Changing Social Class Identities in Post-War Britain: Perspectives from Mass-Observation

by Mike Savage

University of Manchester

Sociological Research Online 12(3)6

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/3/6.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1459

Received: 16 Oct 2006 Accepted: 7 Dec 2006 Published: 30 May 2007

Abstract

The idea that class identities have waned in importance over recent decades is a staple feature of much contemporary social theory yet has not been systematically investigated using primary historical data. This paper re-uses qualitative data collected by Mass-Observation which asks about the social class identities of correspondents of its directives in two different points in time, 1948 and 1990. I show that there were significant changes in the way that class was narrated in these two periods. There is not simple decline of class identities, but rather a subtle reworking of the means by which class is articulated. In the earlier period Mass-Observers are ambivalent about class in ways which indicate the power of class as a form of ascriptive inscription. By 1990, Mass-Observers do not see class identities as the ascribed product of their birth and upbringing, but rather they elaborate a reflexive and individualised account of their mobility between class positions in ways which emphasise the continued importance of class identities. As well as being a contribution to debates on changing class identities, the paper highlights the value of the re-use of qualitative data as a means of examining patterns and processes of historical change

Keywords: Qualitative Data, Social Class, Identities

Introduction

1.1 In this paper I consider how we can re-use qualitative data to examine change over time. It is striking that this is not an issue which has hitherto figured very prominently in the now considerable debate about the potentials and pitfalls of the secondary analysis of qualitative data (on which see Corti 2004; Hammersley 1997; 2004; Fielding 2004; Moore 2007; Silva, 2007, Thompson and Corti 2004). The current debate is focused around the extent to which re-use allows researchers to validate, qualify, or rework the findings of an original study: it therefore implicitly contrasts a 'then' time (that of the 'original' study) and a 'now' time (that of the re-study, i.e. the present day). There have been few attempts to look at different qualitative studies at several time points to allow researchers to examine trends over time[1]. This is interesting in view of the fact that this concern is probably the main driver for those who conduct secondary analysis of quantitative data. It is clear that over the past twenty years the strategy of delineating social trends by comparing different cohorts within one cross-sectional survey (as for instance in Goldthorpe 1980) has been replaced by the strategy of comparing results from comparable surveys carried out at different points in time (e.g. Inglehart 1990; 1997). The recent increase in commissioning of panel surveys, notably the British Household Panel Study, increases this potential of survey data to be used as a crucial tool for exploring trends even more (see Rose 2000). Yet, although the debate on the re-use of qualitative data has been conducted under the shadow of the secondary analysis of quantitative data, the issue of how we can use qualitative data to look at historical patterns of change has not been seriously posed.1.2 This deficiency is intriguing also because social and cultural historians of recent British history have also not shown much interest in considering how such data can be used in their own studies. Historians who have examined change in Britain rely mainly on textual or visual representations, supplemented by standard archival sources, usually from the public archives (e.g. Marwick 1996, Weight 2002; Sandbrook 2004). Even though we can detect a trend for historians to be more likely to conduct research on the post 1945 period (for instance, Black 2003; Ward 2001; Zweininger-Bargielowska 2001), these historians rarely engage with the popular narratives collected by social scientists – in the form of interview accounts, ethnographic reports, fieldnotes – as source material[2]. There are no attempts to champion a 'people's history' of the post war years – despite the fact that the potential resources for such a project increase dramatically as a result of the expansion of social science research on diverse underprivileged groups[3]. This is revealing, given that historians of earlier periods have developed remarkably subtle and interesting means of using 'social science' sources as historical data (e.g. Poovey (1998), Thompson and Yeo (1972), Rose (2001), Joyce (2003), Szreter (1993), Higgs (2004)). By the time we get to the post-war years, when social science begins to seriously expand in scale and scope, historians mainly stop using such studies as source material. Insofar as post-war social science studies are used by historians – and they usually aren't - then they tend to be seen as 'literal' accounts of the events they purport to study[4].

1.3 This paper is therefore a pilot exercise to see what might be gained through using qualitative data as a means of examining historical change, taking the particular instance of class identities in post war Britain as my focus. In the body of the paper I examine data from Mass-Observation directives asking their correspondents about their class identities in two different periods, 1948 and 1990. I show how the way that Mass-Observers wrote about class changes in subtle and revealing ways between these two periods. Whereas survey evidence appears to indicate relative stability in class identities, qualitative data suggests changes less in the class 'labels' people use (middle and working class, most notably) but more in the forms through which class is articulated. My paper begins with some methodological remarks regarding how we can use qualitative data to examine change over time. The second section of the paper explains why the study of class identities is particularly revealing. I then go on in the body of the paper to explore the nature of class identities in 1947 (Section 3), and in 1990 (Section 4). I pull out the ramifications of my findings in the Conclusion.

1: Methodological issues

2.1 A moment's reflection indicates that it is no easy matter to use qualitative data to explore change over time. When one conducts secondary analysis of survey research, one invariably gains access to some kind of codebook and a data file. Although there is rarely any contextual detail about how the research was conducted or formulated, the researcher can gain ready access to an abstracted sets of data collected at different points in time, which can be analysed very quickly, so that quantitative measures of change can be developed. By contrast, records archived by qualitative researchers have no common standard governing their format (although this is becoming less true for more recent deposits archived in accordance with ESDS Qualidata procedures). Typically, there is much information on the conduct of the study itself, such as correspondence with sponsors, colleagues and respondents, alongside the actual 'data'. Various fieldnotes, diaries, and papers are kept in differing states of organisation. Where in-depth interviews have been conducted - even when these are systematically filed - they are not amenable to quick analysis in part because they are not machine-readable (although this situation may change as a result of initiatives towards the digitisation of paper copy)[5]. There is no easy way of easily producing 'aggregate' findings, in the way equivalent to the quantitative researcher who can, within seconds, run frequencies on their data. More seriously still, the samples chosen for study by qualitative research vary enormously, and rarely (if ever) approximate to the kind of representative sample that allow quantitative researchers to report national demographic trends.2.2 The result of these differences is that most studies of social trends rely overwhelmingly on quantitative data. Consider the most authoritative volume on social trends in 20th century Britain, the edited collection of Halsey and Webb (2000). This contains 19 chapters covering diverse aspects of demographic, economic, social, political and cultural change over the twentieth century. Every one of these chapters relies upon data from surveys conducted at different time periods as the bed-rock of their analysis. Qualitative data is hardly used, even for those topics, such as the family, religious belief, crime, or health, where they might be thought to be essential. What we see here is a politics of knowledge akin to that discussed by Timothy Mitchell (2001) in his study of the production of social scientific knowledge in 20th century Egypt. He shows how the construction of various kinds of quantitative data is a central feature of abstracting, modernising, processes which produce forms of 'locationless logic', themselves part of the very project of forming, and governing, modern capitalist societies. The very idea that social trends can be determined from abstract indicators is a part of this process – and the absences which this data contain, about context, meaning, narrative - themselves become essential concomitant invisibilities around which abstract knowledge depends.

2.3 In order to provide alternative accounts of historical change, we can try to take advantage of the messy-ness of qualitative data. Rather than providing abstract knowledge, they can be read as relics revealing features of the research process itself (see Savage 2005a). This can be seen as part of Moore's (2007) argument that we should focus less on the issue of re-use, and more about how we use this data, much in the same way that historians do when confronted with disparate sources (see also Bishop 2007). We should not frame the issue of re-use in positivist terms, where we focus on how we might consider how we might validate or disprove the arguments made by qualitative social scientists by going back to their data and showing if they misinterpreted their own work. Apart from any other considerations, the kinds of fieldnotes left behind by such social scientists simply are not of the kind which (except in very rare circumstances) would allow later researchers to dispute or confirm original interpretations. Nor is it possible to treat the data left behind as 'raw data', which can be used in ways not intended by the researchers themselves: the purposive nature of qualitative research would make such an enterprise highly problematic.

2: Class identities

3.1 In pursuing this project of using qualitative data to provide a distinctive kind of historical account, I will take the specific case of class identity as my focus. I take class identity not because it is necessarily the most important popular identity to study but because it raises particular strategic issues regarding the re-use of qualitative data which have broader ramifications. This is for four reasons. Firstly, the claim that class identities have waned is central to much contemporary theory, so that our arguments derived from using qualitative data can readily be used to engage with such theoretical arguments. All dominant accounts of socio-cultural change draw on some versions of the claim that class identities have declined in recent decades, as the result of the cultural fragmentation associated with individualisation, de-traditionalisation, post-modernisation and the like (see variously Beck 1992; Giddens 1991; Bauman 1998; Castells 1996, and the discussion in Savage 2000). Thus, our findings about class identities will allow us to speak to these kinds of epochal prognostications.3.2 Secondly, by focusing on class identities, we can compare the findings from qualitative data with those derived from quantitative research. This is because numerous survey researchers have inquired about class identities since the 1950s, so that it is possible to explore the relative strengths and weaknesses of secondary accounts derived from surveys compared to those from qualitative sources. Survey sources indicates that from the 1950s to the current day, less than 10% of people refuse to give themselves a class identity[6]. Furthermore, and unlike many nations, there has been little decline in the proportions of people claiming to be working class. Whereas in most nations, middle class identities now predominate, usually to an overwhelming degree, around two thirds of Britons indicate that they are working class in response to survey researchers, a proportion which has changed hardly at all over a fifty year period – despite dramatic shifts in the occupational structure. It is hence a viable topic to explore whether qualitative data comes to similar conclusions.

3.3 Thirdly, we are fortunate that qualitative researchers have asked about class identities in some form or another since the 1940s. There are several projects located either in Qualidata or Mass-Observation, which can be used to explore class identities at different time points[7]. In fact, class identities are the ones that researchers have systematically inquired about over the entire post war period, so that we can indeed relatively easily compare data on this topic over a fifty-year period. Of course it is a matter of interest in its own right that researchers did not ask explicitly about ethnic, gender, sexual or indeed most other kinds of possible identities until the 1980s, but this is an issue, which goes beyond the bounds of this paper.

3.4 Fourthly, given my concern to make the research process itself the object of inquiry, so that we learn not only from the data with respondents but also the practices of the research itself, then there are a number of ways in which the studies themselves intersect with issues of class identity. If we take Bourdieu's (2001) contention that there is a fundamental divide between what he calls the 'scholastic point of view' – concerned to define abstract knowledge through its distance from everyday life – and that of popular culture defined by the compulsion of the routines of everyday life, and that this division is a powerful structuring force in contemporary class relations, especially through the role of cultural capital in reproducing middle class privilege, then we can study how the practices of academic research themselves might be implicated in changing forms of class relationships and identifications. We can explore how relationships between researcher and researched are themselves class relationships which may give rise to telling kinds of class identification which we can now interpret. Substantively, we can also connect issues of class to Giddens's argument about the 'double hermeneutic' - how do the ideas and concerns of social scientists themselves affect popular culture itself. In what situations can various kinds of people draw on the kinds of knowledge being produced about them in the name of academic social science as resources that they can use to mobilise their own identities, and what might this tell us about the relationship between culture and class? Similarly, there are also interesting parallels with Strathern's (1990) interest in how making the implicit explicit, how seeking forms of transparency, have the effect of changing the object of study.

3.5 The study of class identities using qualitative data is therefore highly pertinent. In what follows I contrast the accounts given by Mass-Observers to a directive asking them about their attitudes to, and identification with social class in two different times: 1948 and 1990. The directive was a distinctive research tool developed by Mass-Observation from 1939. From 1937 letters in the New Statesman and articles in the press encouraged people to write to Mass-Observation to enrol as observers who initially were asked to keep detailed 'day diaries' which they sent into Mass-Observation (Hubble 2006: 118). From 1939 they were asked to write down their responses to a set of Mass-Observation questions. The early directives are relatively formal, in that observers were asked to write on a sheet of paper, headed with their identification number, their age, sex and occupation (see further, Kushner, 2005, Chapter 4). Responses to these directives vary considerably in number, and it is not possible to readily ascertain which kind of observers responded, and which did not, to any one directive. Having reached a high point during the Second World War, these directives became steadily less frequent thereafter, and the last directive was sent out in 1955. Following the University of Sussex's acquisition of the Mass Observation archive, it was subsequently decided to develop a new series of directives from 1981, with a new panel established, also through asking interested people to write to Mass-Observation following letters and articles in the press.

3.6 It is from these two different waves, that we can compare the letters written 42 years apart. The Directive in September 1948 included the questions:

Do you think of yourself as belonging to any particular social classThe Directive in Spring 1990 asked:

If so, which?

Why would you say you belong to this class?

Give a list of ten jobs you consider typical middle class and ten jobs you consider typical working class

Are there some major divisions in your own environment – class, race, gender, religion, 'culture' etc – that invite comment and are typical of contemporary society?

What does it mean to be 'middle class'?

What does it mean to be 'working class'?

Do terms 'upper middle class' and 'lower middle class' correspond to anything in your experience? Please give examples.

Can you give local instances of snobbishness?

3.7 It is clear that these Directives ask their questions in different ways, and we cannot expect equivalent replies. However, once we recognise that we are not seeking to obtain abstract replies as responses to a standard question, and treat it as a matter of interest to see how question wording itself changes, then this does not pose any insuperable problems. Substantively the analysis here for 1948 is based on detailed notes on 68 women and 107 men, sampled in order in which they appear in the alphabetical files. For 1990 I have looked at 24 men and 43 women (all those with surnames starting with A and B). This is therefore not a systematic reading of all the responses, but equates to a sample of around 10% of responses in both years). This strategy faces the objection that my use of the sources is partial in not sampling every letter, and does not do justice to the qualitative nature of the study itself. This is an objection with considerable force: nonetheless, there is equally a danger that seeking to read and present summary findings of several thousand responses, which are not part of a representative sample and hence not likely to improve the reliability of the findings, may offer false security[8]. Here, my preference has been to rely on a strategy of sampling which is rather akin to that of theoretical sampling as discussed by Glaser and Strauss (1968) where one conducts interviews, or in my case reads letters, up to the point that the researcher feels that little more is being gained by reading additional amounts. This strategy has the advantage of taking seriously Moore's (2007) emphasis on seeing the re-use of qualitative data as being a kind of original qualitative inquiry in its own right.

3: Mass-Observation and class identities in 1948

4.1 In 1948 Mass-Observation had just completed its first decade, but it was already in steep decline. Its heady days of the later 1930s, when it developed an unusual surrealist ethnographic approach to everyday life had already given way in the war years to a more established interest in studying popular opinion for the benefit of government (Jeffrey 1999; Hubble 2006; Kushner 2005). After the war it struggled to find a new role for itself. Its main hope lay in marketing research, where it increasingly came up against the power of the new opinion polling companies who saw its lack of representativeness as fatal to its claims. The post-war directives sent out to mass observers indicate the uncertain ambitions of Mass-Observation in this period, with requests for focused marketing information often appearing in the same directives as broad ranging inquiries about everyday life. So it was in September 1948, when the Mass-Observers were asked a series of almost sociological questions about their views about class (as reproduced above), followed by questions about whether it was indecent for couples to make love in public, and then their views about Christian Dior's New Look which, with its longer dress sizes was sweeping the fashion world. The three faces of Mass-Observation were thus simultaneously on display; its interest in academic social sciences; its surrealist interest in quizzing the boundaries of public decency; and its attempts at market research. The Mass-Observers themselves seemed to take this mixture in their stride: nearly all those who replied attempted to answer all three questions, although with varying degrees of enthusiasm and interest. And indeed there was remarkable unanimity: pretty much everyone was appalled when couples made love in public (though quite a few wondered what exactly this coy phrase meant: kissing, holding hands, intercourse, or just looking fondly at each other?), whilst the New Look commanded widespread enthusiasm, especially from women, though there was the occasional grump that it was anti-patriotic because it required more cloth than shorter skirts and hence would lead to clothes shortages.4.2 And so it was too with the questions on class. In part, the uniformity here was due to the remarkably selective nature of the Mass-Observers themselves. Those writing in response to the Directive had always been a predominantly middle class group, though before the Second World War there was rather more working class involvement. By 1948 those writing were nearly entirely comprised of professionals, senior clerks, and middle class housewives[9]. Only 1% of male observers had a manual occupation, and none of the women were either manual workers or reported being married to a manual worker. It is thus not entirely surprising that so many of them claimed to be middle class when asked if they thought of themselves as belonging to a class.

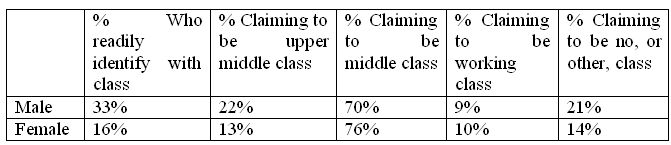

| Table 1. Class identities of Mass-Observer Sample, September 1948 |

|

4.3 Three quarters saw themselves, either voluntarily or when pushed, as middle class, with a substantial minority of these seeing themselves as upper-middle class, and only 10% saw themselves as working class. These identifications clearly reveal how atypical the sample was for the British population: Martin's (1954) survey, conducted in 1950, suggests that only 1.4% of the population saw themselves as upper middle class, and 50.6% as middle class[10]. Clearly, Mass-Observation seems to have become the haven for the middle class, and especially the educated middle class. However, I have emphasised that we are not interested here in the a typicality of these responses so much as the ways in which class is talked about, in this case by predominantly middle class identifiers.

4.4 Geoffrey Gorer (1955: 23), in one of the first ever-national sample surveys of the British population, argued on the basis of survey data that 'there is no question that class membership is the most important facet of an Englishman's view of himself as a member of society; and the class to which he assigns himself is nation-wide'. Gorer's insistence on this point seems rather strange since he had no information on respondents' strength of class identification. This provides an excellent example of how Mass-Observation records offer a more subtle view. In fact, only a minority identified themselves confidently and readily as belonging to a class[11], but the hesitancies are telling in underscoring the power of a particular conception of the social order, one espousing the moral power and rightness of the professional middle class. A key feature of these values was ambivalence to the very language of class itself. Numerous observers contested the value of talking about class, though in terms which indicated that they actually had a clear sense of themselves in the social hierarchy. At times, such accounts were simply an initial refusal to identify as members of a class, followed by a willingness to place oneself when pushed.

I hate class distinctions and do not think any definite lines can be drawn between social classes, but if there has to be a division, I consider myself to belong to the upper middle class (2-195)

4.5 This kind of account shaded into the view which in one breath denied the relevance of class, before in the next breath, claiming a clear social identity.

I would like to think of myself as not belonging to any particular social class. …. If one recognises the professional middle class as an entity, I was born into it. None of my forbears has had the initiative to become anything other than a soldier, doctor, lawyer or clergyman (9-458).

4.6 This is a very revealing formulation. The hesitancy in describing class comes from seeing the professional middle class as 'above' class, as a category which in some ways overrides class distinctions. The reason for this lies in the way that the professional middle classes identified themselves as a 'cultured' class, with this culture being seen as elevating them above the mundane and practical business of class (see also, McKibbin 1998: esp. Chapter 3).

Purely financially I come under working class, but keep company with anybody, mainly upper middle class. My mentality is (pardon me) intellectually above "class". So I can't class myself' (11-1814).

4.7 To openly identify yourself as a member of the professional middle class would, in a sense, be to indicate a degree of vulgarity that might in fact put a question mark around one's membership of that class. So it is, that many of the more eloquent Mass-Observers seem to register hesitancy about class in the very same breath as stating an apparently clear and unequivocal social identity

I strongly resent the emphasis that is placed on differences of class and all the snobbery and inverted snobbery that is associated with it, but however reluctantly I must admit that I do consider myself as belonging to a particular class, though I don't stress it and certainly don't consider my class superior to any other. … I have a university degree and I have certain standards of security which I think the middle class hold out as an ideal, even if they don't attain them, standards such as owning a house, with an amount of space in it which is more than the working class would consider reasonable, such as having sufficient savings to provide for emergencies, to enable one to change jobs, to remove across the country, to educate one's children on a higher standard than the working class would consider necessary… work with the brains rather than with the hands (13-368).

4.8 This woman, the wife of a University lecturer, at one moment resists the idea that she is better than anyone else, before going on to precisely identify her superior standards: an interesting way in which one disavows social superiority through the same process of affirming it. It is also this which explains why so few of the sample saw income or occupation as being the defining feature of class: for if this were so, they would be judging themselves by crude, material or monetary criteria, rather than by the cultural standards that they held so dear. The further implication was that the professional middle class was a class apart. As one man put it with disarming honesty

I maintain two very distinct standards – a wide tolerance for the mobile[12] – and a very different standard for those who are, or should be, my equals. In fact a "gentleman" does not display his emotions in public, any more than he appears drunk in public' (23-055).

4.9 The professional middle class here are almost a caste apart, and even those who rise into its ranks cannot be treated as a real, bona fide, member. But we also see in this account how claims to membership of this group rested on a striking abnegation of agency on behalf of the middle class itself. In the quote above, this is hinted at by the pride in not displaying emotions, in only displaying etiquette as a kind of collective code announcing latent membership of the group as a whole. Membership of this class is seen as ascriptive, as something which you are born into, and which one cannot claim as an individual reward. One is middle class not through one's own efforts, aptitudes and skills, but through claiming membership of a social group through social ties of family, education, friendship and the like over which one has no direct control. Hence the insistence that middle class status was handed down by one's parents, and extended family more generally. One engineering draughtsman argued that he was middle class because of his family environment

My parents were able to give me a public school education and being the son of a naval officer had always to be an example to him' (40-4507).

I try to eliminate all class distinctions from my social life… however I suppose I have been brought up with a middle class outlook as…. For the most part of ten years my father has been a regular army officer. (40-4519)

4.10 As one young women, an art student, explored the role of her family in identifying with class

Actually, class is not a subject I give much thought to…. However when the subject has come up, mammy always said we were professional class… of course I think of some people as "common" but these always seem to be awful anyway…. It's difficult to say why I think I belong to this class, but presumably it is because daddy is a mining engineer and all my recent ancestors on both sides of the family were either doctors, or mining engineers, excepting mammy's father who was a vetinary surgeon and amateur steeplechaser' (15-4343).

4.11 Another housewife talked about her upper middle class identity in the following terms

Because my forbears have been brought up Christian gentlemen for many generations…. Because one of my grandfathers was a church of England parson, and the other the headmaster of a private school, both were at Cambridge, and because my father was scholar at Charterhouse and Trinity College Cambridge, and a wrangler' ((7-2003)

4.12 Every one of these criteria celebrate conformity to certain norms and standards and announce that the upper middle class identity is dependent on doing things 'correctly', conventionally, and in an 'accepted' manner. The widespread identification of an appropriate education for middle class status is also revealing. It might be thought that invokes some claims to individual achievement, but in fact what nearly always matters is the type of education one has, not whether a high level of distinction was achieved in qualifications (for the only exception, see 7-2003 above). Not a single Mass-Observer mentioned the class of degree they had, or the number of examinations they had passed: what mattered was the kind of school they went to, and having a university education of any kind was a badge of a middle class, and usually professional middle class, identity. Those observers who talked more fully about education saw themselves not as agents, as people who did especially well, but as the recipients of the benefits education could bestow. A student said he was upper middle class since 'when I conclude my studies, I will be fitted for a job which will put me in this category' (40-4597).

4.13 Identifying oneself as middle class hence involved not making claims about one's individual distinctiveness – your skills, talents, achievements – but was ultimately about showing how you belonged to a social group through ties of birth, through having appropriate manners, and other social ties. Numerous respondents talked about the distinctive culture which they had, which were often seen as particular kinds of habits, forms of speech, modes of address and dress, which ultimately proclaimed people to be bearers of a class identity.

The way I dress, by my interests, by my tone of voice, manner of address, subjects of conversation' (23-836)

4.14 This is very different from those who few people who did espouse a working class identity. Consider these examples

'As a worker with hand and brain who has carved his own way from the handicap of being left, an orphan at 10 years of age, served an apprenticeship at the printing craft and climbed the ladder after an absorbing life of "fight"' (21-4658)

'In my own opinion, anyone who works for a weekly wage, irrespective or remuneration belongs to the working class and even although my own wage would qualify me as middle class financially, I am a tradesman and therefore consider myself working class (26-4584).

I work for a living - it seems to me that anyone doing a job of work for his living is working class and anyone who has the means of living without having to work is very lucky (30 – 4509)

4.15 What we see here is that claiming working class identity is a means of individualising one's identity. This is especially marked with the first case, a process engraver, who claims a record of individual achievement as part of his working class identity. Yet the same motif is present, in more limited ways, in the third case where being working class is a means of emphasising that you have to work for your living and are hence necessarily constructed as an agent who cannot get by on unearned income. The second quote indicates individuality of judgement, where a working class identity is a means of showing that he is able to think for himself and come to his own idea about where he should be 'placed'.

4.16 We can see how middle class identities were both powerful yet also inarticulate: they depended on being implicit and taken for granted. They invoked certain kinds of relational judgements. Above all, the working class was a key reference point, a class always present in the minds of the middle classes. McKibbin argues that during the inter-war years the working class became the 'other' which allowed the middle classes to define themselves, and this defensive identity can readily be found, at times with some virulence, with the Labour government being seen as the enemy of the middle class[13].

I object intensely to the term "working class" judging by the way productivity in certain industries has fallen it is a misnomer. I consider the professional classes usually do more work than the so-called working classes' (4-1587)

'I went to public school, have never been short of the necessaries of life, and do not regard myself as a member of the working class' (35-2002).

'Although definitely not class conscious, I usually refer to any form of manual worker or uneducated person to a class apart from myself, which I generally term the working class' (41-4389).

4.17 This opposition was more generally thought of as representing the difference between brainwork and manual work. The idea that the middle classes worked with their brains, and hence were more intellectual, cultivated and superior to the working class runs very deep for many of the Mass-Observers. This emphasis on intellect and brainwork was also used against the upper class, as a means of emphasising the unique position of the educated middle class.

From a materialistic point of view, I would place in the middle class. Whereas we do not live in a large mansion with a staff of servants, have a "Rolls Royce" and mix socially with "country folk", we possess a house plus one acre of garden, two cars, and enough money to give us a good annual holiday at a first class hotel. This type of living could hardly, I think, be called that of a working class family' (3-4094).

4: Class identities in 1990

5.1 The evidence we have considered therefore indicates the power of a certain kind of middle class identity which refused to own up to itself as an identity and which was consequently the more potent. Let us now move forward 42 years, to examine the responses to the Mass Observation directives on 'social divisions' (detailed above). Although the questions were somewhat different from those asked in 1948, correspondents were nonetheless being asked to elicit information in a similar way. Like the earlier period, the sample was unrepresentative in being predominantly well- educated, female, elderly, and middle class[14]. The Directive did not ask correspondents to identify which class they were in, and hence it is not always clear which occupations the Mass-Observers had, as in 1948. However, if we focus on the form of the letters, a number of intriguing similarities and differences are revealed in what might be termed 'narratives of class'.5.2 As in 1948, most identify as middle class, and large numbers continue to be ambivalent about placing themselves in terms of class. The Mass-Observers are hence not representative of the population, but need to be seen as exemplifying a particular group of literate, articulate, generally middle class, writers. In this respect, they are rather similar to the Mass-Observers of 1948, however, we can detect a profound reworking of the style, the form, in which the Mass-Observers wrote about class. To introduce these differences, I extract three long statements, taken largely at random from those I have looked at. I also include further quotations from other Mass-Observers to substantiate the points I elaborate.

5.3 Let us consider the three extended cases

1) I am close on 59 now and I feel that no matter what I have achieved I might well have done better had I not been dogged by a complex about my working class background, a very basic education, and a perceptible Midlands accent…

Son of a small trader...

I was ill at ease…when invited to the home of a girlfriend who lived in a wealthy quarter of Wolverhampton. I was there for lunch, and while I was quietly confident my table manners would stand scrutiny, I was disconcerted to find a linen table napkin rolled in an ivory ring on my side plate. It was my first encounter with a napkin and while I knew it should be laid on the lap and not tucked into the shirt collar I could not think what to do with it when the meal was finished. It worried me greatly and finally I laid it nonchalantly on my plate in a crumpled heap….

Classes? Money makes people what they are – those with a lot, those with little and those in between with neither too much nor too little (B1654)

2) 'first preliminary jottings on this topic have revealed what a difficult subject it is; so many blurred edges, so many emotive connections….

So I just propose writing in essay form, using your suggestions as guide points

'I'll start by looking at my own life, past and present, and comment on any social divisions that spring to mind. Even in my own (extended family) I 'feel' there are divisions, caused by achievements in some cases, money and/or education in others

'my working life has been much more ordinary, and mostly I've just been 'a housewife' – married to a draughtsman as lacking in ambition as I am, I seem to have positioned myself on a very low rung of the social ladder'.

'What class do I think I belong to. It would be a hard job trying to define my position according to my family background – my relations include such different characters. The one brother, in particular, who is on several boards of directors…. That's at one end of the scale, - at the other, our own youngest son, unemployed and with a yen for a somewhat bohemian lifestyle…. All a bit of a mixture. Forget my family and judge me by my friends and associates, but it still confusing – several classes represented… what about my education? Now here is a puzzling fact – I was the only one of a family of five to receive private education …. In fact my brothers and sisters have without doubt made more social progress than I have. I think the definition I like best is to link my social status with the area in which I live. This is the area my husband and I have chosen and in which we feel most comfortable and secure… this is the level of society that suits us and I suggest that to some extent one does choose the stratum of society to which you are most suited.

'the one thing which annoys me is terms like "social class A B C1". (A2168)

3) 'When I am thinking about stereotyping I want to get out the way of the last paragraph of your checklist….. I am so terrified of stereotyping – and of being considered racist – that I am adamant there is not such thing as a national characteristic

In London 'class and race were the divisions and there wasn't really a great breaking down of either, only minor ones'. Class has always been significant to me: born the child of a white-collar worker in London dockland, a working class Tory of the bluest type, a royalist, a snob. That was my father, though I loved him and he had many attractive qualities.

'I rose, through education, to being middle class in my profession and in my leisure pursuits – that is the way I define class'.

To sum up, I believe that British society is class ridden, with money being the basis for this. In Britain money buys a better education, leading to better job prospects and power in whatever sphere (B1533)

5.4 In comparison to the earlier accounts, a number of striking differences are evident. Firstly, in 1948, answers were often terse and to the point. By 1990, extensive narratives were often provided (these examples above being taken from much longer accounts). It is more difficult to extract gobbets from the letters than for the 1948 cohort. Class proves to be a powerful hook for hanging stories on, in the way it was not in 1948. The reasons for this shift are complex. Mass-Observation in 1948 was still fighting its battle with nascent survey research companies about the best way to conduct market and opinion research, and was hence still interested in the content of what people said. It mattered whether people liked Dior's New Look or not. By 1990, this was a battle which had been won by the survey researchers, and the correspondents also seem to recognise that what is interesting is not their class identity (which could be given quickly, as they mainly were in 1948), so much as how they talked about class. And, even though they were not asked to, several mass observers provided autobiographical accounts, sometimes stretching to ten pages or more, The way that questions on class elicits life narratives bears comparison to Savage et al's (2001) research on class identities in the North West in the later 1990s. Savage and his colleagues discuss how common it was for respondents to interpret a question on their class identity in autobiographical terms, in ways, which had no counterpart when respondents were asked about other identities. This point is interesting to reflect on in view of the argument that class identities are waning in importance. The fact that people seem willing and able to write more about class is not obvious evidence for its declining salience.

5.5 A second difference can also be discerned, linked to the first point. The 1990s respondents draw upon a series of public repertoires around class: the 'essay form' is invoked, market research categories are mentioned. There is recognition of the politics of stereotyping (one shouldn't do it!) and the powers of classification itself. These concerns are mainly absent for the 1948 grouping. If the power of class for the earlier generation lies in its un-stated quality, it is now the explicit narratives and positioning which takes place in the name of class which are evident. Talking about class is a means of connecting personal narratives with public repertoires. In 1948 Mass-Observers rarely make reference to ideas of class, or indeed to any social scientific ideas or concerns. The only exception is that a sizeable minority have access to Freudian ideas which they occasionally introduce in writing to Mass-observation. By 1990 this 'double hermeneutic' in Giddens's phrase, is much more marked, as respondents recognise that social scientific ideas are part of their world. Some other examples, all elicited in response to this question, can readily be given

This is a MO[15] of enormous scope. Because it emanates from a university, one imagines one is expected to produce something akin to a dissertation on social and class matters, with appropriate research context

… as I have a degree in sociology, I suppose I should have a clear picture of what the terms middle class and working class mean, yet even among academic sociologists one finds, if not large differences of opinion, at least differences of definition. …. One lecturer, of the functionalist school, warned us that we should not confuse economic class with social status

'Mary Daly, in her book Gyn-ecology, suggests that the setting up of divisions or barriers is typical of patriarchy, so I am always reluctant to fit my thinking into what, tangibly and socially exists, circumscribing, nay defining my life

5.6 Talk about class is therefore laced with class discourse, and respondents use class talk reflexively to show their sophistication - very different to the Mass-Observers of 1948 who saw talking about class as a sign of vulgarity. The ability to engage in 'class talk' is itself now a means of making a statement that one is 'knowing' about the subtext associated with class.

5.7 Thirdly, more specifically, we see a reworking of the relationship between family and class. Class for the older Mass-Observers was primarily a product of family lineage over which they themselves had no control. Moreover, the family belonged to a class in a straightforward way, with little or no reference to different family members being in different classes so that families were 'stretched' between classes. For Mass-Observers in the 1990s, however, the relationship between families and class was constructed in a very different way, since families were often constructed as comprising members from different classes. Correspondents were much more likely to trace their movement between different class fractions within the family, so that the correspondent could emphasise their 'liminal' or 'ambivalent' class positions vis-à-vis other family members. This again strikes chords in Savage et al's (2001) research where the same kinds of hybrid family histories were often emphasised. This again, appears to be a means of allowing the correspondents to refuse a unitary class position, hence making a statement to those who 'classify'.

5.8 Fourthly, it is also interesting to note that the 1990 respondents all link their discussions of class to those of specific places. Respondents very rarely mention a particular named place in 1948, and where exceptions exist, they mainly comprise references to regions as a whole. By the 1990s, references to place are related to claims to class identity, and indeed one correspondent even explicitly states that their class identity is related to their choice of residential place. This attention to place appears to be linked to a sense of the fluidity of identity, and the ability of people to make some kind of choice. Other examples of this reference to place can also be found.

I was born in a (very) working class area and to a working class family and – by virtue of marriage and native intelligence – have been translated into the middle class. The end result is a hybrid; I feel comfortable with neither group and in fact often find I dislike both working class and middle class manifestations equally (B1224)

5.9 Fifthly, and drawing on this last point, we see how class is hence inscribed as part of an individual identity, albeit one which is fluid. Compared to the earlier Mass-Observers, the accounts in 1990 are much fuller, more confident, and placed more in terms of the individual's experiences – of not knowing how to use a napkin, being a housewife, rising to a middle class job. Class is presented as a matter of agency, rather than as something handed down, something which anchors an individual's biography in a larger frame. Hence, we can see how the kinds of individualised identities that have been discussed by social theorists require benchmarks of class as a means of measuring change. Hence, although there is considerable ambiguity about how people define themselves with respect to class, the sources of ambiguity are very different to those of 1948. In the earlier year, class is something which is un-stated, and correspondents do not like to talk about it. By 1990, they are happy to talk about it, in ways which emphasise their hybrid class identities, and which uses class as a set of external benchmarks around which they can announce their own individuality.

Conclusions: Understanding changing popular class identities in post-war Britain

6.1 Let me begin with the important caveats. This paper explores change between 1948 and 1990 using a sample drawn from correspondents to the Mass-Observation Archive, which as I have emphasised do not constitute a representative sample of the population. In order to draw general conclusions from these biases we have to make a positive virtue of the skewing of the sample so that we can interpret the accounts as indicative of middle class – broadly defined – identities in these two periods. Even more problematic is the fact that we only have two time points. In such a situation it is tempting to read the accounts as symptomatic of a broad period, rather than as the result of a specific conjuncture. Thus, the kind of ambivalent professional identities I explored in 1948 might be the specific product of middle class defensiveness in reaction to the post war Labour Government, with its perceived policy of aiding the working class[16], rather than symptomatic of mid twentieth century Britain more broadly. In a similar ways the kind of backward looking, reflexive accounts of the 1990 Mass-Observers could be seen as arising out of the dog days of Thatcherism, its energies spent.6.2 Given these concerns, this paper is an invitation to further research, reflection and debate. I hope that this paper has indicated that this broader project is eminently worthwhile, since even with its limits, a number of substantial points can be emphasised in conclusion. In understanding change and continuities, there is a difference according to whether we focus on form or content. In content terms, there is little change: most people define themselves as middle class, though generally ambiguously and ambivalently in both periods. Mass-observers rarely announce a clear and unambiguous class identity and wanted to announce their identities in altogether more coded ways.

6.3 However, this apparent constancy of content looks very different when we examine the form of the letters. The meanings of class identity rest in their latent, ambivalent, and opaque character, the way that they reveal as well as conceal. In the earlier period, ambivalence arose from the feeling that 'one does not talk about class', whereas in the latter, they arose from the concern to articulate hybrid class identities, where familiar class labels are reworked and 're-traditionalised' as they are drawn on by Mass-Observers to mark their mobility and individuality. I have stressed that this concern does not mark the end of class identities, because reference to class is still required to define the benchmarks around which individuals move. We can thus see that those social theorists who define individualisation as marking a break from class misconceive the key processes at stake. Instead, I have argued for an interpretation of change in which there is no 'break' with the past, but rather a deepening of old identities through the same process by which they are re-worked.

6.4 A key aspect of this deepening is people's increasing awareness of class as a political label, so that they are keen to position themselves not only with respect to other classes, but also to the labelling and classification process itself. This point explains my concern to use qualitative data to explore how the practices of research themselves are part of the very trends that we need to unravel. In 1948 Mass-Observers dis-identify with class because of their concern to emphasise their 'cultural' superiority where this is taken to be defined by deportment and taste. In 1990, by contrast, middle class, literate, Mass-Observers are more confident in positioning themselves with respect to various ways of narrating class, and use such forms of narration as a means of criticising assumptions about cultural superiority. Contemporary moral economies of class are thus doubly positioned, in which concerns to define class through differentiating oneself from others is mediated (in a literal sense) to the proliferation of discourses of class. Methodologically, therefore, we need qualitative sources to allow us to excavate these ambiguities, since it is the form, rather than the content, of class talk which is important. Arguments about class identities based on survey sources will almost inevitably miss important ways in which the forms of class narration can change.

Notes

1 The main exception I am aware of is Liz Stanley's (1995) prescient study of attitudes to sex in the post war years which uses different Mass-Observation surveys.2 There are some exceptions, such as Mark Clapson (1998).

3 This is of course a sweeping generalisation, which needs qualification. However, even in the area of oral history, where there has been the most concerted effort to gather popular testimonies, there has only been very limited use of such resources in most accounts of socio-cultural change.

4 Consider for instance, the way that Goldthorpe and Lockwood's affluent worker study is read literally by Weight (2002: 378), and Marwick (1996: 157). There are welcome signs that this situation is changing: see the comments by Black and Pemberton (2004: 5): 'the ways in which political science, economics, sociology and cultural studies have fashioned interpretations of the meanings of this period ought to be of at least as much interest to historians as the veracity of the interpretations themselves'.

5 Qualidata is currently digitising some of its material and making it available for download, though this process is expensive and time consuming. In fact it is uncertain how far digitisation will proceed given possible ethical problems in reproducing testimony in reproducible format.

6 Though significant proportions only define themselves in terms of class when pressed by survey researchers to choose a class identity. See the discussion in Savage (2000) 34f.

7 In Qualidata, these are specifically, Bott's 'Family and Social Network' study, 1951-6; Goldthorpe and Lockwood's, 'Affluent worker Study' 1962-69, Jackson's 'Working Class Community' study 1961-68; Cousins and Brown's 'Tyneside Shipbuilders study' (1968-70). On the Affluent worker study see Savage 2005b

8 I benefited from a conversation with Dorothy Sheridan which broached these issues. She noted that many Mass-Observation researchers feel compelled to read every letter, and wondered how far this was a useful practice.

9 The Mass-Observers were expected to write on a sheet of pro forma in which they had to state their age, occupation, and marital status. Although not all Mass- Observers complied, it is still possible to use the information on occupation to be sure about their social composition.

10 Actually, Martin's survey was only conducted in two locations, Greenwich and Hertford, and is not necessarily representative of Britain.

11 My analysis offers a rather different account to that given by Marwick (1996: 41-2), who quotes testimony from four housewives from this Directive to emphasise the strength and clarity of the middle-class self image. However, his four cases are not representative of the broader sample.

12 i.e the upwardly socially mobile

13 Mckibbin (1998: 104) writes of middle class self perception being shaped 'largely by an ideological hostility to the organized working class, which forged a strong sense both of middle class unity and loss, and exaggerated the cultural differences between the middle class and working class way of life'.

14 Though in 1990, Mass-Observers were not expected to answer on a pro-forma and hence we have no easy way of assessing their occupational position

15 Mass-Observation Directive

16 Such an interpretation would be supported by a reading of the five Mass-Observation diaries between 1945 –1948 collected by Simon Garfield (2004) which indicate a sense of alienation of the middle class diary writers from the Labour government. It is possible that Mass-Observers in the late 1930s may have been more reflexive and critical (and see Hall 1972, Hubble 2006).

References

BAUMAN, Z., (1998), Work, consumerism and the new poor', Milton Keynes, Open University Press.

BECK, U., (1992), Risk Society, London, Sage.

BISHOP, L (2007), 'A reflexive account of re-using qualitative data: beyond primary/ secondary dualism', <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/3/2.html>

BLACK, L. (2003), The political culture of the left in affluent Britain, 1951-1964, Basingstoke, MacMillan.

BLACK, L. and Pemberton, H., (2004), An Affluent Society: Britain's post-war "Golden Age" revisited, Aldershot, Ashgate.

BOURDIEU, P. (2001), Pascalian Meditations, Cambridge, Polity.

CASTELLS, M. (1998), End of the Millennium, Oxford, Blackwells.

CLAPSON, M. (1998), Invincinble New Suburbs, Brave New Towns: Social Change and Urban Dispersal in post-war England, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

CORTI, L. (2004), 'Archiving Qualitative Data', in M. Lewis-Beck et al, the Sage Encyclopaedia of Social Science Research Methods, London, Sage, Vol 1.

FIELDING, N. (2004), 'Getting the most from archived qualitative data: epistemological, practical and professional obstacles', in Thompson and Corti, 97-104.

GARFIELD, S. (2004), Our Hidden Lives: The everyday diaries of a Forgotten Britain, 1945-1948, London, Ebury

GIDDENS, A. (1991), The consequences of modernity, Cambridge, Polity.

GLASER, B., and Strauss, A. (1968), The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson

GOLDTHORPE, J.H. (1980), Social Mobility and the Class Structure in Modern Britain, Oxford, Clarendon.

GORER, G. (1955), Exploring English Character, London.

HALL, S. (1972), 'The social eye of Picture Post', Working Papers in Cultural Studies, No 2.

HALSEY, A.H., and Webb, J. (2000), Twentieth Century British Social Trends, Basingstoke, MacMillan

HAMMERSLEY, M. (1997), 'Qualitative Data Archiving: some reflections on its prospects and problems, Sociology, 31, 1, 131-142.

HAMMERSLEY, M. (2004), 'Towards a usable past for qualitative research', in Thompson and Corti, p 19-28

HIGGS, E. (2004), The Information State in England, Basingstoke, MacMillan.

HUBBLE, N. (2006) Mass Observation and Everyday Life: Theory, Culture, History, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan

INGLEHART, R. (1990), Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Societies, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

INGLEHART, R. (1997), Modernization and Post-Modernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 countries, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

JEFFREY, T. (1999), 'Mass-Observation: a short history', University of Sussex Library, Mass-Observation Archive Occasional Paper, No 10

JOYCE, P. (2003), The rule of freedom: liberalism and the modern city, London, Verso.

KUSHNER, T. (2004), We Europeans? Mass-Observation, "race" and British identity in the Twentieth Century, Avebury, Ashgate.

MCKIBBIN, R. (1998), Classes and Cultures: England, 1918-1951, Oxford, Clarendon.

MARTIN, D. (1954), 'Some subjective elements of class', in D.V., Glass (ed), Social Mobility in Britain, London, Routledge.

MARWICK, A. (1996), British Society since 1945, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

MITCHELL, T. (2002), The rule of experts, Berkeley, University of California Press. ,

MOORE, N. (2007), '(Re)using Qualitative Data', paper prepared for CRESC Re-using qualitative data workshop, September 28th <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/3/1.html>.

POOVEY, M. (1998), A history of the modern fact: problems of knowledge in the science of wealth and society, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

ROSE, D. (ed) (2000), Researching Social and Economic Change: the uses of household panel studies, London, Routledge

ROSE, J. (2001), The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, New Haven, Yale University Press.

SANDBROOK, D. (2005), Never Had It So Good: A history of Britain from Suez to the Beatles, London, Little Brown.

SAVAGE, M. (2000), Class Analysis and Social Transformation, Milton Keynes, Open University Press.

SAVAGE, M. (2005a) Revisiting Classic Qualitative Studies', Historical Social Research/ Historische Sozialforschung, Vol 30, No 1, 118-139.

SAVAGE, M. (2005b), 'Working class identities in the 1960s: revisiting the affluent worker study', Sociology, 39, 5, 929-946.

SAVAGE, M. Bagnall, G., Longhurst, B.L., (2001), 'Ordinary, ambivalent and defensive: class identities in the North-West of England', Sociology, 35, 875-892.

SILVA, E.B. (2007), 'Re-using qualitative data: what's (yet) to be seen?', <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/3/4.html>.

STANLEY, L. (1995), Sex surveyed: from Mass Observation's 'Little Kinsey' to the national survey and the Hite Report, London; Taylor and Francis.

STRATHERN, M. (1990), After Nature, Oxford, Clarendon.

SZRETER, S. Fertility, Class and Gender in Britain, 1860-1914: Cambridge; Cambridge University Press.

THOMPSON, E.P. and Yeo., E (1972), The Unknown Mayhew, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

THOMPSON, P. and Corti L., (2004), Special issue – celebrating classic sociology: pioneers of contemporary British qualitative research', Social Research Methodology, 7, 1, pp 1-108.

WARD, S (ed), (2001), British Culture and the Decline of Empire, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

WEIGHT, R. (2002), Patriots: national identity in Britain, 1940-2000, London, Pan.

ZWEINIGER-BARGIELOWSKA I. (2001), Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls, and consumption 1939-1955.