The Time Economy of Parenting

by Anne Gray

London South Bank University

Sociological Research Online, Volume 11, Issue 3,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/3/gray.html>.

Received: 9 Jan 2006 Accepted: 9 Aug 2006 Published: 30 Sep 2006

Abstract

This paper explores how the UK Time Use Survey (UKTUS), together with the author's qualitative interviews and focus groups with London parents, can inform current policy debates about childcare and parental employment. It also refers to the international literature about long-term trends in parental childcare time. It addresses four key questions about time use and parenting, which have implications for theorisation of the `gender contract' regarding childcare and for our understanding of the gendered distribution of time between care, work and leisure in two-parent families. How is total parenting time affected by parents' work hours? How do the long work weeks of British fathers affect their capacity to share childcare with mothers? Would childcare time rise if work hours were more equally distributed between women and men? This invokes a discussion of how far childcare is really transferable between parents (or can be delegated to external carers); to what extent is it `work' or a relational activity?

Keywords: Fatherhood Gender-Contract Parenting Time-Use Work-Life-Balance

1. Introduction

1.1 The feminist concern that fathers could and should do more childcare invokes the question whether they have the time-resources to do so. Historical trends in time use, discussed in section 4, show fathers taking a more active childcare role in recent decades in the UK and many other industrialised countries (Gauthier, Smeeding and Furstenberg 2004), although the pace of change towards gender equity is slower than mothers and feminists might wish (Gershuny, Godwin and Jones 1994; Pilcher 2000). Recent attention to work stress also raises the issue of whether parenting quality is compatible with a continued increase in the family's labour supply to the market-place. Changing expectations of fathers' roles appear to conflict with the very long working hours prevalent amongst them in the UK (Dex 2003, O'Brien and Shemilt 2003, Fagan 2003). This is allied to growing concern with the specific contribution fathers can make to their children's development (O'Brien, 2004). To pursue this role, many fathers are keen to modify traditional male employment patterns (O'Brien 2004; Smeaton and Marsh 2006). Both qualitative and quantitative data presented here suggest that long work weeks for fathers are currently associated with significant constraints on their childcare role.1.2 This paper uses the UK Time Use Survey to investigate the cross-sectional relationships between childcare time and parental employment. It examines the effects of the `long hours culture' and enquires how shorter work hours for fathers would affect the time they spend on childcare. The author's qualitative research is used to investigate the way parents, particularly fathers, perceive and respond to time conflicts between childcare and paid work. It also asked parents how and why childcare practices have changed since their own childhood. The qualitative work thus attempts to understand how the quantitative data, both cross-sectional and trends, emerge from changing practices of family life, differentiated by class and education.

2. Data sources and methods

2.1 The UK Time Use Survey (UKTUS), conducted in 2000, can be compared with some earlier UK surveys of similar nature, as described in section 4, and with similar surveys in many other countries at various dates reaching back to the 1970s. In over 6000 households, each person over 8 years old was asked to complete two diaries, one for a weekday and one for a weekend day, recording in their own words, what they did in each ten-minute period over 24 hours. Respondents could record both a primary (main) activity and a secondary activity for each period. Their replies were coded as one of 150 activity types, some further sub-divided. The household sample contains 623 couples with children under 12 where the parents can be matched together and who completed at least one diary each.[1] In these, 592 fathers and 573 mothers completed both diaries; missing data mean further falls in sample size on some variables. Additional information comes from the individual and household questionnaires.2.2 Over 98% of couples with children under 12 record some primary childcare – including child-escorting - by at least one parent over the two diary days; all do some secondary childcare. Only 3.7% of mothers do no primary childcare on either day, and only 2.7% do no primary or secondary childcare. Fathers' childcare is much more variable than mothers'; 17.7% of fathers do no primary childcare on either day and 12% do no secondary childcare either.

2.3 How should we measure parental availability – childcare or co-presence? Bruegel (2004) observes that being `with' the child may not mean being actively engaged with the child – who may even be asleep. Moreover she shows that `only half the time spent by parents at a park with a child ….was coded as childcare' – reflecting a blurred distinction between `family outings' and `accompanying children' in the way parents complete their diaries. Activity described as childcare (either primary or secondary) is less than 30% of the total time fathers are with children and 42% for mothers. However, most time use researchers analyse time described as childcare, especially where it is the primary activity (Gauthier et al. 2004; Sayer, Bianchi and Robinson 2004). Multi-tasking respondents probably record whichever two activities they think most important, or whichever involve most attention (Bittman, 1999).

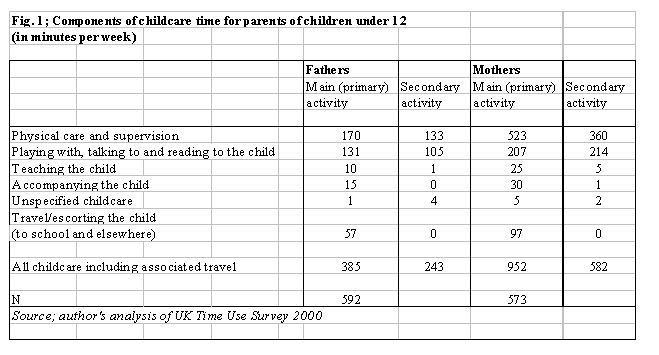

2.4 Fig. 1 shows the activities recorded in the UKTUS under the `childcare' heading. It gives `minutes per week' estimates; adding twice the weekend diary figure to five times the weekday diary figure, an established procedure in time use research. Teaching the child, accompanying and travel associated with childcare (mainly taking children to school) are nearly always recorded as the parent's main activity, whilst `playing with, reading to and talking to the child' is almost as often a secondary activity as a primary one, as is `physical care and supervision'. Further discussion of the definition and categories of childcare activities is deferred until Section 6.

|

2.5 Alongside the UKTUS analysis, the author used a qualitative sample of London parents was used to investigate their perceptions of time pressures and time allocation processes particularly around work and parenting, how they define childcare and what influences the subjective boundaries between childcare, family leisure, and other activities in children's presence. The qualitative work began in December 2004 with a pilot sample of 12 couples with 10-11 year old children, recruited through contacts with primary schools and interviewed in their homes. Recruitment through this method proved difficult, especially with fathers, and there was no way of choosing respondents according to the father's work situation. A feasible alternative was to recruit focus groups of fathers of under 12s through a market research agency. Four groups were selected in January – February 2005, comprising altogether 32 fathers, with each group's quota criteria representing different year-round work situations:-

- Manual or routine workers with typical work hours over 42 per week;

- Manual or routine workers, with typical work start time before 7.30 a.m;

- Professionals or office workers with a regular work schedule of approximately 9 a.m to 5 p.m;

- Professionals or office workers with considerable regular overtime, or weekend or shift work.

3. Gender equity, the dual earner couple and the `new fatherhood'

3.1 Much of the literature on time use and childcare has focussed on the division of labour between parents and the redistribution of childcare from women to men as women's labour market participation has risen (Gershuny, Godwin and Jones, 1994, Gershuny, 2000; Gershuny and Sullivan, 2001; Layte, 1999; Pilcher, 2000). The pace of this redistribution appears to have slowed around the millennium, due to the pressure of increased work intensity for men (Crompton, Brockmann and Lyonette 2005).3.2 In the debate about work stress in dual earner households – professional couples especially - a `time famine' is identified for partnered women in full-time employment (Brannen 2004, Warren 2003). Bittman (2002; 2004b) finds `time poverty' [2] for mothers, but not fathers, in Australian couples with two full-time earners, and indeed for all mothers of under two's. Mothers, even when employed full time, delegate much bathing and feeding of children to external carers, whilst sacrificing leisure to maintain the time they spend playing and talking with children and teaching them; but fathers' time in these activities is much more sensitive than mothers' to working long hours (Bittman and Folbre 2004). In Britain there has been recent concern that a time famine for fathers may affect childcare (Kilkey 2005), in her view insufficiently reflected in recent developments in UK parental employment policy which has, in effect, been more concerned with maximising the labour supply of mothers. The `long hours culture' generates time conflicts for fathers between work and parenting (O'Brien 2004). Stress about their fatherhood role is especially experienced by fathers working over 50 hours weekly (Ferri and Smith 1996). Warren (2003) notes that for working class couples the gender pay gap, low purchasing power over external childcare, and men's lack of sovereignty over work time all impede sharing of paid work and care between parents. In `male breadwinner' working-class families, the father may be trapped into long hours to earn enough, and the mother into economic inactivity because his work hours prevent him from helping much with childcare.

3.3 The shortage of fatherhood time for long hours workers is nothing new; Warren (2003) highlights studies of lorry drivers, fishermen, etc in the 1960s who lamented seeing too little of their children. What has changed is the demise of the `male breadwinner' model of family life, together with rising expectations of fatherhood. There is a `shift in cultural norms and values governing contemporary fatherhood' (O'Brien 2004, p. 3), generating potential conflicts of (especially long-hours or `presentee-ist') employment with the accessibility, nurturing role and sharing of childcare now expected of fathers.

3.4 Without policies to reduce fathers' hours, increasing employment of mothers means a rising family labour supply, at the expense of family time and leisure. The `equal rights' feminists of the 1970s emphasised a goal of redistributing unpaid work and childcare, but with little discussion of whether this requires shorter hours of paid work for men. They argued that women's equality depends on being enabled to work on the same terms as men, i.e. to work as many hours per week as men normally do and at equal pay (Dalla Costa 1973; Oakley 1974). Fraser (1997) describes this as the `Universal Breadwinner' model, which she argues may lead to gender inequality in leisure – an expectation confirmed by time use research in relation to couples with two full-time earners (Bittman 2002, 2004b) and other sources (Brannen 2004; Warren 2003). Mothers are wary of the leisure deficit associated with full-time employment alongside the (still mainly female) role of childcare; Perrons (2000) cites evidence from the Labour Force Survey that over 90% of mothers working part-time in Britain do not want a full time job.

3.5 The Unversal Breadwinner model is one of three alternative models of gender equity discussed by Fraser (1997). Her second, `Caregiver Parity', attempts to remove financial and status disadvantages from care-giving, recognising and respecting care-giver status rather than attempting a gender redistribution of care and work. Perrons (2000) describes its objective as `to make the difference between men and women's current lifestyles costless'. Its drawback is the expected persistence of the gender gap in pay and occupational status. Fraser's third model is the `Universal Caregiver', in which `all jobs would be designed for workers who are caregivers too; all would have a shorter workweek than full-time jobs have now; and all would have support of employment-enabling services' (italics AG). She argues for the superiority of this third model in terms of seven dimensions of gender equality. The `Universal Caregiver' model is consistent with the notion of the `new fatherhood' in which fathers have a very specific role in their children's development.(O'Brien 2004).

3.6 Central to the Universal Breadwinner model is a reliance on non-parental childcare to enable mothers to enter employment. This shift from parental to external care is unproblematic if childcare is entirely a `task' like housework, which can be adequately outsourced. In so far as it cannot, we must ask whether the relational aspects of childcare present a time requirement for the parent couple which is squeezed in dual earner households. Do fathers' work hours need to shrink as mothers' work hours rise, for parent couples to spend enough time on childcare? Independently of this, do the parenting practices expected of the `new fatherhood' demand that fathers should work shorter hours anyway, regardless of the mother's availability?

3.7 In a powerful essay about the nature of `domestic labour' Himmelweit (1995) argues that caring activities are `work' if they can be delegated to others, but that certain aspects of childcare cannot be delegated, being part of the relationship between parent and child. In her view the characterisation of childcare as `domestic labour', as `work' which can be `commodified' obscures the relational and self-fulfilling significance of caring activities. Extending Himmelweit's analysis to the issue of the distribution of childcare between mothers and fathers, one may argue that some aspects of childcare are non-transferable between couple parents. That is, mother's time and father's time are not entirely interchangeable; children need some time to interact with each parent, and each parent with them. Sufficient time for parenting would then imply a need for fathers' paid work hours to be limited as well as the aggregate hours worked by the parent couple. The concept of childcare as transferable work sits uneasily with the notion of the `new fatherhood'.

3.8 Time use research, in discussing gender equity, has often defined childcare as a form of `domestic labour' (Gershuny, Godwin and Jones, 1994; Gershuny 2000; Gershuny and Sullivan 2001; Layte 1999), a work-like `task' which could be transferred to fathers or to non-parents without changing its nature. This notion also survives in some recent literature on gender contracts (e.g. Pilcher 2000; Warren 2003). Whilst Bittman (2004a) characterises childcare as non-market `work' as a convenient shorthand in analysing mothers' leisure deficit, to take this too far may risk neglecting the nature of childcare as a relational activity.

3.9 Conversely, some time use researchers have taken a `social capital' approach, which defines childcare as centrally a relational and human development activity. The social capital perspective, in which parents and schools are constructed as investing time in children, has become the focus of a large literature on the interaction between parenting, child development and education (Coleman 1988; Morrow 1999; Putnam 2000; Bourdieu 1986). Several time use researchers in the USA (Bianchi 2000, Sandberg and Hofferth 2001, Sayer, Bianchi and Robinson 2004, Bryant and Zick 1996) have addressed the concern of Coleman (1988) that children's `social capital' inheres partly in parental availability, and that the quality of parenting might be falling because of increased maternal employment. They conclude that Coleman's fears were unfounded for the USA, where childcare time by both parents rose towards the end of the twentieth century despite more mothers taking jobs.

3.10 One may detect some similarities between Esping-Andersen's (2002) advocacy of a `child-centred social investment strategy' and Coleman's (1988) construction of parental attention as `social capital'. Both suggest that labour time may be `invested' in child development, but Coleman emphasises parental labour time whilst Esping-Andersen advocates a `social investment' state in which both parents and childcare services contribute to children's upbringing, and the labour time of either may be subsidised to secure sufficient time resources for this activity. This again raises the question of how far parental and non-parental childcare is interchangeable – in other words, to what extent is it, in Himmelweit's terms, a relational activity which cannot be delegated? We return to this question in section 6.

4. Historical trends in parental childcare time and employment

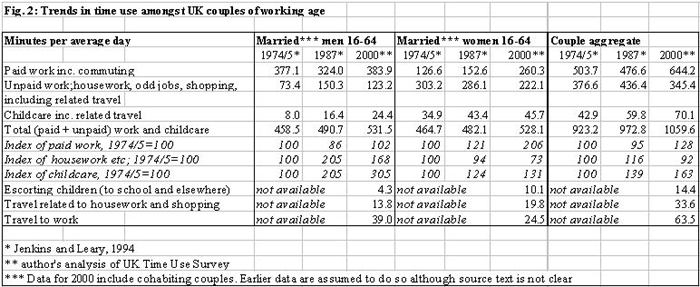

4.1 Recent labour market trends in Britain have raised the amount of paid work per couple, but childcare time has also risen. Mothers' employment rate rose from 55% in 1984 to 67% in 2004.[3] In 1984, only 22% of employed mothers with partners worked full-time, whilst by 2004 28% did. Fig. 2 shows how UK couples' time use has changed from 1974/5 to 2000; unfortunately parents and others cannot be separated in this table, which is partly derived from secondary data from Jenkins and O'Leary (1997). Married women's average work hours, including commuting, have more than doubled since 1974/5. Men's hours fell from 1974/5 to 1987 then rose again to their 1970s level. Thus total paid work per couple by 2000 was 28% more than in 1974/5. Taking all working-age couples together shows falling leisure, contrary to the `rise in leisure' argued by Gershuny (2000). He separates couples by the woman's employment status, thus obscuring the leisure-reducing effect of the shift from the `breadwinner' model towards two-earner households.

|

4.2 Despite the increased paid work time per couple, childcare time has also risen – by 205% for men (including non-fathers) and 31% for women (including non-mothers) over 25 years, helped a little by the decline in housework. Childcare is defined here as time which the respondent says they spent actively engaging with children, for example washing, feeding, playing with, or talking to them. It does not include all the time when the respondent parent is `responsible', e.g. for a sleeping child, whilst the other is out. In several countries, time use survey data from recent decades show both parents spending more time on childcare despite the higher employment rate of mothers. Fisher, McCulloch and Gershuny (1999) suggest British fathers' childcare time almost quadrupled between 1960 and 2000. A rise in father's childcare was also found by Sayer, Bianchi and Robinson (2004) for the USA between 1965 and 1998; by Bittman (2004a) on Australia between 1974 and 1997; and in a harmonised data set on parents of under 5s combining time use surveys over the last 40 years from the USA, UK, Canada, Australia and 12 other countries (Gauthier, Smeeding and Furstenberg, 2004). In almost all these studies, fathers increased their childcare time more than mothers, thus raising the father's share of aggregate parental childcare. In the USA, Sandberg and Hofferth (2001) and Bianchi (2000) show that time each parent spends with children (rather than `childcare') increased in two-parent families between 1981 and 1997; but the time children spend without either parent barely fell, since father's time with them came to overlap more with mother's.

4.3 Do these trends represent an actual increase in childcare time, or greater reporting of it in surveys? Historic trend data reflect changes not only in what people do, but how they describe it. Parents, especially mothers, frequently multi-task (Bittman and Wajcman 2000). If parents now attach more importance to childcare, more multi-tasking periods may be classified as `childcare' in the most recent surveys; or elements of childcare which were once recorded as secondary activity may now be described as primary activity (Van de Lippe and Ruijter, 2004).

4.4 The apparent rise in fathers' childcare role is contested by Ferri and Smith (2003) and Calderwood et al (2005), who find from longitudinal cohort studies that fathers in their early 30s now play a smaller role in childcare than those who were the same age then did in 1991. This finding is based on questioning both parents about who had the main responsibility for looking after the children, who cares for them when the other partner is working or when the child is sick. It runs contrary to the impression of the trend since the 1980s based on actual time use surveys, described above. However, the contradiction reminds us that responsibility for children is multi-dimensional; it is not only a question of time spent, but also of degree of responsibility and decision-making. Whilst time use surveys collect information only on the amount of time spent looking after children, the National Child Development Study and similar questions in the British Household Panel Survey probably reflect parents' views of all three dimensions.

4.5 Rising parental childcare time may be partly due to rising parental education levels. Several studies suggest that better educated parents spend more time in activities with their children (Bianchi 2000 on the USA, Bittman, Craig and Folbre 2004 on Australia; Kitterød 2002 on Norway; Gauthier et al. 2004 on several countries). Increased traffic and perceived `stranger danger' may also have increased the time parents need to ensure children's safety en route to school or other activities (Bianchi 2000). Travel associated with childcare (e.g. taking children to school) adds around a quarter to parents' `pure' childcare time as a main activity in the UKTUS. The National Travel Survey showed 39% of primary school children being taken to school by car in 1999-2001, compared to only 27% in 1989-1991.[4] Particularly when the parent is driving, growth in `escorting' time may not contribute much to parent-child interactions.

5. Does work currently constrain father's childcare time?

5.1 The author's qualitative research with fathers in London confirmed Schoon and Hope's (2004) finding that many fathers would like to spend more time with their children, being prevented by long work hours. When asked how they would spend an extra half day a week off work if they could have one, time with children and more sleep were the most common answers, although some participants also mentioned home improvements. These respondents attached rather more importance to having more time for childcare than fathers in the UKTUS, of whom 7% gave this response against 36% who wanted more exercise.5.2 The strongest impressions of a time squeeze on fatherhood came from focus group 1, manual workers with very long working weeks. Some worked overtime from financial necessity, but others had reduced work hours, and income, to have more time for childcare. The three other focus groups sensed less time-pressure; one contained manual-worker fathers with shorter hours, and two had fathers with office jobs. The office workers rarely worked weekends, leaving clear periods of `quality time' for their children even for those whose managerial responsibilities pushed their work hours above 45 weekly. Turning to the UKTUS data, a clear negative relationship emerges between fathers' work time and their childcare time, which is explored further in section 7. Amongst fathers whose work plus commuting totals over 50 hours per week (over 4 out of 10 in the sample) 20.4% do no childcare at all, compared to only 5.6% of those with shorter weeks (p<0.001 on chi-squared test).

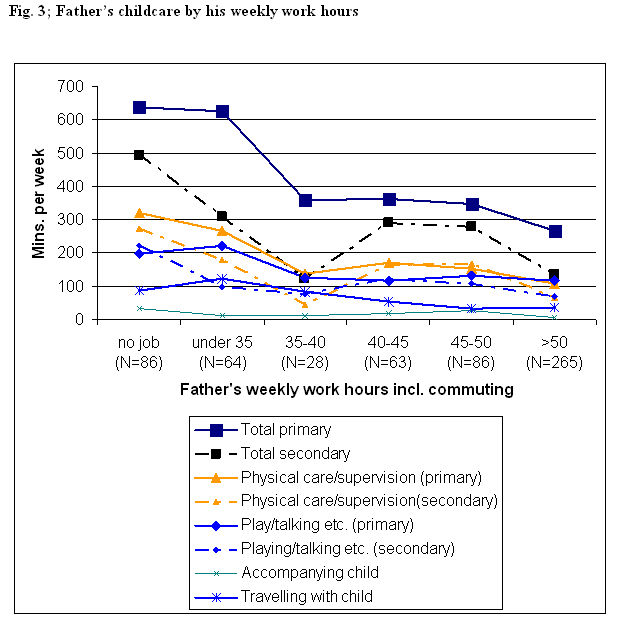

5.3 Fig. 3 shows how the different components of father's childcare vary with his work hours. Total primary childcare almost doubles if father works under 35 hours – though only 25% do. In all components, significantly less time is spent by the 45% of fathers who work over 50 hours weekly.[5] The diary data support the hypothesis derived from the focus group material; that very long work hours squeeze fathers' interactions with children.

|

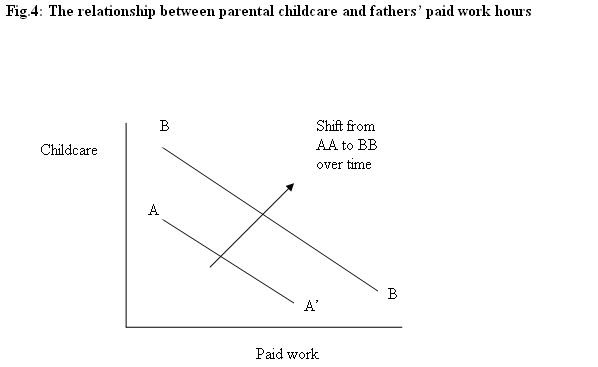

5.4 All the evidence considered here points to a negative effect in Britain of long paternal workweeks on fathers' childcare time. Why, then, does the trend data presented in Fig. 2 show that fathers substantially increased their childcare time over recent decades, despite little reduction in their working hours? Fig. 4 offers a possible interpretation. There is a negative `trade-off' between their work time and their childcare time in cross-section, and this `trade-off' gradually shifts outwards as the years go by, so that both parents are doing more childcare at a given level of work week than before. If a relatively long work week merely constrained individual fathers from freeing mothers to take jobs, the resulting conflicts around mothers' employment could be resolved by improved childcare services. However if fathers' long hours reduce the quality of father-child relationships, this would provide additional reasons, beyond the goal of gender equity, for promoting the `Universal Caregiver' model over the `Universal Breadwinner' model. In the next section, we turn to the qualitative data to examine this issue.

|

6. Distinguishing the `domestic work' and `relational' elements of childcare

6.1 We now explore Himmelweit's dichotomy of childcare activities in order to better analyse the relationships between work time and childcare time. One study which has implicitly touched on the Himmelweit dichotomy is that of Bittman and Folbre (2004), who distinguish four types of childcare activity:-- developmental ; playing with, talking to, reading to and teaching children

- high contact – physical interactions around meals, bathing, cuddling and comforting, putting to bed

- low intensity or `passive' childcare, mainly conducted as secondary activity

- travel

6.2 This typology appears problematic in so far as category (a) overlaps with (b) and (c). As noted in section 2, much of fathers' time playing with children or talking to them is a `secondary' activity, which might make it `low intensity' because father's main attention is elsewhere. By contrast watching TV with children may be `low intensity' but may be a relationally significant activity for some parents – and some children. Physical interactions, Bittman's category (b), have more `relational' meaning and developmental significance for very young children. Some fathers of toddlers, in the author's focus groups, like `the small things'; feeding children and putting them to bed.

6.3 The author's qualitative work revealed that parents perceived parental childcare time mainly in terms of four main functional elements which, apart from travel (the school run, etc.) are distinguished primarily in terms of what the other parent was doing. These are illustrated in Fig. 5 and the quotations linked to it; hyperlinks in pink lead to mothers' statements, those in blue to fathers'. Two childcare elements seemed to be largely regarded as `work' in the dichotomy of domestic `work' or relational activity discussed in Section 3. Firstly, fathers provided `cover' whilst mothers were at work. `Cover' was something which mothers had to negotiate rather than expect – would father arrange his own work schedule to be available, cook meals for the children, share the `school run', be there in emergencies? For some fathers this `babysitting' was a resented chore (see quotes 25 , 26 , 28) . They associated `babysitting' with housework, with which it was multi-tasked (quotes 25, 9). Other fathers, however, valued time spent `covering' for the employed mother as a period for deepening their paternal relationship or doing something special.

| Table 5: A typology of childcare elements | |||||||||

| 1.`Cover' or `babysitting' whilst other parent at work | 2. Escorting children, e.g. to school | 3.Both parents doing childcare together | 4. Father's time/mother's time (alone with children) | ||||||

| `Chore' or `work-like' – someone else could do it under suitable conditions | See quotes 14, 24, 25, 28 | See quotes 1, 2, 4, 5, 24 | See quote 20 | See quote 3 (mother describes father as helping her with `work' Also see quotes 12, 19, 22 part a | |||||

| Relational activity – non-transferable to others | See quotes 9 and 21 | See quote 7 | See quotes 6, 8, 11, 13 | See quotes 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 22 part 23, 26, 27, 29, 30 | |||||

| How this element can be identified in UKTUS | One parent doing primary or secondary childcare whilst other is at work | Specific diary activity codes of taking children to school and taking them elsewhere | Both parents engaged in childcare simultaneously | One parent doing childcare; the other doing something which is neither work nor childcare | |||||

| Average time (minutes per weekday) spent on this element in UKTUS by parents of under 12s | |||||||||

| Mother | 80 | 31 | 15 | 68 (of which 46 primary activity and 22 secondary activity) | |||||

| Father | 16 | 10 | 15 | 25 (of which 16 primary, 9 secondary) | |||||

| % of parents spending no time on this element | |||||||||

| Mother | 32.7[*] | 45.7 | 63.0 | 21.7 | |||||

| Father | 73.1[*] | 77.2 | 63.0 | 51.6 | |||||

Note to reader: links in pink indicate mothers' statements, in blue fathers' statements. For information about who was in each fathers' focus group, refer to section 2.

*Of those with employed partner.

6.4 A second major element of childcare is taking children places – not only to school but to music lessons, sports sessions, supplementary tuition or to visit their friends. Both parents regarded this too mainly as a chore; it involves much driving and complex planning, especially when each child attends different schools or activities (see quote 24, quote 4). However a leisurely walk to school (rather than driving) was seen as valuable time to chat (quote 7). Parents felt that dangers to children in public places had greatly increased the need for escorting them to school and elsewhere since they themselves were children (see quotes 2 and 20).

6.5 A third element, `family time' when both parents were with the children, was not a chore but valued as an important aspect of family relationships. It included outings to family sports activities, restaurants, museums, shopping as leisure, parks and picnics. These activities may be recorded in time use diaries as leisure, rather than childcare.

6.6 A fourth element is time spent by one parent with a child when the other parent is not at work. Fathers are sometimes alone with children because mother negotiates to go out for community activities or leisure (quotes 31, 19). But they also value the relational quality of spending time alone with their children, which they are more likely than mothers to do by choice rather than obligation. Some mothers, on the other hand, do link childcare and housework in the same breath, seeing both as obligations (see quote 3), or longing for time on their own (quotes 12 and 14).

6.7 Fathers emphasised the need to spend `quality time' with their children, time for `getting to know your child'. They wanted more time to take the children out, to help them with homework, to talk to them. Any normative pressure to spend time alone with children in this way came from fathers' own recognition of changed social expectations about fathering (quotes 16, 19 and 20) which seemed to be independent of the need of employed mothers for `cover'. Fathers viewed time spent with children in outings, sport, play and conversation as an expression of fatherhood, rather than a form of domestic `work'. They emphasised the need for relationship-building time which could not be delegated to anyone else, as the following comment illustrates:-

`I want to try, no matter how much I'm working, even if it means I take him in the pub with me, and we sit down and he has a soft drink and I have a beer and we spend an hour in there just chatting, saying how was school this week, what you done this week, … no matter what I've been doing all week I should try and find time to talk to him….I think your kids they should be more like your friends as well as your kids, you know, kids years ago will have been seen and not heard sort of thing but now kids are a lot more outgoing, a bit more educated so you can actually hold a proper conversation with them about their school work, relate to them a bit more' (manual worker, father of 10 year old; italics AG)

6.8 The parents' statements suggest that fathers regard family time and time when father is alone with a child as activities which shape and fulfil their role as fathers; and which they try hard to guard against the intrusions of work pressures. Using Himmelweit's (1995) test of `what is work', these are activities which could not readily be transferred to the mother or a childminder. However, the `chore' elements of parenting, like driving children to school or providing `cover' for employed mothers are perceived more like `work' which can be delegated to other child-carers where possible (quote 24).

6.9 Childcare done whilst the other parent is working tends to be defined as `work'; periods when both are childcaring as `family time', i.e. relational activity. Periods when one parent is childcaring and the other doing neither work nor childcare are more ambiguous, but are more likely to be `relational' than work in the sense that there is a negotiated choice from day to day. Each of these four elements of childcare identified in the qualitative work is roughly distinguished by the combination of parental activities recorded in the UKTUS for each ten-minute period. Fig. 5 (rows 4 and 5) show estimates of the average time mothers and fathers spend on each one. The UKTUS data are an imperfect instrument for quantifying the separate elements, because some time when father is `covering' for a mother at work or vice versa (element 1) may also contain periods when the parent would have anyway wanted intensive parent/child interaction (element 4). But these categories, derived from the qualitative work bring us nearer to a typology of childcare based on parents' desires and decision processes than the UKTUS data could alone. As we shall see in the next section, childcare as `chore' and childcare as relational activity behave differently in regression models of the relationship between childcare and work hours.

7. Predicting the effect of a reduction in father's work hours (with a corresponding rise in mother's)

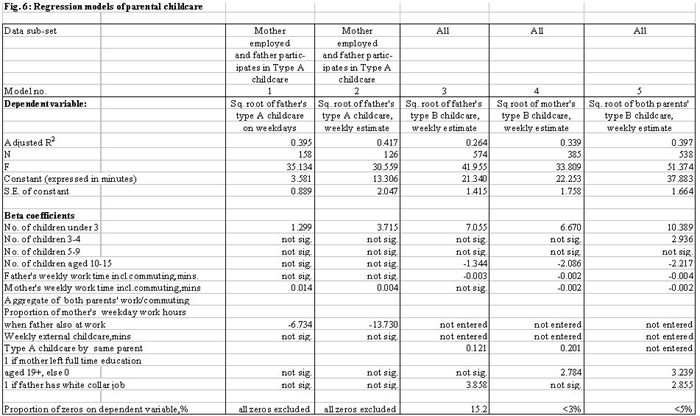

7.1 We now use regression models to examine the sensitivity of each childcare type - `relational' and `chore' to father's work hours. We divide childcare into elements 1 plus 2 ( childcare as `domestic work' or `babysitting', denoted here as type `A' childcare) and elements 3 and 4 added together (`relational childcare' or `bonding' activity, denoted as type B), whilst recognising the blurred boundary between them as well as the somewhat rough and ready correspondence between each type and the UKTUS indicators identified in Fig. 5.7.2 In modelling Type A childcare (Fig. 6, models 1 and 2 [6]), we introduce a measure of overlap in the two parents' work schedules; the proportion of the mother's weekday work hours when the father is also working. Father's type A childcare on weekdays rises with the mother's work hours, but falls to the extent that he is at work when she is. This `overlap' measure is a better predictor of father's Type A childcare than his actual work week, although the two are highly correlated. For mothers employed part-time, paternal `cover' is more feasible because the parents' work hours are less likely to overlap. Where mother is employed part-time, only 60.9% use non-parental childcare, compared to 73% where she works full-time.[7] Use of non-parental childcare in itself is not, however, a significant predictor of either the father's childcare or aggregate parental childcare.

|

7.3 Amongst fathers whose partners do some paid work on the diaried weekday, 62% do no type A; these fathers have a much longer average working day; 8.5 hours compared to six hours for those who do some (F=47.908; p<0.001). Only 52% of fathers do any type B childcare on weekdays, and 39% none of either kind. However, when weekend diaries as well as weekdays are taken into account, only 16% of fathers record no type B childcare on either day.

7.4 Because fathers and children obviously spend more time together at weekends, we now move to measuring childcare time over the whole week – estimated as five times the weekday amount plus twice the weekend day amount. The whole-week model for Type A childcare for those fathers who do any (model 2) is similar to the weekday one (model 1); again, the `overlap' measure predicts father's Type A childcare better than his own working hours. However, father's work hours do affect his weekly type B childcare (Model 3 in Fig. 6). Those fathers who do no type B have a much longer work week (53.9 hours) than those who so some (41.7 hours[8]). Their type B childcare time is significantly lower if their work week, including commuting, exceeds 50 hours; only 121 minutes compared to 154 minutes for those with shorter weeks.[9] The mother's weekly work hours do not affect father's type B childcare. The regressions also show that white collar fathers do more childcare of both types, controlling for work hours and children's ages. Model 4 in Fig. 6 shows that Type B childcare by the mother is affected by father's work hours as well as her own work hours and her educational level.

7.5 Concerning the effects of social class on fathers' childcare, the UKTUS does not support findings from some other sources. Whilst Warren (2003), Ferri and Smith (2003) and Fisher et al (1999) find that middle-class fathers are less involved in childcare than manual workers, the UKTUS shows the contrary. Manual/routine and self-employed fathers (most of whom have manual jobs) spend significantly[10] less time (548 mins. per week) than white-collar fathers (705 mins.). Amongst manual/routine job and self-employed fathers, 16.7% do no childcare, compared to 7.2% of white-collar fathers who do none (p<0.001). Methodological differences may explain this contradiction with the earlier work, of which only Fisher et al.'s evidence is based on diaries, and then for studies prior to the UKTUS in 2000.[11] Highly educated fathers are also more likely to do some childcare (95.5% do out of those who completed full-time education after their nineteenth birthday, compared to 86.6% of other fathers; p=0.008 on chi squared test).

7.6 What then would be the effect of a substantial reduction in men's working hours, the key policy change needed to move towards Fraser's `Universal Caregiver' model? One would expect a major gender re-distribution of paid work to be accompanied by a long-term redefinition of family roles, which might either drive this change or be led by policies to re-distribute paid work. Regression models derived from cross-sectional data cannot depict the long-term shift of the work/childcare trade-off, described earlier in Fig. 4, which would probably go with such a role change. But they can depict the short-run movement along the current trade-offs between work and childcare. This is the movement portrayed in the regression models in Fig. 6 which we now use to predict the effect of a reduction in fathers' work hours.

7.7 A fall in father's hours makes him more available to provide `cover' for his employed partner. Models 1 and 2 show that he would provide more `cover' if shorter hours increased his availability during mother's actual hours of work. Some mothers would respond to this by spending more hours in employment. This is particularly likely if father's shorter work hours meant lower earnings. If fathers reduced their hours by say nine weekly (from their average of 44.2 hours to 35.2 hours), Model 3 predicts that their type B childcare would rise. If mothers increased their work hours by nine hours, to make up the family income, Model 4 shows that mothers' Type B childcare time would fall in response to their own work hours rising, but that the rise in response to father's shorter work week would more than offset this. Putting all these effects together, Model 5 predicts that a transfer of nine hours paid work weekly from father to mother, for example in a manual-father family with one baby and one four year old, would result in aggregate `relational' (type B) childcare by father plus mother rising by 3 hours 5 minutes a week.

8. Conclusion

8.1 The policy context of the recent concerns about time pressures on parents is troubling. There is an all too easy elision between the feminist policy objective of improving female employment opportunities, and that of increasing labour supply for the economy – particularly without a policy goal of reducing men's work time. Current EU policy guidelines call for longer working hours to provide additional labour in Europe's `ageing' economies (EC, 2005, p. 4), and set targets for increasing the employment rate of women. The EU Working Time Directive to limit workweeks to 48 hours is being modified to give employers more flexibility. Thus we find in contemporary Europe an employment policy oriented towards maximising labour supply of both men and women, alongside a `gender discourse' which calls for the reallocation of domestic labour and childcare towards men. Inherent in this conjuncture is a risk that fathers may be ascribed an ideal role which is unsustainable without reducing their work hours. This is perhaps particularly true in the UK context, where 22.4% of men[12] and 31% of fathers worked over 48 hours per week in 2002[13], using the voluntary `opt-out' from the limit under the Working Time Directive. British fathers work longer hours than in most other states of the EU 15 (Kodz 2003).8.2 Long workweeks do reduce fathers' childcare time, making fathers less available to support employed mothers but perhaps more importantly cutting into periods when the whole family can be together and into fathers' `quality time' with their children. Amongst fathers working over 50 hours weekly, the proportion doing no childcare is particularly high. The way in which many fathers perceive their role is that a considerable proportion of the time they spend in childcare, probably over half on average, is a relational activity, which is distinct from the mother's role and which is not transferable to external carers either. Long fathers' work hours are shown here to reduce not only their own `relational activity' childcare but the mother's too. Thus a major redistribution of paid work from fathers to mothers as envisaged in the `Universal Caregiver' model would increase `relational' childcare by both parents.

8.3 Fathers provide childcare `cover' for the employed mother only where they are not required to be at work simultaneously. Even where this is possible, non-overlapping work schedules of mother and father imply a shortage of shared leisure time, creating a risk of relationship strain. Thus extra help from fathers is an incomplete substitute for adequate external childcare services. Some interesting comparisons are possible with Denmark, where a high maternal employment rate[14] has historically been bolstered by state childcare provision, with publicly funded childcare places for almost half of under 4s compared to Britain's 2% in 1997 (OECD 2001, p.144; Rubery, Smith and Fagan 1999)[15]. Although Danish men, like British men, do about one third of total parental childcare, Danish men's total childcare time is affected neither by their spouse's paid work time nor by their own (Deding and Lausten 2004). This might be due to the greater availability of external childcare for Danish parents, although also perhaps to lower variability amongst women's work hours – two full-time workers per couple being the norm but with less weekend working than in the UK.[16]

8.4 The gender pay gap is also an issue – for many families, a redistribution of paid work from fathers to mothers would clearly mean a lower income. Being the partner with the higher hourly earnings puts pressure on the father to work overtime. This may be one reason why only 5% of fathers in the EOC's survey (O'Brien 2004) said that shorter hours would make fatherhood easier.

8.5 As noted earlier, the historical increase in parental childcare time since the 1970s, particularly by fathers, has occurred independently of fathers' work hours and indeed despite a rise in fathers' work time between 1987 and 2000. The latest UK developments in paternal leave policy (described in Smeaton and Marsh 2006) can help to consolidate and advance the changes in attitudes which have driven this trend. However, one wonders whether the one in five fathers who record no childcare at all in the UK Time Use Survey would take up unpaid parental leave.

8.6 The findings here suggest that the most important change needed to encourage greater participation by fathers in childcare is a shorter working week, particularly for those whose work plus commuting hours exceed 50. Alleviating day-to-day time pressure is needed; parental leave, of itself, is not enough. Secondly, the findings here strengthen the case for flexitime for fathers as well as mothers; time sovereignty over the work pattern is crucial for parents to choose the balance between covering for each other and use of external childcarers which they feel is appropriate, whilst maintaining adequate `couple time' and time for the whole family to be together.

Acknowledgements

The author's work for this paper was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council at the Families and Social Capital ESRC Research Centre, London South Bank University.

Notes to Fig. 5

Quote 1 For security's sake, wherever your child is going you have to follow them so like if V[aged 10] is going to a party Saturday then it means you have to go and come and then go and pick her up, everywhere that they go you have to be there. (Mother on a council estate in south London; Ghanaian origin)

Quote 2 Taking the children to and from school is a rigid 9am and 3pm routine till the 11 year old finishes primary. It's very limiting for job choice. Since there was a kidnap attempt at the school gate, parents have been instructed to fetch even the oldest pupils. (Scottish mother on a council estate in east London)

Quote 3 I've never put the rubbish out since I married him. He'll help, he'll hoover, he'll tidy up, he'll wash the baby. He'll look after her, change her nappies, he doesn't mind doing things like that. (Mother in East London; she and her husband both Turkish)

Quote 4 I look at some of my friends and they've got younger children, so have childcare issues still. It's a stumbling block; they work and they've never got any time and they're always rushing here, there and everywhere. Because their children are still doing the different clubs. So I've kind of been through there, and am out the other side now. (White English mother in affluent south London suburb; youngest child now 11)

Quote 5 I had a day in hospital, so he took that afternoon and then the following day off work, so he could take them [to school] and he's been changing his hours so, he'll do an early rather than a late, because he can pick the children up, and then all I have to do is, get the children to school. (White English mother in affluent south London suburb; children 5 and 10)

Quote 6 We want to do as much as possible with the children; when we're not working we want to be doing stuff with the children (same informant as quote 5)

Quote 7 That's a thing that used to be lovely when I wasn't working. We would walk to the school…and chat all the way there and back. My husband asked my son one day `What do you like about Mum being at home ?' And he said, `I love our chats'. Well, we still have them now, only we have them at home. (White English mother, son now 10; she had a job when he was under 5, then stopped for a while, then started again)

Quote 8 If there's anywhere they want to go, then they usually say; can we go so-and-so at the weekend ? We might say, do you want to go bowling ? …We wouldn't take them if they didn't want to go. ..We'll say; what do you want to do ? And they might say, can we go swimming. (White English mother; children 10 and 14)

Quote 9 (Here the mother, perhaps jokingly, thinks father's evening childcare role makes him the more popular parent with her daughters) Before I go to work I'll get up with the kids, see to them; when they go I'll load the washing machine…, mop the floor, tidy up their bedrooms, put away clothes, then go to work. But they {children] don't see that; he cooks them dinner in the evening and they appreciate him. (Caribbean mother of children aged 10 and 7; husband works early shifts; she works afternoons and evenings)

Quote 10 If I'm not getting home 'til 8, I'm not picking them up 'til 7, coming in and then having to sort things out. …. The little one [aged 6] will pick up a book for himself now, he enjoys his reading, but he likes to have that half an hour of your time [to read him a bed-time story], which is right. I know things like that have fallen by the wayside. So I think that is stressful for me, because I don't feel I'm doing right by them I guess. (White English mother, just returned to full-time work in a demanding professional job)

Quote 11 The weekends are very much our time because we just don't get it through the week. And the spare time with him is at the weekends. (Mother of eleven year old in white English professional couple, both employed full time)

Quote 12 I have never had a day of my holiday when he hasn't also been there. And that doesn't sound at all maternal, and at all putting your child first, but most people can take a day off work even when their child's at school and have a day to themselves. (White English teacher, mother of eleven year old)

Quote 13 We [went to restaurants by ourselves] a bit more when he was younger, whereas now he can come to restaurants and things with us. It is actually nice to go out as a family, because we don't get so much of that time anyway. Mum and Dad say, if you ever wanted to have a holiday on your own we'd have him for a week' but we both feel that's not what a holiday is about. (Mother of eleven year old in white English professional couple, both employed full time)

Quote 14 I had a lovely day off the other Sunday. I just went up to London on my own and left you two [husband and son – the latter not present]. But when, in the evening, it would be nice to just think, oh I'm going swimming, oh no, I can't because T's in bed and D [husband] is not home. (Mother of eleven year old in white English professional couple, both employed full time)

Quote 15 He's alright, he's like me, we just chill out, I love films and he sits there, I love Disney films as well, and he just sits there…he just sits in my lap and he nods off and I put him to sleep too, but I like, I enjoy that time cos it's me and him so it balances the time I'm not there (Asian warehouse worker, father of two year old; group 2)

Quote 16 Half term's coming up and I've scheduled a whole week to be with them, it's more focused, it's more quality time I think, so in many cases they get the best of both worlds, they may not get their parents both together but they get a good time with their mum and a good time with their dad, so I would agree that that's why there is more time spent in childcare [than in previous periods] (Caribbean father, office worker; group 3)

Quote 17 There's something called paternal instinct. When my son was very unwell no matter how tired I was feeling I just had to do it, I was there for him, sometimes he kept me up all night, but it's that paternal instinct which you have and that closeness you've got, even though my son doesn't live with me full time now but I was with them at the early stages of their life, for the first few years and you do find that strength to just do that. (Caribbean father, office worker; group 3)

Quote 18 I think part of childcare is when you do homework together; you spend time in front of the PC, although it's homework it's quality time… I'll be sitting at the side and if they're stuck they'll ask me… so it's still part of childcare even though he's doing his homework, (Caribbean father, office worker; group 3)

Quote 19 Obviously however angelic your child is, after five days of looking after them you just want a break from them for the weekend. And hence the reason why fathers are spending a lot more time now looking after the children as and when they can (White English father of one two-year-old, office worker, group 4)

Quote 20 There's a certain amount of pressure on the father about the weekend and also during the week I feel, to play a more active role in the childcare and I think…maybe one of the reasons there's more time on childcare from both the parents is partly, like from eight upwards, at weekends or during the summer I'd just take myself off round the corner to my mate's or go and play football somewhere on me own, whereas now that's not acceptable practice, it's deemed unsafe for the child to do that. (White English father of one 4-year-old, manager, group 4)

Quote 21 At the weekends I always try to do something vaguely special even if you've done it before, take them out somewhere, do something, I think also, cos my wife works on Saturdays, so that's really our day where we go and do whatever we want to do but it's, it's not, I'm trying to think of the phrase rather than use that revolting phrase 'quality time' but it's like you're just trying to pack in as much as you can into the short space of time that you've got, just to make it entertaining (White English father of one 2-year-old, manager, group 4)

Quote 22 a) For some of this informant's friends, childcare is a chore:- I've got quite a few friends who have got kids and they maybe they've got the kids with them but they don't actually pay any attention to the kid, you're either just dragging a pram along or just walking…b) But for the informant himself, it's an important period to give children attention and talk to them:-

…but actually to spend time by talking, that makes more of an impression on a kid and you actually build a big relationship while doing it, obviously when they're young you can't start talking away to them and have them understanding, but sometimes you go out, sometimes we get a DVD, sometimes we just sit around or we're just hanging out so it's a variety of things, but I think it's more being a parent interested in your kid rather than just taking care of your kid, it's valuable time, I just use it in that sort of way (Caribbean father of two children aged 2 and 5, youth worker, group 4)

Quote 23 My daughter [aged 4] has a couple of problems with her speech so I make the time, of an evening, have a bite to eat, take them up to bed, always make the effort to talk about the day, to see what's she's done, to try, to spend good quality time with her and try and bring her speech on (White English father, manager, group 4)

Quote 24 I'm self employed so if I took time off then I wouldn't get paid for it. If my children are sick then I get phoned up first cos I can get there quicker than my wife can, then the other week I had to go home three nights at quarter past three to pick the kids up from school instead of five o'clock, I did it `cos the person who picks them up couldn't do it, and I lost money for it, but the pressure's still there to pay the bills at the end of the month… It's forced childcare isn't it, it's not enjoyable, you're being called out on an emergency… (group 1; taxi driver, father of two children aged 7 and 5)

Quote 25 I cook and I pick the kids up from the child minder …I end up cooking for the kids five nights a week and my wife don't …she works part time so I have to do the night thing and I tidy up the house, if I've got two or three hours to do it when I'm minding the children then I do all the cleaning and washing, someone's got to do it. I do it all and I think it's sad, cos it wouldn't have happened years ago, if my wife was at home all the time not working… (group 1, voice not identified, low paid manual worker with long hours)

Quote 26 I do see mine but not a lot, I don't see them as much as I'd like, it's like when the family have a little gathering, sometimes I have to work so they have to be without me. You feel left out, like you're missing out don't you? (group 1, voice not identified, low paid manual worker with long hours)

Quote 27 My daughter's only ten months old so right now I'm going to spend all the time I can with her (group 2; office cleaner, white English father of one)

Quote 28 Saturday and Sunday, she's working, I'm not seeing her [partner], I'm holding the baby…the last thing I want to do when I've done all these hours, I'm doing like sixteen hours a day [Monday to Friday] is to come home and have my boy to look after (self-employed construction worker, son aged 2; group 2)

Quote 29 You just get to know them as little people, then you've got to leave them with someone else – I used to hate it. Work was another stress. I started to ask, didn't I have a child to enjoy my children ? I got a part time job closer to home. That was nice, up at a decent hour, take J to nursery 9.30 to 11, then a friend took him for the rest of the morning. We had the rest of the day together, my son and I – that was nice. (Caribbean mother of 15 year old son and 11 year old twin daughters; husband had also `downshifted' to a less stressful job with shorter hours to be more with the family).

Quote 30 You need time with children for them to say what's wrong. A lot of my friends say they haven't noticed a problem with underlying things. Children have more of a need for you in this way when they are older. Then, it's more difficult to get to the bottom of it. They don't necessarily chat about their problems at all – it comes out indirectly. (same informant as quote 31)

Notes

1Analysis here is confined to parents of under 12s, since once the youngest reaches 12, at least 20% of families record no `primary' parental childcare on either diary day.2Defined as less than half the average of disposable time free of paid work and caring

3See Sly, 1994, for earlier data and Walling, 2005, for data since 1994.

4See table D7242 (`Travel to School') available from http://www.statistics.gov.uk, accessed 31.3.06.

5Analysis of variance tests show this finding is significant at the 0.01 level

6 The data for childcare by each parent are calculated using the concept of a couple-week. The father's two one-day diaries were linked with the mother's two; then by multiplying each parent's time in work, childcare or any other activity on the weekday by five and adding that to twice the corresponding amount on the weekend day, we obtain an estimate of weekly time use. This is a well-accepted method in time use research. After trials of several transforms to find a mathematical representation of the dependent variable which is normally distributed, the raw variable was transformed into its square root to normalise the distribution; thus the equation is not linear in the actual childcare time, but linear only in its square root.

7A significant difference with p=0.001 (chi squared = 36.973)

8F = 17.416; p<0.0005

9F = 4.325; p=0.038.

10P=0.013; F=6.178

11Warren uses the parental questionnaires of the British Household Panel Survey, and Ferri and Smith (discussed earlier) the National Child Development Study.

12Author's analysis of the Labour Force Survey. The variable used here is total work in the reference week, including overtime whether paid or unpaid and also work in any second job.

13Author's analysis of the Labour Force Survey

1449% of all Danish women worked full-time in 2001 compared to Britain's 36% (European Commission 2004)

15The rapid growth of part-time pre-school places since then has induced some increase in mothers' employment, but their daily duration is too short to permit mothers to take jobs without additional childcare support (for further discussion see Gray, 2005).

16Weekday work hours of all women and men in working age couples average 6.24 and 7.87 respectively, compared to 3.82 and 6.96 in the UKTUS.

References

BIANCHI, Suzanne (2000) `Maternal Employment and Time with Children; Dramatic Change or Surprising Continuity?' Demography, Vol. 37, no.4, pp. 401-414

BITTMAN, M. (1999) An International Perspective to Collecting Time Use Data: paper presented at the Committee on National Statistics Workshop on Measurement of and Research on Time Use, Washington, D.C.

BITTMAN, Michael (2002); `Social Participation and Family Welfare; the Money and Time Costs of Leisure in Australia', Social Policy and Administration, Vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 408-425.

BITTMAN, M. (2004a) Parenting and Employment, in Folbre, N. and Bittman, eds., Family time; the Social Organisation of Care (London: Routledge)

BITTMAN, M. (2004b) Parenting without penalty, in Folbre and Nelson, see above.

BITTMAN, M. and Wajcman, J. (2000) `The rush hour; the quality of leisure time and gender equity', in Folbre, Nancy, and Bittman, Michael, eds, op.cit.

BITTMAN, M., Craig, L. and Folbre, N. (2004) `Packaging care; what happens when children receive non-parental care?' in Folbre, N. and Bittman, M., eds., op. cit.

BOURDIEU, P. (1986) The forms of capital, in Richardson, J.E. (ed) Handbook of theory for research in the sociology of education (Greenwood Press, Westport, CT).

BRANNEN, Julia (2005) `Time and the Negotiation of Work–Family Boundaries: Autonomy or illusion?' Time and Society Vol, 14, no. 1, pp 113 - 131.

BRUEGEL, Irene, 2004; In what sense is childcare shared between parents? Paper to the International Work-Life Balance Conference, Edinburgh, 30 June - 2 July 2004.

BRYANT, W.K. and Zick, C.D.(1996) `Are we investing less in the next generation?' Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 365-91

CALDERWOOD, L., Kiernan, K., Joshi, H., Smith, K, and Ward, K (2005) `Parenthood and parenting' in Dex, S. and Joshi, H., eds., Children of the 21st Century. Bristol; Policy Press.

COLEMAN, J.S. (1988) `Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital', American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 94, Supplement, pp. 95-120.

CROMPTON, R., Brockmann, M., Lyonette, C. (2005) `Attitudes, women's employment and the domestic division of labour' Work, Employment and Society vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 213-233

DALLA COSTA, Mariarosa (1973); `Women and the Subversion of the Community', in M. Dalla Costa and S. James (eds) The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community. Bristol: Falling Wall Press.

DEDING, Mette and Lausten, Mette (2004); Choosing between his time and her time? Market work and housework of Danish couples, mimeo, Danish National Institute of Social Research.

DEX, Shirley (2003) Work and family life in the 21st century. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2004) Employment in Europe

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2005) Integrated Guidelines for Growth and Jobs 2005-8. Luxembourg: European Commission.

FAGAN, C. (2002) `How many hours? Work-time regimes and preferences n European countries' in G. Crow and S. Heath (eds) Social Conceptions of Time; Structure and Process in Work and Everyday Life. London: Palgrave/Macmillan.

FERRI, E. and Smith, E. (1996) `Parenting in the 1990s'. London: Family Policy Studies Centre.

FISHER, K., McCulloch, A. and Gershuny, J. (1999) British Fathers and Children. working paper, Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex.

GAUTHIER, A., Smeeding, T. and Furstenberg, F (2004) `Do we invest less time in children? Trends in parental time in selected industrialised countries since the 1960s' Population and Development Review, Vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 647–671.

GERSHUNY, J., (2000) Changing times; work and leisure in post- industrial societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

GERSHUNY, J., and Sullivan, O., (2001): `Cross-national changes in time-use; some sociological (hi)stories re-examined', British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 52 , no. 2, pp. 331-347.

GERSHUNY, J., Godwin, M and Jones, S, (1994): `The domestic labour revolution; a process of lagged adaptation', in Anderson, M., Bechhofer, F and Gershuny, J, eds., The Social and Political Economy of the Household. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

GRAY, Anne (2005) `The Changing Availability of Grandparents as Carers and its Implications for Childcare Policy in the UK'; Journal of Social Policy 34/4, 557-577

HIMMELWEIT, Sue : (1995): `The discovery of unpaid work; the social consequences of the expansion of work', Feminist Economics, Vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1-20.

JENKINS, S. and O'Leary, N. (1997) `Gender differentials in domestic work, market work and total work time; UK time budget survey evidence for 1974/5 and 1987', Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 153-164.

KILKEY, Majella (2005) `New Labour and reconciling work and family life; making it fathers' business?' Social Policy and Society vol. 5, no. 2, pp 167-175

KITTERØD, Ragni H. (2002); `Mothers' Housework and Children; Growing Similarities or Stable Inequalities', Acta Sociologica , Vol. 45, no. 2, pp 127-149.

KODZ, J. (2003) Working long hours; a review of the evidence: Employment Relations Research Series no. 16. London: Department of Trade and Industry.

LAYTE, Richard (1999) Divided Time, Gender, Paid Employment and Domestic Labour, Ashgate, Aldershot .

MORROW, V. (1999) Conceptualising social capital in relation to the well-being of children and young people: A critical review, The Sociological Review, Vol. 47(4), pp. 744-765.

O'BRIEN, M (2004) Shared Caring; Bringing Fathers into the Frame. Manchester; Equal Opportunities Commission.

O'BRIEN, M. and Shemilt, I. (2003) Working Fathers; Earning and Caring. Manchester: Equal Opportunities Commission.

OAKLEY, Anne (1974); Housewife. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

OECD (2001) `Balancing work and family life; helping parents into paid employment' Employment Outlook 2001, Chapter 4, pp. 129-66

PERRONS, Diane (2000) `Care, paid work and leisure; rounding the triangle' Feminist Economics Vol 6., no. 1, pp. 105-114

PILCHER, Jane (2000) `Domestic divisions of labour in the 20th century; change slow a-coming' Work, Employment and Society, Vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 771-780

PUTNAM, R.D. (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (Simon and Schuster, New York).

SANDBERG, John and Hofferth, Sandra (2001) `Changes in Children's Time with Parents; United States 1981-1997', Demography, Vol. 38, no.3, pp. 423-436.

SAYER, L., Bianchi, S. and Robinson, J.P. (2004); `Are parents investing less time in children?' American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 110, no.1, pp. 1-21.

SCHOON, I. and Hope, S. (2004) `Parenting and parents' psychosocial adjustment' in Dex, S. and Joshi, H. (eds) Millenium Cohort Study first survey; a user's guide to initial findings'. London: Centre for Longitudinal Studies.

SMEATON, D. and Marsh, A. (2006) Maternity and Paternity Rights and Benefits; Survey of Parents 2005, Department of Trade and Industry Employment Relations Research Series no. 50, accessed on http://www.dti.gov.uk, 18.4.06

SLY, F (1994) `Mothers in the Labour Market', Employment Gazette vol. 102, no. 11, pp 403-420.

VAN DE LIPPE, T. and de Ruijter, E. (2004) `The increase in time spent on children by mothers and fathers'; paper for the conference Work-life Balance: Across theLife Course, University of Edinburgh, 30 June – 2 July 2004

WALLING, A (2005) `Families and Work', Labour Market Trends, online edition at <http://www.statistics.gov.uk>, July 2005, pp. 275-283.

WARREN, Tracey (2003) `Class and gender-based working time? Time poverty and the division of domestic labour' Sociology, Vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 733-752.