Social Theory or Attitudinal Types: A Case Study of Attitudes Towards Relationships

by Laura Watt and Mark Elliot

University of Manchester; University of Manchester

Sociological Research Online, 19 (1) 13

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/19/1/13.html>

10.5153/sro.3314

Received: 3 Dec 2013 Accepted: 17 Jan 2014 Published: 28 Feb 2014

Abstract

Sociological theories can be viewed as models of (sub)-populations. In this paper we explore the possibility of representing social theories as attitudinal types rather than as descriptions of society at large. To test this idea we investigate the relevance of four different theories of couple relationships to the attitudes of 18 to 30 year olds. Rather than testing these theories via aggregate social trends, we investigate the plausibility of treating the four social theories as attitudinal types that can be used to distinguish between the thoughts and feelings of different young adults. A self-completion attitude measure is created and used to gather data from a sample of 18 to 30 year olds living in Preston, UK (n=306). Cluster analysis is then used to identify potential attitude types from among the respondents which are discussed in relation to the four theories.

Keywords: Relationships, Attitudes, Couples, Intimacy, Individualisation, Confluent Love

Introduction

1.1 This paper explores the possibility of representing social theories as attitudinal types. To do so it explores four different theories of couple relationships[1] within the attitudes of 18 to 30 year olds living in Britain. These theories are: two theories of individualisation (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995; Giddens 1992), a theory of exchange (Rusbult 1980) and a theory of romantic love (Giddens 1992; Jackson 1993). The four theories each offer a different account of how coupling operates in Western society: how those relationships are formed, maintained and possibly dissolved. In particular, the theories of individualisation are sociological theories of change that describe how coupling is transforming as society moves from a traditional to a post-traditional state. Rusbult's (1980) exchange theory is a psychological theory, providing a set of principles that supposedly govern Western coupling. Finally, the theory of romantic love offers a traditional[2] account of couple relationships centred upon the practice of life-long marriage which can therefore be viewed as antithetical to individualisation or detraditionalisation theory.1.2 Each of these theories contains a set of propositions describing what their authors suppose are universal or emerging tendencies in a given (typically western) population. However, rather than testing the validity of each proposition (or tendency) via aggregate social trends, we test each theory as a complete 'type' or set of propositions. Indeed, the propositions contained in each theory are theoretically related to one another. We test the inter-relation of the propositions contained in each theory by exploring whether, if an individual adheres to proposition z of a given theory, he or she also adheres to propositions x of that theory. Thus we are less interested in whether the theories accurately describe universal or even highly prevalent tendencies, but whether in toto each theory works as a description of how an individual might plausibly think, feel and behave.

1.3 In order to test the theories in this way we explore whether or not they can be used as attitudinal classes that distinguish between the attitudes of different 18 to 30 year olds living in Britain. We focus upon this young adult population because two of the theories being tested are theories of social change (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995; Giddens 1992). Whilst one might question the merit of testing the relevance of these particular theories via cross-sectional data, these theories are twenty years old and if we are not to regard them as mere futuristic speculations then evidence for them should be found in the relationship attitudes of current adults and specifically of the newest cohorts.

1.4 To fulfil our research aim, we create an attitude measure designed to test the extent to which a respondent's attitudes are consistent with each of the four theories. We then use the newly created measure in a study devised as an initial exploration into the feasibility of treating the four theories as attitude types. Data are collected from a sample of 18 to 30 year olds living in Preston, UK (n=306). Cluster analysis is then used to explore patterns in the data in order to identify potential attitude types amongst these young adults and investigate the extent to which the four theories are mirrored in these types.

Theories of Couple Relationships

2.1 There is a wide body of social theory regarding family and personal relationships, ranging from the more structuralist accounts of functionalism (see, for example, Murdock 1949 and Bales & Parsons 1956) and Marxism (see, for example, Engels 1884 and Zaretsky 1976) to more recently developed micro accounts. One of the most prominent among the latter is individualisation theory, a theory of social change which suggests relationships in the West are becoming detraditionalised. According to individualisation theorists, through an increased focus upon the self as the governing force in one's life, individuals are becoming less likely to follow traditional relationship trajectories deemed appropriate by external forces, and more likely to construct any type of relationship they would like to satisfy personal preferences. Two prominent theories of individualisation are those offered by Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995) and Giddens (1992).The Normal Chaos of Love (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995)

2.2 Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995) claim that, as Western society moves towards an era of post-modernity, there is a greater focus upon the individual above the collective. With this focus comes the belief that, rather than having to adhere to traditional norms of behaviour (for the good of society at large), one can choose any lifestyle that satisfies personal demands. As a result, whilst most individuals once followed the relationship trajectory of pre-marital courtship, marriage and children, this trajectory is being replaced by a broad spectrum of relationship types designed to fulfil the personal desires of those within them.

2.3 Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995) argue that, as a result of greater autonomy and self-reflexivity in decision making, individuals experience a greater sense of risk in the lifestyle choices they make. Indeed, as the authority of cultural meta-narratives comes into question and individuals are expected to construct their own biographies, they no longer experience the security once provided through the deterministic nature of universal life trajectories, but instead must carry the burden of responsibility for any choices they make.

2.4Added to this picture of uncertainty is one of disappointment; these authors argue that the demands of a modern and highly individualistic world (and specifically the demand for individuals to be mobile agents in a global economy) make it difficult for individuals to sustain the relationships they would actually like to have (namely stable family relationships). Thus, Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995) argue that, while individuals increasingly believe they are free to choose any type of relationship they would like, such choices are limited by contradictory forces. Finally, they argue that this increased sense of disappointment and dissatisfaction tends to mean greater temporariness in relationships that are formed.

The Transformation of Intimacy (Giddens 1992)

2.5 Giddens (1992) argues that, while modern relationships were characterised by romantic love, post-modern couple relationships are characterised by what he terms 'confluent love'. According to Giddens, while romantic love emphasises the importance of finding the right person (based upon a belief in a 'one and only love'), confluent love emphasises the importance of finding the right relationship, one incorporating the right qualities. In his view there is no notion of 'forever' within confluent love, but rather the idea that relationships need to be negotiated and worked at over time if they are to continue. Based upon this premise, there are no universally determined norms of behaviour in relationships based upon confluent love; any type of behaviour is acceptable so long as it is mutually agreed.

2.6 With no ascribed patterns of behaviour, partners are required to be open and honest with one another in terms of what they do and do not want from their relationship while at the same time listening to, and respecting, one another's desires and demands. Emotional intimacy is therefore central to the concept of confluent love. Giddens (1992) uses the concept 'democratisation of the private sphere' to claim that as partners experience higher levels of emotional intimacy by sharing and respecting one another's needs and desires, greater equality occurs between them which, in the case of heterosexual relationships, means greater equality between men and women.

2.7 Finally, Giddens (1992) uses the term 'pure relationship' to depict a relationship based upon confluent love. It describes a relationship entered into for its own sake (for the benefits it offers each partner) rather than one that exists because of external phenomena such as children, a marital contract or social expectation. Giddens (1992) claims that, while other benefits will differ from relationship to relationship, every pure relationship exists because of the confluent love, or emotional intimacy, it provides to those within it. In a pure relationship, if such intimacy ceases to exist, so will the relationship; the notion of unconditional commitment, therefore, has no relevance. Thus, like Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995), this theory assumes post-traditional relationships are potentially more transient than traditional ones.

The Investment Model of Commitment Processes (Rusbult 1980)

2.8 With its focus on the role of individual agency in shaping personal relationships, individualisation theory shares common ground with the economic approach to couple relationships. Applying principles of economics to an understanding of human interaction, this approach argues that individuals are rational agents who construct their relationships in order to maximise personal gain. It therefore assumes that relationships are only entered into and maintained if the rewards of being in that relationship outweigh the costs of being so for each partner. One prominent economic theory of coupling is Rusbult's Investment Model of Commitment Processes (1980) which suggests relationship endurance depends upon three factors: satisfaction levels, quality of alternatives, and investment size.

2.9 Satisfaction levels (positively correlated with relationship endurance), in turn, depend upon two factors. First, a relationship's reward-cost ratio, which is the amount of benefit a partner gains from being in the relationship compared to the costs of being so; the higher the relative rewards, the greater the satisfaction level. Second, the comparison level or standard by which a given relationship is compared. This standard is based upon one's notion of an ideal relationship which might incorporate imagined relationships or memories of previous ones. The comparison level allows for a subjective element in judging a relationship as good or bad; a relationship with a given reward-cost ratio would be judged more favourably by someone with a lower comparison level. Thus, Rusbult (1980) supposes that the greater the reward-cost ratio and the more closely a relationship matches one's comparison level, the greater the satisfaction level and the more likely it is for the relationship to continue.

2.10 Quality of alternatives is negatively correlated with endurance. The concept refers to how desirable one perceives the alternatives to a current relationship to be; these alternatives might include a different relationship which is available to oneself or the possibility of being single again. If one's level of satisfaction in a current relationship (as derived above) is perceived as greater than the expected level of satisfaction for all available alternatives, the current relationship is more likely to continue.

2.11 Finally, investments (positively correlated with endurance) refer to any resource attached to a given relationship that would be lost of that relationship ended. They can include immediate investments such as money spent on dates but also more long-term investments such as time spent with a partner. Rusbult (1980) claims that, even if a relationship appears unsatisfactory and there are desirable alternatives to it, that relationship can persist if high investments have been made into it.

Romantic theory: A traditional account of couple relationships

2.12 Rusbult's (1980) theory, and the economic approach more generally, is criticised for underemphasising the effect that emotion, in particular love, has upon couple relationships (see Turk and Simpson 1971). Several authors (Giddens 1992; Jackson 1993; Burkitt 1997) have discussed the concept of romantic love and the role it plays in partnering. Here, their arguments are drawn together to provide a theory of more traditional coupling to contrast with those of post-traditional coupling presented by the individualisation theorists discussed above. In fact it is Giddens (1992) who offers the fullest account of romantic love, using it as a precursor to his theory of post-traditional coupling and comparing it with the notion of confluent love which he claims is characteristic of the latter.

2.13 Giddens (1992) argues that different types of love dominate British coupling during different eras. He claims that romantic love has been dominant since the late Eighteenth Century and that its defining qualities are representative of this era. He explains that during this time there came a reaction to the extreme rationality of the Enlightenment era, a reaction that gave rise to the Romantic Movement which called for a return to feeling, the emphasis of emotion over reason[3] and the realm of the irrational, inexplicable and therefore uncontrollable. According to Giddens (1992), the idea that romantic love arose during a time when increased rationality was being challenged by a return to feeling is fundamental to the nature of this emotion, which combines both mystical and inexplicable elements with those that promote rational order and control.

2.14 Both Giddens (1992) and Jackson (1993) claim that romantic love is grounded in a belief that love is a mysterious and uncontrollable phenomenon that happens to an individual beyond his or her control. As such, it incorporates the notion of 'love at first sight' through which two people fall in love instantly rather than over time. Giddens (1992) also discusses the concept of a 'one and only love' which assumes everyone has a soul mate or perfect match with whom true love would only be experienced. Through this notion, partners are viewed as two halves of the same whole that, once united, can bring self-completion to each other.

2.15 Through the belief in a one and only love, monogamous, life-long marriage is central to the concept of romantic love. It is in this way that Giddens (1992) claims romantic love, while incorporating mystical and inexplicable ideals, promotes a sense of rational order and control; through their experience of romantic love individuals are able to predict and control their future, by entering a life-long commitment with the person they love. In this way, unlike those based upon confluent love, there is no scope for a 'romantic relationship' to end.

Testing the theories as attitudinal types

3.1 There are disagreements regarding how the term attitude should be defined (see, for example, Albarracin et al. 2005; Ajzen 2005; Bohner & Wanke 2002). In this paper, we define an attitude as any combination of beliefs, feelings or imagined behaviours[4] that are directed towards a given object or class of objects. Our definition therefore assumes that attitudes are purely emotional/cognitive entities that are distinct from actual behaviour. Based upon this definition, the theories just discussed make arguments, not just about how individuals behave in couple relationships, but about their attitudes towards them. For example Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995) argue that individuals enter and dissolve couple relationships with greater frequency (behaviour) because they believe they can create relationships that will satisfy personal desires but feel disappointed with the reality of those relationships (attitudes).3.2 Even if viewed as distinct, one might assume that a person's behaviour is associated with his or her attitudes (especially in the case of imagined behaviour) meaning that measures of one might infer something about the other. However, this assumption has been heavily contested (see Oppenheim 1988; La Pierre 1934) and we make no such assumption here. In fact we leave the question of behaviour entirely to one side, being interested only in how these theories might be relevant to the attitudes of our research population, in particular as a typology of such attitudes. With this focus we do not claim to be testing the theories in their pure form, which would require both behavioural and attitudinal data, but rather aim to investigate whether the theories provide a useful framework in which to interpret any patterns or types of attitudes that might exist.

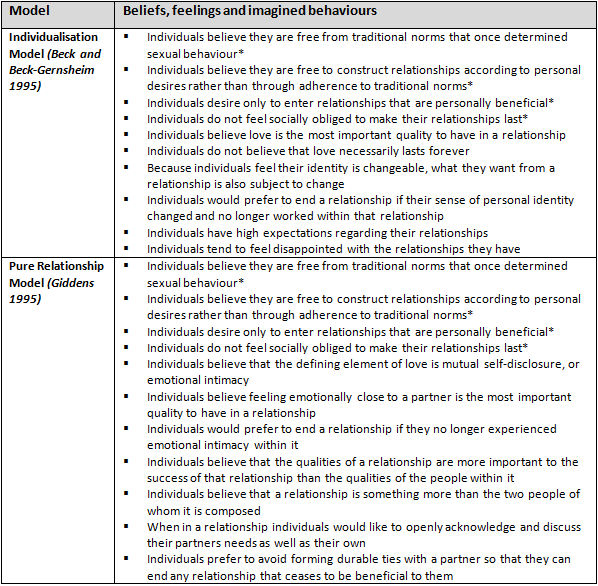

3.3 In order to test whether these theories can be viewed as attitudinal types we treat the arguments they each make about actual behaviour as arguments regarding imagined behaviour: how an individual would plan, expect or prefer to behave in a given situation. Based upon this premise, we present each of the theories as an attitude model, consisting of a unique set of feelings, beliefs and imagined behaviours that an individual would hold if he or she adhered to that model (see Table 1). All of these statements have been drawn from an extensive review of the literature surrounding the theories - see Watt (2013) for more detail. Not all of the propositions are unique to one of the four models; in some cases more than one of the theories make the same argument about couple relationships. For example, as they each stem from individualisation theory, both Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (1995) and Giddens (1992) argue that individuals feel free to construct relationships according to personal desires rather than through adherence to traditional norms. In the table, those propositions that are included in more than one model are marked with an asterisk.

3.4 For ease of reference we entitle the models as follows: The Individualisation Model (derived from Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995), the Pure Relationship Model (derived from Giddens 1992), the Investment Model (derived from Rusbult 1980) and the Romantic Model (derived from Giddens 1992 and Jackson 1993).

| Table 1. Beliefs, feelings and imagined behaviours suggested by each attitude model |

|

A study of 18 to 30 year olds

4.1 To explore the relevance of these attitude models in the 18 to 30 population, we designed a self-completion attitude measure. The measure consists of 40 statements, each of which either supports or refutes one of the propositions listed in Table 1. Respondents were asked to mark their level of agreement to each statement (and therefore their level of agreement to each proposition) along a five point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Where possible, to help ensure their construct validity, the wording of the statements matches the wording contained in the relevant literature. The writing of the statements underwent several stages of re-drafting; the final stage involved a small pilot study where respondents were able to discuss in depth any issues they had responding to the measure.4.2 Once created, the attitude instrument was used to collect data from a sample of 18-30 year olds living in Preston[5] in the UK (n=306). Steps were taken to help make sure this sample was representative of the research population, though at this stage of the research it was not our primary concern. Rather, the aim of our data collection was to begin exploring the feasibility of treating the four social theories as attitude types. A multi-stage cluster and probability sampling method was employed. The first stage of cluster sampling involved the selection of three Super Output Areas within Preston. Based upon their deprivation scores, an SOA which is more than averagely deprived, one which is averagely deprived, and one which is less than averagely deprived, were selected. The demographic structures of the young adult population of each selected SOA were comparable to that of the young adult population of Britain as a whole. The second stage of sampling involved the random selection of streets within each SOA and the third stage, the random selection of households from each street.

4.3 Surveys were sent to 2250 addresses[6], addressed to the first person listed at that address on the electoral register. A covering letter asked if the addressee or someone else living in their household was aged between 18 and 30 and, if so, to complete the questionnaire and leave it for collection on a day specified. Households with more than one 18 to 30 year old living there were asked to arbitrarily select one respondent from amongst them. 306 individuals aged between 18 and 30 completed a questionnaire. As questionnaires were delivered to 2250 addresses, a total survey response rate of 13.6 % was obtained. At many of these addresses, however, there would have been no one in the target age range. Using the Labour Force Survey[7] we estimate that 26.6%[8] of households in our sample contain one or more individuals aged 18 to 30, suggesting a response rate closer to 50%.

4.4Once collected, the questionnaire responses were coded and entered into SPPS. In the first instance, we conducted a Principal Components Analysis on the data to investigate whether any of the single items in the attitude measure, if they were shown to be measuring the same latent construct, could be combined into multi-item attitude scales. Based upon the results of this PCA, two pairs of the 40 single-item measures were combined; these pairs are:

- I would only have sex with someone I was in love with/I would only have sex with someone I was in a relationship with

- I would be less committed to a relationship if I knew I could start a new one with someone else/My relationships are never as good as I expect them to be

Cluster analysis

5.1 We use cluster analysis[10] to investigate the extent to which 18 to 30 year olds can be categorised into different types according to the attitudes they hold towards couple relationships. Cluster analysis groups together cases with the most similar responses into x number of clusters; here the method is therefore used to group together respondents with the most similar attitudes in order to explore whether the differences between these clusters reflect the differences of the four models shown in Table 1.5.2 There are two main methods of cluster analysis; K-means and Hierarchical. Hierarchical is more exploratory in nature, it begins by treating each case as a single cluster and joins together the two cases that are most similar, continuing to do so until all the cases/clusters have been combined into a single cluster. With k-means clustering, one specifies the number of clusters one would like to produce from a data set and it produces the most suitable cluster solution for that specified number.

5.3 K-means offers a more reliable way of producing clusters, providing the optimal cluster solution for x number of clusters. However, the nesting feature of hierarchical clustering (knowing which clusters merge at earlier and later stages of the clustering process) can be a useful way of exploring the data. For this reason we opt for hierarchical clustering (using Ward's method and the squared Euclidean measure of distance as the metric), though we use k-means clustering to cross-validate the results.

5.4 Finding the appropriate number of clusters to 'fit' a data set is an important issue in cluster analysis. There are two things to bear in mind. First, one wants the cases in each cluster to be as similar as possible. Second, one wants the clusters to be as dissimilar as possible. To help ascertain the optimal cluster solution we save the results of the two, three, four, five, six, seven and eight cluster solutions, produced via hierarchical clustering. We stopped at eight clusters with the assumption that any more would be too difficult to interpret. Then, using the procedure detailed in Calinski & Harabasz (1974), we calculate the variance ratio criterion (VRC) for each solution based upon the following equation, to show how much variance in the variables is accounted for by a given cluster solution[11]:

VRCk = (SSB / (k-1)) / (SSW / (n-k))Where:

SSB is the sum of squares (of the Euclidian distances) between the clusters

SSW is the sum of squares (of the Euclidian distances) within the clusters

k is the number of clusters in a given solution

5.5 To use this VRC to ascertain the best cluster solution we then compute the W statistics for each of the solutions using the following equation:

Wk = (VRCk+1 - VRCk) - (VRCk - VRCk-1)

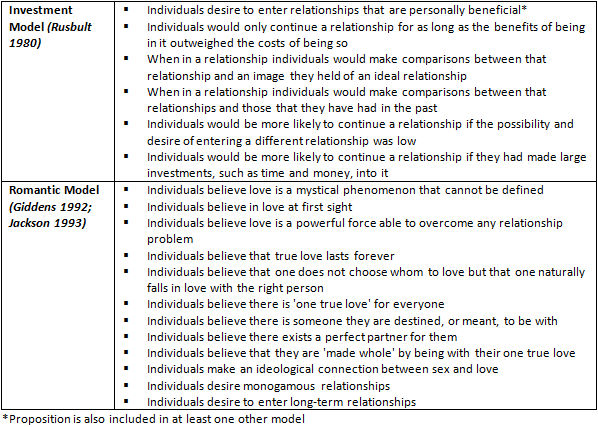

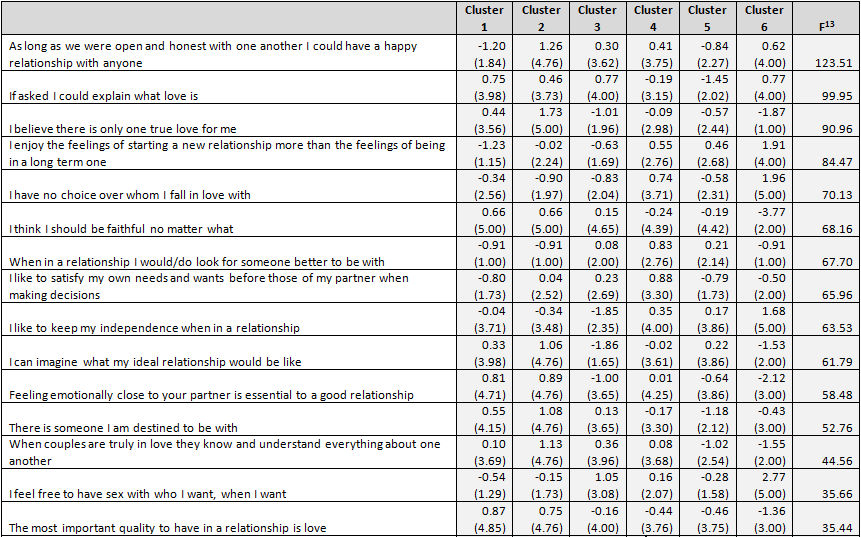

5.6 Following Calinski & Harabasz, the most appropriate cluster solution is that which minimizes the value of W. Table 2 shows the VRC and W statistics for each of the cluster solutions. Owing to the term VRC k-1, the minimum number of clusters that can be selected via this criterion is three, as the maximum number of clusters is eight the W statistic for neither the two cluster or nine cluster solutions are included in the table. The table shows that the six cluster solution has the lowest W suggesting it to be the most useful for understanding variance in these data.

| Table 2. VRC (and w) statistics for two to nine cluster solutions produced via hierarchical clustering (using Ward's method and squared Euclidean measure of distance) |

|

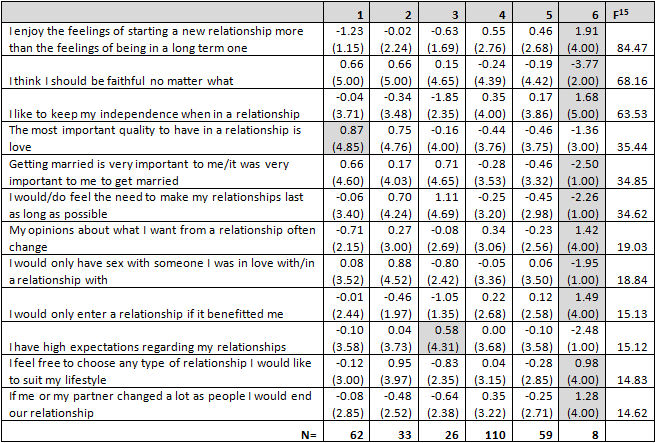

The results

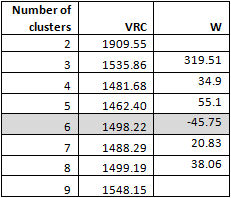

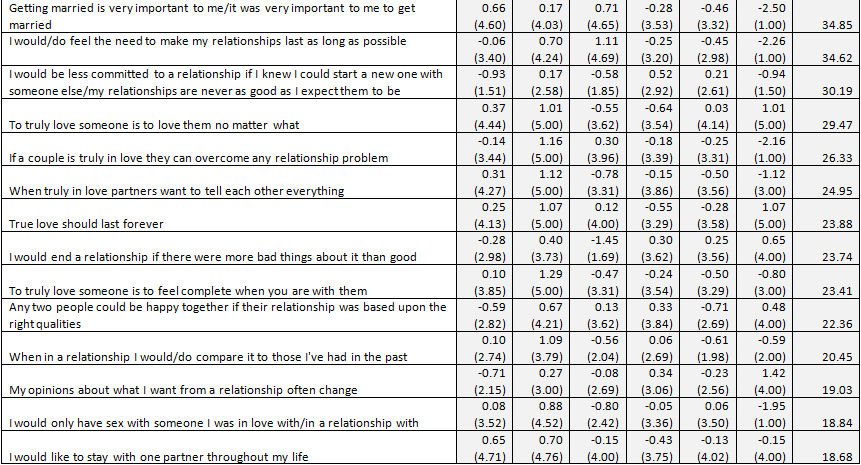

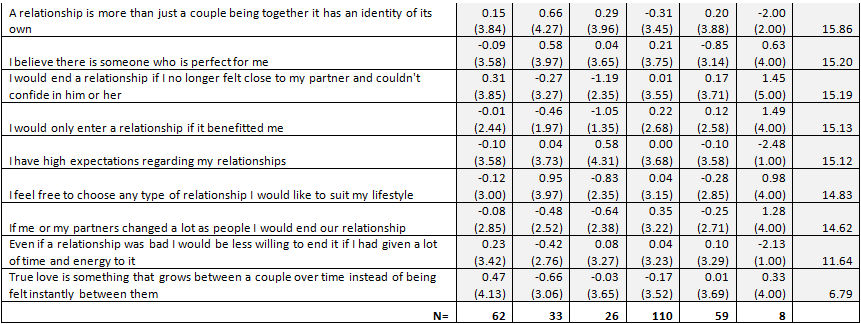

6.1 Based upon the results shown in Table 2, we begin by comparing the mean attitude scores of the six cluster solution. As a check on the robustness of these results we also produce a six cluster k-means solution. The mean scores produced via the hierarchical cluster solution are used as the initial centroids in the k-means clustering. These centroids do not shift at all during the iterations of the k-means clustering meaning the results of both cluster solutions are identical, providing evidence for their stability.6.2 The results of the hierarchical six cluster solution are shown in Table 3. Both the standardised and actual mean scores for each cluster on the 38 attitude items are listed; the standardised scores are listed first with the actual scores in brackets. The actual mean scores range from 1 to 5 based upon the coding 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree. The standardised mean scores show how much the mean score of a cluster deviates from the mean of the whole sample if that mean was zero. The standardised scores are therefore relative; they indicate how much a cluster disagrees or agrees with a statement in relation to the other clusters rather than indicating their absolute level of agreement with a statement. In many cases negative standardised scores can be interpreted as disagreement with a statement while a positive standardised score can be interpreted as agreement with it. However, because these are relative mean scores, this is not always the case; in many cases a negative score merely indicates that a cluster agrees less strongly with a statement than the sample as a whole. As a result it is important to look at both the standardised and actual mean scores.

6.3 Also included in Table 3 are the F statistics for each attitude item. This statistic indicates how large the difference is between the mean scores of each cluster on that particular item; the greater the F statistic the greater the difference. The items are listed in the table according to this statistic; the scale with the largest F statistic and thus for which there is the greatest degree of variability between the clusters is at the top of the table while that with the lowest degree of variability is at the bottom.[12]

| Table 3. Standardised and unstandardised (bracketed) mean scores on attitude items for six clusters produced via hierarchical clustering (applying Ward's method and squared Euclidean measure of distance) |

|

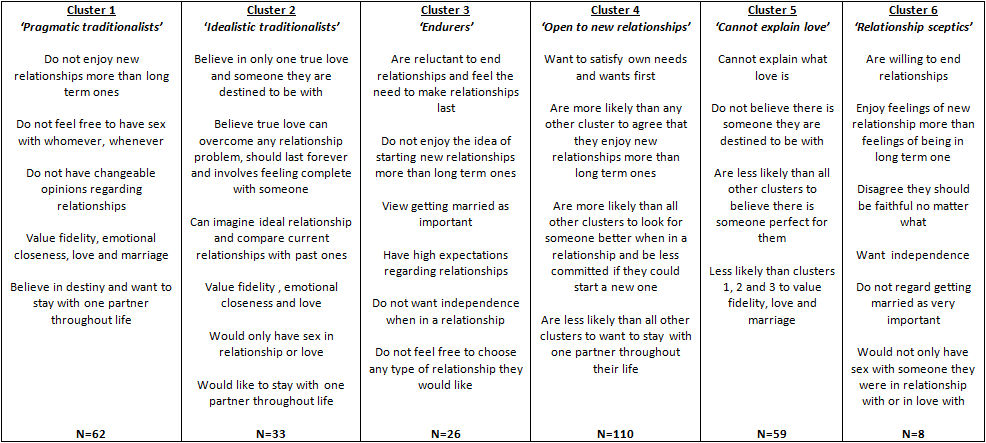

6.4 The most definitive attitudes of those in Cluster 1 are their disagreement with the notions that:

- as long as they are open and honest with one another they can have a happy relationship with anyone

- they enjoy the feelings of starting a new relationship more than the feelings of being in a long-term one

- they feel free to have sex with whomever they want, whenever they want

- their opinions regarding relationships often change.

6.5 In addition they seem to value the importance of fidelity, emotional closeness and love, getting married is very important to them, they believe there is someone they are destined to be with and they would like to stay with one partner throughout their life. Thus, this cluster could be viewed as having both traditional and conservative attitudes towards relationships, most notably centred upon the desire to have long-term rather than short term relationships.

6.6 There are some similarities between the attitudes of those in Clusters 1 and 2 and indeed we would loosely define the attitudes of those in both these clusters as 'traditional'. However, the attitudes of those in Cluster 2 seem more idealistic or 'dreamy' than those in Cluster 1; for example the attitudes held most strongly by those in this second cluster include:

- there is someone they are destined to be with

- there is only one true love for them

- true love can overcome any relationship problem

- true love involves a feeling of completeness with one's partner.

6.7 In addition they are more likely than those in any other cluster to agree that they can imagine their ideal relationship and that they compare their current relationships with those they have had in the past, both of which suggest that the imaginative realm in the context of couple relationships is very important to those in Cluster 2. Based upon these descriptions we argue that while both Clusters 1 and 2 could be loosely labelled traditionalists, those in Cluster 1 could be more specifically defined pragmatic traditionalists while those in Cluster 2 idealistic traditionalists.

6.8 Many of the most definitive attitudes of those in Cluster 3 concern their reluctance to end couple relationships. Those in this cluster are the only ones who, on average, disagree that they would end a relationship if there were more bad things about it than good and that they would end a relationship if they could no longer confide in a partner. In addition, they disagree more strongly than those in any of the other clusters that they would end a relationship if they or their partner changed a lot as people and agree more strongly that they feel the need to make their relationships last as long as possible.

6.9 The most distinguishing attitude of those in Cluster 4 is their agreement with the idea that they would like to satisfy their own needs and wants before those of their partner when making decisions; indeed those in this cluster are the only ones to, on average, agree with this notion. More generally Cluster 4 could be defined as the antithesis of Cluster 3 as the attitudes of those within it seem to reflect an overall desire for new relationships. Those within this cluster are more likely than those in any of the other clusters to agree that while in a relationship they look for someone better to be with, that they would be less committed to a relationship if they could start a new one with someone else and that their relationships are never usually as good as they expect them to be. Further, they are more likely than those in most of the other clusters (all except Cluster 5) to agree that they enjoy new relationships more than long-term ones, although they still disagree with the notion. Finally, those in Cluster 4 are less likely than those in any of the other clusters to agree that they would like to stay with one partner throughout their life, though again on average those in this cluster still agree with this idea.

6.10 There does not seem to be a common theme among the attitudes of those in Cluster 5. The attitude that distinguishes it most strongly from the other clusters is their disagreement with the notion that, if asked, one could explain what love is; indeed those in this cluster are the only respondents to disagree with this statement. Further, those in this cluster are the only ones to disagree that there is someone whom they are destined to be with. Other defining features of this cluster are that those within it are less likely than those within any of the other clusters to believe there is someone perfect for them or believe that any two people could be happy together if their relationship had the right qualities. There are some similarities between the attitudes of those in Clusters 5 and 4; like those in Cluster 4 those in Cluster 5 are less likely than those in Clusters 1, 2 and 3 to value fidelity, love or marriage.

6.11 Cluster 6 is a small cluster (n=8) and many of its attitudes deviate more strongly from the mean than all other clusters. For example, those in this cluster are the only young adults who, on average, agree that they enjoy the feelings of starting new relationships more than the feelings of being in a long term one. Further, it is the only cluster within which people disagree that they should be faithful no matter what and the only cluster within which people tend to disagree that getting married is important to them. Meanwhile those in Cluster 6 are more likely than those in any of the other clusters to want to end a relationship for any given reason and disagree that they would have sex only with someone they were in a relationship with or in love with. Table 4 provides a summary of these six clusters as described above.

| Table 4. Overview of attitudes held by each cluster in six cluster solution (clusters produced via hierarchical cluster analysis, using Ward's method and squared Euclidean measure of distance) |

|

Discussion

7.1 We argue that the cluster solution in Table 3 provides evidence for the relevance of the Romantic Model as an attitudinal type within our sample of 18 to 30 year olds. Cluster 2 could, in fact, be re-labelled 'romantics'. The responses of those in this cluster are almost entirely in keeping with propositions made in the Romantic Model presented in Table 1. Indeed those in this cluster agree more strongly than those in any other cluster with most of the attitude statements that support the model; specifically beliefs in a one true love, the importance of fidelity, the notion of destiny in finding a partner, unconditional love, the idea that true love should last forever and that love involves a feeling of completeness, along with a desire for longevity in relationships, and conservative attitudes towards sex. Those in this cluster also disagree more strongly than those in any other cluster with the statement written in opposition to a fundamental premise of the Romantic Model, that true love is something that grows between a couple over time instead of being felt instantly between them. The only mean scores of this cluster that were not in keeping with the Romantic Model were those that indicate agreement with the belief that any two people can be happy together if their relationship is based upon the right qualities and disagreement with the idea that they have no choice over whom they fall in love with.7.2 As well as agreeing most strongly with nearly all of the statements that support the Romantic Model, those in Cluster 2 agree more strongly than those in any other cluster with the following statements: feeling emotionally close to your partner is essential a good relationship, when couples are truly in love they know and understand everything about one another and when truly in love partners want to tell each other everything. Each of these statements was written to test the Pure Relationship Model and specifically the idea that love is based upon intimacy which is prioritised above all relationship qualities. Further, those in this cluster also agree more strongly than those in any other cluster with the notion, again made in the Pure Relationship Model, that relationships have an identity of their own. Holding each of these attitudes alongside those within the Romantic Model seems coherent enough. What these results therefore suggest is that one cannot distinguish between the Pure Relationship Model and the Romantic Model as attitudinal types but that these specific elements of the Pure Relationship Model are part of the 'romantic type'. Thus, more aptly one might in fact label Cluster 2 'romantic purists'. These results therefore offer no evidence for the Pure Relationship Model as a unique type of attitude, or the distinction Giddens (1992) draws between romantic love and confluent love.

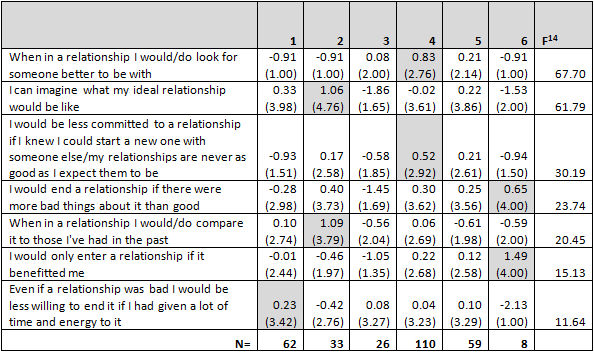

7.3 The results of the cluster analysis offer some evidence for the Investment Model as an attitudinal type. Cluster 4 shows a near consistent tendency to agree with all the statements that support this model; this provides evidence that the propositions made in this model are internally coherent as an attitude type. However the level of agreement in cluster 4 is quite modest and a slight paradox is that although cluster 4 is the most consonant with the model overall, for many of the individual statements other clusters have more consonant responses. To illustrate this finding, Table 5 shows the mean attitude scores for the six clusters only on the attitude items that relate to the Investment Model.

| Table 5. Standardised and unstandardised (bracketed) mean scores of the hierarchical six cluster solution on the attitude items that relate to the Investment Model. Shading indicates the mean response most consonant with the model. |

|

7.4 A complexity with the Investment Model is that agreement with its propositions might be regarded as less socially desirable than with those of the other models, meaning its items might be subject to social desirability bias. Taken a step further, issues of social desirability might mean that some individuals are even unaware of attitudes they hold that are congruent with the Investment Model. The issue of conscious versus unconscious attitudes is not something we deal with in this paper but it is an important caveat to highlight in our exploration of whether the four mentioned theories have any relevance as attitudinal types. We are only exploring this idea through an overt attitude measure; other methods of research (such as measures of revealed preferences) might be better suited to uncovering unconscious attitudes. However, despite this issue, our results do provide evidence that some of our respondents (notably those in Cluster 4) are conscious of, and able to, report agreement with the Investment Model.

7.5 It is interesting that those in the romantic cluster (Cluster 2) have the strongest observed agreement rates with 'When in a relationship I would/do compare it to those I've had in the past'. However, agreement with this statement may have a different meaning for somebody who also agrees with 'I believe there is only one true love for me' (100% strong agreement in cluster 2) but disagrees with 'when in a relationship I would/do look for someone better to be with' (100% strong disagreement rates in cluster 2) compared to somebody with the opposite pattern of responses (such as those in cluster 4). It could, therefore, be that the explicit attitude instrument is not the best way of uncovering these response patterns. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that cluster 4 is by far the largest of the clusters and within such a group even the moderately consonant response patterns indicate that there may be some merit in the Investment Model as an attitudinal type.

7.6 Support from these results for the relevance of the Individualisation Model as an attitude type is also mixed. Table 6 shows the mean attitude scores for the six clusters only on the attitude items that relate to this model. As seen from this table, there is evidence for the model as a type in cluster 6. Those within it agree more strongly than those in any other cluster with the statements that support the model and disagree more strongly than those in any other cluster with statements that contradict the model.

7.7 There are, however, two exceptions to this pattern which regard the statements:

- The most important quality to have in a relationship is love

- I have high expectations regarding my relationships

| Table 6. Standardised and unstandardised (bracketed) mean scores of the hierarchical six cluster solution on the attitude items that relate to the Individualisation Model. Shading indicates the mean response most consonant with the model. |

|

7.8 As well as offering evidence for the existence of the Romantic Model, the Individualisation Model and the Investment Model as attitude types, our results suggest that attitude types in addition to these models do exist. As we have found strongest evidence for the Romantic Model and the Individualisation Model it would be tempting to conclude that there are just two main attitude types that can be neatly positioned within the conservative/traditional (romantic) versus liberal/post-traditional (individualisation) paradigm. Indeed, in discussing the four theories of relationships earlier in the paper we suggest that while individualisation theory offers a theory of post-traditional coupling, romantic theory offers a theory of traditional coupling.

7.9 The results in Table 6, showing Cluster 4 as a less extreme version of the Individualisation Model and Cluster 6 as a more extreme version of it, could lead to the assumption that one could categorise the attitudes of individuals along a scale ranging from conservative/traditional to liberal/post-traditional. However, the six cluster results show a definite distinction between different types of traditionalists: those who have a greater tendency to believe in romantic ideologies and those who have a lesser tendency. Thus, we argue that whether or not someone believes in romantic ideologies adds an extra dimension to the way in which we might categorise attitudes towards relationships in the 18 to 30 age group which goes beyond the traditional/post-traditional distinction; while a belief in romantic ideologies such as love at first sight is associated with conservative/traditional attitudes, the latter can exist independently of them.

Concluding Remarks

8.1 In this paper we have investigated the possibility of treating social theories as attitudinal types. We tested this idea via a case study of attitudes towards relationships among 18 to 30 year olds living in Preston, exploring whether four theories of couple relationships could be mapped onto attitude types identified in the population. The results indicate that the attitudes of young adults cluster into six types but only three of the four theories we test are reflected in those types. Most significantly, the theory of romantic love (Giddens 1992; Jackson 1993) mirrors one attitudinal type in our data. Further, much of the Individualisation Model (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995) was reflected in one of the attitudinal types identified, however this model was not manifest in its entirety. Specifically the belief in love as the most important quality and having high expectations for one's relationships were not correlated with other attitudes of this model.8.2 Investment theory (Rusbult 1980) was shown to offer a whole or complete and coherent set of attitudes in our data though no one cluster was found to agree with this set of attitudes more strongly than any other cluster, limiting the evidence for the theory as an attitudinal type. One might argue that, of all the theories being tested, evidence for the Investment Model (and social exchange theory more generally) would suffer most from social desirability bias as the attitudes contained therein could be viewed as fairly manipulative, e.g. the idea that one would still look around for a better partner while in a relationship. As a result people might be unwilling to admit such attitudes via a questionnaire and might not even be aware of them.

8.3 Most dramatically our results provide strong evidence against Giddens' (1992) theory of the Pure Relationship as a plausible attitude type; our results show that people who have less traditional and conservative attitudes towards relationships do not also value intimacy, which is contrary to the arguments he makes. It is important to again be clear about what we are testing here; there may in fact be evidence for Giddens' (1992) arguments regarding his theory of the pure relationship as universal tendencies in the young adult population. Indeed it might be the case that there has been a rise in the desire for intimacy in the attitudes of young adults. Thus, our results do not dismiss the propositions Giddens makes as having no relevance at all. However, our results do show that as a complete or whole set of propositions his theory does not work.

8.4 On a more general level, our results show that, even within the particular sub-group that we sampled, it is quite clear that attitudes towards relationships are heterogeneous and certainly there is little evidence of the overwhelming influence of one social theory manifested through the attitudes of our study participants. This indicates that a theory of relationship attitude types (or patterns) may well be of value.

8.5 The empirical work reported here could be followed up in a variety of ways. There is an obvious need for a larger scale survey. It would be important to clarify if the cluster structure presented here was replicated in a national or indeed international context. It would also be useful to examine if the structure is robust across age groups or sensitive to other demographics. If so then it would be worthwhile exploring these classes theoretically and testing them directly using confirmatory approaches. Finally, there is an assumption in this initial work that people exhibit only the characteristics of one theory-type. This is driven primarily by the theories being set up as alternatives to one another and this dialectic is in turn represented in our working notion of theories as types. It is, of course, an empirical question whether individuals may be a blend of types or in transition between types over their life course.

8.6 Clearly, there is much more work to do before the notion of the social theory as an attitudinal type has truly demonstrated its theoretical value but with this case study we have demonstrated that it is a framework that merits further investigation.

Notes

1The concept of 'couple relationships' can include many different types of interaction between partners such as marriage, civil partnerships, non-marital cohabitations or Living Apart Together relationships (or LATs). More loosely, a couple relationship might be defined as any pair of individuals who have mutually consenting sex together, even just once as in the case of what might be termed a 'one night stand'. Couples can consist of same, or opposite, sex partnerships and could be monogamous, as neither partner has sexual relations with anyone else, or non-monogamous, as one or both partners have sex with other people. In turn non-monogamy might be openly acknowledged in the case of what might be labelled an 'open relationship' or conducted privately in the case of what might be labelled an 'affair.'2We use the terms 'traditional' and 'post-traditional' throughout this paper. Authors use these terms in different ways, so please note that by 'traditional' (or 'traditional couple') we mean a married, heterosexual couple who live together, while the term 'post-traditional' (or 'post-traditional couple') means any couple relationship that diverts from this form, i.e. non-heterosexual partnerships and non-marital partnerships.

3For a more detailed account regarding the rise of the Romantic Movement and its effect upon emotion see Lupton (1998).

4We use the term imagined behaviour to describe behaviour that exists only in ones thoughts rather than how one actually behaves; it can include the notion of intended behaviour which is how one plans to behave in a given situation, preferred behaviour which is how one would like to behave in a given situation, or expected behaviour which is how one thinks one would behave in a given situation. These three types of imagined behaviour could be the same or different for any given situation, i.e. if one would like to marry but does not expect to.

5Resources were the primary driver for this one city case study selection. It was of some value that the demographic structure of the city's young adult population was broadly comparable to that of the young adult population of Britain as a whole; however, inference to the wider population was not our primary interest here. By the same token we did not employ any post-stratification population weights.

6This is based upon the sampling procedure wherein 150 households are sampled from five streets (150 X 5 = 750) from a total of three SOAs (750 X 3 = 2250).

7Office for National Statistics. Social and Vital Statistics Division and Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Central Survey Unit, Quarterly Labour Force Survey, October-December, 2005 [computer file]. 2nd Edition. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Service[distributor], July 2008. SN: 5429, http://dx.doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5429-1. We used the October-December 2005 LFS because our own data were collected during this period.

8This figure is for the North West of England, it is not possible to calculate a percentage for our specific sample.

9For details regarding the design of the attitude measure, the sampling procedure and the results of the PCA please refer to Watt(2013) 'An Investigation of Attitudes towards Relationships in the 18 to 30 age group', PhD thesis; University of Manchester (Chapters 6, 7 and 8 respectively).

10We considered using LCA for the analyses but deemed the exploratory nature of cluster analysis more appropriate for this (initial) investigation; we were interested in identifying what structure emerged from the data to then look at whether the four theories were reflected in that structure, rather than conducting a direct test of those theories. The main point here is that the set of singular theories may well not form an in toto typology and this would not in itself mean that the notion of a typology was itself ill-founded.

11In practice, the VRC is calculated by summing the F statistics for all variables in a given cluster solution.

12All the F statistics are significant at the 0.01 level. However, the significance levels should not be taken as true tests as the cluster analysis necessarily produces a solution that optimises the F statistics. We also note that because of the clustered sampling method there will be design effects on the variances. However, this is of secondary interest to us here as we are not primarily interested in the statistical distinguishability of the clusters but whether the interpretation of each optimal cluster corresponds to any of the four theories we are investigating.

13All significant at the 0.01 level

14All significant at the 0.01 level

15All significant at the 0.01 level

References

AJZEN, I. (2005) Attitudes, personality and behaviour. Maidenhead, Berkshire: McGraw-Hill.ALBARACCIN, D; Johnson, B.T & Zanna, M.P. (Eds.) (2005). The handbook of attitudes. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

BALES, R.F. & Parsons, T. (1956) Family: socialization and interaction process. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

BECK, U. & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (1995) The normal chaos of love. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

BOHNER, G. &Wanke, M. (2002). Attitudes and attitude change. New York: Psychology Press.

BURKITT, I. (1997) 'Social relationships and emotion', Sociology, 31(1) p. 37-55. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038597031001004]

CALINSKI, R.B. & Harabasz, J. (1974) 'A dendrite method for cluster analysis', Communications in Statistics, 3(1) p. 1 - 27 [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03610927408827101]

ENGELS, F. (1884) The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. London: Penguin

GIDDENS, A. (1992) The transformation of intimacy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

JACKSON, S. (1993) 'Even sociologists fall in love: An exploration in the sociology of emotions', Sociology, 27(2) p. 201 - 220 [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038593027002002]

LA PIERRE, R.T. (1934) 'Attitudes versus action', Social Forces, 13(2) p. 230 - 237 [doi://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2570339]

LUPTON, D. (1998) The emotional self. London: Sage.

MURDOCK, G. (1949) Social Structure. New York: Macmillan Co.

OPPENHEIM, B. (1988) 'Attitude measurement' in Doing Social Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

RUSBULT, C. (1980) 'Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model', Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16(2) p. 172 - 186. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4]

TURK, H. & Simpson, R.L. (Eds.) (1971). Institutions and Social Exchange: The Sociologies of Talcott Parsons and George. C Homans. New York: Sociological Inquiry.

WATT, L. (2013) An Investigation of Attitudes towards Relationships in the 18 to 30 age group. PhD Thesis: University of Manchester.

ZARETSKY, E. (1976) Capitalism, the family and personal life. New York; London: Harper & Row.