Richard Kiely,

David McCrone, Frank Bechhofer and Robert Stewart

(2000) 'Debatable Land: National and Local Identity in a

Border Town'

Sociological Research

Online, vol. 5, no. 2,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/5/2/kiely.html>

To cite articles published in Sociological Research Online, please reference the above information and include paragraph numbers if necessary

Received: Accepted: 1/8/2000 Published: 6/9/2000

Abstract

Abstract Introduction

Introduction

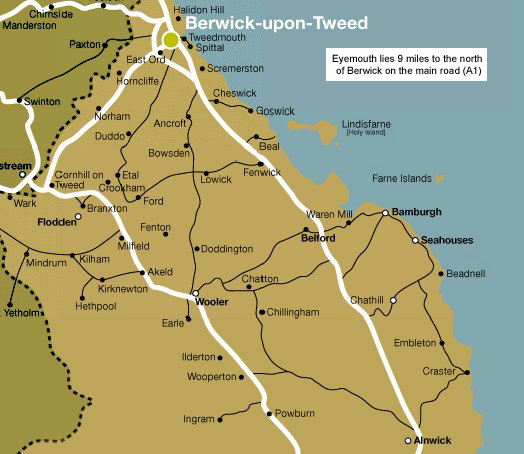

Figure 2: Berwick and the surrounding area

Methods

Methods

Berwick-Upon-Tweed: an ambiguous town

Berwick-Upon-Tweed: an ambiguous town

Mr: I've been inclined to think I was Scottish.

RK: Even though you were born in Berwick?

Mr: Yes, because Berwick was in Scotland originally. So, where do you start a book? You start at the beginning, not in the middle, and everything points towards it being Scottish. The times when the English took over, over the years, all they've done was massacre the town people...It was a bustling port, Berwick was bigger than Edinburgh, you know, it was looked upon as the capital of Scotland, so historically, I think we should belong to Scotland rather than England.

Berwick is Berwick upon Tweed. As I say I feel that it has got its own identity.

It's part of the uniqueness of Berwick, not Scottish, not English, but Berwick.

You get the occasional person says, oh it should be Scottish. You know, the division is the River Tweed, or something like that, and maybe Berwick should be in Scotland, Tweedmouth should be England.

I mean, well not only in the town but a lot of people still regard the river as the border, and certainly when we were on the north side of the river it was always regarded for some reason as being the Scottish side of Berwick, and the south side of the river as the English side.

Interviewer: Do people in Berwick think of themselves as being Northumbrians?

Respondent 1: No I don't think so, I've never classed mysel[f] as that, as far as I'm concerned I'm a Berwicker and that's it like.

Interviewer: Do you know why that is, why there isn't that sense of being Northumbrian?

Respondent 2: Geographical isolation. I mean, we're 30 miles north of Alnwick and that puts us 57 miles north of Morpeth, so we are just Berwick. Berwick has got its own separate identity, always has done and that is a hang-up from the past.

| Always | Usually | Occasionally | Hardly Ever | |

| Berwick-upon-Tweed | 8% | 19% | 35% | 38% |

| Alnwick | 36% | 29% | 19% | 16% |

Berwickers don't consider themselves Borderers at all. The Borderers are considered the Scottish side.

Respondent 1: A lot of things that happen here are Scottish. I mean, it's called a borough which is a Scottish term. All the sports teams, the majority of them played in Scotland over the border....So there is a lot of that. If you went to the town there is something like a 60/40 split in the thing, the town is English but the town has a sort of Scottishness about it for some unknown reason.

Respondent 2: I mean, I'd love to know if someone walking - if someone knew nothing about Berwick, and they walked down the High Street, I don't think they would actually know which it was. I don't think either one comes out, does it? Not, oh this is a Scottish town or oh this is an English town.

The National Identity Question in Berwick-upon-Tweed

The National Identity Question in Berwick-upon-Tweed

| Always | Usually | Occasionally | Hardly Ever | Not Applicable | |

| English | 26% | 20% | 20% | 17% | 17% |

Respondent 1: We (Berwickers) all class wirselves [ourselves] as English 'cos we was born in England.

Respondent 2: I am English 'cos the border is north of Berwick.

Interviewer: Is that why you think of yourself as English?

Respondent 2: Don't know, just think with being born and brought up. It's got a lot to do with your parents as well. I would say just like if your parents are English, you are English.

The older Berwick lot, that's been really born and bred all the time in Berwick, I would say they would claim to be right English.

If they've been born in Berwick, they'll class theirselves as English.

| Extremely | Very | Good | Not very | Not at all | |

| English | 15% | 33% | 45% | 6% | 0% |

| Scottish | 0% | 3% | 18% | 50% | 29% |

| Extremely | Very | Good | Not very | Not at all | |

| English | 3% | 24% | 30% | 30% | 12% |

| Scottish | 12% | 35% | 21% | 26% | 6% |

Interviewer: Would you see Berwick as being an English town?

Respondent: I've always associated Berwick as being Scottish. Despite the fact that it isn't, I've always associated Berwick as being the gateway to Scotland.

Interviewer: Do you know why it has that sort of feeling?

Respondent: Well it's again just probably the dialect. The locals have got that little, the beginnings of a Scottish accent.

Interviewer: Would you think of them as being Scottish, people living in Berwick?

Respondent: Aye I would. I would think of them as being Scottish. Yea.

Interviewer: So you wouldn't tend to think of them as being fellow Northumbrians or English?

Respondent: No I wouldn't, I wouldn't class them as being Northumbrians. I would always class Berwick as being Scottish.

Respondent: I travel south, go to watch England, they class us as Scottish, our accent as Scottish. And you quite surprise them when we tell them that we're still in England. I get that quite a lot, people asking, how come you are coming to watch England when you've got a Scottish accent? But I don't, I don't think I've got a Scottish accent. But to them it must.

Interviewer: How do you respond to that when they say that you're Scottish?

Respondent: Well just try and explain to them that we are English, I was actually born in England and Berwick is in England but it's not easy.

It's amazing the number of people, especially the further south you go, whether it's wi' seeing, I don't know, Berwick maybe playing in the Scottish league. They think we are Scottish.

The folk in the town which weren't born in Castlehills call the ones which were 'Scotchies' because there is still a hell of a lot of folk in the town even, [who] count the Berwick side as being in Scotland and the Tweedmouth side as being in England.

| Always | Usually | Occasionally | Hardly Ever | Not Applicable | |

| Scottish | 15% | 2% | 11% | 13% | 59% |

People from Newcastle might think I've got a Scottish accent and things like that so, for that reason, with me living so close I do like to associate myself with Scotland because of that.

[accent/dialect; geographical proximity]

Although I'm sort of born in Berwick which is in England, on my birth certificate, I prefer to think myself as Scottish. And because the border is so close you seem to have an affinity with Scotland, because you are that close, you know, 'Oh, what the hell is 3 mile, I'm Scottish anyway'.

[denies birth marker; emphasises geographical proximity to Scotland, hence 'affinity']

Interviewer: Would there be many people born and bred in Berwick who would actually claim to be Scottish?

Respondent 1: Your two brothers.

Respondent 2: I've got two brothers who were born in the maternity home just at this side of the river.

Interviewer: Castlehills?

Respondent 2:Yea, so yea they take that, they're Scottish, they're over the right side of the Tweed as they say.

[north of the Tweed as birth marker and place of residence]

Interviewer: So, in terms of your nationality, you would describe yourself as being Scottish?

Respondent: Ahha.

Interviewer: Do people say to you, 'oh come on you were born in Berwick', do you get that sort of thing?

Respondent: No I think it's just part and parcel of Berwick.

[location and history of Berwick-upon-Tweed]

Respondent: I would say Scottish.

Interviewer:.Can I ask why?

Respondent: I just think I would prefer, I think we would be better off being in Scotland. Because in England Berwick is so far north that we are forgotten about.

Interviewer: Would this be quite common in Berwick, that people, even like yourselves born and bred in Berwick would say they were Scottish?

Respondent: I think there would be at least 50% would say they are Scotch! [sense of remoteness from centres of power in England]

Respondent: I say, if you cut my arm there would be Scottish blood there.

Interviewer: So you refer to your ancestry?

Respondent: Yes 'cos it's your parents, isn't it.

I'm English because Berwick is part of England, this is where I was born, and to me it would be as ridiculous to say I was Scottish as somebody from Eyemouth who said they was English. Because it isn't an actual fact.

Respondent 1: I used to say British quite a lot when I was having arguments.

Interviewer: That would settle the arguments?

Respondent 1: Aye, you know, I would just say, oh well we're all British, it doesn't make any difference.

Interviewer: You say it's a difficult question for you to answer, am I Scottish or am I English. If I asked you what your nationality was, what would you say?

Respondent 2: I'd have to say British.

Interviewer: Can I ask you why you would describe yourself as British?

Respondent 2: Because I don't feel Scottish or English!

Interviewer: So it is just almost a way of by-passing the question?

Respondent 2: Well that's it.

'Just Berwickers'

'Just Berwickers'

Interviewer: If I was to ask your nationality?

Respondent: Well, Berwicker, sort of really in between, I can't say.

I'm a Berwicker, never sort of 'I'm English, I'm Scots'.

Just being in the toon all my life like, you're neither Scotch nor English, so you're a Berwicker.

Respondent: Most people like I say, you are in-betweenies. Like the language is like half Scottish, half Geordie, so you are more in-between.

Interviewer: But if pushed?

Respondent: Me personally, I'd sway to England. More for sporting reasons and what have you.

Interviewer: Do you think that would be the most common view that if pushed people would say English?

Respondent: They would just say, I'm a Berwicker.

They're Berwickers, they're nothing else but Berwickers, they don't associate themselves either with England or Scotland.

I've heard that said at work, on quite a few occasions people have said, 'oh I'm not English or Scottish, I'm from Berwick'.

There is still quite a strong tendency not to get caught up in the nationalist thing, It's probably outsiders coming in that tend to try and put them in one camp or the other. And I think they do regard themselves as being Berwickers and they are neither Scottish nor English. They are slap bang on the border and I suppose they can't afford to be either really.

Most of the people who are real genuine Berwickers, they are different. I can see that now, they're not Scots or English and I like that really 'cos I was always confused over this. I think that they don't give a fiddle for anyone really, they're Berwickers and Berwick is their home and they don't think much of that lot and they don't think much of that lot. But Berwickers are alright.

When you work with a lot of people from Scotland and you say you're Berwickers they say, don't talk silly, you're English. They won't have it like.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Notes

Notes2We began a major programme of research in late-1999 until 2004, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, entitled 'Constitutional change and identity'. Essential elements of this include an examination of how English people in Scotland and Scots in England negotiate identities in the new national communities.

3Examples of these include : 'Berwick people not English' Scotsman 17/5/1967 and 'A town on the border between war and peace' Herald 30/3/96

4 In interviews with a number Scots living in nearby Eyemouth, a Scottish town located 6 miles north of the border many did indeed claim that living close to the border gave them a heightened sense of national identity.

5We discuss identity markers and rules in Bechhofer, et al, 1999, 'Constructing national identity: arts and landed elites in Scotland' Sociology, Volume 33 No.3.

6We carried out a number of interviews in the town of Alnwick (25) and the villages of Norham (5) and Horncliffe (5).

7Berwicker was a term commonly used in the town and surrounding communities to describe people who considered themselves, or were considered to be, locals of Berwick-Upon-Tweed. In the course of our interviews in the town, we asked respondents using our identity measures, 'What makes someone a Berwicker'? Respondents had no difficulty in understanding this question and 84% saw being born in Berwick as 'Extremely or very important' in making someone a Berwicker, 67% saw having parents born in Berwick as 'Extremely or very important' and 58% saw parents being resident in Berwick as 'Extremely or very important'. These views did appear to translate into identity claims. Of our 116 respondents in Berwick-upon-Tweed, 52 (45%) had been born there, whilst slightly more people in our sample 54 (47%) claimed to be Berwickers. 40 (77%) of those born in the town claimed to be Berwickers. The remaining were in the main people with lengthy residence in the town, a good number with ancestral/family links to it. When it came to local identity at least, it appeared that Berwickers were prepared to play by the prevailing identity rules.

8We would like to acknowledge the help of the staff of the University of Edinburgh Data Library, in particular, Donald Morse, Alistair Towers, Robin Rice and Joan Fairgrieve.

9A referee raised the possibility that within interviews such as these an interviewer effect might operate, and this is an important methodological issue. Because the same person, a Scot, did all the interviews we have no empirical control and the possibility of an interviewer effect exists. We do not wish to deny that in studies in some areas, and under some circumstances it is likely that class and (especially) gender effects do operate. It is then a matter of judgement whether there was a 'nationality effect' of any significance and we are inclined to think not. The interviewer, coming as he does from the Scottish western Borders does not have a strong Scottish accent and no respondent made any reference, favourable or otherwise to it. He has a several years of experience of conducting interviews on national identity. He is skilled at avoiding any kind of behaviour which might be interpreted as threatening, and crucially was very careful to be nationally neutral in the way questions were phrased and comments by respondents were received. It does seem a priori unlikely that people would have responded so consistently if an interviewer effect was operating as one would anticipate that people would respond differently to the interviewer's Scottish nationality. Until some other researchers (perhaps with different accents) replicate our work in a very similar context, we cannot with any certainty go further.

10A computer package designed to aid analysis of qualitative data by an Edinburgh colleague, Ian Dey.

11Many respondents in Berwick-upon-Tweed were able to provide unambiguous accounts of their national identity as either English or Scottish. A considerable proportion of these were 'incomers' to the town from different parts of England and Scotland, but for some Berwickers holding an English national identity was less problematic. They mobilised place of birth, residence, upbringing, and ancestry in ways familiar to us from our earlier studies. In this paper however, we foreground those inhabitants of the town who chose to mobilise other identity markers and different identity rules as a result of the identity context Berwick-upon-Tweed provided.

12Here the emphasis is upon that part of Berwick-upon-Tweed north of the river Tweed ('Berwick'), as opposed to Tweedmouth or Spittal south of the river.

13The identities offered in this identity measure were Berwicker, Northumbrian, Borderer, English, Scottish, British and European.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

HARRIS R. (1972) Prejudice and Tolerance in Ulster, Manchester : Manchester University Press.

JUDAH, T. (1997) The Serbs : history, myth and the destruction of Yugoslavia, New Haven: Yale University Press.

MCCRONE, D., BECHHOFER, F., KIELY, R. and STEWART, R. (1998) 'Who are we?: Problematising national identity', The Sociological Review Vol.46, No.4, pp 629-652

MODOOD, T. (1998) Ethnic Minorities: diversity and disadvantages, London: Policy Studies Institute.

MALCOLM, D. (1994) Bosnia: a short history, London: Macmillan.

O'DOWD, L and WILSON, T. (1996) (Eds.) Borders, Nations and States : frontiers of sovereignty in the new Europe, Aldershot: Avebury.