Larry Ray

(2002) 'Crossing Borders? Sociology, Globalization and

Immobility'

Sociological Research Online,

vol. 7, no. 3,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/7/3/ray.html>

To cite articles published in Sociological Research Online, please reference the above information and include paragraph numbers if necessary

Received: 30/9/2002 Accepted: 30/9/2002 Published: 22/10/2002

Abstract

Abstract Introduction

Introduction Sociology beyond Societies?

Sociology beyond Societies?

Sociology and Globalism

Sociology and Globalism

Fluids and Solids - Markets and

Embedded Capital

Fluids and Solids - Markets and

Embedded Capital

Migrants, Borders and

Racialization of Place

Migrants, Borders and

Racialization of Place

Conclusions: A Sociology of

Immobilities

Conclusions: A Sociology of

Immobilities

Figures

Figures

| Idealized global markets | Embedded local markets |

| Fluids | Solids |

| Weightless | Heavy |

| Finance/service driven | Sunken capital and high exit costs |

| Auction market prices | Customer market prices |

| Spontaneous order | Visible construction of relationships |

| High risk | Personal networks and obligations reduce risk |

| Abstract rules | Situationally specific rules |

| Institutionalized (systemic) trust | Low impersonal trust and high informal regulation |

| Expansion of credit | Credit limited and tied to obligations |

|

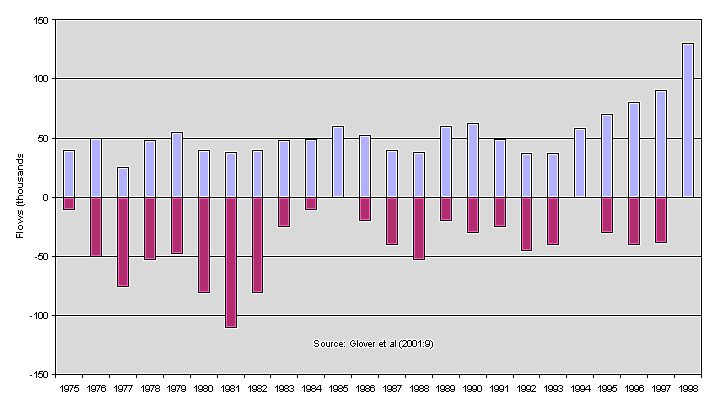

| Figure 2. Net annual flows of international migration 1975-98 |

Notes

Notes2 The polarization of the debate into 'radicals' and 'skeptics' might be useful for teaching purposes, to guide students through a maze of conflicting positions, but it is not particularly illuminating in academic discussion.

3 In particular, critics of the decline of the nation state argument regard this as an obstacle to developing an egalitarian and welfare based socialist strategy of (notably Hirst and Thompson 1996). The hollowing out and the emergence of the regulatory state is not necessarily equivalent to the implosion of nation states that retain crucial and arguably increasing powers over the management of space and mobility.

4 It is worth mentioning too that many mid-century theories explicitly did not equate the social with national societies, notably symbolic interactionism, in which larger structures and entities are secondary to the dynamics of situated interactions. Likewise the earlier Chicago tradition, including people like Thomas and Znaniecki developed nuanced and multi- dimensional concepts of the social.

5Language and culture embody a stock of knowledge - the stored interpretative work of preceding generations - that renders every new situation familiar, in that understanding takes place against the background of culturally ingrained pre-understandings. This 'pre- reflective background consensus' can become an object of reflection only piecemeal, because we cannot suspend judgement on everything at once (Habermas, 1984:123).

6The main centres were Bradford (April and July), Burnley (June) and Oldham (May). There were a total of 1500 violent disorders, 476 people injured and around £10 million worth of damage done (Home Office 2002).

7This is includes fines, possible imprisonment and confiscation of carriers' vehicles, which increases the risks and potential costs of trafficking and makes traffickers increasingly ruthless.

BAUMAN Z (1992) 'Communism: A Postmortem' in Intimations of Postmodernity London: Routledge pp. 156-76.

BAUMAN, Z (1998) Globalization: the human consequences Cambridge: Polity.

BECK, U (1995) Ecological Politics in the Age of Risk Cambridge: Polity.

BLOCH, A. (1999) 'Carrying out a Survey of Refugees: Some methodological considerations and guidelines', Journal of Refugee Studies, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.367- 383.

BOURDIEU P. And WACQUANT L (1999) 'On the cunning of imperialist reason' Theory Culture and Society 16, 1:41-58.

CASTELLS, M (1998) End of the Millennium Oxford: Blackwell.

COMTE, A. (1976) The Foundation of Sociology ed. K. Thompson, London: Nelson.

CROW, G. (2002) Social Solidarities: Theories, identities and social change Buckingham: Open University Press.

DONNAN, H and WILSON T M (1999) Borders: Frontiers of Identity, Nation and State, Oxford Berg.

DURKHEIM, E. (1933) Division of Labour in Society London: Collier Macmillan.

DURKHEIM, E. (1969) 'Individualism and the Intellectuals' Political Studies, 17:14-30.

EBRD, (1995) Transition Report London: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

FULCHER, J (2000) 'Globalization, the nation-state and global society' Sociological Review 48, 4:522-43.

GIBNEY, M. J Outside the Protection of the Law: The Situation of Irregular Migrants in Europe Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper No. 6. At: <http://www.qeh.ox.ac.uk/rsp/indexrsp.html>

GIDDENS, A (1999) Runaway world: how globalization is reshaping our lives London: Profile.

GLOVER S., GOTT, C, LOIZILLON, A., PORTES, J., PRICE, R., SPENCER, S., SRINIVASAN, V & WILLIS, C (2001) Migration: an economic and social analysis RDS Occasional Paper No 67, London: Home Office.

GOFF, P.M (2000) 'Invisible borders: economic liberalism and national identity' International Studies Quarterly 44, 4:533-62.

HABERMAS, J. (1989) The Theory of Communicative Action, Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason, vol 2. Cambridge: Polity.

HANNERZ, U. (1990) 'Cosmopolitans and locals in world culture', in M. Featherstone, (ed) Global Culture

HARVEY, D. (1994) Condition of Postmodernity Oxford: Blackwell.

HELD D, McGREW A, GOLDBLATT D and PERRATON J (1999) Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture Polity.

HIRST P and THOMPSON G., (1996) Globalization in question, the international economy and the possibilities of governance, Cambridge: Polity Press.

HOME OFFICE (2002) Building Cohesive Communities: a report of the Ministerial Group on Public Order and Community Cohesion London: Home Office.

HOMES, S. 'Introduction to "From Postcomunism to Post-September 11"' East European Constitutional Review Winter 2001 pp 78-81.

JESSOP, B. (1992) From the Keynesian Welfare to the Schumpeterian Workfare State Lancaster Regionalism Group: Working Paper no.45.

JESSOP, B (2000) 'The Crisis of the National Spatio-Temporal Fix and the Ecological Dominance of Globalizing Capitalism', International Journal of Uran and Regional Studies 24:273-310.

KECK, M.E. and SIKKINK, K. (1998) Activists Beyond Borders Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press.

LLOYD, C (2000) 'Globalization: Beyond the ultra-modernist narrative to a critical realist perspective on geopolitics in the cyber age' International Journal oft Urban and Regional Research 24, 2:258-73.

MAFFESOLI, M. (1996) The time of the tribes, the decline of individualism in mass society, London: Sage.

MARTIN R (1998) 'Central and Easter Europe and the international economy: The mimits to globalization' Europe-Asia Studies 50, 1:7-26.

MARX, K & ENGELS F (1969) Manifesto of the Communist Party Moscow: Progress Publishers.

O'DOWD L. (1998) 'Negotiating State Borders: A New Sociology for a New Europe' Inaugural Lecture, Queen's University Belfast. At: <http://www.qub.ac.uk/ss/ssp/cibr/odowd.htm l>

OHMAE, K. (1994) The borderless world, power and strategy in the interlinked economy, London: HarperCollins.

PAPASTERGIADIS, N. (2000) The Turbulence of Migration Oxford: Polity.

PARSONS, T (1970) The Social System London: Routledge, Kegan Paul.

PETRAS J. and VELTMEYER, H (2001) Globalization Unmasked: Imperialism in the 21st Century, New York: Zed Books.

POPPI C. (1997) 'Wider Horizons With Larger Details: Subjectivity, Ethnicity and Globalization in A. Scott, ed. Limits of Globalization London: Routledge pp. 284-305.

RAY L. J. (1996) Social Theory and the Crisis of State Socialism Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

RAY L. J. (1999) Theorizing Classical Sociology Buckingham: Open University Press.

RAY, L. J and SMITH, D. (2001) 'Racist Offenders and the Politics of "Hate Crime"' Law and Critique 12, 3:203-221.

RIVERA-BATIZ F (1999) 'Undocumented workers in the labor market' Journal of Population Economics 1:p:91-116.

ROBERTSON, R (1992) Globalization, social theory and global culture London: Sage.

SASSEN, S (1998) Globalization and its Discontents New York: New Press.

SASSEN, S (2000) 'Regulating Immigration in a Global Age' Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 570:65-77.

SCHOLTE J.A. (1996) 'Beyond the Buzword - Towards a Critical Theory of Globalization' in E. Kofmann & G. Youngs eds Globalization: theory and practice, London: New York, Pinter, pp 43-57.

URRY, J. (1998) 'Globalisation and Citizenship' (draft) published by the Department of Sociology, Lancaster University at: <http://www.comp.lancaster.ac.u k/sociology/soc009ju.html>

URRY, J (1999) 'Automobility, Car Culture and Weightless Travel: A discussion paper' Lancaster Department of Sociology On-Line papers. At <http://www.comp.lancs.ac/sociology/s oc008ju.html>

URRY, J (2000a) 'Mobile Sociology' British Journal of Sociology 51, 1:185-203.

URRY, J (2000b) Sociology Beyond Societies - mobilities for the twenty-first century London: Routledge.

VELTZ, Pierre (1996) Mondialisation: villes et territoires: l'économie archipel, Paris: Economica.

WATERS M. (1995) Globalization London: Routledge.

WEBER, M. (1968) Economy and Society. Translated and edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. New York: Bedminster Press.

YEUNG H. W. C (1998) 'Capital, state and space: contesting the borderless world' Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 23,3:291-309.