Personal Life, Pragmatism and Bricolage

by Simon Duncan

University of Bradford

Sociological Research Online, 16 (4) 13

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/16/4/13.html>

10.5153/sro.2537

Received: 15 Jun 2011 Accepted: 3 Nov 2011 Published: 30 Nov 2011

Abstract

Individualisation theory misrepresents and romanticises the nature of agency as a primarily discursive and reflexive process where people freely create their personal lives in an open social world divorced from tradition. But empirically we find that people usually make decisions about their personal lives pragmatically, bounded by circumstances and in connection with other people, not only relationally but also institutionally. This pragmatism is often non-reflexive, habitual and routinised, even unconscious. Agents draw on existing traditions - styles of thinking, sanctioned social relationships, institutions, the presumptions of particular social groups and places, lived law and social norms - to 'patch' or 'piece together' responses to changing situations. Often it is institutions that 'do the thinking'. People try to both conserve social energy and seek social legitimation in this adaption process, a process which can lead to a 're-serving' of tradition even as institutional leakage transfers meanings from past to present, and vice versa. But this process of bricolage will always be socially contested and socially uneven. In this way bricolage describes how people actually link structure and agency through their actions, and can provide a framework for empirical research on doing family.

Keywords: Bricolage, Agency, Individualisation, Families, Pragmatism

Introduction

1.1 People usually make family decisions pragmatically with reference to their material, social and institutional circumstances. This pragmatism assumes some sort of power in making practical decisions and carrying out everyday tasks – in other words agency operates within constraint. Unfortunately, much of social science has a romantic view of agency as dominantly purposive and conscious, neglecting the practical, habitual and unconscious. This is evident in individualisation theory. Moreover, the structuration problem – how structure and agency interrelate through people's actions - has not gone away. Consequently we need to develop a framework that goes beyond definitional notions of praxis or habitus to describe how people actually do connect structure and agency through their behaviour. I take the idea of institutional bricolage as a means of doing this, and as a way forward in family research. In the next section I set the scene by illustrating how people behave pragmatically in personal life, using the examples of mothers' orientation towards paid work, and less traditional family forms. Based on these examples, section 3 briefly revisits ideas of agency and structuration, and section 4 develops the notion of institutional bricolage as one solution. Section 5 concludes with some remarks on bricolage and family research.2. People behaving pragmatically

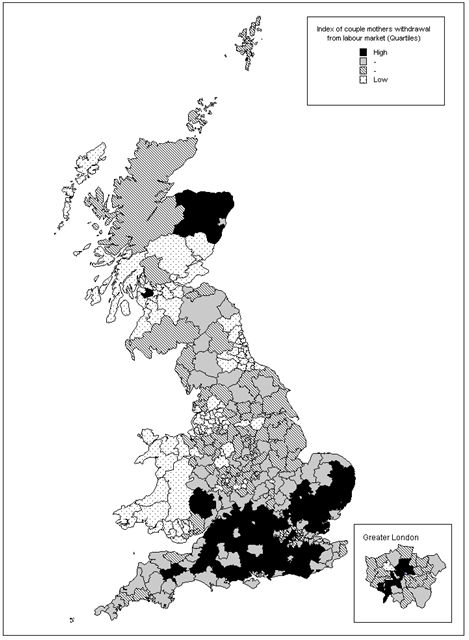

2.1 We know that mothers in Britain are more likely to withdraw from a worker role than women of a similar age who are not mothers; mothers are likely to see childcare as their chief role and either withdraw from employment altogether (especially if the children are below school age) or work part-time around school or nursery / childminder hours. Male partners, conversely, are likely to expand their 'provider' role in full-time work. A few years ago Darren Smith and myself mapped local variations in mothers' relative withdrawal from the worker role by local authority area, using 2001 census data (Duncan and Smith 2006). We called this the 'motherhood employment effect', see Figure 1.| Figure 1. Motherhood Employment Effect, Britain 2001 |

|

2.2 What we found initially surprised us. It was mothers living in higher income areas, such as the richer parts of the South East, who were most likely to withdraw from the worker role. Those mothers with apparently most room for manoeuvre (in that they can better afford childcare and transport costs, probably possess more human capital, with more job opportunities, higher potential wages, and higher earning partners) were the more likely to act 'traditionally' as 'proper mothers' - as conventionally understood in Britain - and leave the worker role. It was mothers in lower income areas, such as those in former mining and heavy industry regions like north-east England or South Wales, who were more likely to act less traditionally in combining a worker role with motherhood. This is presumably because lower income mothers had less choice in exercising the 'proper' way of combining motherhood with paid work, and were forced to act 'improperly' for economic reasons. Rather than decreasing over time, this 'motherhood employment effect' seemed to have increased since 1991.

2.3 This socio-spatial patterning of the motherhood employment effect shouldn't have surprised us, because this fits in with previous ideas that Ros Edwards and myself developed about 'gendered moral rationalities' in our work on lone mothers and employment (Duncan and Edwards 1999). Mothers held different moral views, which were developed and maintained socially in particular settings, about how to properly combine motherhood with paid work. These then interact with the more economic considerations of what jobs and wages are available. If circumstances permit, mothers will attempt to 'properly' mother as they see it. Higher household incomes –from male partners a well as their own employment – will enable them to better achieve this 'proper' outcome. For most mothers in our study, this meant withdrawing from the worker role, although some groups of mothers held alternative ideas of proper motherhood which involved a worker role. Most Black mothers we interviewed, for instance, held views which saw full-time employment as part of good mothering.

2.4 A telling instance is what happens to the employment activity of lone mothers who re-partner. We used Longitudinal Study data (which traces individuals between censuses) to examine this from 1981-91 (ibid). On average, such re-partnered mothers would have acquired greater household income, and also access to the new male partner for some extra childcare time; certainly their existing children would be older. However, despite these greater resources and lower constraint levels, White mothers in the sample tended to leave existing paid work, especially full-time work, and move into part-time work and unemployment. In contrast, Black lone mothers tended to move from unemployment and part-time work into full-time work. Both ethnic groups of mothers used their increased resources to better support the (alternative) combination of motherhood and paid work they took to be morally correct. This process of using the economic resources available, to better promote what is socially seen as 'proper mothering', fits in with the geography in the 2006 study, as shown in Figure 1.

2.5 Note that acting 'properly' as a traditional mother does not only mean a focus on personal childcare; usually a traditional gendered division of labour at home is also included. Not only this, but the recent development of an 'equality illusion', whereby choice and empowerment have been co-opted by the beauty and sex industries so that women can 'choose' to look and act as men desire (Banyard 2010, Walters 2010), has resulted in a new glorification of the perfect wife; the culture of domestic goddess in the kitchen and sexy partner on display – as well as 'proper mother' at home. This demands more time and work, for example, extra cooking, fitness classes, tanning sessions and so on. Full-time employment becomes all the more difficult. Maybe this explains the intensification of the geographical pattern between 1991-2001.

2.6 Decisions about the balance between paid employment and unpaid work are not 'economically rational', but acted according to collective ideas of what is deemed socially proper, and this varies by social group and setting. Nor, as later work on partnered mothers employment and childcare decisions suggested, is there necessarily much reflection or negotiation about this. Rather there is often an acceptance, often a routinised or even an unconscious acceptance, of taken for granted ideas about what is natural and expected. For example, for many mothers’ it is seen as natural that men need the stimulation of paid work and are psychologically unsuited for childcare (Duncan et al 2003, 2004).

2.7 All this contradicts theoretical ideas about individualisation, reflexive modernity and the new democratic family, such as those advanced by Tony Giddens, Elizabeth Beck-Gernsheim and Ulrich Beck. Rather, as mothers gain greater access to resources, and in principle gain more choice and more room for manoeuvre, then they are more likely to behave in accordance with what they experience as 'traditional' gender normatives. Nor do such behaviours seem to enhance any reflexive project of the self. Rather, they seem to be structured by external social norms concerning obligations to others, and to be developed in the context of local conditions and particular social reference groups. This development can be habitual or even unconscious. While there may be greater freedom for manoeuvre than before for many mothers, this does not automatically equate with individualisation. Rather, if they can, mothers appear to 'put family first'. Individualisation theorists confuse what people can potentially do (create individual self–projects) with what they actually do (relate to others in more taken for granted 'traditional' ways).

2.8 We can find more examples of this in other areas of personal life like cohabitation, living apart together and different attitudes about family and relationships, which I explore below. For example, the seemingly inexorable rise of unmarried cohabitation is often portrayed as one key element of the 'breakdown of the family', or as representing the rise of 'liquid love'. These commentators assume both lack of commitment and selfish individualism. Alternatively some individualisation theorists can see cohabitation as a trend index of the 'pure relationship', which leaves behind traditional ideas of romantic love and family commitment, and is instead based on purely consensual commitment in which partners stay together in so far as their autonomous self-development projects and erotic needs are met. But contradicting both sets of assumptions, empirical evidence suggests that unmarried cohabitants are just as committed (or uncommitted) to their partner and children as married partners are, if we compare like with like controlling for age and income (Lewis 2001, Barlow et al. 2005). Most continue to adhere to traditional notions of marriage, love and commitment (ibid, Carter 2010). Not surprisingly, then, cohabitants are just as traditional as married couples in everyday life, for example in sharing money and household tasks (Vogler 2005).

2.9 Moreover, while some cohabitants consciously choose a principled alternative to marriage, most simply see cohabitation as similar to, and practically the same as, marriage in everyday life (cf Syltevik 2010 on Norway as 'cohabitation land'). Most unmarried cohabitants are not at all opposed to marriage, but see this as an ideal (Duncan et al 2005). Indeed many cohabitants imagine themselves as marrying at some future time - although more accurately we should say 'wedding'. For most the wish is to enjoy an ornate white wedding (Carter 2010), which can publically – and traditionally - confirm their successful adult relationship and social position. In their eyes they are as good as married already given the 'lived law' of everyday life in everyday institutions like schools, workplaces or hospitals where cohabitation is equated with marriage. Hence it is not the marriage as a legal relationship which is pressing or desired, but the wedding. Consequently the 're-invention' of the Victorian white wedding for cohabiting couples after the 1980s[1], in contrast to the simple, short and cheap weddings of most people in the 1940s and 50s, when legal marriage was socially necessary if a couple were to live together and have children. Tradition, in the form of the white wedding, is thereby idealised and used as a legitimating and positioning resource. A corollary of this is the 'marooning' of ossified symbols of this tradition in new contexts (Charsley, 1992) - like the wedding cake. The cake invokes tradition, where the rite of joint public cutting by bride and groom seems to represent the entrance of the couple into marriage as a different state. At the same time, however, the wedding cake has been 're-invented' with ornate styles and embellishment showing personal difference[2]. 'Living Apart Together' (LAT) is sometimes seen as going even further down this individualisation road as an alternative family form; in this view the partners can most easily have both intimacy and autonomy (Levin 2004). But the evidence suggests that LAT is usually not some conscious 'alternative' to coupledom, or a move 'beyond the family', but rather a more pragmatic response to circumstances with 'traditional' ideas about families, coupledom, and marriage as a continuing framework for behaviour (Duncan and Phillips 2010).

2.10 What about earlier decades, for surely the way people behave in personal life has changed immensely since the supposedly 'traditional' 1950s? But, if we 'standardise' for the issues of the time, the way in which people make intimate decisions about personal life seem more or less the same as today. Here I draw on research comparing public ideas in Britain about family and intimate life for 1949/50 compared to 2006 (Duncan 2011)[3]. For both 1949/50 and 2006, the married, older and religious were more 'traditional', and the young and professional were more 'progressive'. Only a minority, in either the 2006 or 1949/50 samples, acted according to some 'progressive' position. Similarly, only a few in either period appeared to subscribe to externally imposed 'tradition'. Rather the bulk of both samples held pragmatic views of what was reasonably proper and possible in the circumstances of their time and place. Ideas about pre-marital sex in the 1949/50 give a good example. In principle, most respondents thought this was a bad thing; sex should take place within marriage. But only a few thought such behaviour absolutely wrong, mostly the religious and particularly clergymen. Similarly, a few were particularly 'modern' in seeing pre-marital sex as fine, even useful, as long as this was a democratically arrived decision. Rather, most people pragmatically accepted that pre-marital sex might well take place and would tolerate this lapse for 'serious' couples, who were in love but for some reason unable to marry just then. Similar evidence is found in other historical family research (e.g. Smart 2007). The issues might have changed, but the contemporaneous distribution of modern, traditional, and pragmatic seem similar.

2.11 In all these examples we find people usually making family decisions pragmatically, with reference to relationships, social norms, 'lived law', and the presumptions of particular social groups in different places. Nor, it seems, were particular historical periods either hidebound by tradition or, alternatively, filled with self-reflexive individualisers. Rather, the examples suggest that people adapt to their circumstances through invoking and re-inventing tradition, often habitually and unconsciously, and nearly always in interaction with other individuals and social groups, This is in some contrast to the assumptions made by individualisation and rationality theories. The question now is what do we do about this? Do we keep on heaping up empirical counter-evidence, or attempt some sort of alternative theorisation around 'pragmatism'. I attempt to initiate the latter in the rest of this paper.

3. Pragmatism as agency: from structuration to habitus

3.1 What is this 'pragmatism' which is seemingly pervasive in everyday personal life? Pragmatism assumes some sort of power in making practical decisions and carrying out everyday tasks - in other words agency. As my examples above have shown, this is a qualified power exercised by agents in relation to others in social contexts. Consequently, the idea of pragmatism takes us back to the idea of agency within constraint.3.2 Unfortunately social scientists often make assumptions about agency that are problematic in that individual motivations and actions become equated with purposive and conscious action (Cleaver 2002). Giddens is an influential example. In his 'individualisation' work (e.g. 1992), he has become increasingly optimistic about the possibilities for instrumental, empowering and reflexive individual agency to overcome constraints –which in any case are supposedly withering away. Hence Giddens' deduction of trends towards 'pure relationships' and 'family democracy', trends which empirical research has found so hard to locate (e.g. Jamieson 1998, Ahlberg et al 2008). At the other, pessimistic, extreme of individualisation theory Bauman nevertheless makes similar assumptions about agency; cultural codes and rules are increasingly loosing their grip and hence agents are now 'abandoned to their own wits' (2003, viii) even if this instead leads to 'inevitable personal miseries' (Smart 2007, 64). Family sociology is no exception to this overemphasis on purposive agency. Famously Morgan (1996) redefined family studies away from family as a given institution, 'a thing like object' which remained outside its members' influence, and towards family as a set of flexible practices and interactions – 'family is what families do'. While this concept implies the importance of routinised and unconscious agency, in practice this has usually been interpreted as meaning what families consciously and purposively do. The recent emphasis on 'relationality' in family studies (e.g. Mason 2004), although partly a reaction against individualisation theory, is an example. While now seeing that people's relationships with others play a considerable part in their reasoning around personal decisions, this reasoning is still 'intentional (and) thoughtful… which they actively sustain, maintain or allow to atrophy' (Smart 2007, 48).

3.3 Ironically, the earlier work of Giddens (e.g. 1984) can provide a corrective, where he conceives of three types of consciousness – discursive consciousness (where agents are able to bring actions and beliefs into discursive scrutiny), practical consciousness (taken for granted everyday practices that are so part of habit, routine and precedent that they are rarely scrutinised or reflected upon) and the unconscious ('irrational' thought and emotions like fear or desire). The notion of agency in family studies has usually overemphasised discursive consciousness and underplayed the constitution of agency through the practical and the unconscious. This tendency is exacerbated by the dominant methodologies employed – the semi-structured interview and the survey questionnaire. Both methods largely assume discursive consciousness as decisive, and operate on this level. But not all individual acts are the results of conscious strategy; many result from habit or routine, from the unconscious motivations of conscious actions and the unconscious self-disciplining of agents, and from the internalisation of hegemonic norms. Much of everyday practice – of pragmatism – will be non-reflexive, routine and structured. Mothers' choices in combining employment and caring work is just one example (see figure 1). While we usually think of change as generated through purposive action, this implies that change can also result from routinised acts. Methodologically, this also implies research techniques which better access the habitual and assumed – such as biographical interviews or observation.

3.4 So much for 'choice' – but what about 'constraint'? For we should remember that while to be an agent is to make a difference and to exercise some sort of power; how much power and difference depends on relations with others through institutional structures (either formal and informal). It is these relations that allow, or restrict, an agent's access to and use of resources. Some agents are better placed to deploy resources than others; indeed some may dominate social behaviour, while the access of others is limited. Again Giddens provides a useful guide in distinguishing between what he calls allocative resources (command over things, e.g. means of production) or authoritative resources (command over people – e.g. in organisations and institutions). Authoritative resources include moral world views – strongly gendered, socially stratified ideas about the proper behaviour and the rightful place of individuals with different social identities. So Ros Edwards and myself found that some mothers with a high level of human capital, and hence theoretically good opportunities for continuing their careers in taking highly paid work, in practice referred to particular gendered moral rationalities and social networks that precluded this and instead emphasised being an unemployed mother at home. Hence they did not pursue their relatively achievable career opportunities. Conversely, some mothers with low human capital – and hence from the discursive, rational economic point of view most likely to give up employment - in practice referred to alternative gendered moral rationalities and social networks that emphasised mothers' full-time work, and hence they continued in long hours of employment (Duncan and Edwards, 1999).

3.5 'Family' agency is indeed relational, where the 'power ' to act is shaped by social relations to others. However, this power is often routine and/or unconscious, rather than consciously purposeful. At the same time this relationality is not just with intimate others (although this may dominate people's discursive agency) but with others in institutions, both formally and informally, and both individually and collectively. As Mary Douglas (1987) famously put it, institutions 'think' on our behalf. In so doing social institutions (the accepted ways of thinking and doing) also constrain us, often invisibly. Cohabitants may discursively and intimately decide to live together through conscious feelings of partnership and commitment, but unconsciously and collectively act through ideas of romantic love and adult propriety maintained through the institution of marriage. And the mortgage provider will treat them as married. So while individuals possess agency, this will be often prescribed or limited by the culture in which they find themselves, and by other agents. In this way structures shape the opportunities and resources available to individuals, hence their agency is not simply a matter of choice.

3.6 Women's choice between paid employment and unpaid caring work is not just a matter of lifestyle preferences as Catherine Hakim (2000) would have it - where she imagines no major constraints limiting or forcing choice in particular directions, and where individual preferences can be, and are, fully realized. In his laudatory introduction to Hakim, Giddens is even moved to claim that 'we can no longer learn from history', where 'individualisation has been the main driving force for change in late modern society' (Giddens 2000, vii). But nor are these choices simply a structural outcome of 'patriarchy at work' (Walby 1986). Agency operates somewhere in between. Re-enter, ironically enough, Giddens' earlier concept of structuration. Re-enter also an old question – how far can agency generate transformation, and how far it is subjected to the disciplines of social norms, sanctions, and the resources available? Think of those mothers in west London (see Fig 1).

3.7 Structuration theory, while heuristically valuable, leads to an explanatory impasse. How does this work in practice? Researchers usually end up stressing either agency or structure, as the examples of Hakim and Walby cited above caricature. Gross (2005) tries to square this circle by thinking of two types of structure. 'Regulative traditions' are those essentially external to the agent, with transgressions punished by communities or state authorities (e.g. living together unmarried in 'traditional' society). Alternatively 'meaning constitutive traditions' operate internally to the agent, constituting her identity as cultural meanings are passed down between generations. An example is when cohabitants continue to act with reference to ideals around marriage. This distinction also allows Gross to have his individualisation cake and eat it – unlike Giddens, he does not have to entirely retreat from structure. Individualisation, understood as 'detraditionalisation', does indeed occur as regulative traditions decline, but because of the continuing strength of meaning-constitutive tradition this does not mean 'unbounded agency and creativity' (ibid, 288). There is not, contra Giddens in his 'individualisation' work, a simple polarity between 'traditional' and 'modern' society, still less traditional and modern people. We are still subject to 'sedimented habituality' and 'intersubjectively shared traditions' (Gross, 2005, 293), so that many everyday actions are not that different to those in the past. So now people can live together unmarried, as community and state regulative tradition weakens in 'modern' societies, However, marriage will remain a social ideal and model for action – even for the unmarried - given that agents' actions continue to be shaped by the meaning constitutive traditions of romantic love and couple commitment. In this way Gross can retain individualisation theory but also encompass its empirical critiques (see also Smart 2007 who employs Gross in this way).

3.8 Gross makes a useful observation in signalling the importance of routinised and habitual practices, and in debunking the 'traditional /modern' polarity. But to my mind his central analytical device does not work; it re-introduces another polarity. Indeed, Gross himself admits that the distinction between the regulative and meaning-constitutive traditions is 'always blurry in concrete empirical cases' (op cit, 296). For example, the cultural tradition of romantic love can invoke considerable regulative activity, while marriage as a regulative institution has hardly lost its cultural leverage. Both sorts of tradition (as distinguished analytically) are equally subject to structuration. The structuration riddle has not gone away through the device of 'analytically' separating two sorts of structure. Rather it is the earlier Giddens (1984) who gives the better lead in his idea of 'praxis'- agency originates in the individual's skilful performance of everyday life and the creative use of the resources available. But it is Bourdieu who has gone furthest in resolving this structuration problem, or at least inspired most acclaim – 'habitus' is the answer.

3.9 Bourdieu starts from the basic observation that even in our most conscious and reflective thoughts we cannot but take some things for granted. As Francois Collet (2009) points out, this would have the appearance of a truism, except that it goes against the tenets of much of social science with its underpinnings of rationality – individualisation is perhaps the latest sociological example (Duncan et al 2003). It is 'nonsensical' to imagine that any action can be fully "reflexive" in the sense of a complete break with all prior traditions and habits (Gross 2005). Hence, a corrective is found in Bourdieu's idea of 'habitus':

'lasting dispositions or trained capacities and structural propensities to think, feel, act in determinate ways, which then guide [agents] in their creative responses to the constraints and solicitations of their extant milieu' (Wacquant 2005, 316).

3.10 People follow rules without referring to them; their view of the world and their actions are framed by their past experience and current social position, and so they develop by necessity a practical sense of orientation that guides them in their actions. The taken for granted character of this does not call for examination by the agents themselves because the choices produced by this practical sense seem self-evident, beyond questioning. Agents might even consider as normal or fair situations that may seem unfair or unbearable to external observers. Note however, that this habitual and unconscious component does not mean that agents necessarily reproduce past behaviour, for they must take into account changes in the social fields in which they are situated. As Collet (2009) observes, this is a justification for using the term 'habitus' rather than just simply 'habits'; agents cannot simply be reduced to the rules. Hence agents both follow rules and exercise agency; they combine discursive, practical and unconscious agency.

3.11 The notion of 'gendered moral rationalities' can, with hindsight, be seen in this way (Duncan and Edwards 1999, Duncan et al 2003)[4]. Mothers develop employment – caring combinations with reference to taken for granted ideas about proper behaviour as a mother, ideas which are produced and maintained in particular social and spatial contexts. But as the example shows, these particular agents did not simply or necessarily reproduce past behaviour (of their own mothers, for instance), because they had to take into account changing circumstances – in this case the changing structural landscapes of labour markets, social infrastructure and social policies. For example some mothers needed employment for longer hours than their ideal suggested, and they extended the ideas of 'good mothering' – or at least 'good enough mothering' to the supposedly one to one emotional support that childminders might extend to their children as some sort of replacement mother (Duncan et al 2004). This re-adaption of habitus reminds us of Bourdieu's maxim (eg Bourdieu 1977) that everyday life involves 'necessary improvisation'.

3.12 Habitus takes us further, then, in tackling the structuration problem, of allowing agents both creativity and habituation. Frustratingly, the problem of process remains – just how does habitus work, how do agents both follow rules and exercise agency? How, then, does the necessary improvisation of everyday life actually proceed? Hence, in mirror image, the particular problem in attempting to explain how mothers' gendered moral rationalities worked.

3.13 A first attempt was to follow agents' biographical and relational histories in detail (Duncan 2005). For example why did Christina (one of the interviewees) stay in badly paid, semi-casual employment, despite her aspirations for something better, her strongly held belief that mothers needed an 'outside life', and evidence of considerable application and ability in combining employment with caring tasks across the generations? Why did she keep having 'unplanned' children as soon as her position allowed some possibility of career improvement? Interview analysis suggested both a strong identification with her parents' 'traditional' understandings of family, but simultaneously combined with antipathy to her own early family experience as an only child, buttressed by her husband's traditional view of gender roles. All this seemed to cement her identity as stay at home mother with new babies. Hence she could not actualise her own career ambitions and in this way culturally reproduced her disadvantaged class and gender position. In contrast, while Carrie shared Christina's 'primarily mother' gendered moral rationality, she nonetheless held down a demanding full-time job as head teacher. Her moral understandings that good mothers stayed at home stemmed, it seemed, from identification with her own mother's cultural understandings. But at the same time she was able to pursue a full-time employment career because her partner, Pete, acted and had identified as full-time 'mother-substitute'. In turn, this followed his earlier immersion in the culture of a feminist commune, shared with Carrie, and now buttressed by her (and his) continuing feminist politics.

3.14 These sorts of story can be fascinating, but essentially this approach results in an explanatory dead end. This is because it ends up with a mass of individual explanations of particular stories; the only overall explanation possible is a type of aggregate generalisation. Typically, this would stress factors like the mothers' (non)identification with their own parents, the biographical development of their social identity, and the power relations amongst the contemporary parents (ibid). The psycho-social approach takes this immersion in personal detail even further, and at first sight does appear to reach those parts that other theories cannot. This is not just because of its close accounting of how individual situations develop, but because it refers to psychoanalytic ideas about causal process in doing so (e.g. unconscious identification or attachment). Respondents' stories are first elicited, and then interpreted to reveal what lies behind them. Working with and reworking an individual's social and psychic development – their personal and relational 'tradition' - is central to this process. In this way an explanatory generalisation seems more possible, as well as the collection of empirical detail. Together with the use of more in-depth, and more open, interview techniques (often the BNIM method, Wengraf 2001), this explains some current popularity in research on family and intimate lives (e.g. Roseneil 2006, 2009). But several difficulties emerge. First, the approach exacerbates the problem of creating a mass of specific detail on particular cases. Second, social relations in collectivities and institutions are neglected. It is the agent's unconscious which is prioritised over both practical and discursive consciousness. Useful though the psycho-social approach is in recognising the unconscious and non-discursive (and hence also providing a complimentary critique of individualisation theories), in my view it over-emphasises the individual's 'interior' agency and personal 'tradition', and hence restates the structuration problem in a different guise.

3.15 So far, something of an impasse. We still need a means of operationalising Giddens' 'praxis' and Bourdieu's notion of the 'necessary improvisation' of everyday life. I think the notion of 'bricolage' can perform this function as a 'middle range' theorisation of how agency is socially institutionalised and practised. Ironically enough, Marx implied a similar resolution in his well known illustration of the 'structure -agency' problem in 1852, in his commentary on Louis Bonapatre's coup of the '18th Brumaire'. First, in an oft quoted passage, he delineates the structuration problem:

'Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.' (Marx, 1934, 10)

3.16 But in the very next sentence Marx observes how a process of bricolage, the improvised adaption from earlier practice and understandings, gave agents a means to act:

'And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honoured disguise and borrowed language' (ibid).

4. Bricolage as understanding pragmatism

From 'intellectual bricolage' to bricolage as institutionalised agency

4.1 Travelling around France you come across large shed retail outlets offering 'bricolage'; these are Do-It-Yourself (DIY) stores. Bricoleurs, the people who go to these outlets and do the jobs, might be translated as 'handymen', or even 'bodgers'. But in fact this real life metaphor is apt, bricolage in theory concerns the everyday practice of DIY and muddling through – but socially and collectively at large, rather than just individually for home improvements4.2 The social science appropriation of the term seems to have started with Lévi-Strauss, and has been taken up extensively as a metaphor in the visual arts and architecture (where DIY is both practical and theoretical) and hence in cultural studies. Bricolage as an explanatory device has also been used in research on management and entrepreneurship, and on information systems. This is because of the inadequacies of dominant business and information theories that focus on the rationality and irrationality of choice and resource allocation. Rather, empirically, managers and entrepreneurs are found to 'invent' resources from available materials, to make do with what is to hand, and so create something from 'nothing'. Similarly policy is not derived from a 'rational' evaluation of evidence; rather policy makers piece together, assemble and make sense of various sources and types of information, often second hand, to create something new. Here, however, I raid Frances Cleaver's (2002, 2011) formulation of 'institutional bricolage' in development studies. In this formulation there is a particular focus on social institutions in carrying through social and economic development, and it presents therefore a more sociological use of bricolage.

4.3 Cleaver starts from Mary Douglas' extension of Levi-Strauss's concept of 'intellectual bricolage' to institutional theory, in contradiction to theories of rational choice and action (Douglas 1973, 1987). 'Institutions do the thinking' on behalf of people, and these institutions are constructed through a process of bricolage – the gathering and applying of analogies and styles of thought that are already part of existing institutions. Social formulae are repeatedly used in the construction of institutions, thereby economising on cognitive (and social) energy by offering easier classification and legitimacy. This also implies 'institutional leakage' whereby 'Sets of rules are metaphorically connected with one another, and allow meaning to leak from one context to another along the formal similarities that they show' (Douglas 1973:13). This is a sort of institutional DIY rather than the more explicitly conscious and rational form of institutional engineering or design so often assumed.

4.4 Douglas emphasises the sameness and constraint of this form of institutional development, thus 'the bricoleur uses everything there is to make transformations within a stock repertoire of furnishings' (Cleaver 2002, 66). Cleaver departs from Douglas in emphasising agency as critical in shaping and reshaping institutions. People consciously and unconsciously draw on existing social and cultural arrangements - existing institutions, styles of thinking, social norms and sanctioned social relationships - to 'patch' or 'piece together' institutions in response to changing situations. These institutions are therefore neither completely new, nor completely traditional, but rather a dynamic mixture of the 'modern' and 'traditional', and the 'formal' and 'informal'. At the same time, different bricoleurs apply knowledge, power and resources in different ways, and there is variability in the capacity of individuals to act as bricoleurs. Some agents have much less capacity to act in the resultant structure than others – although all retain the potential to act. In this way there is a differential moulding of institutions by bricoleurs, and of bricoleurs by institutions. Cleaver coins the term 'institutional bricolage' to describe these processes, and goes on to demonstrate them empirically in case studies of resource use, water supply, and livelihoods (Cleaver 2012).

4.5 Individualisation theorists also pick up on the 'DIY' analogy for social action. But they do so in a completely different way, which emphasises individual and discursive agency in an open social world divorced from tradition. Thus Beck and Beck-Gernshein assert that 'normal' biographies of love are being replaced by 'do-it-yourself biographies'. But for them:

'biographies are removed from the traditional precepts and certainties, from external control and general moral laws, becoming open and dependent on decision-making, and are assigned as a task for each individual' (Beck and Beck-Gernshein 2002, 5; see Gross 2005).

4.6 Giddens takes this even further, for him 'the past is not preserved but continuously reconstructed on the basis of the present' (Giddens 1994, 63). The hallmark of tradition, then, is the amount of energy devoted to such a project – and this implies a large expenditure of social time and labour. Clearly, these metaphors are quite different from Cleaver's more developed and operational use of bricolage. For her bricolage is deeply social, often hidden and non-reflexive, usually unequal, and the past is 're-served' through its improvised adaption in the search for a low expenditure of social energy. This development of 'institutional bricolage' appears to fit much better than 'Individualisation' with the empirical examples of 'pragmatism' discussed in section 2.

How bricolage works

4.7 How then, does institutional bricolage work in practice? Drawing on Cleaver and others using her work (e.g. de Koning 2010), we can draw out a list of principles emerging from the empirical work on development.

4.8 An underlying tenet is that people are highly likely, when acting either consciously or unconsciously in responding to new circumstances, to reduce both their own cognitive effort and the social energy involved in negotiating with or otherwise relating to others. This is for two main reasons. First, it takes some effort, in terms of time and social effort, to develop and maintain adaptive practices; completely new institutions take most effort of all to set up and run, and correspondingly the probability of a successful outcome will be less. Secondly, our own cognitive and social capacities are limited (cf Martin 2010). The obvious way of both minimising cognitive and social energy, and enhancing the probability of success, is to draw on and adapt from well-known norms, customs and practices. People can go along with the new arrangements without having to cognitively calculate and socially negotiate every single interaction. This can hardly be a rational and reflexively discursive practice. As John Martin (2010) engagingly puts it, we should better view 'culture' as a vast junkyard into which we foray from time to time in the attempt to find something useful, where most is left unused and unshared, and where what is used is selective, simplified, even idiosyncratic. Note however, that this 'traditional' resolution might not be the most socially efficient in the long term; people still have to work at using the adaption which, given its patchy compromises, may well be sub-optimal in a 'rational' sense.

4.9 This process of conserving social energy links in with a principle of social legitimation. People need existing reference points to make sense of their adaptive behaviours, both to themselves and to others. It is far easier if what they are doing is generally accepted as a 'right' and 'sensible' way of doing things, even better if the new adaption appears 'legitimate' or even 'natural'. Bricolage, then, can become part of the 'naturalisation' of social life. The example discussed above of seeing unmarried cohabitation as 'DIY' marriage is a case in point; in this case it is easier to rest new behaviour – openly living together unmarried - upon pre-existing and accepted institutions like marriage, and pre-existing norms like romantic couple love and the nuclear family. Think of the travails of various 'new age' communes, which self-consciously attempted to replace all of these.

4.10 For the communards conventional families were failures, excessively closed and rigid, instead they would create family life based on openness and non-possessive attachments. But their communes were hard to maintain, both because of a lack of social legitimacy as well as the vast amounts of social energy consumed in running them. For example, McCulloch's 1970s study found only 5 out of 67 communes survived 5 years (McCulloch 1982). The amount of relationship work was too great, communication was too difficult, and excessive bureaucracy choked everyday life. In addition, large amounts of capital and emotional investment were required, and this is one reason why class and gender inequalities were reproduced. Indicatively, communes with a religious basis – that is with pre-existing traditions – were the most likely to survive. Nor were communes able to reproduce intergenerationally and the status of children was deeply problematic. Tim Guest's (2004) childhood autobiography of his early life in various Osho movement communes, which among other things involved living with '200 mothers' – but little contact with his biological mother - has been described as a 'rightly disturbing read of malignant child neglect by people who sought a heaven, but made a hell' (Kirkus review, 15.11.2004). In contrast 'problem families' are seen as an issue about dysfunctional people as they fail to live up to the assumed natural ideal of the nuclear family, not a problem of the institution itself or its setting in disadvantaged circumstances. The 'heaven' of family is already there, it is just that particular people are inadequate to enter it.

4.11 In this way tradition is idealised, and is used as a legitimating and positioning resource. However, in practice 'tradition' is often re-invented or reformed as people adapt and improvise. This is a form of bricolage in itself. Think of the re-invention of the white wedding, discussed earlier. The cultural display of a wedding, and the multiple performances that constitute it (as brides, grooms, flower girls, bride's father, guests, etc) are not just seen as meaningful by participants, who see the show as necessary for publically conveying the meaning of marriage and commitment (Carter 2010). This meaning also requires the 'symbolic aerosol' of tradition to cement its legitimation. I once attended an 'alternative' druid wedding, complete with performances from pagan priests from east, west, south and north. Even the alternative needs tradition. Similarly, I recently stayed in a Provencal hill village almost entirely populated by Belgian and British ex-pats. Nonetheless, the new village life still needed organisation (how to arrange yoga classes for example), and the easiest way seemed to be a re-enacting of pre-existing peasant feasts at important markers in the now defunct agricultural calendar. As Giddens wrote in 1984 (ironically given his later individualisation work), institutions so derived survive partly due to the moral command of what went before over the present.

4.12 This re-use and re-invention of tradition can lead to 'institutional leakage', as Douglas (1973) put it. Through adaption, meaning leaks from the older forms into new ones. Marriage, unmarried cohabitation, and living apart together (LAT) all are quite different legally; similarly, all contain within them the potential for quite different versions of intimacy and are sometimes experienced as such. However, in practice, people's lived lives are usually quite similar within all three couple forms (Barlow et al 2005, Duncan and Phillips 2008). This is because intimacy within them is partly maintained, rationalised and legitimated by ideas of romantic love and commitment 'leaking' from pre-existing ideas surrounding 'traditional' marriage. This is an empirical case of theorists confusing what agents can potentially do with what they actually do. In this way the so often theorised duality between traditional and (post/late) modern is misleading. Which is traditional (marriage?), which is modern (cohabitation / LAT)? The answer is neither, both are in–between as supposedly 'traditional' meanings leak into supposedly 'modern' practices. This leakage can be a two way process. Hence the supposed golden standard of marriage, when examined closely in terms of what partners do and expect, resembles a form of cohabitation in legal dressing (Lewis 2001). In this way Giddens was half correct in his 1994 assertion that 'the past is not preserved but continuously reconstructed on the basis of the present' (op cit, 63); the other half is however his 1984 observation that tradition survives through its moral claims over the present.

4.13 A key to bricolage is social legitimation. Not anything and everything goes. For bricolage is not just about adapting from existing practices to create something new, but about successful institutionalisation and social reproduction of this new practice over time. This means acceptance and validation by other people, not just individually but collectively. Successful bricolage will thereby involve negotiation and contestation. The assembly of parts and the adaption of tradition for a new purpose implies a conscious scrutiny of some tradition, of beliefs, norms, values and arrangements. People can be discursively critical of some parts of tradition even as they unconsciously accept others. So although claim on tradition is a legitimating device, tradition is not necessarily sacrosanct, nor automatically accepted by all actors. Weeks et al. (2001) on same-sex intimacies and the emergence of 'families of choice' give a good example. The research respondents actively created 'chosen' families, based around friendship rather than kin, partly as a means to confirm an alternative identity and a new way of belonging; in this way they discursively interrogated tradition and saw themselves as trying to do something different from conventional families. But at the same time, less critically and less consciously, they also sought legitimacy for these new arrangements through linking them with existing, traditional family images – all the more useful in this way because of their widespread, and generally uncritical, acceptance as entirely positive. Civil Partnership in Britain, through which same sex couples can legally register in quasi-marriage, epitomises this nexus of 'traditional and modern', and the combination of critical scrutiny with unconscious acceptance.

4.14 For Civil Partnership, while recognising and legitimating partnerships with alternative sexualities, almost totally reproduces the standard heterosexual marriage legally, ceremonially and symbolically. Hence the worry expressed by some that civil partnership institutionally de-radicalises and co-opts gay men and lesbians into heteronormative models of coupledom; they will be less inclined, and less able, to forge new and more progressive ways of developing relationships outside the traditional family. On the other hand, civil partners are now able to use their new legal status to 'naturalise' their love, care and commitment (Shipman and Smart 2007). Indeed, sometimes things are changed, at the discursive level, so that other things - left unremarked and accepted unconsciously - can remain the same (Crow 2008). Changes to divorce law, and the normalisation of divorce and separation, are good examples, for arguably these changes have allowed the 'traditional' institutions of marriage and weddings to survive. This combination of simultaneously questioning and using tradition will be socially uneven and will produce contestation and negotiation both within families and within institutions, as these examples show (see also Wilson 2007). At the same time bricoleurs are unequal in their resources, capacities, and institutional locations. As discussed earlier, some agents will be better able to develop new practices than others. By the same token some bricoleurs will be more able to influence the outcome, in terms of social acceptance, then others. The adapted development of practices will be all the more uneven. Not all potential bricolage is either possible or successful.

5. Conclusion

5.1 Individualisation theories misrepresent and romanticise agency as a primarily discursive and reflexive process where people freely create their personal lives in an open social world divorced from tradition. There may be constraints of various sorts on action, but these are external to an unbounded agency. But empirically we find that people usually make decisions about their personal lives pragmatically, bounded by and in connection with other people, not only relationally but also institutionally. This pragmatism is often non-reflexive, habitual and routinised, even unconscious. Agents consciously and unconsciously draw on existing traditions - styles of thinking, sanctioned social relationships, institutions, the presumptions of particular social groups and places, lived law and social norms - to 'patch' or 'piece together' responses to changing situations. Often it is institutions that 'do the thinking'. People try to both conserve social energy and seek social legitimation in this adaption process, a process which can lead to a 're-serving' of tradition even as institutional leakage transfers meanings from past to present, and vice versa. But this will always be socially contested and socially uneven. This process of bricolage is a basic reason for the lack of congruence between the way individualisation theory depicts contemporary personal life and people's lives as represented in empirical studies.5.2 This version of bricolage defines how people actually link structure and agency through their actions. It can provide a framework for empirical research in giving a range of operational questions to pursue. Rather than seeking for modern, individualising or traditional behaviour, we can instead ask how people adapt and re-serve tradition in reacting to new circumstances, how this may - or may not - secure legitimation, how meanings leak from older to newer traditions and, not least, in what ways these processes and their outcomes are socially uneven and unequal. In this way bricolage can provide a perspective for developing those current theorisations of family and personal life which are more in tune with contemporaneous empirical studies than individualisation theory. The ideas of 'doing' family practices, located in wider systems of meaning, and articulated through moral rationalities, relationality and 'proper' display (see James and Curtis 2010, Smart 2011 for recent accounts), empirically echo a wider bricolage perspective. For the common thread that runs through them is the idea of people doing family as they act pragmatically within their circumstances This echo also alerts us, however, to a relative neglect of the institutional and the unequal in this tradition of family studies (cf Heaphy 2011). Put together, this set of mid range theory confronts individualisation theory as an alternative theorisation of family and personal life. My argument here is that bricolage can provide an organising perspective.

Notes

1 The 'white wedding' first appeared among elite groups in the mid 19th century, supposedly after Queen Victoria chose white for her wedding to Prince Albert in 1840. Before this, wedding gowns were typically red or brown, even black. Etiquette books then began to turn the white gown into a tradition, and it became a symbol of status that also carried a connotation of innocence and sexual purity. Nonetheless, white weddings did not become common in the middle classes until the 1950s, and it was the 1980s that saw their final pervasiveness; ironically in view of the increasing likelihood of pre-marital sex and cohabitation.2 The classic wedding cake of a multi-tiered, rich and iced fruitcake seems to have emerged, like the white wedding with which it was intimately connected, in the late 19th century (following the example set by one of Queen Victoria's daughters in 1859). Earlier traditions used decorated loaves or oatcakes. It became especially popular in English speaking countries by the early 20th century, and has been especially tenacious in Britain where the rite of joint public cutting by bride and groom seems to represent the entrance of the couple into marriage as a different state.

3 Data were taken from British Social Attitudes 2006, Mass Observation's 'Little Kinsey' 1949 report, and Geoffrey Gorer's 1950 survey. See Duncan 2011 for details.

4 We presumably used the term 'rationality' because of the dominance of conventional economic explanations in the field at that time, either explicitly or implicitly (as in much of social policy); see Duncan and Edwards 1999, ch. 8.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Frances Cleaver and Sasha Roseneil for help and advice. Thanks also to the editors and the anonymous referees.

References

AHLBERG, J., Roman, C., Duncan, S. (2008) 'Actualising the 'democratic family'? Swedish policy rhetoric versus family practices' Social Politics, 15, 1, 1-22

BANYARD, K. (2010) The Equality Illusion: The Truth about Men and Women Today London, Faber.

BARLOW, A., Duncan, S. Grace, J. and Park, A. (2005) Cohabitation, Marriage and the Law: Social Change and Legal Reform in the 21st Century, Oxford: Hart.

BAUMAN, Z. (2003) Liquid love: on the frailty of human bonds Oxford: Polity.

BECK, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002) Individualisation, London, Sage.

BOURDIEU, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

CARTER, J. (2010) Why Marry? Young women talk about relationships, marriage and love. PhD thesis, University of York, <http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/1113/>

CHARSLEY, S. R. (1992) Wedding Cakes and Cultural History London, Routledge. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203404140]

CLEAVER F. (2002) 'Reinventing Institutions: Bricolage and the Social Embeddedness of Natural Resource Management' The European Journal of Development Research, 14, 2, 11-30.

CLEAVER, F (2011) Development as Bricolage London, Earthscan.

COLLET, F. (2009) 'Does habitus matter? A comparative review of Bourdieu's habitus and Simon's bounded rationality with some implications for economic sociology' Sociological Theory, 27, 4, 419-434. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01356.x]

CROW, G (2008) 'Thinking about families and communities over time' ch. 2 in Edwards, R. (ed) Researching Communities and Families, London, Routledge.

DOUGLAS, M (1973) Rules and Meanings, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

DOUGLAS, M. (1987) How Institutions Think, London, Routledge.

DUNCAN S. (2005) 'Mothering, Class and Rationality' Sociological Review, 2005, 53, 2, 49-76.

DUNCAN, S. (2011) 'The world we have made? Individualisation and personal life in the 1950s' Sociological Review, 9, 2, 242-265. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02001.x]

DUNCAN, S. Barlow, A., James, G. (2005) 'Why don't they marry? Cohabitation, the common law marriage myth, and commitment' Child and Family Law Quarterly, 17, 3, 383-398.

DUNCAN, S. and Edwards, R. (1999) Lone Mothers, Paid Work: and Gendered Moral Rationalities, London, Macmillan. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9780230509689]

DUNCAN, S., Edwards, R., Alldred P., Reynolds, T. (2003) 'Motherhood, paid work, and partnering: values and theories' Work, Employment and Society, 17, 2, 309-30. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0950017003017002005]

DUNCAN, S., Edwards, R., Alldred P., Reynolds, T. (2004) 'Mothers and childcare: policies, values and theories 'Children and Society, 18, 4, 245-65. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1002/chi.800]

DUNCAN, S. and Phillips, M. (2008) 'New families? Tradition and change in partnering and relationships' in Park, A., Curtice, J., Thomson, K., Phillips, M., Johnson, M. and Clery, E. (eds.) British Social Attitudes: the 24th Report, London: Sage.

DUNCAN, S. and Phillips, M. (2010) 'People who live apart together (LATs) - how different are they?' Sociological Review, 58, 1, 112-134. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2009.01874.x]

DUNCAN, S. and Smith, D. (2006)'Individualisation versus the geography of new families' 21st Century Society: the Academy of Social Sciences Journal 1, 2: 167–189.

GIDDENS, A. (1984) The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration, Polity Press, Cambridge.

GIDDENS, A. (1992) The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies Cambridge: Polity Press.

GIDDENS, A. (1994) 'Living in a post industrial society' in Beck, U., Giddens, A. and Lash, S. (eds.) Reflexive Modernisation: Politics, tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, Cambridge, Polity Press

GIDDENS, A (2000) 'Preface' to Hakim, C. (2000) Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, vii.

GROSS, N. (2005)' The detraditionalisation of intimacy reconsiderd' Sociological Theory, 23, 3, 286-311. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2751.2005.00255.x]

GUEST, T. (2004) My Life in Orange, Cambridge, Granta Books.

HAKIM, C. (2000) Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

HEAPHY, B. (2011) 'Critical Relational Displays' in Dermott, E. and Seymour, J. (eds) Displaying Families. London, Palgrave.

JAMES, A. and Curtis, P. (2010) 'Family displays and personal lives' Sociology, 44, 6, 1163-1180. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038510381612]

JAMIESON, L. (1998) Intimacy: Personal Relationships in Modern Societies Cambridge: Polity.

DE KONING, J (2010) 'Reshaping institutions. Bricolage processes in smallholder forestry in the Amazon' PhD thesis, University of Wageningen, The Netherlands.

LEVIN, I. (2004) ‘Living apart together: a new family form’ Current Sociology, 52,2, 223-40.

LEWIS, J. (2001) The End of Marriage? Individualism and Intimate Relationships Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

MCCULLOCH, A. (1982) 'Alternative households' in British Family Research Committee Families in Britain, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

MARX, K (1934) The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonapatre Moscow, Progress Publishers.

MARTIN, J. (2010) 'Life's a beach but you're an ant, and other unwelcome news for the sociology of culture' Poetics 38, 228–243

MASON, J. (2004) 'Personal narratives, relational selves: residential histories in the living and telling', Sociological Review, 52, 2, 162-179.

MORGAN, D. (1996) Family Connections, Cambridge: Polity.

ROSENEIL, S. (2006), 'The Ambivalences of Angel's 'Arrangement': a Psychosocial Lens on the Contemporary Condition of Personal Life', in The Sociological Review, 54(4), 847-869.

ROSENEIL, S. (2009) 'Haunting in an age of individualisation': subjectivity, relationality and the traces of the lives of others' European Societies, 11, 3, 411-30. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616690902764823]

SHIPMAN, B and Smart, C (2007) 'It's Made a Huge Difference': Recognition, Rights and the Personal Significance of Civil Partnership' Sociological Research Online, 12, 1.

SMART, C (2007) Personal Life: New Directions in Sociological Thinking Polity.

SMART C. (2011) 'Relationality and Socio-cultural Theories of Family Life' in R. Jallinoja and E. Widmer (eds) Families in the Making, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

SYLTEVIK, L. (2010) 'Sense and sensibility: cohabitation in "cohabitation land"' Sociological Review, 58, 3,444-462. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01932.x]

VOGLER, C. (2005) 'Cohabiting couples: rethinking money in the household at the beginning of the 21st century' Sociological Review 53,1, 1-29. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00501.x]

WACQUANT, L. (2005) "Habitus' in M. Zafirovski (ed) International Encyclopaedia of Economic Sociology, 315-19.

WALBY, S. (1986) Patriarchy at Work: patriarchal and capitalist relations in employment, Polity, Cambridge.

WALTERS, N. (2010) Living Dolls: the return of Sexism, London, Virago.

WEEKS, J., Heaphy, B. and Donavan, C. (2001) Same Sex Intimacies: Families of Choice and Other Life Experiments. London: Routledge. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203167168]

WENGRAF, T (2001) Qualitative research interviewing: biographic narrative and semi-structured method. London: Sage Publications.

WILSON, A. (2007) 'With friends like these: The liberalization of queer family policy' Critical Social Policy, 27: 50-76. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261018307072207]