Under the Influence? The Construction of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome in UK Newspapers

by Pam Lowe, Ellie Lee and Liz Yardley

Aston University; University of Kent at Canterbury; Aston University

Sociological Research Online, 15 (4) 2

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/15/4/2.html>

10.5153/sro.2225

Received: 4 May 2010 Accepted: 10 Sep 2010 Published: 30 Nov 2010

Abstract

Today, alongside many other proscriptions, women are expected to abstain or at least limit their alcohol consumption during pregnancy. This advice is reinforced through warning labels on bottles and cans of alcoholic drinks. In most (but not all) official policies, this is linked to a risk of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) or one of its associated conditions. However, given that there is little medical evidence that low levels of alcohol consumption have an adverse impact on the foetus, we need to examine broader societal ideas to explain why this has now become a policy concern. This paper presents a quantitative and qualitative assessment of analysis of the media in this context. By analysing the frames over time, this paper will trace the emergence of concerns about alcohol consumption during pregnancy. It will argue that contemporary concerns about FAS are framed around a number of pre-existing discourses including alcohol consumption as a social problem, heightened concerns about children at risk and shifts in ideas about the responsibility of motherhood including during the pre-conception and pregnancy periods. Whilst the newspapers regularly carried critiques of the abstinence position now advocated, these challenges focused did little to refute current parenting cultures.

Keywords: Foetal Alcohol Syndrome, Parenting Cultures, Media, UK

Introduction

1.1 Today, alongside many other proscriptions, pregnant women are expected to abstain from, or at least limit, their alcohol consumption. Indeed, the government advice booklet Pregnancy and Alcohol (Dept of Health 2008) suggests that abstinence should begin prior to conception and continue through breastfeeding into mothering in general. This advice is reinforced through warning labels on alcoholic drinks. In most (but not all) official policies, this is linked to a risk of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) or one of its associated conditions within the broader label of Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) (e.g. DH 2008, 2009). Drawing on British newspapers, this paper traces one of the ways that cultural understandings of FASD are linked to broader ideas about motherhood. It illustrates how the expansion and development of concerns about drinking and pregnancy can be associated with shifts in broader discourses rather than changes in scientific knowledge. We also show how, although these discourses are not accepted uncritically in newspapers, the challenges that are presented by journalists often reinforce rather than refute current parenting cultures.

Health concerns and the media

2.1 As Seale (2002) has argued health stories are a staple element in media coverage, both in news and lifestyle reporting. To be considered newsworthy, like other stories, health reports need to be recent, factual, relevant to their readership, and have resonance with templates or stereotypes already established within current discourses. In addition, journalists may seek to achieve 'balance' in stories, by reporting different sides of a story, although the emphasis and prominence of particular viewpoints can often undermine this in practice (Boyce 2007). The relationship between the producers, media narratives, and audience is complex. In terms of production, journalists are often pushed for time and may lack understanding of scientific terminology or epidemiological understanding of risk (Larsson et al 2003, Wilson et al 2004). Consequently, they often rely on a small number of 'experts' that have previously proved to be readily available and are willing to distil the message in a convenient form (Hodgetts et al 2007). Narratives in the media often utilise particular forms which can include oppositional forces such as victims and villains, heroic deeds and hidden dangers. Yet as Seale points out, these elements do not have to be included in all stories as the audience can 'fill in the gaps' (2002:30).2.2 As well as standard media reporting elements, Seale highlights a number of issues in health reporting that are of particular relevance to research about the media and FASD. These include the threat to 'innocent children' and the roles of 'ordinary heroes' and 'moral entrepreneurs' (Seale 2002). Seale (2002) also highlights that stories of unexpected dangers from ordinary objects and activities are regularly covered by news reports. Of particular relevance here are the ways in which pleasurable activities have been constructed as a potential risk, for example through sex and food scares.

2.3 Whilst it is clear that health stories can impact on health related behaviour, this is neither certain nor predicable. Audiences may compare the story to their own understanding of the issue and respond accordingly. Miller (2007) found that media reports warning users to stay away from potential 'killer batches' of heroin were rejected by some users as an unlikely risk, whilst others specifically sought to find the 'killer batch' assuming it would be purer and increase the pleasure of consumption. In another example, Boyce's (2007) study of the MMR vaccination scare found that the coverage had a significant impact on parents. Whilst only a minority of parents refused to have their children immunised with the MMR vaccine, many more worried about its safety and sought additional advice about the vaccine. Consequently, whist media framing is an important element in the story of FASD in the UK, further work needs to be done to explore how the messages are received, and the relation between this and perceptions of risk and behaviour.

Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

3.1 As Armstrong (2003) has argued FAS was 'discovered' in 1970s when a paper was published outlining a particular pattern of congenital anomalies in the children of alcoholic mothers (Jones et al, 1973). Foetal Alcohol Syndrome is now internationally recognised although there is still some variation in diagnostic criteria between countries (BMA 2007), and FAS is considered difficult to diagnose as the clinical indicators such as particular facial features are similar to other conditions and can change over time (BMA 2007). Exact knowledge of maternal alcohol consumption can be absent (for example in the case of adoption) or deemed to be unreliable (such information obtained from mothers self-reports). As women addicted to alcohol also tend to have poor diets and may smoke, the exact cause of abnormal foetal development may be difficult to pinpoint (Armstrong 2003). If the clinical indicators for FAS are not met, but the clinician believes that congenital anomalies or developmental issues are linked to the mother's consumption of alcohol, there is a range of other diagnoses that can be made such as Alcohol-Related Birth Defects. These are grouped together using the umbrella term FASD. There are no accurate statistics for the numbers of children with FASD in the UK. In England, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) indicate that between 1996 and 2005 there were less than 350 finished consultant episodes per year where there was an alcohol-related diagnosis of a newborn or foetus (HESonline accessed 24/06/09). However, as HES point out diagnosis is more likely to occur in primary care rather than in hospital (accessed 24/06/09). The DH (2007a) and HES (2009) rely on estimates from FAS pressure groups and campaigning organisations such as NOFAS[1] in estimating that between 6,000 and 7,000 babies each year are born affected by FASD despite the lack of evidence provided by the organisations to support such claims[2].3.2 Golden's (2005) analysis of US television coverage of FAS shows it went through several phases. Initially, FAS was set in the wider discourse of alcoholism as a disease, and children affected were construed to be the unintended 'victims' of their mother's illness. Over time, the discourse shifted to one of maternal deviance, and the issue was more firmly associated with women from poor and/or minority-ethnic communities. At that time, there was also a 'moral panic' about crack-addicted babies which, Golden (2005) argues, helped to modify discussions of FAS into stories about crime and disorder. These elements were also reflected in some newspaper reporting.

3.3 In their study of FASD in regional newspapers in the northeast US, Connolly-Ahern and Broadway (2008) found three main frames of coverage, 'dangerous mothers', 'fetal wellness', and 'victimization'. Their first frame 'dangerous mothers' ranged from stories about women charged with child abuse because of their alcohol consumption during pregnancy through to stories that women who consumed any alcohol during pregnancy were irresponsible and therefore potentially unfit to parent. The frame of 'fetal wellness' included reporting about advice to women on how to avoid placing the foetus at risk. Here the dominant message was that alcohol abstinence was best, but could also include reassurance that a small amount of alcohol was probably not a problem. Connolly-Ahern and Broadway (2008) reported that this frame contained most of the expert sources, such as official advice and medical opinions, but that rather than particular sources emerging as key experts, the sources were varied. The final frame of 'victimization' included the stories of those diagnosed or reported to have FASD, but also their carers, as many such people were fostered or adopted. However, those said to have FASD could lose their victim status if they were reported to have committed violent crimes or dangerous activities. Where others were hurt or killed in the incident, they would become the victim. Connolly-Ahern and Broadway (2008) argue that overall the coverage in the newspapers they looked at focused on mothers as a potential risk to their children rather than drawing out the complexities of the issues. In this respect, the coverage can be described as moralized and moralizing, as stories tended to centre on the need for rational individualised harm avoidance by women (Hier 2008).

Moralization and parenting cultures

4.1 As Hier (2008) has argued, in contemporary societies moralization can be understood as a key feature of media discourses. Discourses emerge which highlight moral transgressions of individuals and groups which are deemed potentially harmful to wider society. Such discourses often emphasise the need for individualised self-control, but may also include discussion of societal responses to the perceived risk (Hier 2008). Whereas 'moral panics' need an identifiable 'folk devil' that is credited with causing harm, understanding media discourses as moralization allows exploration of them as less certain and more routine (Hier 2008). Critcher (2009) argues that moralization is part of a continuum of moral regulations of which moral panics can be a part. He suggests that to understand different dimensions of moral regulation we need to analyse discourses through three concepts. The first is the threat to 'moral order', the second is posing of potential solutions through 'social control', and the third element is governmentality through 'self-regulation' (Critcher 2009).4.2 Using Critcher's (2009) framework, we can see how current media discourses of parenting culture map onto a generalised pattern of moral regulation, albeit in a fluid and diverse form. Poor parenting is increasingly seen as an important threat to 'moral order' as evidenced through discourses on antisocial families (Garrett 2007). In relation to 'social control', we can see policy initiatives focusing on parenting. Some explicitly target 'poor' parenting through means including Parenting Orders, while others more generally aim to 'improve outcomes' through initiatives that seek to modify parenting style, often directed at those living in areas of deprivation or at particular groups of parents such as teenage mothers. Moreover, the emphasis is not on structural elements shaping 'outcomes' such as poverty and unemployment but individual behaviours. Individuals are thus required to self-monitor and regulate their behaviour or be subject to sanctions, from strong disapproval in the case of infringements such as smoking whilst pregnant (Oaks 2000), to criminalisation for more serious breaches (Arthur 2005). Consequently, this framework allows us to analyse media discourses about behaviour during pregnancy as part of a broader moralizing agenda.

4.3 Pulling these issues together, this paper will now outline the dominant frames identified within UK newspaper coverage of drinking in pregnancy. It will show similarities and differences to those frames identified by Connolly-Ahern and Broadway (2008) and so identify the particular features of moralizing narratives in British newspapers. It will also argue that although critiques of the new abstinence position are common, they do not necessarily undermine the moralizing messages that promote self-regulation as a solution to this social issue.

Methodology

5.1 All articles in UK national newspapers mentioning FASD were retrieved from the Lexis-Nexis database up to the end of 2008. The database has archives that go back to the mid 1980s although different newspapers have joined Lexis-Nexis at different points in time. All weekday newspapers have been included since 2000, and Sunday newspapers since 2002. In addition, a search was carried out on alcohol and pregnancy as major mentions to ensure a comprehensive database was established. Using these search terms 1741 potential articles (FASD 373, alcohol and pregnancy 1368) were identified. The articles retrieved were initially screened to remove duplicate articles[3] and articles which appeared in Irish editions of the papers[4]. They were then screened for relevance to the study. In the dataset arising from the search on the term FASD, articles were excluded if they only mentioned FASD in passing (for example a story on patient records found in a disused hospital where one was of a patient with FAS). In the wider alcohol and pregnancy search, articles were added to the FASD dataset if they mentioned the possible impact drinking alcohol had on the development of the foetus. For example, articles which stated that alcohol could cause birth defects or intellectual impairments were included, whereas articles discussing the impact on conception or miscarriage were not.5.2 After screening, the database consisted of 401 articles which were imported into NVIVO for analysis. The articles were all read by at least two of the research team and a thematic coding scheme was developed. Particular attention was paid to the 'triggering event', any narratives or templates that could be identified, the 'experts' whose opinions were drawn on, and the broader context situating the story.

Patterns of reporting

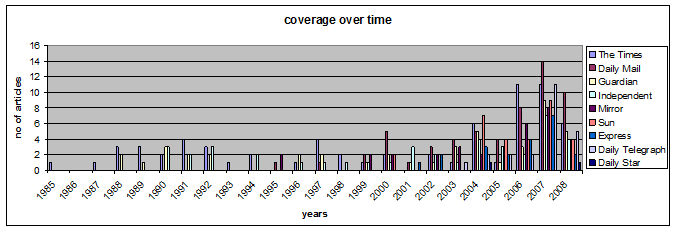

6.1 Analysis of the articles over time showed a marked increase in the frequency with which the issue was reported. Although some of this is to be expected, as not all the newspapers were in the database before 2000, even since then interest has grown. Table 1 sets out how the volume of coverage has grown over time in the daily newspapers. More detail about the number of stories in the papers can be seen in Tables 2 and 3.

|

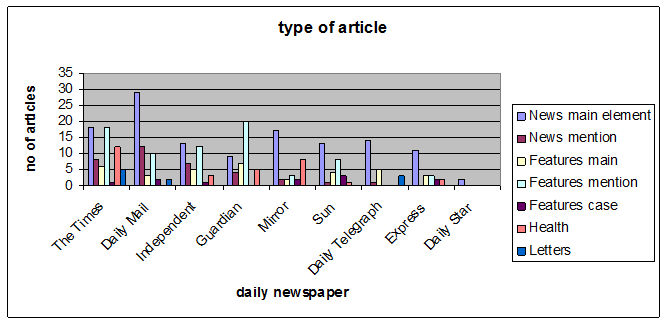

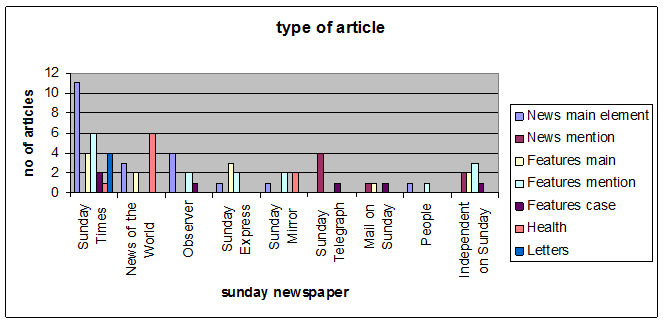

6.2 The articles were also coded for the format of the story. They were divided into 4 main categories: news, feature, medical advice, or letter to the editor. Stories were coded into the news category if the story was mainly the reporting of 'facts' about FASD. This could be as a major element such as a report about a new piece of research into the impact of alcohol on pregnancy, or changes in official drinking guidelines. Stories were coded as a mention in a news item if FASD was referred to, but was not the main focus; for example, a story on smoking rates and pregnancy where alcohol was also mentioned. Articles were coded as features if they were editorials or lifestyle pieces. Features were subdivided into 3 categories: main focus, mention or case study. In a similar divide to that used for news articles, main and mentions were categorised in relation to the focus of the article. For example a main article would be an opinion piece about government guidelines, and a mention would be a general lifestyle piece on pregnancy where FASD was mentioned. Case studies were stories focusing on the lives of a carer or person (or both) with FASD. The third main category, health advice, contained items written by the newspaper's 'in-house' medical professionals. This could be in 'health' pages or in response to particular health questions posed by readers. The final category contained letters to the editor following the publication of particular articles on alcohol and pregnancy.

|

|

6.3 The first item about FASD identified in the database was published in 1985. The Times (2/8/1985) reported that an article had been published in the British Medical Journal on the importance of nutrition in pregnancy, including the risk of FAS in 'heavy drinking mothers'. This type of mention was typical of the 1980s where newspapers reported on a conference or other research-related activity. The reports were sporadic, with notably no secondary articles or discussion generated. The other type of coverage in the 1980s occurred in health advice. For example, the Medical Briefing in The Times (27/4/1989) stressed that moderate drinking was considered to be low risk so the restriction of alcohol rather than abstention during pregnancy was the only measure called for.

6.4 The issue began to be an area for more discussion from 1989. This seemed to be triggered by two events in the US, the introduction of warning labels on alcoholic drinks, and coverage of the Thorp case. In this case, a whiskey distilling company was being taken to court in a case brought on behalf of a child with FASD for failing to warn people about the dangers of drinking during pregnancy (see Golden (2005) for a fuller history). The coverage remained sporadic in the 1990s, although more follow up or discussion pieces often linked to news stories of FASD began to emerge. Two trends can be identified in these stories. First, heavy drinking was always deemed to be the main risk, with women constantly reassured that low alcohol consumption was not something to be concerned about. The second trend was that the abstinence position in the US was considered unnecessary and linked to that country's 'litigation' culture, rather than a response to any real risk. This is illustrated by the following extract from a feature in the Guardian:

The case for abstinence is not based on evidence. It is based on the logic of better safe than sorry. It is tempting, especially for an expectant mother, to say that any risk, however small or theoretical, is too great. But that is absurd. Everything about light drinking during pregnancy makes it the kind of theoretical risk that Americans are unlikely to evaluate sensibly. Doctors are innately cautious and made more so by lawyers hovering overhead with malpractice lawsuits (27/05/1991)

6.5 It is in the early 2000s that we see coverage of the issue increasing, particularly from 2002. This timeframe coincides with the formation of UK based FASD organisations (lobby groups that seek to raise awareness of FASD and promote alcohol abstinence in pregnancy); the first debate in Parliament on the issue (2004); and the moves to introduce warning labels on alcohol containers in the UK. The coverage at this time also included reports about and discussion of the changes to the official guidance on the recommended level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. (In 2007 the DH for the first time advised 'pregnant women' and those 'planning to become pregnant' to 'avoid alcohol' (see Lowe and Lee 2010)). Articles debated the differences between the advice given by different official bodies, and critiques began to emerge on the abstinence position now promoted by the government.

6.6 In this coverage, contradictions appear both within and between papers over the risks of low to moderate alcohol consumption in pregnancy. Individual papers did not seem to take a particular stance on the issue; instead commentators could support either position. For example, the Sun carried a short news story on the 26/3/2008 reporting that the abstinence position had been adopted by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), as set out in its revised guidance, with the headline 'Drink will hurt baby'. The report did not discuss the advice, with the implication that drinking alcohol should be seen as potentially harmful to the foetus. The following day it carried a longer feature challenging the new advice with the headline 'How much booze is bad for your baby?' (27/03/08). Although the article stated 'experts don't agree', the experts quoted in the feature supported the view that there was no medical evidence that justified the complete abstinence position. Consequently readers of the Sun could have received either or both pieces of health information depending on how often they read the paper.

6.7 Although the three frames of coverage found by Connolly-Ahern and Broadway (2008) did occur to some extent, they did not seem to adequately represent the dominant frames which emerged from analysis of the British coverage. Instead, the coverage of FASD could be seen to link to wider recurrent frames in the UK media. The first frame to arise was the extent to which alcohol is a problem in society; the second was about the advice or warnings given to women; and the final frame centred on policing pregnancy. Quotations used to illustrate the themes are representative of the emerging themes, unless otherwise stated.

Alcohol as a problem?

7.1 Many of the mentions of FASD, unsurprisingly, occur in articles which discuss alcohol as a social problem. In this theme, we can see a marked shift over time. The early coverage of FASD in British newspapers indicated that it was a problem elsewhere, particularly the US, and that concerns about it are reactionary, unnecessary and even perhaps bizarre. As well as the Guardian article quoted above, the Independent and The Times also linked concerns about FASD to a neo-prohibition movement. In many of these articles, discussion considers the proliferation of warnings about drinking alcohol in general, and the emergence of the concept FASD is deemed to be part of this development. For example in an article published in 1992 the Independent starts by outlining the case of two US waiters who lost their jobs after a pregnant woman complained about their attitude towards her ordering alcohol. It links this issue to a wider concern that alcohol consumption was becoming viewed as always problematic: 'So, be warned. Despite the evidence of centuries of moderate alcohol use, in the eyes of the state there is no balance between the benefits and dangers of alcohol; only danger (04/01/1992)'. Similar warnings about neo-prohibition are to be found in The Times. For example, an article from 1994 which reports on the potential benefits of drinking wine moderately specifically states that during pregnancy, red wine can help reduce the risk of anaemia and argues, 'Despite the insidious moves of the neo-prohibitionists, the benefits of wine-drinking are starting to get the press they deserve' (13/05/1994). These articles, while not denying that excessive alcohol can lead to congenital problems in the foetus, represent the heightened attention paid to alcohol consumption in pregnancy as an extreme reaction within a broader anti-alcohol context. Over time, articles in our database which extol the virtues of alcohol decline, but the notion that FASD is being constructed as a disproportionate risk also emerges in the other frames.7.2 Within the general frame of alcohol as a (potential) problem, FASD was also mentioned as an outcome of colonialism. Articles discussing this idea are found particularly in the Broadsheet papers and the emphasis is on FASD as an outcome of social and economic deprivation within the context of history. Poor and marginalised communities such as Native-Americans and Inuit are described as being 'blighted' by alcohol, with large numbers of FASD cases. For example, The Times ran an article in 1990 on the struggles of different tribes over land and resources which included a description of a project which worked to reduce alcohol dependency and the address the high number of children born with FASD (1/9/1990). Some of these articles, for example one published in the Sunday Times (05/08/1990), directly report on the writing of Michael Dorris whose book The Broken Cord highlighted the issue of FASD in Native-American communities. Consequently, FASD in these types of articles is a problem of the 'other', and whilst they do provide descriptions of the 'victims' of FASD as found by Connolly-Ahern and Broadway (2008), the impact is less powerful in UK reporting as the problem is overtly located elsewhere.

7.3 However, over time alcohol consumption is increasingly seen as a problem within the UK. As others have noted, from the late 1990s media coverage begins to name binge-drinking (Measham 2005) and women's drinking (Day et al 2004) as growing social problems. Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder begins to be identified as one of the concerns that we should have about alcohol consumption in general. In the majority of cases in this frame, the 'story' is a reported rise in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related crime or health issues, with FASD mentioned as a potential problem. For example the Daily Mail ran a feature on 02/05/2000 entitled 'What alcohol really does to your body' following a reported rise in women's drinking. It sets out a huge range of health issues that it links to alcohol consumption including brittle nails, weight gain, heart disease and cirrhosis of the liver. Within this article it states that alcohol can cause 'brain damage and learning disabilities' and that 'another risk' is FAS. The separation of FAS from other alcohol-linked congenital anomies is unusual, but apart from that, this article is typical of the way in which FASD is evoked as part of the 'problem' of alcohol consumption. Similar articles ran in the Sun (8/11/2000), the Mirror (6/2/2003) and the Sunday Times (9/11/2008). In these articles, although a brief description is given, FASD is rarely discussed in any detail. As such the implications of FASD are left implicit rather than being made explicit.

7.4 This is in contrast to articles that focus on a particular person with FASD. In these, the implications of FASD are named and clearly linked to alcohol abuse. Many of the case studies mention adopted parents or carers rather than birth mothers. Here we can see both the 'dangerous women' and 'victim' themes that emerge in Connolly-Ahern and Broadway's (2008) study. Many of the cases are repeated in different papers. For example, 'Dominic's story' is related by his foster mother. He is described in different newspapers as a 'damaged child' (Sunday Times 22/04/2007) 'all because of his mother's heavy drinking' (Daily Mail 14/09/2004). Birth mothers appear less frequently, and their alcohol consumption is discussed more sympathetically. In the Mirror, a birth mother explains how she had not realised that her level of drinking was above accepted levels and 'no one warned me it was dangerous' (2/10/2006). The case studies both describe alcohol as a social problem and lay out detailed implications for the direct 'victims', those with FASD and the struggles of those that care for them. However case studies form a minority of FASD stories.

Women warned?

8.1 More of the articles published since the late 1990s are reports of research and/or guidance to pregnant women that link (or dismiss the link between) the consumption of alcohol to FASD. Often these are without commentary, and convey the 'message' of the original source of the story. Some of these reports are very similar in different papers, suggesting that they are written from press releases. For the majority of the earlier reports, the tone of reporting is not judgemental against pregnant women who drink, but sets out health guidance that it is argued they may need to consider, as the following examples show:Pregnant women who drink just four glasses of wine a week are putting the health of their babies at risk. Research presented at the annual conference of the British Psychological Society in Belfast yesterday showed that drinking, even in moderate amounts, is just as harmful to the unborn child as smoking. (Independent (9/4/1999)

A warning went out to mothers-to-be last night that even a tiny amount of alcohol can damage their babies. (Daily Mail 27/1/2000)

Pregnant women who drink even moderate amounts of alcohol could damage their babies, researchers warned yesterday. (Mirror 15/8/2005)

8.2 This type of story implies that the information is new and, as such, women could not necessarily be aware of the 'danger' before reading the report. This can be seen in most clearly in the quote from the Independent in which the danger from smoking is seen as a common reference point for the new information.

8.3 It is in these articles that the role of specific claimsmakers emerges most. Some of the reporting emerges from press coverage of events or campaigns that are initiated or supported by FASD organisations for example, coverage of conferences (e.g. Express, Daily Telegraph 14/09/2004) or the campaign for there to be warning labels on alcoholic drinks (e.g. Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail 10/02/2007). In a similar way to the reports discussed above about new research, articles of this kind do not usually challenge the claims made by lobby groups, nor is their stance on the issue advocating alcohol abstinence brought into question. Reporting rarely refers to any other prior coverage on the issue or to wider debates. Although some articles are more forceful than others in the way they report about the 'danger' of alcohol, the implicit message in them all is that there is a new, important 'warning' that 'responsible' women need to take on board.

8.4 In contrast, it is when coverage is reporting official policy guidance on alcohol consumption that the issue becomes one of debate and conflict. Two issues emerge in newspaper stories of this kind. First, it is argued that the level of uncertainty about the 'correct' advice that should be given to women is problematic, and that there needs to be clarity on the issue. The second issue is that of the 'nanny-state'; that in general terms, the government should refrain from telling people what to do in their private lives. Clearly, there is a conflict between these two ideas. A standard policy would be a state-sponsored directive about an area of personal life, and interestingly both positions were sometimes argued for in a single newspaper (although not usually in the same article). To illustrate this phenomenon, examples have been used from the Daily Mail, but similar conflicting positions could be seen in other papers:

Women should not drink at all during pregnancy to avoid harming their baby, according to the latest government advice ( ). In an apparent contradiction, the Government insists women who have followed previous guidance have not put their babies at risk (25/5/2007)

Why our nanny state should stay mum' (headline). ( ) The Department of Health has warned that pregnant mothers should stop drinking alcohol altogether. But if modest consumption of wine during pregnancy was as bad as they claim, then all French people would be brain-damaged' (30/5/2007)

8.5 The two quotes above occurred in stories following the announcement by the DH in May 2007 that it was changing its advice to recommend abstinence. The first quote reports on the change, but introduced conflict in the story by picking up on the 'non-harm' that apparently resulted from the previous guidance. This introduces the idea that clarity in the guidance is preferable and uncertainty is to be avoided. The second article, which followed a few days later, links the advice to the 'nanny-state' discourse, suggesting that no guidance is required. This wider discourse is part of a broader critique by commentators that governments should not interfere with the 'private' lives of its citizens (see Cottam 2005 for a wider debate on the 'nanny-state' critique of public health measures). This contradiction continues in later articles in the Daily Mail, which focus on the difference between the DH 2007 guidance, and that from NICE which did not recommend abstinence in 2007 but then did so in revised guidance published in 2008:

Confusion over whether women can safely drink during pregnancy deepened yesterday with new guidance stating a small glass of wine a day is okay ( .) (it) will leave women wondering which set of 'official' guidelines to follow. (11/10/2007)

First the experts said you shouldn't drink. Then they said pregnant women could have a glass every so often. And after months of confusion, you might hope the health watchdog's latest advice on alcohol for expectant mothers would finally clear things up. But is seems nothing is that simple. (26/3/2008)

(about a statement from the 'drink and drugs' tsar) The message that women should not drink during pregnancy is surely being relayed in every GP surgery and pre-natal clinic, so why do we needed a public announcement? The undertones of the Nanny State in these endless, sermonising utterances from public officials who need to find some means of justifying their existence is becoming increasingly wearisome to the public. (9/06/2008)

8.6 In these three quotes we can see the continuation of the conflicting themes of uncertainty over guidance as a failing, and that guidance is unwarranted anyway. The stories which referred to 'conflict' or 'confusion' in different guidance rarely drew attention to this as a possible outcome of uncertainty or a lack of evidence. Both of these stances in the newspapers also highlight the way in which health issues can become politicized. As Boyce (2007) has shown in the MMR debate, media stances on health stories can be focused on support or challenge to a particular government, and as such debate about health implications per se can become a secondary issue.

8.7 It is only in a minority of articles that women's drinking behaviour is identified as definitely problematic. These often refer to the wider discourses of 'binge-drinking'. For example, a headline in the Sun in 2006 stated that babies were being harmed by 'boozy mums-to be' (30/10/2006) and the Sunday Times argued that 'babies are being left brain-damaged ( ) by their binge-drinking mothers'. (6/8/2006). Yet these articles can also illustrate the extreme differences in the numbers claimed to be affected; the Sun reported a claim of 'up to 18,000' babies a year in the UK based on 'a new study', yet the evidence presented to the Sunday Times found 'at least 9' a year in Scotland. The scale of the disparity between these two figures means that it is highly unlikely to be an outcome of geographic distribution. They are more likely an outcome of the difference between cases actually diagnosed by medical professionals, and estimates provided by FASD organisations.

8.8 In the majority, the articles that report research or guidance seek to warn women about drinking alcohol during pregnancy rather than decry their behaviour. Consequently, these articles implicitly or explicitly assume that the role of women during pregnancy is to minimize any potential risk to the foetus (this has been explored more fully elsewhere, for example see Lowe and Lee 2010). The focus on the primacy of foetal well-being, which can be linked to trends in broader parenting culture, is also a feature in the final theme found in the articles, and it is to this we now turn.

Pregnancy policed?

9.1 The final major frame detected is where FASD appears in the more direct advice about how to manage pregnancy. General advice on pregnancy is a regular feature of many newspapers. Sometimes this is communicated through letters and advice columns written by medical professionals, but there are also often newspaper features that outline current health information, and many of these discuss FASD. Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders may be reported about alongside other guidance, without any broader discussion, or articles may discuss the level of alcohol that is likely to be 'safe', as the following examples illustrate:What's safe (and what's not) when you are pregnant (headline) ( ) if you have a drink your baby will be having one too- and the effects can last a lifetime ( ) up to 6,000 babies a year are born with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, ( ) find a safer alternative by replacing a tipple with a non-alcoholic beer and wine. (Mirror 31/7/2007)

What you need to know about eating for two (headline) ( ) Heavy drinking during early pregnancy can greatly increase the risk of foetal alcohol syndrome and birth defects. Nobody knows how much or how little- can harm a developing baby, so the advice is extremely cautious: the Department of Health recently recommended that pregnant women steer clear of alcohol altogether. ( ) Basically, if you are getting drunk, then it is not good for the baby but an odd glass of wine, ( ) or in my case, a half pint of Guinness (again, very good for its iron content), could be quite good for you. (Express 2/10/2007).

9.2 Other articles are far more critical of the advice given to pregnant women. Many of these raise the issue of the policing of pregnancy, commenting on the ways in which the advice increasingly given to pregnant women can lead them to have restricted lives, and that it raises anxiety levels unnecessarily. This type of article was more frequently published in broadsheets than tabloid papers, but did feature in both. Typical examples are:

This new zero tolerance of alcohol is too harsh for mothers-to-be who already face a battery of dread rules about what they should avoid even ready-washed, bagged salad. If the health police aren't careful, they'll make pregnant women too terrified to breathe. And that wouldn't do the baby much good either. (Guardian 26/5/2007)

I'm a bad mother and my baby's not even born. No, I am not a chain-smoking binge drinker but I do enjoy the occasional glass of wine. I drink coffee, eat seafood and, may God call me a sinner, I also wear make-up and go to the hairdressers for a regular cut and colour. ( ) To hear that I could be creating a lifetime of misery for my baby is a terrifying prospect but, short of locking myself away in a bubble with only the purest of oxygen ( ) I'm not entirely sure what the white coats expect me to do. (Sunday Express 11/09/2005)

9.3 In relation to FASD, this type of article often argues that the abstinence advice on alcohol consumption is unwarranted due to lack of evidence, either from research or on the basis that previous generations of women have drunk alcohol without noticeable effects. For example:

The trouble with crying wolf, as the fable tells us, is that it only makes your audience less likely to believe in real dangers ( ) Foetal alcohol spectrum disorder allegedly causes attention deficit disorder. ( ) A generation or two ago, as my mother's friends never tire of telling me, everyone drank and smoked throughout their pregnancies. This may not have done much for their offspring's health or prospects (I could have been a catwalk model, had I not been stunted by my mother's 60-a-day habit), but, mysteriously, not one of their children was afflicted by ADHD. (Independent 26/05/2007)

9.4 Yet although these articles appear highly critical on the surface, they do not necessarily challenge the ideals of motherhood that form part of contemporary parenting culture. Their arguments are based on the premise that the abstinence position is not based on evidence, but the notion that pregnancy does not necessarily warrant women making significant changes to their behaviour is rarely challenged. This is made clearer where the critique of abstinence is based not just on lack of evidence, but also rests on the claim that 'responsible' women do not need to be told to change. For example: It is time that our health educators acknowledged that the vast majority of women behave with great tenderness and concern towards their unborn child. (Daily Mail 30/05/2007)

Common sense tells mums-to-be not to binge drink. (Sun 14/11/2007)

Most women are extremely careful of their unborn babies. (Sunday Times 27/05/2007)

9.5 Consequently, the overall message is that the advice on alcohol and pregnancy is likely to be unwarranted as responsible women always act in their best interests of their foetus anyway and so do change how they behave. Indeed only in a very small minority of articles is the suggestion made that pregnant women might want or have a right to their own lives, and this is often qualified. For example, the Sunday Express article about being a 'bad mother' quoted above states, 'Women do not exist just for the sake of their babies' but this comes after stating 'naturally, I don't want to do anything that will put my child's development and general wellbeing at risk' (11/09/2005). Similarly an article in the Guardian about criminal cases based on foetal harm argues that, 'it is a worrying sign that US women are expected to treat themselves as incubators first, individuals second' but goes on to suggest that women need 'support' rather than a 'prison sentence' (04/09/2006). Consequently, the message that 'responsible motherhood' begins during pregnancy is clear, whether or not an article supports abstinence from alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

Some thoughts on FASD debates and parenting cultures

10.1 As this paper has shown, over time there has been a marked increase in the discussion of FASD and changes in the dominant frames shaping reporting. The combination of a rising concern about alcohol consumption generally, the emergence of claimsmakers seeking to highlight the specific problem of FASD, and changing understandings of responsible pregnancy, can all be understood as contributing to why FASD, despite the lack of new evidence, came to be seen as a (potential) social problem in the UK.10.2 The moralizing framework surrounding alcohol constructs its consumption as increasingly problematic. Whilst in general terms, this is linked to concerns about antisocial behaviour (DH 2007b), alcohol consumption is seen as particularly problematic for young women (Day et al 2004). The association between alcohol consumption and inappropriate sexuality has already been firmly established in existing social concerns about teenage pregnancy (Wilson and Huntington 2006). More generally, parenting is now deemed to be both the cause of, and possible solution to, antisocial behaviour (Goldson and Jamieson 2002). In this context, it is not surprising that FASD emerges as an issue. Within the frame of alcohol as a problem, FASD can thus be seen as a symbol of antisocial parents. Although the implications for the (potentially) damaged foetus are not discussed at length in this frame, they are clearly drawn upon, and reinforce wider concerns about irresponsible women.

10.3 It is in the second frame discussed above, 'women warned', that the role of claimsmakers emerges most strongly. Early articles reported the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy as a 'new' potential concern, but rarely commentated on it further. The formation of lobbying organisations and individuals, willing to publicise and comment on the issues, appears to have raised the profile of FASD within the UK, in particular by providing statistics and typifications of victims to illustrate the scale and seriousness of the problem. As Boyce (2007) has shown, health pressure groups can directly impact on the way that an issue is framed. Yet this could not have happened without the readiness by the national media to take them seriously as commentators, and endorse not challenge their case. As Reinarman (1979) has showed, vocalising an issue is not enough. To be taken seriously, the 'problem' identified needs to fit within broader public and political concerns. Consequently, in order to be considered (and quoted) as credible sources, FASD organisations need to articulate their concerns in a way that 'fits' with broader discourses. FASD is thus represented as an issue that can be linked to wider concerns about alcohol consumption, but also as one resonant with the emergence of a 'public foetus' (Duden 1993), and it is the latter that provides the direct link to the larger parenting culture. The 'public foetus' has rolled back the timeframe of parenting so that 'good mothering' becomes a requirement of pregnancy.

10.4 To what extent was opposition to this development articulated? As noted above, it was striking that there was an almost total absence of direct criticism of the claims made by FASD organisations. Although some critiques of increasing policy interference in 'private' lives emerged in the newspaper coverage analysed, in particular in relation to the changes in abstinence policies, these rarely went beyond a complaint about the current government, thus the wider potential challenge to the implications of the abstinence policy were largely unaddressed. The final frame identified, of 'pregnancy policed' offered the most critique albeit indirect - of the construction of FASD emanating from lobby groups. Although some of the stories and reports on the 'right' and 'wrong' behaviours during pregnancy accepted the abstinence position these groups, and latterly government policy, promote, many more rejected this as unwarranted and overly restrictive. Yet, regardless of their position on alcohol consumption, the majority of these articles took for granted the need for women to behave in a way that promoted foetal health, regardless of the impact on women. 'Responsible' motherhood, it was uniformly assumed, started during (or before) pregnancy. Although the source of relevant expertise was debated, it was also assumed that responsibility entailed following 'expert' advice. Thus the imperative to avoid 'risk' if a woman is to behave responsibly was not necessarily undermined by the rejection of abstinence policy. As a Guardian reporter stated at a beginning of an article about pregnancy and health:

.amid the barrage of advice, what should you take seriously, and what can you ignore? What's right, and what's just scary nonsense? I decided to do some research on the subject, rather than just taking the government's word for it. (29/05/2007)Consequently, the discourse of intensive motherhood, whereby expert advice is needed to ensure the best outcomes for a child (Lee 2008), is clearly shown to begin during (if not) before pregnancy.

Conclusion

11.1 The research reported here suggests that from a sociological perspective, the issue of FASD bridges contemporary concerns about alcohol consumption and (potentially deviant) parenting cultures. Whilst no clear divides were identified between different newspapers, and none appeared to have an editorial line on the issue, the increasing coverage and changes in reporting of FASD appear linked to broader discursive shifts in these areas. These trends appeared to be given form, and articulated in a way newspapers then reported and discussed, by FASD organisations and changes in policy.11.2 Following Critcher's (2009) framework, alcohol consumption during pregnancy emerged from this analysis overall as a threat to 'moral order' through irresponsible parenting. Hence to be a 'good mother', women should voluntarily abstain from alcohol. Whilst this message promoting self-regulation was not reported uncritically, the reaction was muted as it framed within ideas of the 'nanny-state'. This critique forms part of a more general attack on the government or deems alcohol abstinence advocacy unnecessary as 'good mothers' do not need to be told to change their behaviour for the sake of the foetus. Consequently despite some journalists paying attention to the lack of evidence underpinning the claim that pregnant women should not drink alcohol at all, no comprehensive critique of the democratisation of FAS from alcoholic to all women emerged in the media. This lack of alternative perspective in an important arena for public debate draws attention to the overall success of the moralizing framework surrounding FASD, and it highlights the strength of the cultural shift to move 'good parenting' backwards towards preconception.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the British Academy for funding this research project. Thanks also to the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Notes

1 NOFAS UK is a charity which seeks to raise awareness of FASD and support people affected by the condition. NOFAS UK is linked to similar organisations in other countries.2 The HES state that this is based on research evidence of incidence elsewhere but no specific references are ever given by them.

3 Where the same story was of a different length in different editions, the longer version was included in the dataset.

4 Many national papers have regional editions which can differ in content or tone from each other. Articles were removed if they explicitly stated they were in an Irish edition of the paper. This information may not have been available for all papers.

References

ARMSTRONG, E. (2003). Conceiving risk, bearing responsibility: Fetal alcohol syndrome and the diagnosis of moral disorder. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

ARTHUR, R. (2005) 'Punishing Parents for the Crimes of their Children'. The Howard Journal Vol 44 No 3. pp. 233253 [doi:10.1111/j.1468-2311.2005.00370.x]

BOYCE, T. (2007) Health, Risk and News: The MMR Vaccine and the Media New York: Peter Lang

BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION (2007) Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals. BMA: London.

CONNOLLY-AHERN, C. and BROADWAY, SC. (2008) ''To Booze or not to booze?' Newspaper coverage of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders' Science Communication 29(3) pp 362-385 [doi:10.1177/1075547007313031]

COTTAM, R. (2005) 'Is public health coercive health?' Lancet 366 pp 1592-1594 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67644-1]

CRITCHER, C. (2009) 'Widening the Focus: Moral panics as Moral Regulation' British Journal of Criminology 49 pp 17-34 [doi:10.1093/bjc/azn040]

DAY, K., GOUGH, B. and MCFADDEN, M. (2004) 'Warning! Alcohol can seriously damage your feminine health. A discourse analysis of recent British Newspaper coverage of women and drinking'. Feminist Media Studies 4 (2) pp 165-183 [doi:10.1080/1468077042000251238]

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (2007a). Updated alcohol advice for pregnant women <http://www.direct.gov.uk/en/Nl1/Newsroom/DG_068143> accessed 30/05/2007

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (2007b). Safe, Sensible, Social: The next steps in the National Alcohol Strategy . Department of Health: London

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (2008). Pregnancy and Alcohol. Department of Health: London.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (2009). The Pregnancy Book. Department of Health: London.

DUDEN, B. (1993) Disembodying Women: Perspectives on Pregnancy and the Unborn, Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

GARRETT, P.M. (2007) ''Sinbin' solutions: The 'pioneer' projects for 'problem families' and the forgetfulness of social policy research' Critical Social Policy 27; pp 203-230 [doi:10.1177/026108306075711]

GOLDEN, J. (2005) Message in a Bottle, the making of fetal alcohol syndrome. Cambridge Mass. and London: Harvard University Press.

GOLDSON, B. and JAMIESON, J. (2002) 'Youth Crime, the 'Parenting Deficit' and State Intervention: A Contextual Critique' Youth Justice Vol. 2 No. 2 pp 82-99 [doi:10.1177/147322540200200203]

HES ONLINE (2007). Pregnant women and alcohol. <www.hesonline.nhs.uk> (Accessed 20 July 2009)

HIER, S. (2008) 'Thinking beyond moral panic: Risk, responsibility, and the politics of moralization'. Theoretical Criminology 12(2) pp 173:190

HODGETTS, D., CHAMBERLAIN, K., SCAMMELL, M., KARAPU, R. and NIKORA, L.W. (2007) 'Constructing health news: possibilities for a civic-oriented journalism'. Health Vol 12(1): pp 43 66

JONES, K. and SMITH, D. (1973). 'Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy'. Lancet: 2, pp 999-1001. [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(73)91092-1]

LARSSON, A., OXMAN, A., CARLING, C. and HERRIN, J. (2003). 'Medical messages in the media barriers and solutions to improving medical journalism'. Health Expectations, 6, pp 32331. [doi:10.1046/j.1369-7625.2003.00228.x]

LEE, E (2008) 'Living with risk in the age of 'intensive motherhood': Maternal identity and infant feeding', Health, Risk & Society, 10: 5, pp467-477 [doi:10.1080/13698570802383432]

LOWE, P. AND LEE, E (2010) 'Advocating alcohol abstinence to pregnant women: Some observations about British policy' Health, Risk & Society, Vol 12, No 4 pp 301 - 311 [doi:10.1080/13698571003789690]

MEASHAM, F. and BRAIN, K. (2005) ''Binge' Drinking, British Alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication' Crime, Media Culture 1 No 3 pp 262-283 [doi:10.1177/1741659005057641]

MILLER, P.G.(2007) 'Media reports of heroin overdose spates: Public health messages, moral panics or risk advertisements?' Critical Public Health,17 (2) pp 113:121

OAKS, L. (2000) 'Smoke-filled wombs and fragile fetuses: the social politics of fetal representation'. Signs 26(1) pp63-108 [doi:10.1086/495568]

REINARMAN, C. (1979) 'Moral entrepreneurs and political economy: historical and ethnographic notes on the construction of the Cocaine menace' Contemporary Crises 3 pp225-254 [doi:10.1007/BF00730860]

SEALE, C. (2002) Media and Health London: Sage

WILSON, K., CODE, C., DORNAN, C., AHMAD, N., HΙBERT, P. and GRAHAM, I. (2004) 'The reporting of theoretical health risks by the media: Canadian newspaper reporting of potential blood transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease'. BMC Public Health 4:1 <http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/4/1>

WILSON, H., and HUNTINGTON, A. (2006). Deviant (M)others: The construction of teenage motherhood in contemporary discourse. Journal of Social Policy, pp 35, 59-76.