The Sleeping Lives of Children and Teenagers: Night-Worlds and Arenas of Action

by Jo Moran-Ellis and Susan Venn

University of Surrey

Sociological Research Online 12(5)9

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/9.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1606

Received: 22 Jan 2007 Accepted: 14 Aug 2007 Published: 30 Sep 2007

Abstract

Most research into sleep, even that which includes a sociological dimension, tends to focus on sleep outcomes, in effect following an agenda set by the natural sciences and psychology. The work reported in this paper engages with the material and social dimensions of sleep from within social constructionist and interactionist frameworks, seeking to explore and theorise the meaning and experience of sleep from the perspective of the sleeper. In doing this, we examine how contemporary constructions of sleep and constructions of childhood and adolescence arise and are linked in the UK context. Sleep time tends to be constructed as empty of activity other than sleeping and devoid of the sorts of interactions that characterise wakeful day-time. However, a grounded analysis of qualitative data generated with 9 children and 20 teenagers suggested that the assumption of absence of activity and interaction was misleading: their nights were populated by a range of actors, presences and activities. Placing our focus on these aspects of our participants' accounts of their sleep we found that the temporal, spatial and interactional dimensions of routine sleep served to create a definable arena of action (Hutchby and Moran-Ellis 1998) which was marked out both materially and socially. We conceptually frame this arena of sleep as a night-world (Moran-Ellis, 2006).

Keywords: Sleep, Children, Night-Worlds, Social Construction, Interaction, Teenagers, Arenas of Action

Introduction

1.1 As is argued in this special issue, sleep and the practices associated with it bear sociological interrogation as phenomena in their own right. Much research into sleep, even that which includes a sociological dimension, tends to follow an agenda set by the natural sciences and psychology which focuses on the causes and outcomes of 'poor' sleep. For example, research on pre-adolescent and adolescent sleep has focused on how 'counterproductive' sleep patterns arise in teenage years (Graham, 2000), and how the paraphernalia of the teenage bedroom, from television to computers to mobile phones, impacts on bedtimes, sleep time and quality of sleep (Van den Bulck, 2003, 2004). In contrast the work reported in this paper draws on social constructionist and interactionist frameworks in sociology to explore sleeping and bedtime from the perspective of the sleeper. Specifically we explore the meanings of the contexts and practices that attend the act of sleeping for children and teenagers, examining how these link with contemporary constructions both of sleep and of childhood and adolescence in the UK context. Issues of privacy, self-determination, and control over material space emerge as key for participants, particularly in relation to the construction of inter-generational and sibling relationships, coupled with opportunities for self-hood. In addition, our research with children and young people suggests that their experience of sleep and night-time is of a time populated by a range of actors, presences and activities despite being removed from the usual spaces of the daytime. Drawing on our participants' accounts of their sleep and sleep practices we explore how the temporal, spatial and interactional dimensions of routine sleep create a definable night-world (Moran-Ellis, 2006) – an arena of action (Hutchby and Moran-Ellis 1998) which is marked out both materially and socially, and which is qualitatively different from the night-time activities of adults (see Hislop and Arber, 2003) in respect of the range of actors and the type (and for teenagers – the degree) of interaction in which our participants engaged.The data

2.1 This paper draws on the analysis of the accounts provided by children and young people of their experiences of sleep in two small-scale studies. In the 'children study', 9 children between the ages of 7 and 11 yrs were interviewed using a qualitative approach about their experiences of sleep. They also completed a questionnaire about each night's sleep for a week, and their sleep activity was recorded using an 'Actiwatch' (Meadows, 2005). In addition, a video-recording, directed by the child, was made of their bedroom space. The interviews were tape-recorded with permission and transcribed for analysis using a grounded theory approach (Coffey and Atkinson, 1996). This paper reports the analysis of only the interviews for the child study.2.2 The second study involved teenagers. Initially two single-sex focus groups of five participants each were held with teenagers aged 13 and 14 years. Following the focus groups, the participants completed a daily audio sleep diary for one week (Hislop and Arber 2003; Hislop et al 2005). Seven diaries were completed and returned to the researcher. Both the focus groups and audio sleep diaries were fully transcribed. A further ten respondents, age 13-18 years, who had not taken part in the focus groups, also completed sleep diaries in a medium of their choice: web log (blog), written, daily email entries, or recorded audio-diary. Four chose the blog, one chose to do a written diary, two emailed their diary entries, and three used the audio-recording method. The data drawn on here include the focus group discussions and the sleep diaries.

2.3 For the children study, consent to participate was initially gained from a parent, and then each child's own assent was sought. For the teenage study, written informed consent was obtained from each participant in advance, and consent was also obtained from the parents of those under 16 years. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained, and all names used in this paper are pseudonyms.

2.4 We start the paper by considering how children and young people move into the arena of the night-world. We then go on to examine what characterises this world and how sleep figures within it. We conclude with some reflections on the construction of sleep and its intersections with constructions of 'not being an adult'.

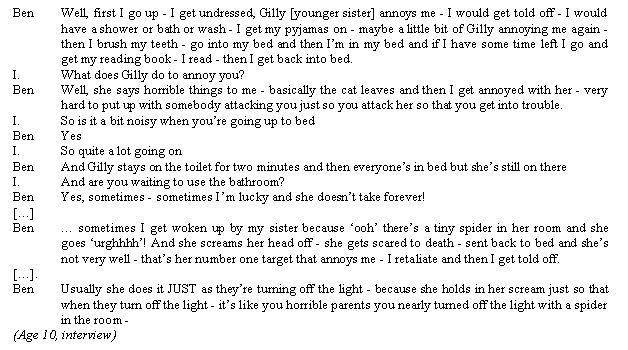

Leaving the day world: time for bed

3.1 In the UK, entry into the realm of sleep is domestically institutionalised through specific rites, rituals and practices. These usually involve at least a change of clothing and a move to occupation of a physical space where it is appropriate to withdraw from the social interactions that make up the daytime in order to pursue sleep – usually a bed in a bedroom. Other rituals may accompany these two changes, and all these activities are strongly linked temporally to a specific time for serious sleeping – night-time – in contrast to daytime sleeping which may take place in locations other than the bedroom and does not necessarily involve a change into nightwear. In many ways this is so culturally familiar and mundane as to be unremarkable. However, whilst for the children in our study the move from the waking to sleeping world did indeed involve changing into nightwear and getting into bed, this was not a brief, nor uncontentious, set of tasks. Rather it was a transition process saturated with issues of power and generational orderings. The children were guided, or cajoled, through a series of activities which moved them into the space designated as their sleeping area. These activities were highly embodied and principally involved physical relocation of the children from the shared public spaces of their home – the living room perhaps or the kitchen – towards their beds, accompanied by hygiene-related activities such as brushing of teeth, bathing or showering, and using the toilet (see also Williams, Lowe and Griffiths this volume). Other activities were often also involved, orientated more to settling the children, through inducing bodily stillness or quietness, such as watching a particular television programme, reading a book or being read to, or listening to a story tape. All these elements were orchestrated and ordered by parents so that they converged temporally to accomplish 'bedtime', the aim being to produce children who were 'ready' for sleep, ie ready to leave the waking realm. However, despite the complex and stable arrangements involved this transition period was often characterised by the children in their accounts as embedded within the dynamics of family life and replete with false starts, counter-moves, and resistances. With regard to the latter, Ben's account of bedtime was interesting, illustrating the playing out of sibling issues around the process of going to bed:

|

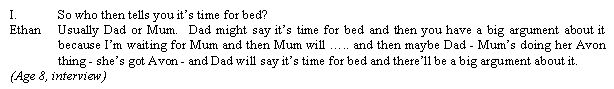

whilst Ethan recounts more direct resistance:

|

3.2 Determining the point at which children will enter into their night-world appeared to lie primarily in the hands of parents, although their efficacy in bringing about this transition was vulnerable to children's own reluctance to disengage from the waking world.

3.3 Some children presented accounts which placed more emphasis on the sense of a routine around the transition rather than conflict with parents. Daisy indicated her reading of the arrival of her bed time[1] by the finishing of a television programme:

|

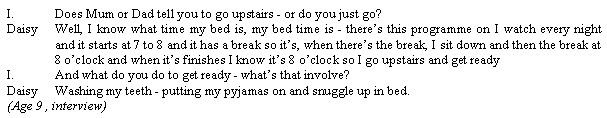

3.4 Harry was more concerned to establish how the time for going to bed held meaning in relation to the demands of the waking world in his life and his biography in chronological terms:

|

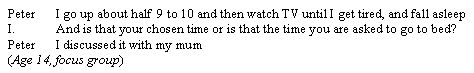

3.5 Children's presences in worlds that are essentially controlled by adults are routinely subject to regulation in terms of time and space. Eviction from the social spaces of the waking world emerged as a significant pre-requisite for sleeping – removal from those parts of the home not to do with sleep or preparation for sleep – and this, by and large, was ordered and established by adults. Juxtaposing this adult ordering of presence and eviction from the waking world with the same process for teenagers, from the perspective of the teenagers in our study, we can see how being older brings with it the privilege both of choosing when to go to bed and how this will be accomplished. Whilst parents were still controlling and regulating the time that teenagers had to go 'up to bed', there was evidence of greater flexibility for this age group about what 'bedtime' meant in contrast to the children for whom it meant being in bed, the lights off, and going to sleep:

|

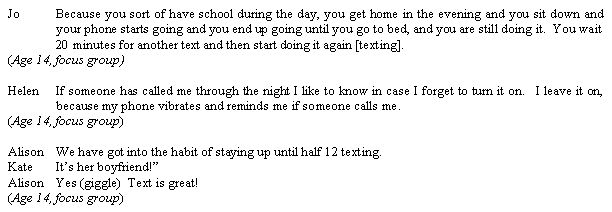

3.6 Negotiations about bedtime were confined to the timing of when the teenagers moved to their sleeping space, and did not include discussions on when they should disengage from the waking world; the decision of when to go to sleep was essentially their own, and what they might do in their bedrooms before going to sleep was essentially their own. Most of the teenage respondents talked about texting their friends or talking to them on their mobiles or via the internet from their bedrooms during this pre-sleep time whilst others chose to read for long periods perhaps.

3.7 For the children and the teenagers the time of transition to sleep appears to be a twin process of moving (or being moved) to the periphery of the day world and preparations for crossing from there into a night-world. Moving into the space of the bedroom and changing into nightwear effectively evicts the child from the day-world by closing down the possibilities of being in public spaces, or being outside, or engaging in interactions outside the household. Whilst this is also the case up to a point for teenagers there are two key differences: the role of parents in ordering these changes is not so evident as it is for children, and possibilities of social interaction with friends and others who are not in the same domestic space are not closed down. On the contrary, moving into the bedroom may open up more possibilities of extensive interaction with others by affording opportunities for un-interrupted (and perhaps unregulated) use of mobile phones and/or the internet. For teenagers the terms of eviction from the day world and mechanisms of moving (or more rightly being moved) towards its periphery were less easily maintained by adults when teenagers sought (some) rights to determine their own presence and engagement in the day world. This claim on self-determination is tied to moves to achieve the status of adult, a status characterised in contemporary times by ideals of self-regulation and self-determination. The cumulative effect is that for teenagers the transition from the waking world to the sleeping world becomes limited to spatial re-location into a bedroom and this changes the nature of the teenage night-world compared to that of children. Relocation to the bedroom symbolically removes the teenager from the waking world but use of the internet or mobile phones to be in contact with friends creates a more fluid border between waking/day-time and sleeping/night-time worlds – we examine this latter activity in more detail later.

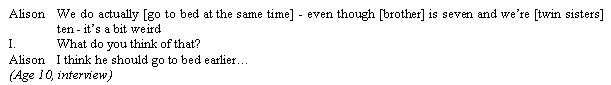

3.8 In the children's accounts, the right to remain on the day side of the border between the arenas of wakefulness and sleeping was strongly policed by parents but this was understood and experienced by the children generally as age-related. Being allowed to stay up later than one's younger siblings was treated as a privilege attained with increasing age. The granting of this privilege by parents was monitored by the children, although many of them noted how the proper age-related distribution of these rights was honoured more in the breach than in the observance:

|

3.9 Entry into the night-world then was produced through inter-generational orderings (Mayall and Alanen 2001) albeit differentially for children and adolescents. Attended by rituals of transition, the move towards sleep is best characterised as a move to the periphery of the day world in the first instance which for the children in our study is largely controlled by adults (parents) whilst for teenagers increasing conferment and appropriation of rights of self-determination configures the periphery and the move differently.

Light and darkness in the night-world

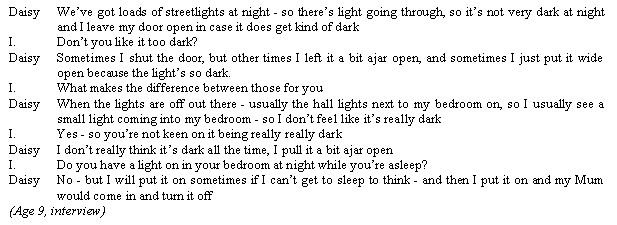

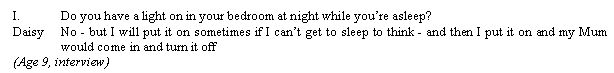

4.1 Generally we associate sleep with night time and hence with darkness. The issue of darkness and sleep arose several times in the interviews with the children. The absence of light and the presence of darkness at night was a material feature which signified a boundary between night and day worlds for children. However, they frequently reported negotiations with their parents about how dark their rooms should or could be in the night. This contestation about who controls light/dark reflects distributions of power between adults and children, and challenges to those distributions. The control of lighting level reflected two competing issues: a fear of complete darkness on the part of the child versus a view on the part of parents that too much light will prevent or delay sleep. The resolution of the problem of there being enough light in the child's room to banish fears but enough darkness to induce, or help induce, sleep often lay in leaving the bedroom door open and a light on outside the room. The critical degree of how far ajar the door was left was for some children a matter of negotiation with their parents whilst others either exercised more autonomy, as in Daisy's extract below, or the matter has long been settled and institutionalised within the household:

|

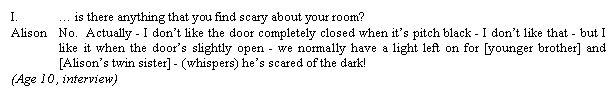

4.2 Alison distanced herself from the need for light at night, attributing the provision of light from the hallway as being primarily for her younger brother's benefit; fear of the dark was often positioned as age-related by the children in the study:

|

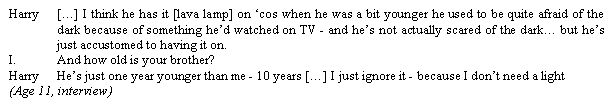

4.3 As the first born child in his family, Harry felt that he did not have a fear of the dark because he was used to sleeping on his own before he had a brother who shared his bedroom. However, he reported that his brother had needed a light when younger and this had now become routine and something which he, Harry, tolerated:

|

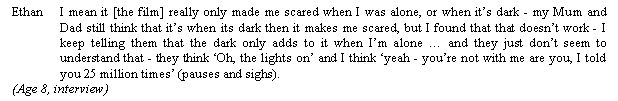

4.4 Ethan however felt that his parents wrongly focused on lighting levels when his concern at night was about being afraid because of a film he had seen which he had found scary at a later point, a fear which was accentuated by his sense of being alone in his bedroom:

|

4.5 The children in the study talked about their parents controlling the level of lighting in their rooms. The act of switching off a light to (re)instate night time darkness was reported as a simple matter of fact about what parents do:

|

4.6 The older children often reported that they took responsibility for switching off a bedside light, positioning this as a key moment in readying themselves to sleep. The bedroom light being on allows the child to linger on the periphery of the day-world, and switching it off, and hence introducing darkness (or partial darkness) into the room, is a step across the border that lies between the day-world and the night-world.

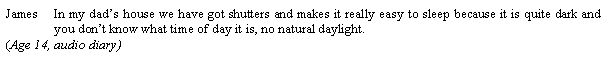

4.7 Far from lighting being an area of contestation teenagers were in complete control of their own lighting level, reflecting the greater control they had over the private space of their bedroom. Some aspired to achieving complete darkness:

|

whilst others modified the lighting in their room to reduce effort associated with switching the light off or on:

|

4.8 Light and darkness emerged as more significant for younger children, with children's requirements concerning this aspect of the environment of their night-world being met through institutionalisation of adjustments to the darkness or self-determined, but within the context of parents exercising their power to determine appropriate levels of light and dark. This is not to say that the children did not sometimes attempt to subvert this power by switching on a light when parents were elsewhere in the home, however such actions could result in being in trouble or at least parents intervening in this decision. In contrast issues of light and dark did not figure strongly in the teenagers accounts. Parents appeared to relinquish or handover control of the arena of the night-world to their teenager children in this respect.

Private spaces in the night-world

5.1 Differences between children and adolescents in relation to their night-worlds notwithstanding, the shape of these arenas for both age groups was strongly characterised by the notion of privacy and, of course, the activity of sleep (however long deferred). Although the domestic space of the household is sociologically framed as a private sphere: within the actual household individual privacy is a rare commodity. Living with others affords few spaces where an individual can be alone. For children this was even more the case as adult supervision and company lie at the heart both of the concept of care and of parent-child closeness in the home. Teenage life may involve attempts to secure more privacy and some of this is achieved through demarcations of space in the home such as a bedroom as a private space with restricted access. Other work has shown how bedrooms operate as spaces in which children and young people perform, practice and play with their identities (see McRobbie and Garber, 1976), in contemporary times utilising multi-media technologies to this end (Bovill and Livinstone, 2001). This was also the case for the young children in this study – their bedrooms were redolent with the materiality of various identities, including gender written into and on bedroom furnishings and decorations. For our purposes, though, we maintained a focus on sleeping as a bedroom activity. This focus stimulated reflections particularly from the children about private moments afforded by their night-worlds. Ben expressed this particularly poignantly:

|

5.2 An exchange about thumb-sucking elicited a similar account of time-out from demands:

|

5.3 Opportunities for these private moments of self were often identified as occurring just before going to sleep or as part of the process of getting to sleep. We defined this as the point at which the child enters deeply into their own night-world, a world which afforded children opportunities for an intimate and private relationship with themselves within which they can escape other demands as Ben recounts or just have time to think:

|

5.4 This privacy and solitariness resonates with contemporary constructions of sleep and nightime as quiet, private time. However it was very compressed in time, and did not extensively characterise our participants' experiences of sleeping. Recent work has shown how this construct of quietness and privacy has little in common with the actuality of sleep in the lives of adults who share their sleeping space with another person or who have night-time care responsibilities for others in the household (see for example Williams and Bendelow 1998; Hislop and Arber, 2003). However this is also the case for children and teenagers, albeit usually for different reasons. Not only is the space and time available to be private very limited for young people, once sleep descends it could well be interrupted in a variety of ways, a situation we explore in the next section.

5.5 As we indicated earlier, for the teenagers the decrease in parental regulation of their activity and the ensuing greater privacy available in their night-world afforded something quite different: opportunities to interact with friends using mobile phones or the internet.These opportunities were extensively taken up, with teenagers usually leaving the phone on all night 'in case' a text message was received:

|

5.6 The use of mobile phones to mediate social relationships is well documented (Taylor and Harper, 2001; Williams and Williams, 2005), and for many of the teenagers in this study one of the most common activities was a final contact with friends using their mobile phones. This utilisation of private times as times for interactions with friends stands in contrast to the younger children's experiences and valuing of similar solitary times as opportunities to be disengaged from the demands of interactions with others and instead enjoy time to themselves.

Actors and agents: populated night-worlds

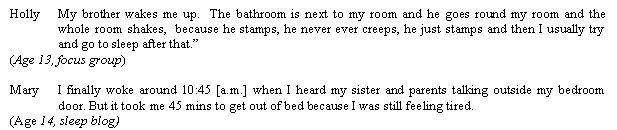

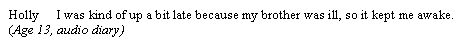

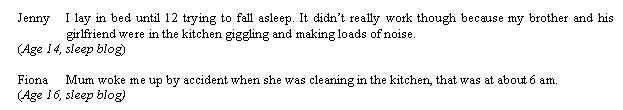

6.1 Parents and siblings figured as important actors in the night-worlds of both the children and the teenagers, albeit in different ways. For the teenagers, siblings and parents were often reported as disturbing their sleep both at night and in the morning for a variety of reasons. Such disturbances were generally unwelcome:

|

6.2 Household events such as a sibling being ill also featured in some night-worlds despite the individual being in their own bedroom:

|

6.3 The capacity to maintain a night-world as a separate realm from the rest of the household was also undermined for some of the respondents by the location of their bedroom in the household. Those whose bedrooms were near the centre of family activity reported hearing others in the house both late at night and early in the morning:

|

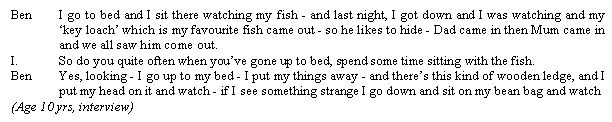

6.4 The children in the study took a more benign view of their parents' interactions with them at night, detailing night visits from their parents to check on them, rearrange them in their beds, retrieve them from bad dreams and sleepwalking, and take them to the toilet. These activities were known to the children, sometimes waking them in the process, and generally meaning that sleep was not entirely a solitary non-interactional time. In addition to parental visits to check and regulate the night world of the children, all the children in the study indicated that their night-worlds were also populated by a variety of soft toys and pets. Lee (2005) has written elegantly about these as transition objects, but here we want to simply think about them as other agents in the world of sleep. Toys and pets were cuddled in bed, talked to, watched and looked at in the space between the waking world and the sleeping world. Ben spoke eloquently about his pet fish which he kept in a tank on his side of his shared bedroom, recounting watching them both as a solitary action, and as one he shared sometimes quietly with his parents when something special happened:

|

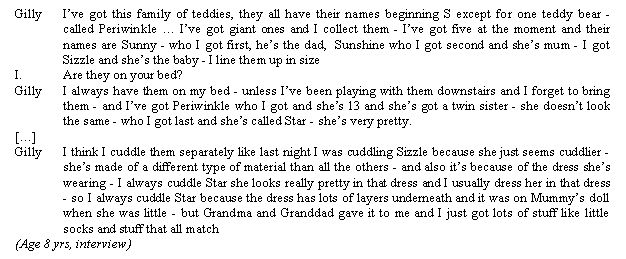

6.5 Many of the children also proudly listed large numbers of soft toys, and the visual data captured some bedrooms and beds crowded with cuddly objects. Gilly was particularly expressive about her soft toys, they were important inhabitants of her bedroom and took on many roles:

|

6.6 Night-worlds emerge as populated times rather than solitary for both children and teenagers. Intrusive agents in the night-world were problematic, but other presences were welcome and sought: friends in the case of teenagers, pets and soft toys in the case of the children. The presence of these co-habitants – virtual or material – enabled the children and teenagers to have intimate, close relationships unregulated by adult mediation, something which was treasured by both groups of respondents.

Continuities and extensions: day-worlds and night-worlds

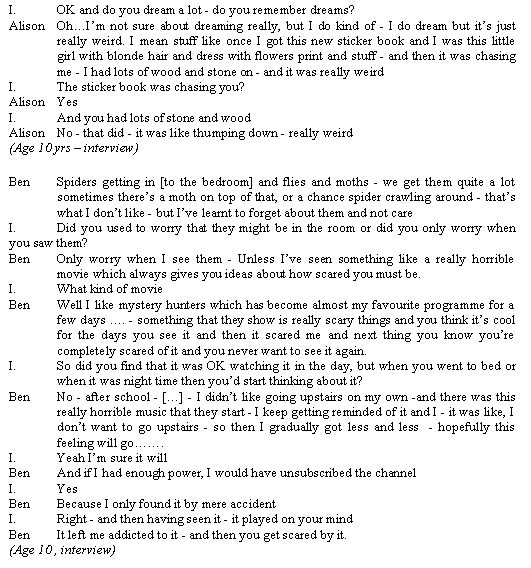

7.1 Although day-worlds and night-worlds can be constituted as separate arenas, there is little discontinuity between them: the activities and contents of day-worlds reach into individual night-worlds in the form of dreams and nightmares. Here we aimed to understand the ways in which dreaming linked day time and night time, waking time and sleeping time. Many of the children in the study recounted dreams with content which drew their wakeful activities and experiences into their sleep. The children often drew attention to the frightening content of these dreams, although they also recounted pleasant dreams. This drawing of the day into the night could incorporate events from the day, as in Alison's narration of a memorable dream, or could be the reappearance of ideas and day time fears as in Ben's dream:

|

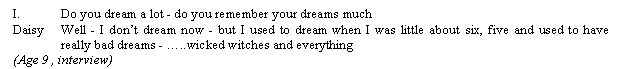

7.2 Dreams also created interruptions to sleep, leading to children seeking out their parents, switching on the light or sometimes being afraid to go to sleep. Dreams also had a certain sort of longevity: a recurrence of a previous dream or the persistence of the memory of a dream into the next day. Gilly talked of a dream she first had two or three years earlier, whilst Harry talked about a bad dream sometimes haunting him into the next day, banished only by playing football rather than thinking about it. Several children also used dreams as a marker of their growing maturity, leaving behind a younger past when they were more at the mercy of dreams and fears:

|

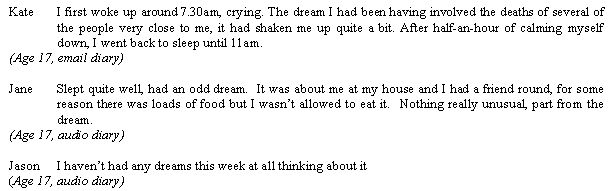

7.3 Dreams were seen by teenagers as intrinsically linked with their night-world and the appearance, absence and meanings of the dreams were often remarked upon in their sleep diaries:

|

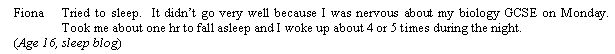

7.4 Continuities and extensions between day and night more often consisted of worries about school work and exams for the teenagers in the study. The focus groups and sleep diaries were completed during the GCSE and A level examination period and worrying about exams featured regularly in the diaries.

|

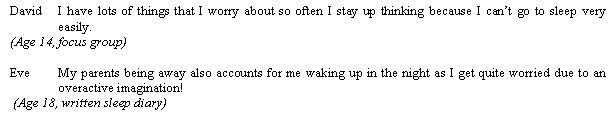

7.5 Examinations were not the only cause of worry, with several of the teenagers explaining in their diaries how worries kept them awake and delayed sleep:

|

Discussion

8.1 It is difficult to define what exactly constitutes the arena of the night-world, although we can identify elements of its composition. Although it is to do with sleeping, sleeping would seem to occupy only a small part of that arena. Nonetheless, the idea of sleeping, and in particular here the adult idea of sleeping, strongly orders this world for children. This is accomplished through regulation of interaction with others, changes in spatiality in the home, the generation of conditions of solitude and quietness, and the control of light and dark. In addition, adults seek to order this world and its various occupants through surveillance and monitoring, and paradoxically through that become part of the night-world itself. In the light of this, the notion of quietness and withdrawal in children's sleep begins to look somewhat more ideological than empirical.

8.2 For teenagers, the boundaries and shape of the night-world are rendered even more complex. If we take the concept we are working with here as being linked to sleep and private spaces, rather than to activity and public spaces, then again we can identify an arena in which norms of social interaction are different from other arenas. Specifically, the night-world is spatially located in the bedroom, but for teenagers it is not necessarily about solitude. Possessing the means to initiate or continue contact with people outside the domestic sphere creates strands of interaction which connect them to individuals in other places who may or may not be inhabiting their own night-worlds. What is key here is privacy and the opportunities which may be taken up to be in contact with peer groups away from adult supervision and intervention. Lee (1998) has developed a cogent analysis of how communication and media technologies circumvent and destabilise the mediation by adults of children and young people's engagement with the public world outside the domestic space.

8.3 So, what are the significances of making visible the shape and location of the night-worlds of the children and teenagers who participated in our studies? As we argued at the start of the paper, these are arenas of action, and in particular arenas which are shaped out of inter-generational interactions at a household level (Mayall and Alanen, 2001; Mayall and Zeiher, 2003). Through examining accounts of the creation of this arena in which sleep takes place, sleep is located more visibly within relevant material contexts. In addition, the ways in which sleep is located in an arena saturated with social interactions with parents, siblings, non-human and inanimate actors, and with friends who are not co-present is significant for extending the sociological gaze beyond the sleeping person.

8.4 The place of inter-generational dynamics in the configuration of the night-world and of sleep in the lives of children and teenagers requires more attention. In addition to this, there emerge interstitial spaces in which children and teenagers are afforded less mediated experiences of their lives where the usual inter-generational relationships that constitute their family lives are rendered less significant or at least less immediate (Mayall and Alanen, 2001). Children particularly recounted moments where they effectively enjoyed a relationship with themselves in the sense of being free from demands of others, having time to think, or indulging in pleasures private to them such as thumb-sucking or cuddling pets and soft toys. This is not to say that the night-world was a completely separate arena from those of the day-world. Dreams which became or were nightmares drew in daytime anxieties and experiences. Illness and upset pursued them into disturbed nights. Nonetheless, our participants expressed a sensuous pleasure gained from being in bed and from sleep itself.

8.5 Understanding sleep and its arena requires attention to other social orderings, to the dynamics of domestic life and to the distribution of power. In the lives of children and teenagers this has to be set within the potent and continuous production of this status and identity at both a micro- and a macro-level. Although we have not explored here other data which points to the macro- and ideological ordering of these arenas such as child care manuals, professional discourses, and the institutionalisation of night-time as a separate field to day-time, nonetheless preliminary reflections point towards the ways in which the constitution of night-worlds, and the management of its contestation, can be empirically investigated.

8.6 Whilst sleeping is a physiological necessity it is deeply embedded in its cultural and historical moment. Sleep is structured through society, and we would also contend, society is partially structured through sleep. Addressing age as a key ordering and its relationship to sleep in a sociological framework reveals a particular intersection. We also need to move beyond this to examine how age, class, ethnicity, gender intersect and are themselves produced at the site of sleep and in the arenas of night-worlds.

Notes

1 In the children's accounts we were not concerned with how right or wrong they were about what time they went to bed, although this is one of the moral dimensions which has been taken up as a normative issue and is strongly linked to particular British cultural notions of where children should be at certain times of the day or night, compared say to Mediterranean cultures. What we wished to understand in relation to the timing of bedtime was how time figured for the children themselves, how they utilised the naming of times to order and establish what going to bed involved and meant.

References

ALANEN, L. and MAYALL, B. (2001) (Eds) Conceptualising child-adult relationships London: Routledge Falmer Press.

BOVILL, M. and LIVINSTONE, S. (2001) 'Bedroom culture and the privatisation of media use' [online]. London: LSE Research Online. <http//eprints.lse.ac.uk>.

COFFEY, A. and ATKINSON, P. (1996) Making Sense of Qualitative Data Analysis: Complementary Strategies. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

GRAHAM, M.G. (2000) 'Sleep Needs, Patterns and Difficulties of Adolescents', Summary of a Workshop, Washington, DC, , Washington DC, USA: National Academies Press.

HISLOP, J. and ARBER, S. (2003) 'Sleepers Wake! The Gendered Nature of Sleep Disruption Among Mid-Life', Women, Sociology, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 695-711.

HISLOP, J., ARBER, S., MEADOWS, R., VENN, S. (2005) 'Narratives of the Night: The Use of Audio Diaries in Researching Sleep', Sociological Research Online, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/10/4/hislop.html>

HUTCHBY, I. and MORAN-ELLIS, J. (1998) Eds: Children and Social Competence: arenas of action. Falmer Press.

LEE, N (2001) 'The Extensions of Childhood: Technologies, children and independence' in Hutchby, I and Moran-Ellis, J (Eds) Children , Technology and Culture: the impact of technologies in children's everyday lives. Routledge

LEE, N. (2005) Childhood and Human Value: development, separation and separability. Open University Press

MCROBBIE, A. and GARBER, P. (1976) Girls and Subcultures in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds) Resistance through rituals: youth subcultures in postwar Britain. Essex: Hutchinson University Library

MAYALL, B and ZEIHER, H. (2003) Childhood in Generational Practice. London: Institute of Education.

MEADOWS, R., Venn, S., Hislop, J., Stanley, N. and Arber, S. (2005) Investigating Couples' Sleep: An evaluation of actigraphic analysis techniques. Journal of Sleep Research Vol. 14, No. 4, pp.377-386.

MORAN-ELLIS, J. (2006) 'Children's 'night-worlds' – civilising the tired body' Paper at RC53 Sociology of Childhood session, International Sociological Association World Congress, Durban, South Africa, July 2006.

TAYLOR, A.S. and HARPER, R. (2003) 'The gift of the gab?: a design oriented sociology of young people's use of 'mobilZe!', Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 267-296.

VAN DEN BULCK, J. (2004) 'Television viewing, computer game playing, and Internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school children', Sleep, Vol. 27, pp. 101-4.

VAN DEN BULCK, J. (2003) 'Text messaging as a cause of sleep interruption in adolescents, evidence from a cross-sectional study', Journal of Sleep Research, Vol. 12, p. 263.

WILLIAMS, S.J. AND BENDELOW, G., (1998), The Lived Body: Sociological Themes, Embodied Issues, London: Routledge.

WILLIAMS, S. and WILLIAMS L., (2005) 'Space invaders: the negotiation of teenage boundaries through the mobile phone', The Sociological Review, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 314-331.

WILLIAMS, S., LOWE, P. and GRIFFITHS, F. (2007) Embodying and Embedding Children's Sleep: Some Sociological Comments and Observations, Sociological Research Online, Special Edition. Volume 12 Issue 5, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/6.html>