Preconditions for Citizen Journalism: A Sociological Assessment

by Hayley Watson

University of Kent, SSPSSR

Sociological Research Online, 16 (3) 6

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/16/3/6.html>

10.5153/sro.2417

Received: 9 May 2011 Accepted: 24 Jul 2011 Published: 31 Aug 2011

Abstract

The rise of the citizen journalist and increased attention to this phenomenon requires a sociological assessment that seeks to develop an understanding of how citizen journalism has emerged in contemporary society. This article makes a distinction between two different subcategories of citizen journalism, that is independent and dependent citizen journalism. The purpose of this article is to present four preconditions for citizen journalism to emerge in contemporary society: advanced technology, an "active audience", a "lived" experience within digital culture, and an organisational change within the news media.

Keywords: Sociology of Web 2.0, Citizen Journalism, Social Media, Digital Culture, User Generated Content, Digital Technology, Active Audience

Introduction

1.1 Recent academic interest in citizen journalism invites the question as to what is distinctive about the public's involvement in the news process today. Citizen journalism involves the activities of members of the public in contributing to the production and distribution of news items in society. History suggests that the public have always been involved in the news process in one way or another, and Dan Gillmor (2006) argues that the personal journalism we are witnessing with citizen journalism can be traced back to the 19th Century. Gillmor discusses the early pamphleteers in the United States of America, who before the passage of the First Amendment, took risks to ensure a free press and published their own writings. He refers to Thomas Paine, who "inspired many with his powerful writings about rebellion, liberty and government in the late 18th century" (Gillmor 2006: 2). In England, journalism that involved the public can be dated back to the 17th Century (at least) when news in the form of pamphlets was banned by the Star Chamber in London in October 1632, newsbooks began to be circulated through informal networks such as coffee houses (McNair 1994). As noted by Habermas (1989), this informal network for the discussion and publication of news took place within the "public sphere",[1] a place where citizens could come together as one group to discuss, in an unrestricted manner, matters of general interest.1.2 The public have, then, been part of the news production process for centuries. For a long time sociologists have been interested in the functioning and the impact of the media in society, as indicated by Max Weber's "survey of the press", announced in 1910. The question of where the news comes from is a relevant sociological question. As indicated by Schudson (1989), over the years sociologists have made a great effort to understand the production of news. What/who influences the production of news in today's society is therefore a continuing area of consideration within sociology. In 2007 Beer and Burrows discussed the need of what they referred to as a "sociology of web 2.0". As identified by O'Reilly (2005) Web 2.0 refers to a supposedly second upgraded version of the web that is more open, collaborative, and participatory (Beer and Burrows, 2008). A "sociology of web 2.0" involved sociologists investigating the impact of web 2.0 on familiar sociological issues. One such issue is how we come to understand the construction of news in society and the impact of the public on the news production process. Accordingly, we must take steps to understand what about society today has led to the deeper immersion of the public in the news production and distribution process via acts of citizen journalism.

1.3 The term "citizen journalism" refers to the involvement of the public in the collection, production and distribution of news items. There is little consensus over what constitutes "citizen journalism". In "We Media: How audiences are shaping the future of news and information," Bowman and Willis (2003) argue that audience participation in the news process, via what they refer to as "participatory journalism" includes collecting, reporting, analysing and disseminating. They believe participatory journalism to involve very little editorial attention: additionally, they state that very little "formal journalism" takes place. In this way, Bowman and Willis state that participatory journalism is a bottom-up phenomenon, which originates from "simultaneous, distributed conversations" that can either gain popularity or gain very little attention from Internet audiences (Bowman and Willis 2003: 9). Nip (2006) argues that there are two types of journalism in which the public participate: citizen journalism and participatory journalism. For Nip (2006: 225), citizen journalism refers to those acts of journalism in which individuals are involved entirely in the practice of journalism. They are responsible for "gathering content, visioning, producing and publishing the news product". The term "participatory journalism", coined by mainstream journalists, relates to the practice of involving members of the public in mainstream acts of journalism. In this way members of the public are given the opportunity to express their views within the news-making process.

1.4 Others, such as Hermida and Thurman (2008) refer to the public's involvement in contributing news material to news organisations as "user generated content". The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) has gone so far as to create a "User Generated Content Hub", which is dedicated to handling audience contributions. Material submitted to the BBC by members of the public goes through a process of moderation (BBC Editorial Guidelines, 2011) therefore, not all material submitted will automatically be published.

1.5 Elsewhere, Jay Rosen (2008) emphasises the self-publication element of citizen journalism: "When the people formerly known as the audience employ the press tools they have in their possession to inform one another, that's citizen journalism". Furthermore, journalism professor Stuart Allan (2007: 3), who specialises in studying citizen journalism in relation to extreme events such as terrorism and disasters, identifies acts of citizen journalism as spontaneous acts by individuals, in which an individual takes up the role of "journalist", bearing witness to the occurrence of events.

1.6 With such a variety of terms being utilised, in this article I make a distinction between dependent and independent forms of citizen journalism. Dependent forms of citizen journalism are those acts that rely on news media broadcasters for publication, such as the BBC. Alternatively, independent citizen journalism consists of those acts that are conducted entirely by the citizen journalist without the assistance of news broadcasters, trusting his/her own systems of communication, such as web 2.0 platforms and/or blogs to publish their news. It is necessary to note, that blogs and social networking websites (web 2.0) are not solely used for citizen journalism activities, rather they are in many cases, free platforms on the web that individuals can utilise for communication, discussion and sharing purposes.

1.7 The purpose of this article is to present four preconditions for citizen journalism in contemporary society: advanced technology, an "active audience", a "lived" experience within digital culture, and an organisational change within the news media. These preconditions were identified via an investigation of understanding the basic necessities for "citizen journalism" which was brought about via a thorough review of academic texts related to citizen journalism as well as a review of incidents of citizen journalism (in relation to cases of terrorism).

Precondition 1: Advanced Technology

2.1 The first precondition for the emergence of citizen journalism in society is "advanced technology", in particular "digital technology". In what has been describes as "technological determinist" perspectives of online journalism, emphasis tend to focus their attention on change within newsrooms as being technologically driven. As argued by Miller (2011: 3), Wilson (1990) defines "technological determinism" as "suggesting that new technologies set the conditions for social change". Rather constructionist approaches such as those that will be highlighted in this article believe that changes within online journalism are a result of "complex interaction between professional, organisational, economic and social factors" (Paulussen and Ugille, 2008: 28). With a technological determinist perspective, as argued by Miller (2011: 3), implicit in their view of the role of technology, is that "technology is something separate and independent of society". This article, takes the perspective of the former attitude. It views technology as a means of communication. Whilst this section is predominantly concerned with identifying the importance of technology as an enabler for citizen journalism, it is necessary to note, that technology alone is not viewed as being solely responsible for the emergence of citizen journalism in society, and as will be established, other preconditions discussed are also required.2.2 Digital technology saturates contemporary society (Gere 2002), and has played an important role in the way in which news is constructed and produced in society[2]. In relation to the construction of news, developments in technology have previously pushed the news media away from print-based production in the form of newspapers, magazines and pamphlets, and forced the media into what Campbell and Park (2008) refer to as the "virtual age", which made mass consumption of the media feasible via television, radio and film. Today, the construction of news in society has once again been influenced by developments in technology: for Campbell and Park (2008), this means that we have now entered a new age that revolves around personal communication, or what Castells (2001) refers to as the "information society".

2.3 Developments in technology in the past have led to the expansion of news to global "mass" audiences on part of those professionally working in the news media industry. Now however, as a result of digital technology that enables personal communication, we are witnessing an expansion of the news that enables members of the public, not professionally trained in creating news, to participate in the production and distribution of news online.

2.4 A key innovation in technology that has led to growths in citizen journalism is access and use of the Internet. In the United Kingdom (UK) access to the Internet is widespread: the Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2010) provides vital information on Britain's use of the Internet. Figures from August 2010 suggest that 30.1 million (60%) adults in the UK accessed the Internet on a daily basis. This compares to figures from 2006, in which only 16.5 million (35%) adults accessed the Internet on a daily basis. Additionally, 19.2 million (73%) households in the UK now have an Internet connection: an increase of five million from 2006 (Office for National Statistics 2010). Further statistics from the ONS (2010: 13) suggest that online activities include (among others): sending and receiving emails (90%), reading or downloading online news, newspapers or magazines (51%), listening to radio or watching web television (45%), posting messages to chat sites, social networking sites and blogs (43%), and uploading self-created content to any website to be shared (38%). Amongst a host of other activities, people in Britain can be seen to utilise the Internet to access information and to connect with other Internet users.

2.5 With what appears to be a social habit that involves accessing and using the Internet on a daily basis, we must consider what online platforms people are able to access for communication purposes, primarily the use of blogs and social networking websites. The blogosphere is a key arena in which citizen journalists are able to self-publish their own version of news stories. For Cowling (2005), the weblog introduces a range of new technological functions for the production, management and consumption of news. This is similarly supported by Lasica (2003: 71), who argues that blogging allows for individuals to play an "active role" in the process of "collecting, reporting, sorting, analysing and disseminating news": a function that was once retained solely and "exclusively" by the news media. Whilst blogging may be a useful form of self-publication for the citizen journalist, it is necessary for us to consider exactly what a blog is, how popular the activity of blogging is, and why it is particularly useful for citizen journalism. Quiggin (2006) defines a blog as:

A blog is simply a personal webpage in a journal format, using software that automatically puts new entries ('posts') at the top of the page, and shifts old entries to archives after a specified time, or when the number of posts becomes too large for convenient scrolling. (Quiggin 2006: 482)A blog can therefore be considered as a form of personal, individual publication, created by ordinary citizens using software available on the Internet. Individuals create "posts" which are organised in terms of what they have written and published most recently. These blogs are then published and available to other Internet users worldwide.

2.6 A factor worthy of consideration in the use of the blogosphere is that users do not have to purchase blog pages to input their own content. Nor do individuals have to be aware of any particular programming language to compile and upload a blog post. Rather, users can upload and create their own blog via free blog hosting sites, such as Google's Blogger. The simplicity of creating and using a blog makes the practice of blogging much more practical for Internet users without the knowledge and finance to set up their own webpages and therefore, from a technological perspective, blogging serves as a useful form of personal communication.

2.7 There has been a significant increase in the number of blogs created and indeed, the number of blog posts that are published across the Internet. Let us consider, then, the size of the blogosphere today. Technorati (2008) suggests that 133 million blogs have been created since 2002. A total of 7.4 million blogs had been created in the 120 days prior to the survey; 1.5 million of these blogs had been posted in the seven days prior to the survey; 900,000 blogs posts had been posted in the 24 hours prior to the survey. The random sample of 1.2 million blogs from over 66 countries worldwide, suggesting that blogging is gaining prominence on a global stage. This was an English-speaking survey only; unfortunately the sample is therefore not representative of the global blogging population. However, whilst caution must be taken, at a period in time where blogging is greatly under-researched, this is the most "accurate" statistical data currently available.

2.8 A second platform for the self-publication of citizen journalism is the use of social networking websites. Beer and Burrows (2007) argue that this rise of participatory culture is a result of the development of Web 2.0. Simply put, Web 2.0 refers to the increase in applications on the Internet that allow for the public collaboration and the sharing of information. For Beer and Burrows this expansion of public involvement in Web 2.0 is largely linked to the development and global popularity of social networking sites such as Facebook, Flickr (a photo sharing site) and Twitter (a real-time, short messaging, a tweet may be considered a form of micro blogging and is comprised of no more than 140 characters and can be uploaded via instant messaging services, the World Wide Web and mobile phone technology). Boyd and Ellison (2007) define a social networking website as:

[W]eb-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. (Boyd and Ellison, 2007: 1).

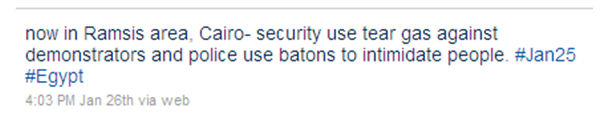

2.9 Social networking sites function as online platforms that individuals are able to sign up to and personalise, enabling global social interaction, sharing and communication in an online environment. Following the terror attacks in Mumbai in November 2008, global issues such as the 2009 swine flu epidemic , the 2009 protests in Iran[3], and the 2011 protests in Tunisia and Egypt have received a great deal of "publicity" by social networking sites, and have even been declared as promoting social movements. For example one activist used Twitter to report activities in the Ramsis area of Cairo:

|

| Figure 1. Ramy Raoof (2011) |

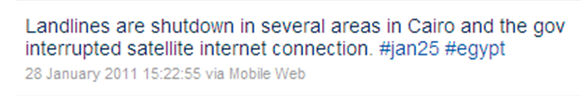

Protests in Egypt in January/February 2011 resulted in Egyptian authorities shutting off the Internet to stop protestors communicating with one another and from promoting news of the protests to the rest of the world. Ramy Raoof also used Twitter to tell people that landlines and Internet connections had been shutdown:

|

| Figure 2. Ramy Raoof (2011) |

2.10 As was revealed during the Egypt protests, the public's involvement in journalism surrounding an event is not necessarily restricted to participating in the media or writing on blogs. Therefore we must also consider the use of social networking websites such as Facebook and Twitter. A study by Global Web Index (2011) revealed that 47.1% of Internet users in the UK manage a social network profile (15.89 million users). The popularity of social networking sites is confirmed by other studies. A 2008 study by Ofcom revealed that in the UK 53% of adults has access to the Internet in their homes. Their study revealed that 39% of the population who have Internet access at home are signed up to a social networking website. This is larger than other European countries such as Italy (22%), France (17%) and Germany (12%) (Ofcom 2008: 21).

2.11 Developments in technology, such as blogs and social networking sites, are extremely important for citizen journalism. Adrian Monck argues that "new technology has enabled individuals to answer back, quickly and publicly" (Monck 2008: 23). For the most part, these developments have enabled individuals to communicate with one another on a global scale, without any specialist knowledge of Internet languages such as HTML, and are freely accessible for individuals to use so long as they have access to a computer or hand-held device (such as a smart phone) with a means of connecting to the Internet. However, technology alone is not responsible for the emergence of citizen journalism on the Internet – it is simply a means of capturing and publishing material. It is necessary to consider a second precondition for the emergence of citizen journalism, which is a desire on part of the audience to want to participate in the construction of the news.

Precondition 2: An Active and Engaged Audience

3.1 Members of the public have historically been conceptualised by some as "passive consumers" of the mass media. C. Wright Mills (1958) argued that the demise of the role of the public in American society was a consequence of this: rather than freely thinking and participating in the wider discussions surrounding civic life, members of the public were left to await and rely upon the appointment of a topic to discuss by the mass media. For Mills, in 1958, central organisations such as the mass media yielded a great social power - governing the public domain. In a review of audience studies, Webster (1998: 194) refers to mass-communication scholars regarding the audience as active "agents": thus, rather than seeing people as being mere consumers of the media, scholars within this field approach the study of the audience by asking the question "What do people do with the media?" Webster points to an observation by Bryant and Street (1988: 162) to support the idea of the "active" audience:The notion of the "active communicator" is rapidly achieving preeminent status in the communication discipline. In the mass and interpersonal literatures alike, we read statement after statement claiming that today's message receivers have abundant message options and actively select from and act on these messages. (Webster 1998: 195)

3.2 Proponents of the view of audiences as "agents" consider audiences to be able to formulate their own meaning of what they are exposed to. Some academics presenting this view are proponents of the "uses and gratifications model", where individuals' needs are the "driving force" behind consumption of the media (Webster 1998: 195). Katz, Blumler and Gurevitch (1974: 510) argue that the uses and gratification theory "represents an attempt to explain something of the way in which individuals use communications, among other resources in their environment, to satisfy their needs and to achieve their goals, and to do so by simply asking them". Accordingly, two studies of uses and gratification on the Internet can be cited here, where the authors used questionnaires to ask individuals why they used a particular form of media on the web.

3.3 Raacke and Bonds-Raacke (2008) conducted a study to understand the uses and gratification of two social networking websites: MySpace and Facebook. The study involved questionnaires, or what they refer to as a "packet", to be completed by 116 university students (Raacke and Bonds-Raacke, 2008: 170). Results suggest that uses and gratification of MySpace and Facebook range from keeping in touch with friends (96%) to using the sites for academic purposes (10.9%) (Raacke and Bonds-Raacke 2008: 171). The study also involved asking students why they felt others did not have an account on one of these websites. Explanations point to conscious decision-making on part of the individuals, such as: "They just have no desire to have an account" (70.3%), "they are too busy" (63.4%), "they think it is a waste of time" (60.4%), "they think it is stupid" (55.4%), "they have no Internet access at home" (51.5%), and "they are not good at using technology" (34.7%) (Raacke and Bonds-Raacke 2008: 171). A study by Kinally et al. (2008) similarly sought to identify the uses and gratification associated with the downloading of music, finding that this practice was a result of convenience and entertainment. Thus in both studies cited here, we see evidence of individuals actively utilising the Internet, and media on the Internet, for personal gratification.

3.4 Evidence of individuals actively engaging with the media force us to question what precisely it means to be "active". One approach is by considering activity as a form of interaction. Rafaeli (1988) defines interactivity as follows:

Interactivity is generally assumed to be a natural attribute of face-to-face conversation, but it has been proposed to occur in mediated communication settings as well. For example, interactivity is also one of the defining characteristics of two-way cable systems, electronic text systems, and some programming work, as in interactive video games. Interactivity is present in the operation of traditional media, too. The phenomenon of operation of letters to the editor, talk shows on radio and television, listener participation in programs and in programming are all characterised by interactivity. (Rafaeli 1988: 10)

3.5 In this view, communication online via blogs and social networking websites can be considered a valid form of interaction by individuals. Furthermore, Rafaeli comments on the importance of interactivity in society also occurring between the media and his/her audience: dependent citizen journalism can be considered an extension of this interactivity. A key point for our observation of the presence of the active audience is that Rafaeli and Sudweeks (1994: 3) go so far as to argue that interactivity is a form of social engagement that "merges speaking with listening". By posting information online, independent citizen journalists offer others the opportunity to engage with their material and interact with them if they choose to do so. The listening aspect of Rafaeli and Sudweeks' understanding of interactivity on the Internet, now also involves "reading".

3.6 In trying to understand whether or not audiences are active, Hermida et al. (2011) appear to have come to a crossroad in their decision. They argue that audiences are "active recipients" of news, which places them somewhere between being passive receivers and active creators of content:

"Users are expected to act when an event happens, by sending in eyewitness reports, photos and video. Once a professional has shepherded the information through the news production stages of filtering, processing and distributing the news, users are expected to react, adding their interpretation of the news. As "active recipients", audiences are framed as idea generators and observers of newsworthy events at the start of the journalistic process, and then in an interpretive role as commentators who reflect upon the material that has been produced". (Hermida et al., 2011: 17)

3.7 There is evidence of news consumers being more active in their search and consumption habits of the news. Audiences are utilising more than one source of news rather than relying upon a single news source: they are 'grazing' multiple news services (Rantanen 2009: 114). In the UK, Rantanen (2009: 115) cites that the proportion of individuals using the Internet as their main source of news has trebled to 6%. Similarly, Beckett (2008) believes that there has been a significant shift in audience behaviour – but here, Beckett focuses on differences in younger audiences and their consumption habits. He argues that younger audiences are utilising social websites to gain information regarding the news rather than relying on traditional sources such as newspapers and radio (Beckett 2008: 32). This relates to the growth in popularity of social networking websites such as Twitter and Facebook, but it may also be a result of what some have argued to be a significant difference in the way in which young people today have different "literacy" about technology than do older generations.

3.8 The Internet has played an important role in enabling audiences to be more "active" and has brought with it what Jenkins et al. (2006) refer to as a rise in "participatory culture", where individuals are not only involved in the consumption of culture online, but are taking part in the production of culture as well. The term "participation" invites the assumption that participation involves some form of activity. "Participation" has been defined by the Oxford English dictionary as "the action of taking part in an activity or event" (Soanes 2002: 610). In this case, "action" is required on part of the individual – this is not simply a given, but something that the individual must have some kind of desire to be motivated to involve him/herself in. Emphasis on the Internet as a force behind a move towards active audiences has also been supported by Clay Shirky (2000), who argues that the Internet in the twentieth century brought with it the decline of the "supposed" passive audience: for Shirky, we are now all "producers". Further still Rettberg (2008) argues that blogging is a fundamental part of the shift in communication in contemporary society. The public are participating in a new form of communication, resulting in a move from passive to active audiences:

Blogs are part of a fundamental shift in how we communicate. Just a few decades ago, our media culture was dominated by a small number of media producers who distributed their publications and broadcasts to large, relatively passive audiences. Today, newspapers and television stations have to adapt to a new reality, where ordinary people create media and share their creations online. We have moved from a culture dominated by mass media, using one-to-many communication, to one where participatory media, using many-to-many communication, is becoming the norm. (Rettberg 2008: 31)

3.9 This shift in communication is a result of the first precondition identified for citizen journalism: access to developed technology. Advanced technology, combined with an active audience, enables citizen journalism to occur online. Citizen journalism implies that audiences are interacting. Interaction may take place in many forms: with the news media, with other blogs and websites, and/or with other people. Downes and McMillian (2000: 174) argue that cyberspace offers "opportunities" for what they suggest are "new" forms of interactivity. They suggest that interaction that occurs online has a number of distinguishing features: "Communication is two way, timing of communication is flexible, the common communication environment creates a sense of place, participants have control over their communication experience, communication is responsive, and the purpose of the site seems to focus on information exchange" (Downes and McMillan 2000: 174). Take a social networking site such as Facebook as an example - it allows individuals to create their own space for communication and networking purposes. The individual has control over who can communicate with them, what they can share and, importantly, when they choose to interact. Prior to the Internet, the process of interactivity and communication was far more rigid and less unpredictable in terms of where/when interaction would take place.

3.10 This move from a passive to an active audience is a necessary precondition for citizen journalism to occur online. However, in order for citizen journalism to emerge, both precondition one (the utilisation of digital technology) and precondition two (an active and engaged audience) must come together online in what can be described as a third precondition for citizen journalism: a "lived" experience in digital culture.

Precondition 3: A "Lived" Experience in Digital Culture

4.1 In order for the public to participate in the practice of online citizen journalism, individuals must meet the precondition that they participate in digital culture, a "lived" experience of cyberspace. This article will employ the terms digital culture and cyberculture interchangeably to refer to the "lived" culture of cyberspace that lends itself to embracing online participation. Deuze (2006: 63) notes that a range of other terms are also used: information culture (Manovich 2001), interface culture (Johnson 1997), Internet culture (Castells 2001), virtual culture in cybersociety (Jones 1998).4.2 Cyberculture is a complex concept deriving from cultural studies, with no fixed definition. David Bell (2001) develops an understanding of the term by focusing on a number of key elements. First, he argues that the term cyberculture forces us to take note of what takes place when the terms "cyber" and "culture" are conjoined. Bell (2001: 2) argues that the term "cyberspace" implies a combination of three dimensions: material, symbolic and experiential. These dimensions are "material" in that cyberspace requires physical elements such as wires, machines, screens and so forth; "symbolic" in that cyberspace also exists in "images and ideas" - individuals do not simply have physical interaction with cyberspace but also see cyberspace employed in the media, for example through films such as The Matrix; and "experiential" in that we experience cyberspace in all its forms by "mediating the material and symbolic" (Bell 2001: 2). The second component of cyberculture is the notion of "culture". Bell argues that cyberspace is cultural as it is lived and "made by people", and thus is logically cultural. Bell (2001: 3) also argues that it is necessary to consider cyberspace as both "a product of and a producer of" culture.

4.3 Deuze (2006) argues that cyberculture is a feature of globalisation. Cyberculture is not restricted to the developed world, nor is it restricted by geographical boundaries: it is a global entity that stretches across space and time. Citizen journalism, a product of cyberculture, is also then a feature of globalisation. Cyberculture is driven, not solely by organisations that seek out amateur journalists, but also by the will of the individual. It takes effort on part of the individual to engage with events and make something out of them.

4.4 Deuze (2006) has developed three components of digital culture which provide a key way of understanding how a "lived" experience of digital culture can be used to respond to an event using citizen journalism. These three components are: participation, remediation and bricolage.

4.5 Participation allows for individuals to involve themselves actively in culture on the Internet. Relevant to this article is what Deuze (2006: 67) refers to as a "gradual increase" of audience participation with the news media. Deuze (2006: 68) describes this as a rise of "Do It Yourself" citizenship, in which individuals want to be heard and listened to rather than simply being spoken to. He argues that the Internet functions as an "amplifier" of participation and has created a culture of "participatory authorship" (Deuze 2006: 68). This amplification of participation can be seen in the audience's ability to participate with the news media, in terms of the submission of information by individuals and the subsequent publication of that "selected" information. It is necessary to point out that participation in cyberculture is not restricted to participating with the news media: members of the public are also able to utilise the Internet to participate independently from the news media in the production and distribution of information. Such arguments that emphasise the "good" behind participation online have been criticised. Keen (2007) argues that this rise in participatory culture is severely problematic: he argues that reliance on 'amateur' produced information simply implies that we are left with "the blind leading the blind" (Keen, 2007: 4).

4.6 Deuze's second component of cyberculture is "remediation". Remediation refers to the correction of information, whereby individuals are able to actively engage with old forms of media and critique its content by utilising new media. For Deuze, remediation is combined with "distantiation", which is:

…a manipulation of the dominant way of doing or understanding things in order to juxtapose, challenge, or even subvert the mainstream. In the context of my argument here it is important to critique the supposed deliberate nature of distantiation; what people do or expect from each other as they engage with digital media is primarily inspired by private interests, and not necessarily an expression of radical, alternative, critical, or activist sentiments. (Deuze, 2006: 68)In relation to citizen journalism, members of the public can access the Internet and new forms of media to challenge the mainstream media: this may not, as Deuze states, be a deliberate act, but rather a result of individuals engaging with digital media and responding to a given situation.

4.7 Relating to this is the third concept of digital culture – bricolage. Bricolage is defined as "the creation of objects with materials to hand, re-using existing artefacts and incorporating bits and pieces" (Deuze 2006: 70). The concept of bricolage is central to our understanding and future analysis of citizen journalism. Individuals refer to blogs to collate and publish information online. This information may not be first hand, but is a product of engagement with online sources by individuals. Deuze (2006: 71) argues that bricolage is an emergent practice and a distinctive feature of digital culture.

4.8 The precondition of a "lived" experience in cyberculture requires pre-condition one and two to be brought together, where both the availability and desire to utilise digital technology are essential if people are to participate in citizen journalism. However, whilst these three preconditions enable us to understand the emergence of a form of citizen journalism that is largely independent, one final precondition is necessary if we are to also understand the emergence of dependent forms of citizen journalism. This is an organisational change within the news media that enables dependent (online) citizen journalism to occur.

Precondition 4: Organisational Transition within the News Media

5.1 The fourth, and final, precondition for online citizen journalism is related directly to acts of dependent citizen journalism, by those who rely on the news media for publication. There must be a space for these individuals to publish their accounts within the presentation of the news by news media organisations on the Internet. Along with advances in technology, there have also been significant changes occurring within the functioning of the news media in society, in a process that can be described as an "organisational transition". Prior to outlining this organisational transition within the news media, which has enabled citizen journalism to emerge let us consider how news broadcasters have responded to advances in technology.5.2 The development of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s led to the growth in the use of the Internet as a news medium (Rantanen 2009: 116). For Adrian Monck (2008), the last decade (from 1999 onwards) has witnessed a "digital revolution" in which the media has come to dominate society. As previously discussed, forms of news media such as newspapers, magazines and radio have re-established themselves on the Internet, and in doing so have been able to increase their audience size. Furthermore, online news media organisations are able to expand the capacity and speed at which they are able to publish information. As a result, the Internet has allowed for a greater salience of news to be broadcast than ever before. Audiences are able to access vast amounts of material online at no cost.[4] Additionally, people are able to access material from a wide range of media: they are no longer restricted to local/national news, but can access a global forum of news via the Internet.

5.3 For Stuart Allan (2009: 15), the Oklahoma City Bombing on the 19th April 1995 represented the "tipping point", where online news organisations realised the potential for news sites to publish breaking news. The use of the Internet as a forum for the communication of news was underway by the mid 1990s (Rantanen 2009). Rantanen (2009: 116) argues that it is necessary to note that the Internet is not a news producer; rather it is a "vehicle for news" allowing for the transmission and reception of news. Rantanen points to Best et al. (2005), who argue that traditional media such as newspapers were quick to utilise the Internet. For example, by 2001 consumers could access approximately more than 15,000 newspapers from outside the US online. This was also met with the desire to access media online by audiences: the World Association of Newspapers argued that the Internet's audience for online newspapers has increased by 350% in recent years (Rantanen 2009: 117).

5.4 It is evident that the use of the Internet by both audiences and news media organisations has been quickly accepted as a forum for the communication of the news. Allan (2006) points to Katz (1997), who argues that the news media had to take note of the potential and capabilities that the new media had to offer: in particular, the new media's ability to stop the stagnation of news through using the Internet to publicise up-to-date "breaking"' news:

Newspapers have clung beyond all reason to a pretence that they are still in the breaking news business they dominated for so long, even though most breaking stories are seen live on TV or mentioned online hours, sometimes days, before they appear on newspaper front pages. (Katz 1997, in Allan 2006: 24)The realisation of the potential for enhancing the distribution of news forced a key organisational transition to occur within the news industry, and it is this transition that is a necessary precondition for acts of dependant citizen journalism.

5.5 The concept of "organisational transition" was developed by Richard Beckhard and Reuben Harris in 1987, and is useful way of identifying the possible reasons for changes within the operation of news organisations in society. They define organisations as "social systems", and state that "a social system is one in which the subsystems each have their own identities and purposes, but their activities must be coordinated or the parent system cannot function" (Beckhard and Harris 1987: 24).

5.6 Within the wide range of news organisations in society, each individual system has its own identity which editors and journalists strive to maintain. For example, The Daily Star, a tabloid newspaper in the UK, maintains its efforts to report on news, celebrities and sport, whereas a broadsheet newspaper such as The Financial Times, focuses on supplying international business, financial, economic and political news. Change within the news media today is noticeable. As identified by Beckhard and Harris (1987: 30), change within organisations is often instigated "outside" the organisation:

Changes in legislation, market demand resulting from worldwide competition, availability of resources, development of new technology, and social priorities frequently necessitate that organization managers redesign the organizational structures and procedures, redefine their priorities, and redeploy their resources. (Beckhard and Harris, 1987: 30)In terms of the news media, new technologies such as the Internet have forced competition within the news industry, with greater numbers of people spending their time online. It was only a matter of time before news agencies began to establish an online presence.

5.7 As identified by Gere (2002), the majority of media can be seen to have converged online by establishing themselves and participating in the production, publication and distribution of media on the World Wide Web. When an organisation changes the way it operates, in essence it changes not only the way in which it chooses to conduct business, but also the "culture" of an organisation. Beckhard and Harris (1987: 7) state that culture "is the set of artefacts, beliefs, values, norms, and ground rules that defines and significantly influences how the organisation operates". For example, by recognising the desire of some within the audience to participate in the discussion of news, news organisations also have to change how they perceive that interaction takes place: for example, by adopting strategies that allow news organisations to dedicate space for the public to "have their say". News organisations have indeed changed, largely as a result of advances in technology that have enabled them to adopt an online presence, which in turn has allowed for greater audience interaction with the news – a key precondition for dependent citizen journalism.

5.8 An example of a media organisation realising the importance of changing to meet the demands of publishing citizen journalist's material is provided by the BBC:

But for Newsgathering, what happened on 7 July three years ago marked a watershed: the point at which the BBC knew that newsgathering had changed forever. In one sense it was just an example of what might be called "accidental journalism". No one who set off for work that fateful morning had any idea that their mobile phones would capture such dramatic images…Within 24 hours, the BBC had received 1,000 stills and videos, 3,000 texts and 20,000 e-mails. What an incredible resource. Twenty-four hour television was sustained as never before by contributions from the audience; one piece on the Six O'clock News was produced entirely from pieces of user-generated content. At the BBC, we knew then that we had to change. We would need to review our ability to ingest this kind of material and our editorial policies to take account of these new forms of output. (Boaden 2008)

5.9 A distinctive feature of the news media operating on the Internet today is the use of social media tools such as blogs and social networking websites. A study conducted by Singer in 2004 revealed that professional news agencies, including television networks and other national news outlets, were creating blogs as part of their communication strategy. Singer points out that the first use of a blog to break a national news story was in 1998, in which the Charlotte Observer reported the unfolding events of Hurricane Bonnie (Singer 2005: 176). In the US, Stinger reports that according to the American Press Institute, over 400 blogs were owned and published by journalists, suggesting the acceptance and utilisation of the blogosphere within the mainstream media (Singer 2005: 176). Rantanen (2009) argues that in the US in March 2007, 95% of the top 100 newspapers included blogs from reporters: this figure had increased by 80% since 2006. Evidence suggests that in the US, the news media continue to incorporate the use of new forms for media such as blogs into their production and presentation of the news.

5.10 If news media organisations are using social media tools to present the news, it is also of interest to identify how organisations responded to the emergence of citizen journalists' desire to publish their information through the news media. A host of studies have sought to understand the integration of the audience into the news production process by news organisations (Domingo et al., 2008; Paulussen and Ugille, 2008; Singer, 2006; Singer and Ashman, 2009; Boczkowski, 2010). A recent British study by Hermida and Thurman (2008) reveals how British news organisations responded to the rise of what they refer to as "user-generated content". The study was conducted in November 2006 with the use of an online survey and in-depth interviews, and was a follow-up study to Thurman's research in 2005. Their sample consisted of twelve leading national newspapers (Hermida and Thurman 2008: 344). Results suggest that there exist nine formats to encourage audience participation: polls, message boards, have your say, comments on stories, Q&A's (Question and Answers), blogs, reader blogs, your media and your story. Of the twelve newspapers assessed, only one – The Independent - did not have a space that allowed audiences to participate in the wider discussion of news. Three of the newspaper websites sampled – The Guardian, The Sun and The Scotsman - forced audiences to register if they wanted to participate. It is therefore possible to note that as of 2006, not all (mainstream) newspaper websites in the UK encouraged audience participation.

5.11 In addition to surveying the nature of space available for audiences to interact with the news media, Hermida and Thurman (2008) also took efforts to conduct semi-structured interviews with news executives to try to understand the impact of the presence of the public on their presentation of the news. Results suggested that news executives were concerned about a number of "potential" consequences of the increase in user-generated content. Examples included fear of marginalisation by user media, and concern over retaining staff: for many this led to professional journalists being given "space" for their own blogs, so as to allow them to "target a different audience". As a news executive from The Mirror stated: "Our science editor is keen to take a blog because he can address an audience in a way which he feels more comfortable with rather than having to dress everything up as a tabloid idea" (Hermida and Thurman 2008: 349). A further explanation as to why news organisations may have felt reluctant to encourage audiences to interact with their newspapers and therefore may have been "struggling" to know how to allow user-generated content may be their desire to "protect the brand", and not wanting their identity to change as a result of what audiences might "say". In this way, news media organisations are forced to remain as "gatekeepers" by maintaining editorial control over the submission of comments. This suggests, as previously mentioned, that within the process of organisational change, the "culture" of news organisations has also had to be reconsidered, so as to incorporate the audience, whilst maintaining control over the identity of the news organisation as well as the content and quality of news.

5.12 The presence of "spaces" for members of the public to have a voice in news organisations is a central precondition for dependent forms of citizen journalism. The transition of the news media to online presentations of the news, and creating space for the public to participate in the construction of news, can be considered a sign that the media landscape is adhering to the demand for audience interaction. In effect this allows for the bridging between new forms of social media and traditional media organisations, presenting society with an ever-expanding interactive news media.

Citizen Journalism – Not New, Just Distinctive

6.1 It is evident that the public's involvement in the news process is not an entirely new form of journalism. However, in present society, via citizen journalism or by acting as what Bruns (2008) calls "produsers", members of the public are able to participate in both the production and usage of news in two distinct ways: through the self-publication of news online and via the publication of their material through the professional news media. Technology combined with a desire to participate enables individuals to interact with others in a digital culture that allows individuals to participate in forms of independent citizen journalism, where they use their own systems of communication to post their accounts of the news for audiences to view.6.2 Whilst the public's involvement in the journalism process is not new, the emergence of citizen journalism online is in part, a technology-driven mass phenomenon. Without the Internet and a public that is interested in sharing their experiences and accounts, forms of online citizen journalism would not be possible. In terms of its impact on society, the Internet allows for a potentially vast array of information to be communicated to audiences from a variety of perspectives, it enables the audience to be involved in the news production process – but only if the audience chooses to take part. However, we must take efforts to question what this means for society.

6.3 Some, such as Pamela Welsh (2007), a journalist writing for The Guardian, raised the issues of citizen danger. Following the Glasgow Airport attacks in 2007, Welsh was concerned about whether individuals would place themselves in danger by trying to record evidence, and ignore their civic duty of being of assistance to others. Elsewhere, Bakker and Paterson (2011) bring attention to whether or not citizen journalism may be seen as a form of anti-social behaviour. Glaser (2005) went so far as to call citizen journalism activities following the 7th July 2005 London bombings as "citizen paparazzi". Youngs (2009) questions what citizen journalism means for "trust", where audiences may be unpredictable which could result in unclear communication. These questions are valid, and require further sociological analysis of what citizen journalism means for society.

Notes

1A number of academics have pointed to the Internet being a "new" public sphere, going so far as to say that it is an international public sphere (Dakroury and Birdsall 2008). Elsewhere, Youngs (2009) has argued that there is a blurring between the private and public sphere on the Internet.2Within sociology, news in society has been referred to as a construction process, stemming from the work of Berger and Luckmann (1966), many sociologists such as Gieber (1964), Schlesinger (1978), Golding and Elliott (1979), Tuchmann (1980) and Schudson (1986) have made efforts to identify how the news is constructed.

3Update: It has since been noted by Golnaz Esfandiarin (2000), writing for Foreign Policy magazine, that the protests that occurred in Iran in June 2009 were not so readily co-ordinated by Twitter users in Iran as was first thought, but instead were fuelled by Twitter users outside of Iran. Whilst the use of Twitter did serve to heighten awareness of the protests, the degree to which it was used as a means of organising a social movement is currently being debated.

4Until recently, with media organisations such as Rupert Murdoch's The Times charging for audience access to online content. Charging audiences to view online content is not taking place within all media organisations, but rather is at what could be described as a trial phase (as of 14th July 2010). Recent figures from the Times suggest that forcing individuals to pay for online news has not been an obvious success. As of the 20th July 2010, audience statistics state that 15,000 people have paid for subscriptions to the Times, with the Times seeing a 90% reduction in audience figures. (http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2010/jul/20/times-paywall-readership).

References

ALLAN, S. (2006). Online News. Berkshire: Open University Press.ALLAN, S. (2007). Citizen Journalism and the Rise of 'Mass Self-Communication'. Global Media Journal Australian Edition, 1 (1): 1-20.

ALLAN, S. (2009). Histories of Citizen Journalism. In: Allan, S., and Thorson, E. Citizen Journalism Global Perspectives. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Corporation Ltd.

BAKKER, T., and Paterson, C. (2011). The New Frontiers of Journalism: Citizen Participation in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. In Brants, K., and Voltmer, K. Political Communication in Postmodern Democracy: Challenging the Primacy of Ethics. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

BBC EDITORIAL GUIDELINES. (2011). Section 17: Interacting with our audiences: Phone-In Programmes, User Generated Content Online, Mobile Content, Games and Interactive TV. BBC <http://www.bbc.co.uk/guidelines/editorialguidelines/page/guidelines-interacting-phone-in/#moderation> (21 June 2011).

BECKETT, C. (2008). Super Media: Saving Journalism So It Can Save The World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

BECKHARD, R., & Harris, R. (1987). Organizational Transitions: managing complex change. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Publishing Corporation.

BEER, D. & Burrows, R. (2008). Sociology and, of and in Web 2.0: Some Initial Considerations. Sociological Research Online, 12(5) <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/17.html> (14 April 2011).

BELL, D. (2001). An Introduction to Cybercultures. London: Routledge.

BERGER, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Doubleday.

BOADEN, H., (2008). The role of citizen journalism in modern democracy. BBC. <http://www.BBC.co.uk/blogs/theeditors/2008/11/the_role_of_citizen_journalism.html> (28 May 2010).

BOCZKOWSKI, P.J. (2010). News at Work. London: The University of Chicago Press.

BOYD, D. & Ellison, N.B. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Michigan State University.

BOWMAN, S. and Willis, C. (2003). We Media: How audiences are sharing the future of news and information. The Media Center at the American Press Institute.

BRUNS, A. (2008). The Active Audience: Transforming Journalism from Gatekeeping to Gatewatching. In Paterson, C. And D, Domingo. (2008). Making Online News: The Ethnography of New Media Production. New York: Peter Lang.

CAMPBELL, S.W. & Park, Y.J. (2008). Social Implications of Mobile Telephony: The Rise of Personal Communication Society. Sociology Compass, 2(2): 371-87.

CASTELLS, M. (2001). The Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, Business and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

COWLING, J. (2005). Digital News: Genie's Lamp or Pandora's Box? Digital Manifesto Project. <http://www.ippr.org/uploadedFiles/research/projects/Digital_Society/news_and_info_jcowling.pdf> (13 July 2010).

DAKROURY, A.I., & Birdsall, W.F. (2008). Blogs and the right to communicate: Towards creating a space-less public sphere. Technology and Society, IEEE International Symposium.

DEUZE, M. (2006). Participation, Remediation, Bricolage: Considering Principal Components of a Digital Culture. The Information Society, 22: 63-75. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01972240600567170]

DOMINGO, D., et al. (2008). Participatory Journalism Practices in the Media and Beyond. Journalism Practice, 2 (3): 326-342. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17512780802281065]

DOWNES, E.J. & McMillan, S.J. (2000). Defining Interactivity: A Qualitative Identification of Key Dimensions. New Media and Society, 2(2): 157-79. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/14614440022225751]

ESFANDIARIN, G. (2010). The Twitter Devolution. Foreign Policy Magazine. <http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/06/07/the_Twitter_revolution_that_wasnt?print=yes&hidecomments=yes&page=full> (30 November 2010).

GERE, C. (2002). Digital Culture. London: Reaktion Books.

GIEBER, W. (1964). News is What Newspapermen Make It. In L. A. Dexter, and D. M. White, People, Society and Mass Communication. London: The Free Press.

GILLMOR, D. (2006). We the Media: Grassroots Journalism By the People, for the People. Sebastopol: O'Reilly.

GLASER, M. (2005). Did London Bombings turn citizen journalists into citizen paparazzi? [Online]. The Online Journalism Review. <http://www.ojr.org/ojr/stories/050712glaser/> ( 23 June 2011)].

GLOBAL WEB INDEX. (2011). Global Web Index: Data <http://globalwebindex.net/data/> (14 February 2011).

GOLDING, P. & Elliott, P. (1979). Making the News. London: Longman.

HABERMAS, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge: Polity.

HERMIDA, A. & Thurman, N. (2008). A Clash of Cultures: The integration of user-generated content within professional journalistic frameworks at British newspaper websites. Journalism Practice, 2 (3): 343-356. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17512780802054538]

HERMIDA, A., et al. (2011). The Active Recipient: Participatory Journalism through the lens of the Dewey-Lippmann Debate. International Symposium on Online Journalism 2011: Austin, Texas. [Online]. Available from: <http://online.journalism.utexas.edu/2011/papers/Hermida2011.pdf> [Accessed 5 July 2011].

JENKINS, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robison, A.J., & Weigel, M. (2006). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. MacArthur Foundation.

KATZ, J.E., Blumler, JG., & Gurevitch, J. (1974). Uses and Gratifications Research. American Association for Public Opinion Research, 37, (4): 509-523.

KEEN, A. (2007). The Cult of the Amateur. London : Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

KINNALLY, W., Lacayo, A., McClung, S. & Sapolsy, B. (2008). Getting up on the download: college students' motivations for acquiring music via the web. New Media and Society, 10, (6): 893-913. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444808096250]

LASICA, J. D. (2003, August). What is Participatory Journalism? Online Journalism Review. <http://www.ojr.org/ojr/workplace/1060217106.php> (10 September 2010).

MCNAIR, B. (1994). News and Journalism in the UK: A Textbook, London: Routledge.

MILLER, V. (2011). Understanding Digital Culture. London: Sage Publications.

MILLS, C.W. (1958). The Structure of Power in American Society. The British Journal of Sociology, 9(1): 29-41. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.2307/587620]

MONCK, A. (2008). Can You Trust The Media? London: Icon Books.

NIP, J. (2006). Exploring the Second Phase of Public Journalism. Journalism Studies, 7 (2): 212-236. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616700500533528]

OFCOM. (2008). Social Networking: A quantitative and qualitative research report into attitudes, behaviour and use. <http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/media-literacy/report1.pdf> (4 April 2011).

OFFICE FOR NATIONAL STATISTICS, (2010). Statistical Bulletin: Internet Access 2010. <http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/iahi0810.pdf> (4 November 2010).

PAULUSSEN, S., and UGILLE, P. (2008). User Generated Content in the Newsroom: Professional and Organisations Constraints on Participatory Journalism. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 5 (2): 24-41.

QUIGGIN, J. (2006). Blogs, wikis and creative innovation. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(4): 481-96. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1367877906069897]

RAFAELI, S. (1988). Interactivity: From new media to communication. <http://gsb.haifa.ac.il/~sheizaf/interactivity/> (10 March 2011).

RAFAELI, S. & Sudweeks, F. (1994). Interactivity on the Nets. Paper Presented at Information Systems and Human Communication Technology Divisions Annual Conference, Sydney, Australia.

RANTANEN, T. (2009). When News Was New. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781444310870]

RAOOF, R. (2011). Twitter Page: Rammy Raoof <http://twitter.com/RamyRaoof#> (14 February 2011).

RETTBERG, J.W. (2008). Blogging. Cambridge: Polity Press.

ROSEN, J. (2008, July 14). A Most Useful Definition of Citizen Journalism. Press Think. <http://journalism.nyu.edu/pubzone/weblogs/pressthink/2008/07/14/a_most_useful_d.html#more> (Accessed 12 August 2009).

SCHLESINGER, P. (1978). Putting 'reality' together: BBC News. London: Constable.

SCHUDSON, M. (1989). The Sociology of News Production. Media, Culture and Society, 11: 263-282. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/016344389011003002]

SHIRKY, C. (2000). RIP The Consumer, 1900-1999. <http://www.shirky.com/writings/consumer.html> (Accessed 26 April 2010).

SINGER, J. B. (2005). The political j-blogger: 'Normalizing' a New Media Form to Old Norms and Practices. Journalism , 6 (2): 173-198.

SINGER, J.B. (2006). Stepping Back from the Gate: Online Newspaper Editors and the Co-Production of Content in Campaign 2004. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 83 (2): 265-280.

SINGER, J.B. and ASHMAN, I. (2009). '"Comment Is Free, but Facts Are Sacred": User-generated Content and Ethical Constructs at the Guardian'. Journal of Mass Media Ethics 24: 3–21. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08900520802644345]

SOANES, C. (2002). Paperback Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

TECHNORATI, (2008). State of the Blogosphere. <http://technorati.com/blogging/state-of-the-blogosphere//> (15 May 2009).

TECHNORATI MEDIA, (2009). About. <http://technoratimedia.com/> (18 May 2009).

TUCHMAN, G. (1980). Making News: A Study in the Social Construction of Reality. London: Collier Macmillan Press.

WEBER, M. (1998). Preliminary report on a proposed survey for a sociology of the press. History of Human Sciences, 11 (2): 111-120. [doi:://dx.doi.org/10.1177/095269519801100207]

WEBSTER, J.G. (1998). The Audience. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 42, (2): 190-207.

WELSH, P. (2007). Disaster Movies [Online]. The Guardian. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2007/jul/02/disastermovies> (10 September 2010).

YOUNGS, G. (2009). Blogging and Globalization: the blurring of the public/private spheres. Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives, 61(2): 127-38.