Oyster Coverage: Chiastic News As a Reflection of Local Expertise and Economic Concerns

by Toby A. Ten Eyck and Forrest A. Deseran

Michigan State University; Sonoma State University

Sociological Research Online, Volume 9, Issue 4, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/9/4/9/4/ten_eyck.html>.

Received: 9 Mar 2004 Accepted: 24 Nov 2004 Published: 30 Nov 2004

Abstract

The media, it is argued, are agents of legitimation - for themselves as well as others. Issues and social actors become recognized as important when they appear within the limelight of the news, and reporters are relied upon to correctly choose among the myriads of issues and actors vying for their attention. What happens, though, when an economically important cultural icon becomes a health threat? This is the situation facing news organizations in Southern Louisiana where oysters are both loved and loathed as food. We study newspaper presentations of oysters in Southern Louisiana over a ten-year period to investigate the ways in which this issue was approached. In many of the instances when negative articles appeared, positive statements could be found in the same issue of the newspaper, creating what we refer to as chiastic - defined as two parallel lines moving in opposite directions - media presentations. The presence of this type of news reporting is discussed in terms of the economic and cultural importance of the oyster, the economics of newspapers, and the stance of news organizations as cultural authorities.

Keywords: Chiastic, Culture, Economics, News, Oyster

Introduction

"Pleasure's a sin, and sometimes sin's a pleasure" - Byron1.1 A good deal of attention has been aimed at understanding the role of public arenas in the construction of social problems (Hilgartner and Bosk 1988; Lange 1993;Ungar 1992). Our aim in this paper is to explore the dynamics of a public arena when an economically important cultural icon becomes a health concern to see if such a threat leads to the generation of opposing or contradictory stances - what we refer to as chiastic news. According to The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (1996), chiasmus (chiastic is the adjective form) is a literary device or figure of speech by which the order of the terms in the first of two parallel clauses is reversed in the second. This may involve a repetition of the same words or just a reversed parallel between two corresponding pairs of ideas. An item or identity which provides both threats and promises may lead to such public discourses, so we look to public arenas as sites where conflicting narratives may be found. We extend the argument of the multifaceted nature of the mass media to include the role of vested interests in story development through the mobilization of legitimate authority among news organizations (Zelizer 1992), and the need for local news organizations to protect their own economic interests (Franklin and Murphy 1998). Our examination of presentations within this environment involves the coverage that a major daily newspaper has given to an important cultural element in Southern Louisiana -- the oyster.[1]

1.2 The motivation for such an undertaking stems from a concern with the ways in which an organization within the cultural industry would react to something that, on the one hand, threatens individuals (the risk of eating a tainted oyster) and, on the other, threatens society (concerns with consuming oysters could lead to a collapse of the oyster industry). If the organization decided to ignore a threat which readers were aware of, it might lead to a loss of credibility and readership. If, however, the organization decided to focus on the threat, it may lead to a loss of advertising from industries supported by oysters, such as processing plants and restaurants. With conflicting information and conflicting goals, we were curious if this would lead to conflicting reports from the organization. We begin with a background of media organizations.

The Economics and Expertise of Local News Organizations

2.1 Our theoretical perspective stems from a concern with the meanings of content within a public arena, and what, if any, factors based on the practices of those maintaining the arena would predict an outcome such as chiastic presentations. The argument being put forth here is that symbols are ideological, and their meanings can change as they move from sender to receiver (Thompson 1990), though senders have some control over what symbols will be employed. This is especially true of the mass media, as reporters and editors have some time to think about how a story will be developed (e.g.,Inglis 1990;Price 2002). In addition, media information is used to help make sense of issues (Gamson 1992), and it has been found that the presence of the media has some use in predicting political unrest (Ten Eyck 2001). This still does not explain the emergence of contradictory coverage, but does highlight the need to study it as both an outcome of the practices of a news organization and as information being used by consumers. Studies which can shed light on this phenomenon should focus on two aspects of the news - the economics and authority/expertise of the news organization.2.2 Given that our focus is on a local newspaper, it is important to understand the nuances of this type of institution relative to large regional or national newspapers. Local newspapers, whether family-owned or run by large media conglomerates (see Bagdikian (1992)on the changing structure of local media ownership in the US), must satisfy local audiences and advertisers if they are to remain financially viable. According to Leather (1998), news writing has moved from thinking of readers as citizens to thinking of them as consumers, which is especially important for local newspapers as their financial success is tied to local advertising. When information is available which may threaten a local business, news organizations must decide how that information will be treated. Reporting that the operations of a local business are risky may result in the loss of advertising, especially if the business advertises with the newspaper.

2.3 Considering the business aspect of the organization does not mean the newspaper forgets about its audience, for without readers businesses would be unwilling to buy advertising, which translates into an expectation that reporters will produce stories that resonate for their audiences. One way to succeed at this is to develop within the audience a sense of significance for the news - for reporters to make themselves experts on local issues.[2] Zelizer (1992), for example, has argued that through synecdoche, omission, and personalization, reporters were able to place themselves as the most credible experts on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Through her account of the ties between the Kennedy Administration and the media, Zelizer showed how reporters came to have a vested interest in a President willing to allow news reporters into his personal and professional lives - at least to some extent. His assassination was more than just a news event concerning a major public figure; Kennedy, who had worked as a reporter, was seen as one of their own, and coverage of his death helped galvanize reporters as experts on both the man (Kennedy) and the position (President of the United States).

2.4 Zelizer, however, investigated national or large regional news organizations, and studied a story which would resonate with most US audiences. Local newspapers, on the other hand, must carry stories which are locally situated in an economic context as mentioned above. Items deemed newsworthy but threatening to a local industry led us to investigate conflicting accounts of the same topic. This goes beyond the idea of objectivity in the news in which various sides of a controversial topic are presented in a single news article (e.g.,Tuchman 1978). Objectivity, in this sense, is about the professionalism of journalists. We were more interested in the positioning of a reporter and his/her news organization as an expert or authority on local issues. Understanding the economic landscape in which a news organization is situated is part of that positioning, but it also entails an appreciation of the nuances of the larger social landscape. This includes knowing what are important issues in an area, regardless of the economic ties involved (though the importance of an issue is often directly tied to economics). Ignoring details of a salient local issue, even those that are detrimental, is taking the risk of being labeled as uninformed (Ten Eyck and Deseran 2001), which would be a disastrous label for a news organization.

2.5 Chiastic reporting can happen in at least two ways - as a conscious effort by a news organization to protect economic interests and appear authoritative on an issue, or as simply a consequence of the ways in which news "happens." Murphy (1976), as well as others (e.g.,Gitlin 1980), contended that journalistic practices are not politically neutral. Reporters may try to be considered noncontroversial in the sense that their own role in bringing a story to light is not reflected upon within the final report, but is done in such a way as to present themselves as important to a local audience and advertising stakeholders. Reporters and editors within a news organization may understand the consequences of publishing a detrimental story on a local business or industry, but feel that the consequences of ignoring the issue would be even more damaging to the reputation of the news organization, which in turn could lead to fewer advertisers trusting the organization with their money.

2.6 Of course, chiastic coverage could be little more than coincidence given the amount of information made available to news organizations on a daily basis. There is evidence that conflicting reports on issues are not uncommon. Ten Eyck et al. (2001), for example, found conflicting stories concerning biotechnology. A topic such as golden rice, for example, would be introduced as a way to end vitamin deficiencies in developing countries, yet another article would contend that golden rice or other genetical modified crops were unwanted or detrimental to the environment and world development. Michael Crichton's concerns about big science and nanotechnology can be found side-by-side with stories about the wonderful new promises of this technology. Excitement over the Mars landings is paired with the astronomical costs of maintaining NASA. The list is nearly endless. If it is only a coincidence that all of these conflicting stories are appearing in near proximity, then news organizations may find it desirable to take advantage of knowing this, while public opinion researchers could profit from understanding audience reactions to various issues within the context of news development and dissemination.

2.7 Our topic of interest - the oyster - has come under fire over the past several decades. Objective news accounts which discuss the oyster reflect the balance and "sense" of news with regards to power relations between reporters and sources (Davis 2003;Ericson et al., 1989;Williams 1999). According to this line of work, the status of news and source organizations are not equal, yet reporters seek to include opposing voices in their reports. It becomes an empirical question to study the balance shifts when an important economic commodity and cultural icon becomes threatened. The oyster has received a fair share of coverage both as a "hard" news item (often in the form of a health threat) and as a culinary or cultural object. In Southern Louisiana, oysters are important economically and culturally, so while newspapers may feel compelled to report the negative consequences of consuming oysters, there is reason to believe that there is a vested interest in reporting any positive aspects of this shellfish as well. If news organizations failed to present these various aspects of the oyster, they may be questioned as legitimate informational and cultural authorities within the local community.

2.8 The notion of a health threat and the public brings to the fore concerns with risk communication. In the areas of food and health, negative media attention has been found to influence consumer decisions, usually evidenced by a drop in consumption of the product under question (e.g.,Hilgartner and Nelkin 1987;Powell and Leiss 1997). Sandman (1993), in his treatment of outrage and risk, has argued that lay members of the public think about their own ability to control potential risks, weighing the costs and benefits of either ignoring or taking seriously communication coming from experts. Their level of outrage is often tied to the amount of control they feel they have in a situation, or how much they think others can pacify their concerns. Many of the problems with oysters - pathogens, contamination from spills, heavy metals - are not detectable with "look, taste, and touch" approach to testing the quality of food, so it could be argued that such risks would be the bases for outrage. The oyster in Louisiana, however, is also a cultural icon, as we explain in the next section.

Oysters in Louisiana

3.1 Oyster harvesting is one of the oldest and most well-established components in Louisiana's seafood industry (see http://www.wlf.state.la.us/apps/netgear/index.asp?cn=lawlf&pid=1084 for a brief history of the Louisiana oyster industry). Due to geographical advantages and the large amount of privately controlled harvesting areas or grounds, the Louisiana fishery became the nation's largest producer of oysters by the 1980s (Keithly and Roberts, 1988). Despite Louisiana's leadership in oyster production, local harvesters face an array of problems that cloud the future of the industry. Similar to other commercial seafood fishermen operating out of Louisiana, oyster harvesters have been adversely affected by pressures from environmental disturbances, increases in the costs of equipment and operations, a rise in the amount of imports, and increasingly rigid regulatory demands.3.2 The most pressing crisis for the Louisiana oyster industry during the period covered by our research was a series of deaths attributed to a bacterium (Vibrio vulnificus) that develops in oysters. This led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to propose a ban on the sale of raw oysters (McKinney, 1994). Industry spokespersons estimated that such a move would put at least half of the harvesters out of business (McKinney, 1994). Although a comprehensive ban on oyster production has not occurred to date, the threat left a pall over the industry.

3.3 The economic importance[3] of oysters is only one reason why we consider oysters a key component of the Southern Louisiana culture. Visitors to South Louisiana, especially New Orleans, cannot escape the presence of the oyster. Oyster bars in the French Quarter are among the most well known restaurants in the city. Oysters adorn bumper stickers, post cards, T-shirts, and even men's ties. For many, a bottle of Dixie Beer and a dozen oysters on the half shell epitomize the South Louisiana experience. This role of food should not be trivialized as studies have found that food is widely used in the construction of social boundaries. In Peru and Bolivia, for example, beer and chicha are used to demarcate different situations (Orlove and Schmidt 1995). In Mexico, TV dinners are mainly consumed by those in the upper classes, and wheat and wheat products are symbols of prestige (Pelto 1987). Organic food has been used by some groups to demarcate their standing as a counterculture (Belasco 1993). In short, once survival needs have been met, food stuffs are likely to become symbolic/cultural resources used to define cultural practices and social groups. If these cultural icons are threatened, some will mobilize to defend them.

3.4 The dualistic image of oysters - as a health threat on the one hand, and cultural icon on the other - offers us an opportunity to investigate the patterns of media presentations of these conflicting depictions. If we begin with the idea that a cultural element embodies vested interests or sunk costs (emotional and/or economic), then we would expect those who have ties to such a cultural element to defend it when attacked or called into question. We argue that local media outlets (as opposed to national syndications), as transmitters of cultural information for a specific locality and tied to the economic interests of that locality, will have affinities toward cultural items they feel are important to their audience. The notion of risk communication in this sense is twofold -- 1) risk to the health of the reader, and 2) risk to the economic well-being and expert standing of the news organization.

A Caveat on the News

4.1 Our argument rests on the notion that a story presented in a newspaper will carry some weight for readers - there will be some notion that it is a legitimate story if it is noticed. We do not contend that a review for a new raw oyster bar on page four of the Food section has the same significance as a front page story about the death of a restaurant patron. At the same time, there is some evidence that feature stories are important. Winthrop (1972) used both hard (e.g., a news story on discrimination) and soft (e.g., a feature story on African-Americans in the movies) news to study students' understanding of social issues, and Peterson and Kern (1996) have argued that individuals within the upper classes of US society are becoming more omnivorous in their leisure tastes, so must be aware of the human interest stories around them. In short, while we are aware of possible concerns that featured stories are being lumped together with news stories, we do not want to weigh one more than the other based on assumptions of how readers interpret the news, as we did not conduct public opinion surveys on this topic. The question is whether or not conflicting stories are appearing in close proximity in the same news source.Data Source

5.1 News coverage and discussions with oyster harvesters had led us to believe that the oyster industry had been threatened by numerous concerns with bacteria, viruses, and accidental spills of contaminants, yet the oyster was still a popular food item in Southern Louisiana. We conducted a content analysis of a local newspaper, which, according to Stempel (1989) should be concerned with manifest content first, and interpretation second. Manifest content, though, can be problematic (Garfinkel 1967), as some images and symbols are more powerful than others depending on the content and context of both message development and reception (Gamson 1992). We included both hard news and soft news in our analysis knowing that these types of stories can have varying levels of impact, though recent studies are finding this division to be somewhat overstated (Baum 2003). Our data are from The Advocate, the major daily paper serving Baton Rouge, Louisiana (http://www.theadvocate.com). This newspaper is appropriate for our purposes for several reasons. It serves a readership that is geographically situated in the southern part of the state where seafood, including the oyster, is an important part of the local cuisine. Because Baton Rouge is the state capitol, the site of two major universities, and the second largest city in Louisiana, the paper has a relatively diverse readership and offers a wide variety of news and features. In addition, The Advocate is locally owned and operated, which enhances the relevance of the local cultural context.5.2 We searched for all articles over a ten-year time span (1986-1995)[4] that mentioned oysters, uncovering over 1000 articles in which oysters were discussed, varying from being the focal point of the article to no more than a brief mention. For the purposes of this paper, we refer only to those articles that dealt with oysters as a food item - positively and negatively slanted (N=322). We did not include in our sample articles dealing with other aspects of the oyster industry, such as leasing policies, licensing issues, damage to oyster grounds due to coastal erosion, and so on. In addition to general tendencies in presentations, we attempted to discern factors which may lead to various types of presentations within the newspaper, couching these within our argument that newspapers are local authorities with regards to culture.

Measuring Chiasmus

6.1 We calculated instances of chiastic presentations by estimating the total possible number of times that a positive and a negative article could appear within a specified time frame. Given that negative articles appeared with less frequency, the total possible number of instances was determined by the number of negative articles with reference to oysters as food (N=79). While judging the contradictory nature of the content of two stories is relatively straightforward, the temporal dimension of chiastic presentations is more problematic. It is evident that close temporal proximity of news stories covering the same subject could contribute to readers' and journalists' awareness of those other related articles[5]. However, the rate with which this cognizance dissipates over time is not evident. Work on the knowledge-gap hypothesis (e.g.,Chew and Palmer 1994) indicates that this will be contingent on the importance the issue has for the audience member. Work on public perception of biotechnology, for example, found that nearly ten years after its release, Jurassic Park -- The Movie was still being used to make sense of new information on genetic engineering (Gaskell and Bauer 2001). If an issue is considered consequential, it is hard to define a time line for when a specific presentation of that issue will be forgotten or transformed. At the same time, we do not want to overstate the power of the media to hold the attention of the audience. It was felt that an appropriate length of time would be 30 days, though we also investigate articles appearing at much shorter intervals.Prevalence of Chiasmus

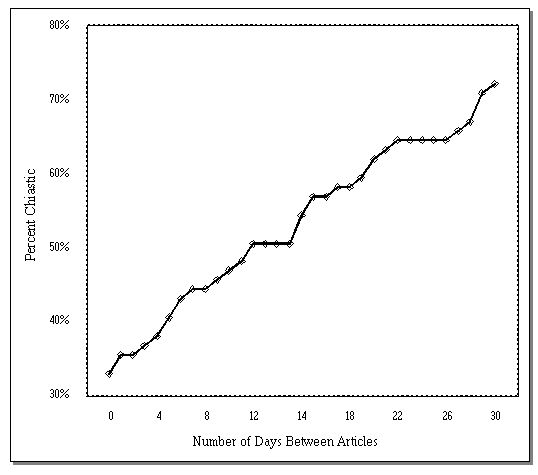

7.1 In Figure 1 we report the percent of chiastic occurrences by the number of days between stories. Over 30 percent of all negative stories about oysters are accompanied on the same day by stories that portray the consumption of oysters in a positive light. Understandably, the percent of chiastic presentations increases as the span of days we use to define chiasmus is increased, with about half of the total possible incidences occurring within a 12-day span and up to 70 percent at 30 days. These findings leave little doubt that the coverage of oysters in Louisiana is characterized by a dualistic discourse, as the newspaper-- as a cultural mediator and embedded within an economic milieu where the oyster is important -- is being confronted with conflicting messages and cannot ignore the conflict.

|

| Figure 1. Percent of Total Possible Chiastic Occurrences by Number of Days between Stories |

7.2 Our findings that chiastic presentations of oysters were common between 1986 and 1995 direct our attention to factors that may influence the prevalence of these types of presentations. Toward this end, we will consider those factors that are outcomes of editorial decisions concerning media presentations using statistical procedures. The hierarchical nature of most newspapers, including The Advocate, implies that while reporters might be writing stories about the pros and cons of an issue, editors are then making decisions on which stories to run (e.g.,Gans 1979). Their actions are as telling as the words which appear in the newspaper. We should note that the interpretations of our findings are based on knowledge of news organizations, and not on ethnographic data which would offer additional insight for such a study. As mentioned, this chiasticity may be simply a matter of coincidence, though finding examples of it over a decade does say something about journalist practices and the positioning of readers on the issue.

Characteristics of News Presentations and Chiasmus

8.1 One of the major assumptions of this study is that reporters and editors at newspapers have some inkling of the content of their product, though we also know that coordination among the various units is not absolute (e.g.,Gans 1979). What was not clear was to what degree certain practices would be correlated to chiastic coverage. To investigate these linkages, we focused on the following factors: prominence of display (which includes headlines, placement, and space); the distinction between news articles and opinion columns; and whether or not the source of the story is from an external news service (i.e., wire service).8.2 The prominence with which stories are displayed in the printed news is of particular interest as the construction of news does not take place in a vacuum but reflects editorial judgments and vested interests. In general, we suspect that prominently displayed topics are not only an outcome of specific editorial decisions but involve mutual decisions within the news organization (Tuchman, 1978). Consequently, we expect that the higher the prominence of the presentation, the lower the likelihood of chiastic presentations, as threatening a prominent story within the organization may lead to questions of legitimacy by the audience. Previous studies on news presentations have identified three key dimensions of prominence that we incorporate in our study -- headlines, article placement, and space allocation. Headlines have been found to reflect the editorial decisions about what constitutes the most important contents of a news story (Chaudhary, 1980;Parenti, 1993;Turk, 1979), while placement is probably the most common method of establishing the importance of a story in the print media (Parenti, 1993). Specifically, editors consider front page articles to be the most important or interesting (Chaudhary, 1980;Luebke, 1989;Paletz et al., 1980;Salwen 1988). Finally, the space given to an article has been found to reflect editorial decisions regarding the perceived salience of that article (e.g.,Ader, 1995;Crelinsten, 1989;Pfund and Hotstadter, 1981).

8.3 In addition to the prominence of stories, we distinguish between news stories and columns (or opinion pieces). Binder (1993:757) notes that columns represent the most open expressions of subjective opinion in a news publication. As such, columns tend to mirror editorial biases, especially with regard to objects of local cultural interest such as Louisiana oysters. The likely effects of columns on chiastic presentations are not clear. Columns about oysters may increase overall editorial awareness, thus contributing to greater efforts to maintain consistent presentations (i.e., decrease the likelihood of chiasmus). Conversely, columns may be stimulated by negative news stories about oysters as local writers try to protect local interests, thereby increasing the likelihood of chiasmus. This highlights the two sides of the news organization as local authority and the protection of economic interests. First, readers would expect a newspaper to be consistent in day-to-day coverage, and to be linked to the local culture and economy. The sway of these conflicting forces will be shown, at least partially, in the degree of chiastic reporting.

8.4 A large proportion of the stories appearing in the printed news media are from wire services (e.g., AP, UP). As with columns, the effect of wire service stories on chiastic incidences is not clear. On the one hand, it is possible that wire service stories lend external legitimation to the significance or interest appeal of a local issue, thereby increasing organizational consciousness of the issue. This would result in lower levels of chiasmus. On the other hand, wire service articles may be perceived as reflecting the viewpoints of individuals from organizations which are not privy to the innuendos of local issues or levels of local interest. In the latter case it is possible that instances of chiasmus would increase following wire service stories generated by distant organizations concerning a local cultural element.

8.5 We include the month in which articles are published to control for variations that may be due to seasonal biases. Because oyster production and consumption are seasonal, with peaks during the holiday months that occur between November and February (Thanksgiving through Mardi Gras), we control for articles appearing during these months. In addition, to examine possible interaction effects between the evaluative direction of articles and our major variables, we run a separate analysis which includes a variable which distinguishes between negative and positive presentation of oysters.

Analysis and Results

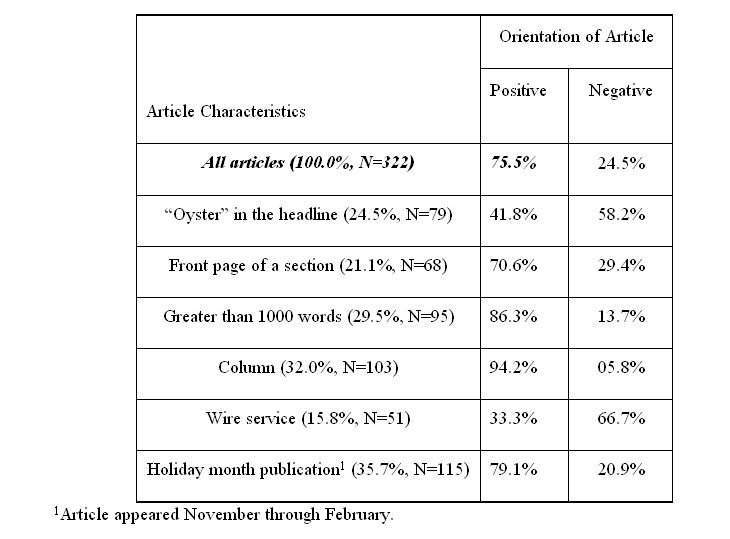

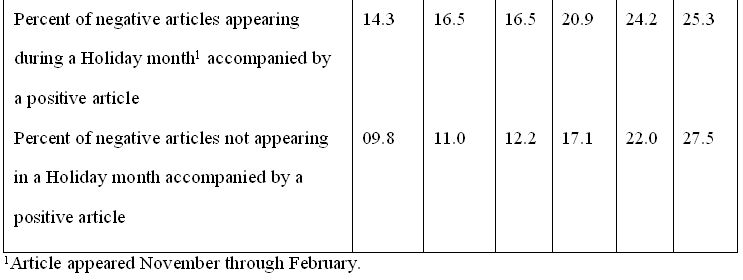

9.1 Table 1 shows the distribution of characteristics among the sampled articles as well as a breakdown of the percent of positive and negative presentations. Of the 322 stories in our sample, we found that about one-fourth of the stories were accompanied with the word "oyster" in the headline, one-fifth of the stories were on the front page of a section, and almost one-third were written as columns. Wire service articles accounted for about 15 percent of our sample, indicating that most stories were written by local reporters, who we would expect to see themselves to be one of the groups of experts on this issue in the local community. The relatively large proportion of local and commentary articles is consistent with our argument that oysters have a high economic and cultural salience in Louisiana. The proportion of articles that appeared during the holiday months (November through February) is only slightly higher than other months. Just over one-third of the articles appeared during these months, giving us reason to believe articles focusing on oysters were not confined to certain months.| Table 1. Percent of Negative and Positive Newspaper Stories by Article Characteristics |

|

9.2 Turning to the positive/negative valence of the articles, the popular opinion (at least amongst those associated with the oyster industry) that most media presentations of oysters are negative is shown to be false; more than 75 percent of all articles were positive. The perception of negative reporting, though, could be an outcome of prominence factors. In this regard, we found that negative articles were disproportionately accompanied by headlines with the word "oyster," although more positive articles appeared on the front page of various sections. In addition, over 85 percent of the positive articles contained over 1000 words. Finally, Table 1 shows that columns were disproportionately positive while wire service articles were largely negative, and a majority of articles published during the holiday months (November through February) were positive. The fact that most of the wire service articles were negative is consistent with the notion that outsiders would be more likely to attack oysters, while positive, culturally-relevant articles would be generated from within the community. This is not to say that all local stories were positive, perhaps reflecting the editorial belief that ignoring possible threats could be detrimental to the status of authority. However, disregarding the role of the oyster in southern Louisiana because of negative publicity, especially if it was generated outside the community, could also be considered a transgression against local vested interests.

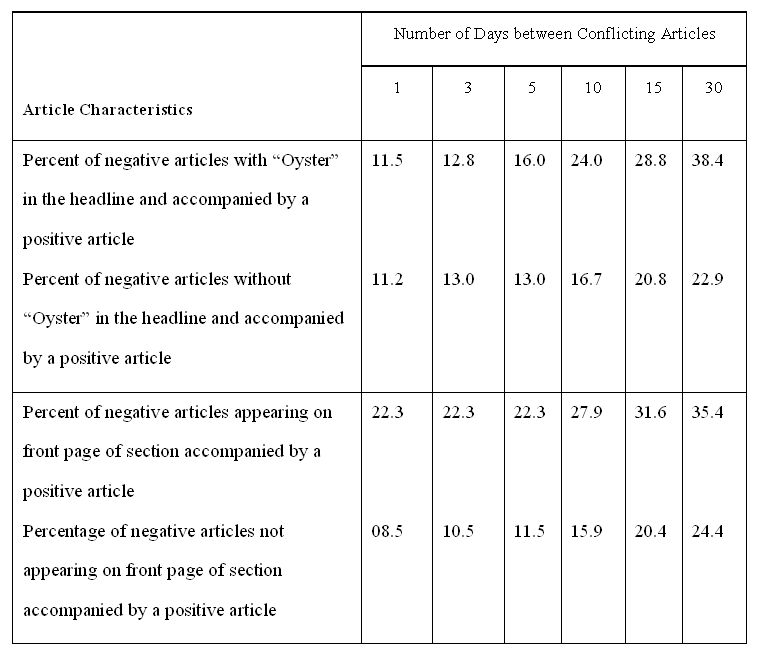

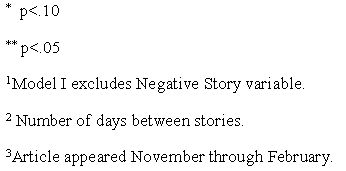

9.3 Table 2 contains findings for zero-order relationships between instances of chiastic reporting and the major predictor and control variables. In this table we report the breakdown of news articles by our model variables and the percent of chiastic occurrences within specified time frames ranging from one to thirty days. The findings are based on the 79 negative articles found in this ten-year time frame.

| Table 2. Percent of Chiastic Occurrences of Newspaper Stories about Oysters by Article Characteristics within Selected Numbers of Days between Articles |

|

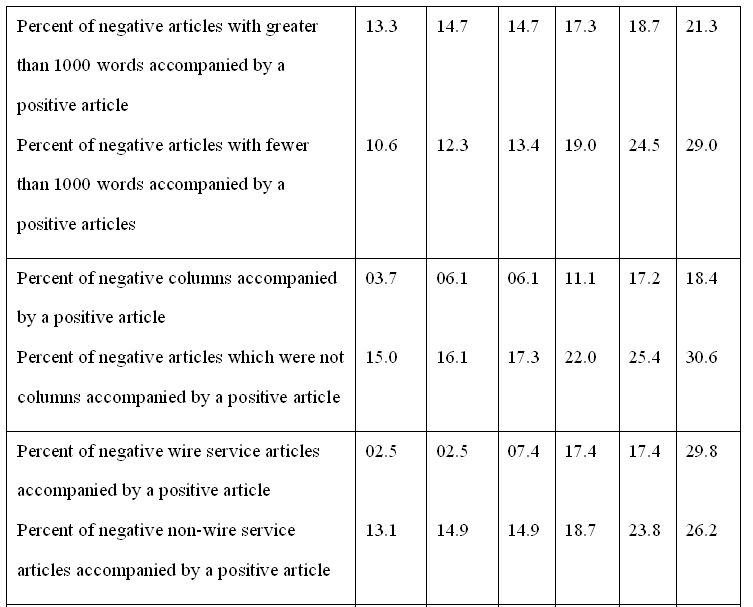

9.4 We present separate findings for specified time frames largely because we know of no clear parameters for defining temporal proximity in the publication of stories. The first column in Table 2 contains findings for all articles within a one-day time span, the second column contains findings for a three-day time span, and so on, up to 30 days. The distribution of percentages reported in Table 2 indicates the extent to which our model variables may have an effect on chiasmus. Of the characteristics related to the prominence of stories, front page placement yields the greatest variation in percentages of chiasmus. For the one-day time span, more than 22 percent of the stories appearing on the front page of a section were accompanied by contradictory articles, compared to only 8.5 percent of stories that do not appear on a front page. This difference holds as the number of days between articles increases. The findings for articles with "oyster" in the headline or for the size of articles show much less variation, especially in the narrower time spans.

9.5 Our next two variables, articles published as columns and wire service articles, resulted in marked differences in the percent of chiastic publications and both were associated with a reduced likelihood of chiasmus. For the one-day time span, only about 4 percent of all column articles and 3 percent of wire service articles were accompanied with contradictory articles, compared to 15 percent and 13.1 percent respectively for articles that were not columns or furnished by the wire services. These differences hold across different time spans for columns, but for wire service articles we find fewer marked differences as the time span increases. Finally, turning to our holiday variable, our findings show that presentations during holiday months are somewhat more likely to be chiastic than those presented during other months (14.3 vs. 9.8 percent).

9.6 The finding that wire stories were not accompanied by local stories is somewhat surprising at first glance. After all, and as we have argued, one would expect a local authority to voice concern in the face of damaging outside commentary. However, given the need for consistency, it may be that outside stories are given more weight, therefore attenuating the need for prominent local stories. Finally, given that front page stories were tied to chiastic reporting, many of the wire stories may have been used as filler for inside pages, and little thought was given to the issue at the time, other than it dealt with a local interest.

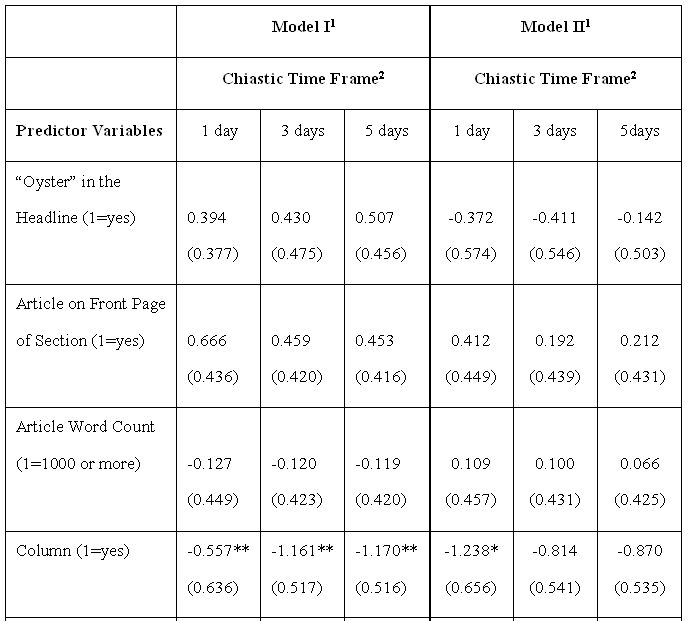

9.7 We report results from logistic regression analyses in Table 3. To avoid undue repetition, the time frames for the regression analyses are presented only for one, three, and five days. Our dependent variable is the number of incidences of chiastic presentations within a specified time period. We present the results for our model variables in the three left-hand columns. We control for the effects of the negative or positive valence of articles in the three right-hand columns of the table.

| Table 3. Logistic Regression Coefficients (and Standard Errors) for the Effects of Predictor Variables on Chiastic Reporting within Selected Numbers of Days. |

|

9.8 Although our zero-order analysis (Table 2) reveals three variables with substantial differences in the percent of chiastic presentations, our logistic regression analyses identify two variables that significantly affect the log odds of chiasmus - column and wire service. As indicated in our zero-order comparisons, each of these predictor variables suppresses chiastic reporting. Earlier we argued that the editorial practices at newspapers could either increase or decrease the likelihood of chiastic presentations. Our finding of a strong negative relation between columns and chiastic presentations would be consistent with the argument that columns reflect high levels of editorial awareness of issues and hence tend to stimulate efforts to maintain editorial consistency. Similar to our predictions about the effects of columns, we were unsure of how wire service articles would affect the extent of chiastic reporting. Our finding that wire service articles significantly reduces the odds of chiastic occurrences provides some support for our speculation that wire service stories may increase local editorial awareness of issues which translate into more consistent publishing, though, to reiterate, other factors play into deciding which wire service stories to use. It could possibly be an outcome of the ways in which columns are developed and contracted with the newspaper, as well as editors thinking about the need to protect the financial interests of the newspaper. These conclusions would benefit with information from the individuals involved in the news making process, but are consistent with previous research (e.g.,Binder 1993).

9.9 Our argument that headlines would be related to consistent presentations is not supported by our findings. This might be a consequence of the division of labor within the newsmaking process which separates headline writing from reporting. Headlines, though, are still under the guidance of editors, and if we are to make the argument that columns and wire service articles are chosen on the basis of presenting a consistent editorial approach, then we need to make the same argument for headlines. However, the effects of headlines differ from columns or wire service articles in the sense that headlines are written to be sensational, and may be inconsistent with the content of the articles. In other words, editors want headlines that demand attention, while the content of columns and wire service articles may generally reflect a more balanced editorial position.

9.10 When we hold the positive/negative direction of stories constant (right side of Table 3), the strength of the effects of columns drops noticeably. On the other hand, wire service articles continue to significantly reduce the odds of chiastic presentations. Controlling for the negative presentation of articles strengthened the support for our suspicion that chiastic presentations may reflect a dialog that is otherwise not apparent.

What the reader is reading

10.1 Given the finding that more than 30 percent of all negative articles were accompanied by positive articles on the same day and over half within a two-week period begs the question of how audience members were interpreting these presentations and how, if at all, their behaviors were affected. One could imagine a household in which one person read a story about heavy metals in oysters, and then came home to a meal featuring oyster stuffing that was prepared using a recipe from the same newspaper and oysters bought that day at the local supermarket. In such a situation it is plausible that one or both of the individuals could bring up the story s/he read, challenge the position of the other story, and be ridiculed for such a stance. Such a scenario is not just fantasy. John Gummer, ex-Minister of Agriculture in the UK, took conflicting reports of mad cow disease to task when he fed his daughter a hamburger in 1990, declaring that British beef was safe (BBC News [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/369625.stm]). While one could argue that Gummer had a vested interest in British beef, the same could be said of a native Louisianian who decides to consume oysters after reading conflicting reports about them.10.2 Another scenario, taken from Gans (1979), would have us thinking from the standpoint of the news organization. In this situation, the organization understands the importance of oysters to its readers and the local economy and culture. Knowing this, conflicting reports are not seen as problematic, but as an opportunity to present various aspects of this important issue. While the stories may cause confusion among readers - should I or should I not eat oysters - the reporting does not, as the local paper should contain any information which is pertinent with regards to oysters.

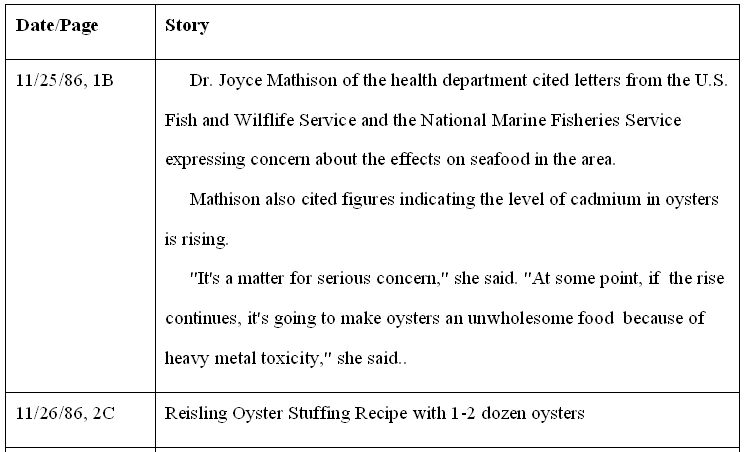

10.3 We do not have public opinion survey results to test for the cultural significance versus safety associated with the oyster to gauge these concerns. Instead, we offer some examples of the type of reporting that was available at this time as a way to give a flavor of the coverage that was being presented. As Gans (1993) argued, the people most likely to be affected by the media are media scholars, yet there is something to be said about reading conflicting information about a topic, especially when it involves a risk situation such as foodborne pathogens and toxins. Here are a few examples from the coverage.

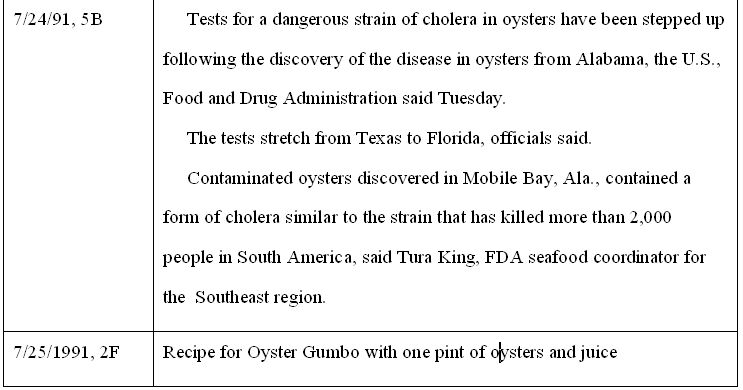

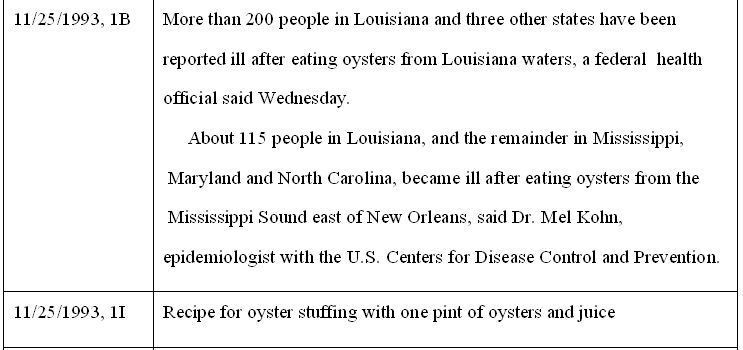

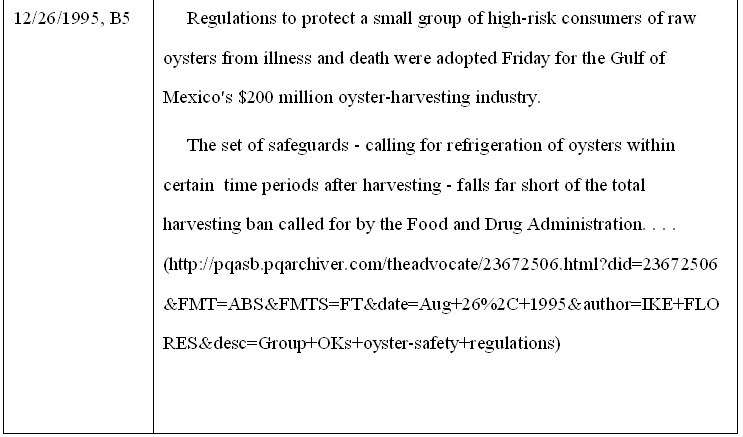

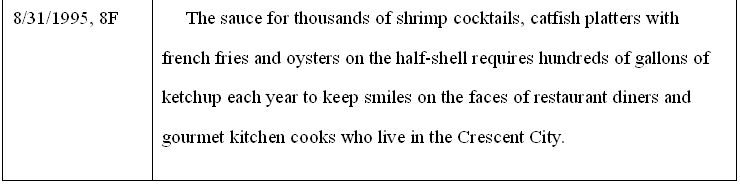

| Table 4. Examples of Chiastic Coverage |

|

10.4 In each case, except for the first, there were discussions of serious illness and death from acute symptoms related to eating contaminated oysters. Cadmium, on the other hand, is considered a carcinogen, so concerns would be tied to long-term problems. In all cases, the problem with consuming oysters is not insignificant, yet we find information which called for eating oysters -- sometimes raw and other times cooked - within a few days of these negative stories and there is no mention of the previous warning. It is important to understand that we do not consider studying the risks of eating oysters and the use of ketchup (last two stories in Table 4) to be equal in its prominence or importance to The Advocate or its readers, but that the fact that these two stories are in close proximity with no explanation for the conflicting reports does call into question how readers would interpret these stories.

10.5 It is difficult to ascertain at this point the effect these various slants on the oyster would have on harvesters, processors, regulators, journalists, consumers and others in the food chains within Louisiana. Dockside oyster sales did not drop significantly over this time period, though price per sack was much more volatile. Agger (1992) has argued that studies of cultural texts should take into account the political/economic interests of those involved. It may be that while The Advocate is concerned with oysters as these mollusks are tied to the financial prosperity of advertisers, the negative stories have helped downstream processors secure lower costs. Economic advantages of news can have impacts beyond the news organization and its advertisers.

Conclusions

11.1 News organizations, like most successful businesses, operate in ways that will make them economically viable. This includes promoting local stories with ties to (potential) advertisers to secure, or at least not threaten, advertising revenues. On the other hand, readers expect news organizations to provide information on issues that may be a threat to their own personal safety. When these two aspects of a local situation collide, news organizations must find ways to deal with the contradiction. This study of one local newspaper in Southern Louisiana found chiastic coverage to characterize the oyster - an economically and culturally important commodity in Louisiana, as well as a potential health threat if consumed under certain circumstances. Findings indicate that editorial processes played into some of this chiasmus. It is also important to understand how this kind of coverage is interpreted by consumers, which plays into Gamson's (1992) work on lay discussions of politics and issues. It would also be interesting to study if they thought in terms of the political-economy of the newspaper and local culture. Whether or not they do think in these terms, the linkage between them may be difficult to separate (Fiske 1992;Hoijer 1992).11.2 This study, then, is at the crossroads of the economics and cultural authority of a news organization and the interpretive abilities of consumers, and much more needs to be done in this area. We have studied what we consider to be the outcomes of conflict within a central node within a network - a node which is expected to be powerful (e.g.,Padgett and Ansell 1993). That this node is a public arena that is expected to be an authority on issues adds additional relevance to its study. What this study does not show is the internal dynamics of those involved in managing the conflicting reports and the interpretive processes of consumers, as well as the gaps between these groups. Studies of such dynamics have shed light on the development of stories and the importance of objectivity (e.g.,Gitlin 1980;Ten Eyck 1999), as well as the ways in which sources are chosen (e.g.,Lee and Solomon 1990;Gans 1979), but have relatively little to say about conflicting information which appears in unrelated stories. The economics and cultural concerns which play into these mechanisms which lead to chiastic reports must take center stage in future research.

Notes

1. For those who have spent any time in Southern Louisiana (both authors were located at Louisiana State University), it is without question that the oyster is an important part of the local food culture. Many cookbooks (e.g.,Stewart 1999; http://www.pepperjam.com/HistoryofCajunandCreole.htm) and historians of that area have pointed this out (e.g.,Hallowell 2001; http://www.cs.wisc.edu/~jmeaux/cajun.html). See also the famous Acme Oyster Bar's web site ( http://www.acmeoyster.com/)2. Our distinction between reporters as experts and news organizations as authorities is not arbitrary. The former term denotes a level of knowledge about a topic, while the latter denotes a level of power. While some may argue that certain reporters are powerful (e.g., anchorpersons for the major television networks), their power is tied directly to their role within the news organization.

3. According to figures from the National Marine Fisheries Service, nearly 65,000,000 lbs. of oysters were sold at dockside between 1986 and 1995, generating nearly $150,000,000. If we were to add in the value-added costs for processing and preparing these oysters for sale to consumers, the value would at least triple.

4. We selected a ten-year period of reporting to provide a sufficient number of cases for our analysis. The 1986 to 1995 period encompassed a critical time for the Louisiana oyster industry during which a ban was proposed on oyster harvesting in the Gulf.

51. We understand that not every individual reader or reporter is cognizant of all the news being carried during specified time periods. However, our concern is not with individual cognitions but with the larger distribution of media presentations.

Acknowledgements

Support for the research reported here was provided by the Louisiana State University Sea Grant College Program and the Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station as a contribution to Southern Regional Project S259. A version of this was paper presented at the Rural Sociological Society Annual Meeting in Portland, Oregon, August 1998.References

ADER, Christine R. 1995. "A Longitudinal Study of Agenda Setting for the Issue of Environmental Pollution." Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 72:300-311.AGGER, Ben. 1992. Cultural Studies as Critical Theory. Washington, DC: Falmer

BAGDIKIAN, Ben H. 1992. The Media Monopoly (4th ed). Boston: Beacon Press.

BAUM, Matthew W. 2003. Soft News Goes to War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

BELASCO, Warren J. 1993. Appetite for Change. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

BINDER, Amy. 1993. "Constructing Racial Rhetoric: Media Depictions of Harm in Heavy Metal and Rap Music." American Sociological Review 58:753-767.

CHAUDHARY, Anju G. 1980. "Press Portrayals of Black Officials." Journalism Quarterly 57:636-641.

CHEW, Fiona and Sushma Palmer. 1994. "Interest, the Knowledge Gap, and Television Programming." Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 24:271-287.

THE CONCISE OXFORD Dictionary of Literary Terms. 1996. (Baldick, Chris, Editor) Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

CRELINSTEN, Ronald D. 1989. "Images of Terrorism in the Media: 1966-1985." Terrorism 12:167-198.

DAVIS, Aeron. 2003. "Whither Mass Media and Power? Evidence for a critical elite theory." Media, Culture and Society 25:669-690.

ERICSON, Richard V., Patricia M. Baranek, and Janet B.L. Chan. 1989. Negotiating Control. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

FISKE, John. 1992. "Audiencing: A Cultural Studies Approach to Watching Television." Poetics 21:345-359.

FRANKLIN, Bob and David Murphy (eds.). 1998. Making the Local News. New York: Routledge.

GAMSON, William A. 1992. Talking Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

GANS, Herbert J. 1979. Deciding What's News. New York: Vintage.

GANS, Herbert J. 1993. "Reopening the Black Box: Toward a Limited Effects Theory." Journal of Communication 43:29-35.Gronow, Jukka. 1997. The Sociology of Taste. New York: Routledge.

GARFINKEL, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

GITLIN, Todd. 1980. The Whole World is Watching. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

HALLOWELL, Christopher. 2001. Holding Back the Sea. New York: HarperCollins.

HILGARTNER, Stephen and Charles L. Bosk. 1988. "The Rise and Fall of Social Problems: A Public Arenas Model." American Journal of Sociology 94:53-78.

HILGARTNER, Stephen and Dorothy Nelkin. 1987. "Communication Controversies over Dietary Risks." Science, Technology, and Human Values 12:41-47.

HOIJER, Birgitta. 1992. "Reception of Television Narration as a Socio-cognitive Process: A Schema-theoretical Outline." Poetics 21:283-304.

INGLIS, Fred. 1990. Media Theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

KEITHLY, W. R., Jr. and K. J. Roberts. 1988. "The Louisiana Oyster Industry: Economic Status and Expansion Prospects." Journal of Shellfish Research 7:515-525.

LANGE, Jonathan I. 1993. "The Logic of Competing Information Campaigns: Conflict over Old Growth and the Spotted Owl." Communication Monographs 60:237-257.

LEATHER, Andrew. 1998. "Economic News in Local Newspapers." Pp. 241-251 in Making the Local News, edited by Bob Franklin and David Murphy. London, UK: Routledge.

LEE, Martin A. and Norman Solomon. 1990. Unreliable Sources. New York: Lyle Stuart.

LUEBKE, Barbara F. 1989. "Out of Focus: Images of women and men in newspaper photographs." Sex Roles 20:121-133.

MCKINNEY, Joan. 1994. "FDA Committed to Seven Month Ban on Gulf Oysters." The Advocate, Baton Rouge, LA, August 3.

MURPHY, David. 1976. The Silent Watchdog. London, UK: Constable.

ORLOVE, Benjamin and Ella Schmidt. 1995. "Swallowing their Pride: Indigenous and Industrial been in Peru and Bolivia." Theory and Society 24:271-298.

PADGETT, John F. and Christopher K. Ansell. 1993. "Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400-1434. American Journal of Sociology 98:1259-1319.

PALETZ, David L, Jonathan Y. Short, Helen Baker, Barbara Cookman-Campbell, Richard J. Cooper, and Rochelle M. Oeslander. 1980. "Polls in the Media: Content, Credibility and Consequences." Public Opinion Quarterly 44:495-513.

PARENTI, Michael. 1993. Inventing Reality. New York: St. Martin's Press.

PELTO, Gretel H. 1987. "Social Class and Diet in Contemporary Mexico." Pp. 517-540 in Food and Evolution edited by Marvin Harris and Eric B. Ross. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

PETERSON, Richard A. and Roger Kern. 1996. "Changing Highbrow Taste: From Snob to Omnivore." American Sociological Review 61: 900-907.

PFUND, Nancy and Laura Hofstadter. 1981. "Biomedical Innovation and the Press." Journal of Communication 31:138-154.

POWELL, Douglas and William Leiss. 1997. Mad Cows and Mother's Milk. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press.

PRICE, Monroe E. 2002. Media and Sovereignty. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

SALWEN, Michael B. 1988. "Effects of Accumulation of Coverage on Issue Salience in Agenda Setting." Journalism Quarterly 65:100-106, 130.

SANDMAN, Peter M. 1993. Responding to Community Outrage. Fairfax, VA: American Industrial Hygiene Association.

Spector, Malcolm and John I. Kituse. 1977. Constructing Social Problems. Menlo Park, CA: Cummings.

STEMPEL, Guido H. III. 1989. "Content Analysis." Pp. 124-136 in Research Methods in Mass Communication (2nd ed.), edited by Guido H. Stempel III and Bruce H. Westley. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

STEWART, Richard. 1999. Gumbo Shop. New Orleans, LA: The Gumbo Shop.

TEN EYCK, Toby A. 1999. "Shaping a Food Safety Debate: Control Efforts of Reporters and Sources in the Food Irradiation Controversy." Science Communication 20:426-447.

TEN EYCK, Toby A. 2001. "Does Information Matter? A Research Note on Information Technologies and Political Protest." The Social Science Journal 38:147-160.

TEN EYCK, Toby A. and Forrest A. Deseran. 2001. "In the Words of Experts: The Interpretive Process of the Food Irradiation Debate." International Journal of Food Science and Technology 36:821-831.

TEN EYCK, Toby A., Paul B. Thompson, and Susanna H. Priest. 2001. "Biotechnology in the United States: Mad or moral science?" Pp. 307-318 in Biotechnology 1996-2000, edited by George Gaskell and Martin W. Bauer. London, UK: Science Museum.

THOMPSON, John B. 1990 Ideology and Modern Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

TUCHMAN, Gaye. 1978. Making News. New York: The Free Press.

UNGAR, Sheldon. 1992. "The Rise and (Relative) Decline of Global Warming as a Social Problem." Sociological Quarterly 33:483-501.

WILLIAMS, Kevin. 1999. "Dying of Ignorance? Journalists, News Sources and the Media Reporting of HIV/AIDS. Pp 69-85 in Social Policy, the Media, and Misrepresentation, edited by Bob Franklin. London, UK: Routledge.

WINTHROP, Henry. 1972. "On Understanding Newspaper Accounts of Contemporary Social Issues." The Midwest Quarterly 13:271-289.

ZELIZER, Barbie. 1992. Covering the Body. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.