus require further examination within future work on postnatal care provision. The impact of the current care deficit on new mothers who are disadvantaged due to low income, younger age, Indigenous background, racial minority status and chronic illness also needs further research.

9.3 Finally, it was not within the scope of this paper to thoroughly investigate the underlying gender relations upon which the cultural politics of care are based, including the impact of different post-birth care regimes on new fathers (Fox, 2009). This will be a crucially important next step in laying the groundwork for future research on postnatal care provision, and for the development of more equitable postnatal care policies, including in the three countries studies investigated in this paper.

References

ALLEN, G. (2011) Early Intervention: Smart Investment, Massive Savings: The Second Independent Report to Her Majesty's Government'. Cabinet Office, UK Government.ARMSTRONG, D. (1995) 'The rise of surveillance medicine', Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 17 pp. 343-404.

ASSOCIATION OF ONTARIO MIDWIVES (2007) Ontario Government delivers more midwives. Press release. Toronto: Association of Ontario Midwives.

BENOIT, C. & Hallgrimsdottir, H. (Eds.). (2011) Valuing care work: Comparative perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

BENOIT, C. & Heitlinger, A. (1998) Women's health care work in comparative perspective: Canada, Sweden and Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic as case examples. Social Science and Medicine, 47(8), 1101-1111. BENOIT, C., Shumka, L., Phillips, R., Hallgrímsdóttir, H., Hankivsky, O. & Kobayashi, K., Reid, C. & Brief, E. Explaining the health gap between girls and women in Canada. Sociological Research Online, 14 (5). Retrieved from: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/5/9.html.

BENOIT, C., Zadoroznyj, M., Hallgrimsdottir, H., Treloar, A. & Taylor, K. (2010) Medical Dominance and Neoliberalisation in Maternal Care Provision: The Evidence from Canada and Australia. Social Science & Medicine. 71, 475-481.

BENOIT, C., Wrede, S. & Einarsdòttir, T. (2011) The impact of neo-liberalism on maternity care work in different welfare states: Canada in cross-national perspective. In C. Benoit & H. Hallgrimsdottir, H. (Eds.) Valuing care work: Comparative perspectives (pp. 45-64). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

BAKKER, I. & Gill, S. (eds) Power, Production and Social Reproduction. New York, N.Y., Palgrave.

BLAIR-LOY, M. and Jacobs, J. (2003) 'Globalization, work hours and the care deficit among stockbrokers', Gender and Society, Vol. 17, No 2 pp. 230-49.

BODDY, J., Cameron C., and Moss, P. (eds) (2005) Care Work: Present and Future. London: Routledge.

CABINET OFFICE (2011) Opening Doors, Breaking Barriers; A Strategy for Social Mobility. UK Government.

CARGILL, Y. and Martel, M.J. (2007) 'Postpartum maternal and newborn discharge', Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of Canada Vol. 29, No 4 pp. 357-9.

CHRISTIE J. and Bunting, B. (2011) 'The effect of health visitors' postpartum home visit frequency on first-time mothers: cluster randomised trial', Int J Nurs Studies, Vol. 48, No 6 pp. 689-702.

CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF HEALTH INFORMATION (2004) Giving Birth in Canada: Providers of Maternity and Infant Care. Ottawa: CIHI.

DALY, M. and Lewis, J. (2000) 'The concept of social care and the analysis of contemporary welfare states', British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 52, No 2pp. 281–298.

DALY, M. and Rake, K. (2003) Gender and the Welfare State, Cambridge: Polity Press.

DE VRIES, R., Benoit, C., van Teijlingen, E. R., and Wrede, S. (eds) (2001) Birth by design: Pregnancy, maternity care, and midwifery in North America and Europe. New York: Routledge.

DE VRIES, R. (2004) A pleasing birth: Midwives and Maternity Care in the Netherlands. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

DE VRIES, R. Wrede, S., Benoit, C. and Van Teijlingen, E. (2004). 'Making maternity care: The consequences of culture for health care systems' in H. Vinken, J. Soeters and P. Ester (eds) Comparing cultures, Tilburg: IRIC / Tilburg University pp. 209-23.

DECLERCQ, E., Sakala, C., Corry, M.P., and Applebaum, S. (2008) New Mothers Speak Out: National Survey Results Highlight Women's Postpartum Experiences. New York: Childbirth Connection.

DENNIS, C., Fung, K., Grigoriardis, S., et al (2007) 'Traditional postpartum practices and rituals: a qualitative systematic review', Women's Health, Vol. 3, No 4 pp. 487-502.

DFE/DH (2011a) Families in the Foundation Years, Evidence Pack, Department of Health and Department of Education, UK Government.

DFE/DH (2011b) Supporting Families in the Foundation Years, Department of Health and Department of Education, UK Government.

DIEDRICHS, P., Huxley, L., and Miller, Y. (2009) 'Media Messages about mothers' bodies: from "blooming marvellous baby bump" to "yummy mummy no tummy"' presented at The Mother and History: Past / Present / Future Conference, University of Queensland, 2-4 July 2009.

DSCF/DH (2008) 'The Child Health Promotion Programme, Pregnancy and the first five years of life', Department for Children, Schools, and Families and Department of Health, UK Government.

DCSF (2010) Early Intervention: Securing Good Outcomes for all Children and Young people, Department for Children, Schools, and Families, UK Government.

DUCKETT, S. (2005) 'Living in the parallel universe in Australia', Canadian Medical Association Journal, Vol. 173, pp. 745 – 747.

EBERHARD-GRAN, M., Nordhagen, R., Heiberg, E., Bergsjø, P., Eskild, A. (2010) 'Postnatal care: a cross-cultural and historical perspective', Arch Women's Mental Health, Vol 13 pp. 459-466.

EHRENREICH, B., and Hochschild, A. (2002) Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy. New York: Metropolitan Press.

ELATTAR, A. , Selamat, E.M., Robson, A. and Loughney, A. (2008) 'Factors influencing maternal length of stay after giving birth in a UK hospital and the impact of those factors on bed occupancy', Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Vol 28., No. 1 pp. 73-76.

ELLBERG, L., Hogberg, U, Lundman, B, and Lindholm, L. (2006) 'Satisfying parents' preferences with regard to various models of postnatal care is cost-minimizing', Acta Obstetrica et Gynecolgica, Vol. 85pp. 175-181.

ENGLAND, P., Budig, M, and Folbre, N. (2002) 'Wages of virtue: The relative pay of care work', Social Problems, Vol. 49 pp. 455–73.

ESCOBAR, GJ, Braveman PA, Ackerson L, Odouli R, Coleman-Phox K, Capra AM, Wong C, Lieu TA. (2001) 'A randomized comparison of home visits and hospital-based group follow-up visits after early postpartum discharge', Pediatrics, Vol. 108, No. 3pp. 719-27. [doi:0.1542/peds.108.3.719]

ESPING-ANDERSEN, G. (1999) Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [doi:0.1093/0198742002.001.0001]

FIELD, F. (2010) 'The Foundation Years: preventing poor children becoming poor adults': The Report of the Independent Review on Poverty and Life Chances. Cabinet Office, UK Government.

FINK, J. (2004) Care: Personal Lives and Social Policy. Bristol: The Policy Press.

FOLBRE, N. and Nelson, J.A. (2000) 'For Love or Money - Or Both?' The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 14, No. 4pp. 123-140. [doi:0.1257/jep.14.4.123]

FOX, B. (2009). When Couples Become Parents. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press.

GLENDINNING, C. (2009) 'Cash for care: implications for carers', Geneva Association Health and Ageing Newsletter, Vol. 21pp. 3-6.

GLUCKSMANN, M. and D. Lyon (2006) `Configurations of Care Work: Paid and Unpaid Elder Care in Italy and the Netherlands', Sociological Research Online, Vol. 11, No. 2 pp. 101-118 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/2/glucksmann.html>. [doi:0.5153/sro.1398]

GOULET, L., D'Amour, D. and Pineault, R. (2007) 'Type and Timing of Services Following Postnatal Discharge: Do They Make a Difference?' Women and Health, Vol 45, No 4, pp. 19-39. [doi:0.1300/J013v45n04_02]

GREVE, B. (2011) 'Editorial Introduction: The Nordic Welfare States – Revisited', Social Policy & Administration, Vol. 45 pp. 111–113. [doi:0.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00758.x]

HEALTH CANADA (2003) Canadian Perinatal Health Report 2003. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

HEDLEY-WARD, J. (2009) You Sexy Mother: Empowering mums to lead a vibrant, sexy and authentic life. Auckland: Exisle Publishing.

HIRST, C. (2005) Re-Birthing, Report of the Review of Maternity Services in Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

HOCHSCHILD, A. (1995) 'The Culture of Politics: Traditional, Postmodern, Cold-Modern and Warm-modern Ideals of Care', Social Politics, pp. 331-346.

HOCHSCHILD, A. (1989) The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. New York: Viking.

KITZINGER, S. (2000) Rediscovering Birth. New York: Pocket Books.

KORNELSEN, J. (Ed.) (2003). Midwifery: Building our Contribution to Maternity Care. Proceedings from the Working Symposium; 2002 May 1-3; Vancouver, Canada. Vancouver: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women's Health.

KREMER, M. (2006) 'The Politics of Ideals of Care: Danish and Flemish Child Care Policy Compared', Social Politics, Vol. 13, No. 2 pp. 261-285.

LAWS, P.J., Li, Z. and Sullivan, E.A. (2010) 'Australia's mothers and babies 2008', Perinatal statistics series, Vol. 24, Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

LEITNER, S. (2003) 'Varieties of Familialism: The caring function of the family in comparative perspective', European Societies, Vol. 5, No. 4 pp. 353-375.

LIAMPUTTONG, P., & Naksook, C. (2003) 'Life as Mothers in a New Land: The Experience of Motherhood Among Thai Women in Australia', Health Care for Women International, Vol. 24 pp. 650-668.

MAKI, K. (2011) 'Neoliberal Deviants and Surveillance: Welfare Recipients under the watchful eye of Ontario Works', Journal of Surveillance and Society, Vol. 9, No. 1 pp.: 47-63.

MCGOVERN, P. (2007) 'Mothers' health and Work-Related Factors at 11 Weeks Postpartum', Annals of Family Medicine, Vol 5/6 Nov/Dec, pp. 519-527. [doi:0.1370/afm.751]

MCKIE, L., Bowlby, S., Gregory, S. (2004) 'Starting Well: Gender, Care and Health in the Family Context', Sociology, Vol. 38, No. 3 pp. 593-611. [doi:0.1177/0038038504043220]

NADER, C. (2005) 'The hotel's on the health fund tab: For complication free births, a five-star stint can cut waiting lists and angst', The Age, 14 Nov. Online: <http://www.theage.com.au/news/National> Accessed 14 Nov 2008.

O'CONNOR, J. (1996) 'From women in the welfare state to gendering welfare state regimes', Current Sociology, Vol. 44 pp. 1–125.

O'CONNOR, J.S., Orloff, A.S. & Shaver, S. (1999) States, Markets, Families: Gender, Liberalism and Social Policy in Australia, Canada, Great Britain and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [doi:0.1017/CBO9780511597114]

OAKLEY, A. (1992) Social Support and Motherhood: The Natural History of a Research Project. Oxford: Blackwell.

ORLOFF, A.S. (1996) 'Gender in the Welfare State', Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 22: pp28. [doi:0.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.51]

OWEN, M. (2006) 'Bliss at the five-star maternity hotel', The Advertiser, 19 Sept. Online: <http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0, 25197> Accessed 21 Feb 2009.

PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY OF CANADA (2009). Mothers' voices. Ottawa: PHAC.

POCOCK, B. (2006) The Labour Market Ate My Babies: Work, Children and a Sustainable Future. Federation Press, Sydney.

RUSH, J., Chalmers, I., Enkin, M. (1989) 'Care of the new mother and baby'. In Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJ (eds): Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989.

SAUNDERS, P. and C. Deeming 2011 'The Impact of the Crisis on Australian Social Security Policy in Historical Perspective', Social Policy and Administration, Vol. 45, No. 4pp. 371 – 388. [doi:0.1111/j.1467-9515.2011.00780.x]

SHAW, E., Levitt, C., Wong, S., Kaczorowski, J. (2006) 'Systematic Review of the Literature on Postpartum Care: Effectiveness of Postpartum Support to Improve Maternal Parenting, Mental Health, Quality of Life and Physical Health, Birth, Vol. 33, No. 3 pp. 210-220. [doi:0.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00106.x]

STACEY, C. (2005) 'Finding dignity in dirty work: The constraints and rewards of low-wage home care labour', Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 27 pp. 831–54. [doi:0.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00476.x]

THE MARMOT REVIEW (2010) 'Fair Society, Healthy Lives: A Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010'. Review of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010. Online: <http://www.ucl.ac.uk/gheg/marmotreview>, Accessed May 14, 2012.

TWIGG, J. (2006) The Body in Health and Social Care. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

UNGERSON, C. (2003) 'Commodified Care Work in European Labour Markets', European Societies, Vol. 5, No. 4 pp. 377-396.

UNGERSON, C. and Yeandle, S(eds) (2007) Cash for Care in Developed Welfare States. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

VAN GOOL, K. 2009 "Maternity Service Review: Australia" Health Policy Monitor, April 2009. Online: <http://www.hpm.org/survey/au/a13/1>, Accessed May 1, 2012.

VAN TEIJLINGEN, E., Sandall J, Wrede S, Benoit C, DeVries R, Bourgeault I. (2003) 'Comparative Studies in Maternity Care', RCM Midwives Journal, Vol. 8,pp. 338-340.

VAN TEIJLINGEN, E., Wrede, S., Benoit, C., Sandall, J. & DeVries, R. (2009) 'Comparative analyses of youth sex education and maternity care in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands: The importance of social and cultural factors', Sociological Research Online, Vol. 14, No. 1. <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/1/5.html>.

WALKER, A., Percival, R., Thurecht, L., and Pearse, J. (2005) 'Distributional impact of recent changes in private health insurance policies', Australian Health Review, Vol. 29 pp. 167–177. [doi:0.1071/AH050167]

WARNER, M.E. & Gradus, R.H.J.M. (2011) 'The Consequences of Implementing a Child Care Voucher Scheme: Evidence from Australia, the Netherlands and the USA', Social Policy & Administration, Vol. 45, No. 5 pp. 569–592.

WHITTAKER, S. (2007) 'Demand sparking growth. Private clinics expanding', The Montreal Gazette 13 January. Online: <http://www.Canada.com network> Accessed 22 Jan 2008.

WIEGERS, T.A. 2006 'Adjusting to motherhood: maternity care assistance during the postpartum period: how to help new mothers cope', Journal of Neonatal Nursing, Vol. 12 pp. 163-171. [doi:0.1016/j.jnn.2006.07.003]

WILLMS, J.D. (2002). Vulnerable children: findings from Canada's longitudinal survey of children and youth. Alberta: University of Alberta Press.

WOLF, N. (2003) Misconceptions: Truth, Lies and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood. New York: Anchor Books.

WREDE, S., C. Benoit and T. Einarsdottir. (2008) 'Equity and Dignity in Maternity Care Provision in Canada, Finland and Iceland', Canadian Journal of Public Health, Vol. 99, No. 2 (special supplement) pp. 16-21.

YELLAND, J., McLachlan, H., Forster, D., Rayner, J. and Lumley, J. (2007) 'How is maternal psychosocial health assessed and promoted in the early postnatal period? Findings from a review of hospital postnatal care in Victoria, Australia', Midwifery, Vol. 23 pp. 287-297.

YELLAND, J, Forster, D., McLachlan, H, and Rayner, J. (2008) 'A submission regarding care in the early postnatal period', National Maternity Services Review: Australia Department of Health and Aging. Available at: <http://www.health.gov.au> [Accessed 10 Feb 2011].

ZADOROZNYJ, M. (2006) ‘Surveillance, support and risk in the postnatal period’ Health Sociology Review 15, 4:353-363. [doi:0.5172/hesr.2006.15.4.353]

ZADOROZNYJ, M. (2007) ‘Postnatal care in the community: Report of an evaluation of birthing women’s assessment of a postnatal home care program’

ZADOROZNYJ, M. (2009) ‘Professionals, Carers or Strangers? Liminality and the Typification of Postnatal Home Care Workers’ Sociology 43 (2):268-285. [doi:0.1177/0038038508101165]

ZELIZER, V.A. (2002) 'How care counts', Contemporary Sociology, Vol. 31pp. 115–19.

ZIMMERMAN, M., Litt, J., and Bose, C. (2006) Global Dimensions of Care work and Gender. Stanford: Stanford University Press.