Apocalypse in the Long Run: Reflections on Huge Comparisons in the Study of Modernity

by John R. Hall

University of California-Davis

Sociological Research Online 14(5)10

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/5/10.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.2022

Received: 22 Jun 2009 Accepted: 20 Oct 2009 Published: 30 Nov 2009

Abstract

Methodologies of historical sociology face research problems centered on the instability of historical referents, their historical non-independence, and the privileging of objective time of the clock and calendar. The present essay, by reflecting on an analysis of the apocalyptic in the long run (Hall 2009), proposes the potential to solve these problems by way of a phenomenology of history, which analyzes the enactment and interplay of multiple social temporalities. Whereas high-modern theories of modernity tended to portray a secular trend toward the triumph of rationalized social order centred in diachronic time, analysis of the historical emergence of apocalyptic times in relation to other temporalities - especially objective (or diachronic) temporalities, the here-and-now, and the collective synchronic - reveals that the apocalyptic has survived within modernity through the articulation of rationalized diachronic time with the sacred strategic time of apocalyptically framed 'holy war.' Overall, the 'empire of modernity' is a hybrid formation that bridges diachronic and strategic temporalities. Despite diachronic developments that tend toward what Habermas described as the colonization of the lifeworld, a phenomenological analysis suggests the durability of the here-and-now and collective synchronic times. These analyses unveil a research agenda that deconstructs the high-modern 'past' versus 'present' binary in favour of a model that analyzes the interplay of multiple social forms, and thus encourages a retheorization of modernity as 'recomposition' encompassing multiple temporalities.

Keywords: Conflict, Generalization, Historical Sociology, Historicism, Lifeworld, Methodology, Modernity, Phenomenology, Religion, Temporality, Theory

Introduction

1.1 Until recently, most academics relegated the Apocalypse to the realm of prophetic visions that served as grist for cartoons in The New Yorker. Even today, historical sociologists who study revolutions, social movements, work, bureaucracies, or families might not grant equivalent analytic status to the apocalyptic. If they did, central problems would remain, notably, how to salvage comparative sociological analysis in the face of slack relationships between popular uses of apocalyptic language and the seemingly ephemeral things to which they are said to refer. Surely, to study the apocalyptic in the long run is to enter a hermeneutic house of bedlam. Yet recent mainstream invocations of the apocalyptic (for example, in The Times (UK), The New York Times, The Times of India, and The Japan Times) suggest that we are already in that hermeneutic house. The question, then, is how to make sense of this (for us) historically unprecedented situation. In this essay, I argue that pursuing a ‘phenomenology’ of history to consider the apocalyptic in the long term unexpectedly shifts our theories of modernity, and in the bargain, revises our toolkit for studying large-scale social processes and long-term historical change.1.2 What I will call ‘the apocalyptic’ encompasses a broad range of beliefs, actions, and social processes centred on cultural disjunctures concerned with ‘the end of the world’ and thereafter. As the meaning of the ancient Greek word apokalyptein suggests, an apocalyptic crisis is marked by ‘disclosure.’ In ways that people often read the Bible's New Testament, disclosure means ‘revelation’ of God's will, purpose, or plan, either through prophecy or in events themselves. However, apocalypse can be shifted out of its typically religious register by noting that apocalyptic texts usually are not about the End, but about the Present Crisis.

1.3 Ordinarily, the culture of an established social order, especially its religious legitimations, screens off everyday life from the harsh light of ultimate reality (Berger 1967: chap. 2). However, sometimes powerful, seemingly uncontrollable forces envelop collective social experience. Apocalypse as disclosure unveils aspects of the human condition or present historical moment that pierce the protective screen, just as a loved one's death proves traumatic for those who survive, but on a wider scale. Previously taken-for-granted understandings of ‘how things are’ break down. Historically new possibilities are revealed, awesome enough to undermine normal perceptions of reality for those involved, thereby leading people to act in unprecedented ways, outside their everyday routines. Sociologically, then, apocalypse encompasses more than the end time of God's final judgment, or some absolute and final battle of Armageddon. Rather than the actual end of the world, the apocalypse is typically ‘the end of the world as we know it,’ an extreme social and cultural disjuncture in which dramatic events reshape the relations of many individuals to history at once.

1.4 If the apocalyptic is construed in these terms, might it be analyzed like any other sociohistorical phenomenon? My central thesis is that studying the apocalypse brings to the fore in a distilled way central problems about whether and how historical/comparative sociology can contribute to understanding connections and parallels between past and present. Indeed, studying the apocalypse alters our terms for engaging in comparative and historical sociology more generally, and for understanding modernity.

Past, present, and historical sociology

2.1 Three general problems plaguing comparative and historical inquiry seem important to me.- Issue #1: Concepts are historically and comparatively unstable in their referents. Thus, as Margaret Somers (1997) demonstrated, the concept of ‘citizenship’ cannot be defined in a transhistorical, universalistic way, at least, not without either excluding alternative understandings of citizenship that have been historically important, or embracing a particular (and denuded) modern concept of citizenship, or both. Earlier, Charles Tilly (1986) noted much the same thing about collective action, that any general conceptualization would miss specific historically situated cultural repertoires likely to be consequential.

- Issue #2: A genealogical approach acknowledges the cultural and historical relativity of language, but thereby problematizes identification of processes shared across different times and places. Thus, Foucault's (1965) study Madness and Civilization identifies historical shifts in how ‘madness’ has been construed, in relation to an historically emergent interest in distinguishing reason and unreason. Yet this sort of analysis is by its nature more historicist than sociological. Its focus on social constructions of categories positions analysis at one remove (at least!) from a wide variety of robust social phenomena that might be the object of comparative analysis between past and present.

- Issue #3: The fundamental distinction between ‘past’ and ‘present’ is based on a privileging of the objective time of the clock and calendar, and even in these terms, it is problematic as a binary division. Thus, participants in a 2008 session of the Social Science History Association annual meetings could not agree on how to answer the question ‘when does the present begin?’ More generally, Louis Althusser and Etienne Balibar (1970) have argued that seemingly objective time – of the clock and calendar – is an ideological construction that bifurcates history and sociology.

2.2 In the first solution, historical sociologists might seek to develop a universalistic set of concepts intended to describe aspects of social forms, processes, and mechanisms posited to be transhistorical, if successful, solving issue #1 (conceptual historicity), thereby rendering issue #2 (genealogical ontology) moot, and obliterating the distinction between past and present (issue #3). To practice sociohistorical inquiry predicated upon transhistorical concept formations would typically depend on employing deductive theory, and it holds out the promise of demonstrating empirical continuities and discontinuities across historical places and times, including the past and present (for the foundational program, see Kiser and Hechter 1991; and for a more recent discussion, Mahoney 2004). Certainly we should welcome such efforts. However, the record of the historical social sciences over the past half-century does not afford optimism that a comprehensive battery of transhistorical concepts can be established, or even that a partial array of concepts could be adequate to engaging the great sociohistorical questions about social formations and social change – specifically, the character and prospects of modern social formations. The key challenge confronting this approach is that a transhistorical analysis might fail to capture salient processes that slip through its conceptual screen.

2.3 In the second solution, we might simply learn to live with – and enjoy! – conditions of inquiry in which, as the British novelist L. P. Hartley once put it, ‘the past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.’ A broadly postmodern solution takes the ineffability of cultural and historical difference as the reason to forego efforts to conduct inquiry via any set of transhistorical concepts. Instead, in a prominent and iconic solution, genealogical inquiry deconstructs ontological formations of various social orders that have obtained historically. Past and present are connected by their alternative ontological constructions, and by temporally and genealogically sequential developments that produce differences and continuities. The most famous exemplar is Foucault's (1965) study in which he foreswore any effort to define madness (or some cognate concept) in theoretical terms, instead seeking to locate the historical moments in which shifts in social ontological constructions of madness occurred. A number of critics fretted that Foucault's work – and postmodern approaches to history more widely – end up eroding history as practice: not only are stable concepts unavailable to characterize phenomena such as European feudalism or the absolutist state, but time itself offers no cartesian matrix by which to chart the march of events (Hall 1999: 225-28). However, historical sociologists have recently produced compelling exemplars that demonstrate the promise of ontological deconstructionist inquiry for comparison (Steinmetz 2007) and for the study of historical change (Somers 2008).

2.4 The third solution, heretofore largely untried, is to deepen understandings of connections between past and present by problematizing the very distinction between the two, fundamentally rejecting the privileging of objective chronological time upon which it rests, long purported to provide ‘the’ time of history.

2.5 I pursue this third solution here by taking off from findings from my recent book, Apocalypse: From Antiquity to the Empire of Modernity (2009). As the book's subtitle indicates, Apocalypse offers a history of the apocalyptic in the longue durée, and in a way that connects the apocalyptic to its seeming antithesis – modernity. Studying the apocalypse, I submit, unexpectedly alters our terms for engaging in comparative and historical sociology more generally, and for understanding modernity. In effect, sketching two interconnected accounts – of the apocalyptic and of modernity – serves as an exemplar for displacing ‘the’ time of history with a phenomenological history of times in the plural, what might be called a ‘structural phenomenology of history’ that accounts for multiple historically emergent temporalities in relation to one another. This phenomenological history of times mirrors Althusser and Balibar's (1970) structuralist depiction of a manifold hybrid ensemble of temporalities. However, because phenomenological sociology centres analysis in meaningful social action, it affords a thicker account of temporal structurations than Althusser and Balibar could muster through marxism.

2.6 A phenomenological history of times addresses issue #1, of conceptual historicity, by embracing the use of ideal types. Following Max Weber, ideal typification operates on something of a sliding scale, moving from highly general formulations that can be applied across time and place (e.g., ‘open’ versus ‘closed’ social relationships) to highly specific formulations (e.g., caesaropapism) that typify particular culturally conventional social constructions of the social and its processes. In turn, because this approach to concept formation is based in – inherently temporal – meaningful action, it offers the opportunity to offer the sort of phenomenological genealogy of social ontologies promised in the second solution, but without reducing historical and comparative sociology to postmodern historicism.

2.7 These might seem arcane epistemological considerations that sidetrack comparative and historical sociology from its important and enduring concerns with making sense of modernity. But epistemological issues matter. Let us recall the great self-reflexive leap forward that came in the 1980s. Theda Skocpol and Margaret Somers (1980; Skocpol 1984) proposed a typology of three alternative practices of sociohistorical inquiry. Around the same time, Charles Tilly proposed his agenda for looking at Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons (1984). Ironically, as the editors of the recent volume Remaking Modernity, Julia Adams, Elisabeth Clemens, and Ann Orloff (2005), tell us, at the early-1980s moment of methodological self-reflection, a ‘third wave’ of sociohistorical inquiry was beginning to take shape. If the first wave encompassed work of the likes of (the early) Charles Tilly, Reinhard Bendix, and Barrington Moore, a second wave emerged, beginning in the 1970s, strongly shaped by a rejection of ahistorical sociology and an embrace of the ‘big’ issues of political economy, revolution, industrialization, and state formation. The third wave comprises multiple intellectual currents – the cultural turn, the collapse of metanarrative, the explosion of topics of analysis, sources of data, and methodologies of analysis, and the proliferation of multiple analytic frames – from rational-choice theory to network analysis, and on to feminism and postcolonial thought. Given these crosscurrents, the third wave breaks onto shore in considerably choppier and more complex ways than the first and second ones.

2.8 In retrospect, the proliferation of approaches and topics beginning in the 1980s is striking for how much it shares Charles Tilly's rejection of ‘pernicious postulates’ in Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons. After all, Tilly brought into question the basic scientistic and positivistic assumptions upon which much of sociology, including historical and comparative sociology to that point, had been based – symptomatically, the postulate that presumes ‘society’ to be a relatively definable ‘thing’ with discernible boundaries, to be treated as an analytic object or ‘case’ through use of the comparative method. How to proceed under new intellectual conditions was the postpositivist challenge to which practitioners in the third wave responded.

2.9 In Big Structures..., Tilly also illustrated the pitfalls of attempting universal (or what he called ‘total’) history. To do so, he explored the difficulties that Fernand Braudel encountered in his efforts at total history. Tilly went out of his way to leave room for ‘individualizing’ studies – of one instance of a single social form – and he emphasized the need for research to be ‘historically grounded.’ However, even though Tilly ‘believe[d] passionately in getting the microhistory right in order to understand the macrohistory,’ and despite the difficulties posed by the project of ‘total history,’ his clear interest was in promoting ‘macrohistory’ rather than ‘microhistory.’ Pulling back from total history, Tilly made ‘the case for huge (but not stupendous) comparisons’ (1984: 74).

2.10 A little over two decades later, the editors of Remaking Modernity were quite clear on the point that various critical developments in scholarship, notably, postcolonial inquiry and its ‘provincialization’ of ‘the West,’ could yield broader critiques of the kinds of world history sometimes embedded in classical sociology (Adams, Clemens, and Orloff 2005: 60-1). Yet Adams, Clemens, and Orloff may have overstated the case when they argued that ‘meta-narrative and synoptic grand theory are making a comeback.’ The only exemplar they cited is the work of S.N. Eisenstadt on axial civilizations. They then commented, ‘This move toward grand civilizational narratives is part of a more general intellectual impulse, we believe, and a thoroughly understandable reaction to academic dispersion and global religious resurgence.’ Nevertheless, the editors were quick to acknowledge, ‘There are far too many open questions of theory and method in historical sociology ... that cannot be readily folded into a new totalizing narrative. At least, not yet!’ (Eisenstadt 2005:61; Adams, Clemens, and Orloff 2005: 61). If not yet, we may ask, when? And how?

2.11 Contemporary historical (might I say ‘apocalyptic’?) challenges, I submit, mean that we can no longer rely on modern social theory or conventional historical and comparative methodologies. We need a fresh start that avoids complacently employing conventional modern lenses. Eisenstadt's thesis of ‘multiple modernities’ (Eisenstadt 1999) acknowledges that there is no single telos of modernity. Indeed, any such assumption is now empirically in doubt. If we follow Eisenstadt, we need to avoid any ‘totalizing’ assumption that ‘Modernity’ constitutes a coherent whole. His analysis is important because it raises the next questions – how are the various social formations through which modernity operates structured, in themselves and in relation to each other? How might we conceive of the overall field of the social under the sign of modernity? Unfortunately, on these questions, Eisenstadt's comparative substantive analyses of world regions do not yield answers. Similarly, for all the attention to ‘globalization,’ the term remains something of a promissory note for some more deeply specified theorization of history yet to come.

2.12 The fundamental problem is this: despite compelling needs to make sense of our present historical moment, its sources in past historical developments, and its possibilities, our intellectual sensibilities make us suspicious of metanarrative – rightly, in my view. Yet, without metanarrative, broad historical accounts can have an ad hoc quality to them, lacking in sociological imagination. However much we might hope to reassert historical and comparative sociology's ‘historic role’ of making sense of history via ‘huge comparisons,’ in the long run, and in ways that have situational value for our sociohistorical moment, modernist methodologies and epistemologies have exhausted their capacities. It is this circumstance that I am seeking to transcend in my research on the apocalyptic in the long run through solution #3, by deconstructing our conventional ideas of historical temporality, past and present.

2.13 The questions of whether and how the apocalyptic and modernity are historically connected are vexing. On the one hand, apocalyptic moments seem like episodic eruptions that lack any long-term developmental history. On the other hand, there are substantial quasi-religious temptations to fall back on grand metanarratives – either of modernity's triumph or of jeremiad. Moreover, the apocalyptic is conventionally taken as antithetical to modernity, and really, beyond the orb of serious attention to issues of long-term modern historical development. Precisely for these reasons, then, considering the apocalyptic in relation to modernity over the long run poses challenges that, if resolved, may yield a novel solution of more general relevance to the problem of connecting past and present.

2.14 A ‘phenomenology of history’ offers a strategy for studying the apocalyptic and modernity via solution #3. The term itself is daunting, and it has a deep genealogy, most notably, in the pathbreaking efforts of Wilhelm Dilthey (1976) to draw history and biography into conjuncture, in the effort of Edmund Husserl toward the end of his life to reconcile transcendental phenomenology with historicity (1970; see also Carr 1974), and in Martin Heidigger's phenomenological exploration of temporality as a basis for approaching history as such ‘before scientific inquiry’ (Heidigger 2008: 2, orig. emph.). There have been important recent discussions about such a program and what it might mean (Carr 2001; Tymieniecka 2006). Moreover, historians and historical sociologists have increasingly found common ground with phenomenology in their efforts to capture the character of everyday experience (see, for example, Michel de Certeau 1984, 1988). However, the philosophical discussions of how a phenomenology of history might be implemented have not to my knowledge been matched by full-fledged macro-comparative histories of the sort that Tilly called for. The reasons are tied to the complex depth and richness of the phenomenological issues at stake in any such endeavour, and to the radical difference between any of a variety of phenomenological strategies and most of the conventional approaches to history on offer. Simply put, any phenomenological approach would require a dramatic shift in how we think about history. The approach to a phenomenology of history that I pursue here, a ‘social phenomenology,’ does not seek pure essences. Rather, it works to identify the basic ways in which each of us is situated in the ‘lifeworld’ – the everyday realm of the temporally unfolding here-and-now within which we live our lives, connecting to other people and media, social groups and institutions, culture and history (Schutz 1967; Schutz and Luckmann 1973). By addressing how alternative social temporalities become elaborated in the here-and-now, social phenomenology moves away from the conventional modern assumption that there is one, objective world time. Inevitably, it thereby disrupts any ordinary reduction of ‘history’ to a set of sequenced events and interwoven processes located on a line of past objective time. Thus, a broader phenomenological ‘history of times’ enriches the narrower ‘time of history’ (Hall 1980).

2.15 With this approach, we can consider how manifestations of the apocalyptic (along with other seemingly alien, non-modern social forms) articulate with diverse modernizing developments. My hope is that exploring this long-run history of the apocalyptic within a single sociological analysis will yield understandings that elude more focused studies. The very scope of this survey may seem reminiscent of earlier and now discredited ‘grand theories,’ ‘total history’ in Tilly's sense, or ‘universal histories.’ But the stakes are quite different than those of modernist grand theory or universal history, for I do not aim to study history in the long run from some putatively objective ‘view from nowhere.’ Instead, I develop an explicit theoretical typology to be employed in analyzing the apocalyptic in relation to modernity. I then sketch two ‘passes’ at a phenomenology of history, first, tracing decisive manifestations of the apocalyptic over historical time, then, turning to a temporal phenomenology of modernity.

Time / apocalypse / history

3.1 To understand either the apocalyptic or modernity in a new, phenomenological way first depends on theorizing their forms of social temporality. This in itself is a challenge: today even historical sociologists are so used to privileging modern, objective time that it is difficult to break out of this mindset. Tilly (1984: 14) was right to insist on ‘recognizing from the outset that time matters.’ Yet for him, the time that matters is objective time, which he described as a sequence of points. As Tilly wrote, ‘when things happen within a sequence affects how they happen.... Outcomes at a given point in time constrain possible outcomes at later points in time.’ Yet this important point – and the temporal objectivism that it reflects – should not be allowed to prevent us from coming to a deeper understanding of how the social is temporally constituted. Indeed, there have long been rich and diverse veins of scholarship concerned with social temporality (for two contrasting approaches, see Ricoeur 1984, 1985, 1988; Zerubavel 1979, 1981).3.2 In phenomenological terms, the most diverse social realms of activity – bureaucracy, work, worship, play, war, and shopping, for example – are constituted by how people collectively orchestrate and negotiate the multiple horizons and always unfolding mix of temporally structured meaningful social actions – in the vivid present, in anticipation of the future, and in meaningful remembrance of past events. When we consider social life in these terms, phenomenology shifts our attention from events and processes ‘in’ time toward sometimes intersecting, sometimes relatively autonomous social temporalities of life. By the same token, ‘history’ no longer amounts to a web of events linked on an objective temporal grid, as Annales School historian Fernand Braudel posited; historical events themselves have to be considered in their socially constituted temporalities (Hall 1980). This ‘phenomenological turn’ provides a distinctive way to reconceptualize social processes as diverse as class formation, economic activity, politics, and social movements.

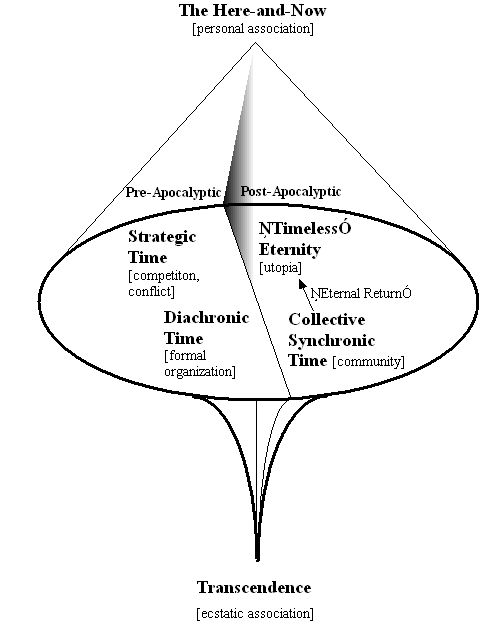

3.3 To chart developments of the apocalyptic and modernity in phenomenological terms and in the long run, I proceed by way of reference to six types of social temporality.[1]

- 1. The most straightforward situation we can imagine involves meanings that are completely contained in the here-and-now. Action does not reference events ‘outside’ the horizon of the unfolding moment. But life is rarely if ever so simple.

- 2. Collective synchronic time ritually organizes ‘sacred’ meanings designed to guide action. Traditions, memories, precedents, ‘the old ways’ of doing things, habits – all these create the here-and-now – even when oriented to the future – as a presumed replication, reenactment, or commemoration of the past.

- 3. Diachronic time uses rational and objective unit durations of time – seconds, hours, days, weeks, and so on –to provide a constructed framework for coordinating social action and scheduling and commodifying activities, most notably, labour.

- 4. Historically oriented strategic time orients toward intercontingent sequences. People make meanings in relation to events prior to the present that yield emergent conditions upon which people act in the vivid present to try to influence contingent outcomes and thus advance future attainment of goals. When action is oriented to anticipation of ‘the End,’ strategic time becomes pre-apocalyptic.

- 5. Post-apocalyptic temporality is strongly inflected with utopian meanings, for apocalypticists, centred on constructing a tableau the social in a New Era, either a heavenly one or a ‘timeless eternity‘ on earth, which is approached from a different direction through tradition that seeks a ‘return’ to a ‘golden age.’

- 6. Finally, transcendence encompasses the various ways that the world of everyday experience and the conventional institutional structures of society may fall away or be ‘bracketed,’ making absolute present time available to be experienced as ‘eternal.’

3.4 This ensemble of possibilities yields a typology that models alternative yet interconnected social temporalities (see figure 1).

| Figure 1. A general model of meaningful social temporalities that structure the vivid present with associated typical forms of social interaction in brackets |

|

I invoke these types of temporality in a neo-kantian way – as benchmark reference points – not by asserting some sort of straightforward ‘correspondence’ to social phenomena. Independent of this or any other social theoretical conceptualization, temporal possibilities have their own histories, and as we will see, the often nuanced, hybrid, and overlapping complexities of historically specific lived temporal enactments cannot be reduced to the six ideal types. All the same, as figure 1 asserts, alternative basic patterns of social interaction and organization can be identified in relation to the six types, suggesting a degree of face validity. The time through which bureaucracy operates, for example, is radically different from the time experienced within a community, different again from the time of war. Moreover, the typology can be used to tease out the complex meaningful structures of more elaborated temporal social forms – both in relation to a single type (e.g., different constructions of apocalyptic temporality) and as hybrids (e.g., tradition mapped in the objective time of a ritual calendar).

3.5 Apocalyptic times, eruptions that they are, arise in relation to diverse other kinds of social time: the here-and-now, the time of the calendar and clock, and other social elaborations of time – history (itself an invention of social self-understanding), strategic time, ecstatic experiences of ‘eternity,’ and so forth. Thus, piecing together how different kinds of social time emerge and become interrelated in different historical epochs yields a first pass at a phenomenology of history. However, we have to suspect that many of the developments important to either modernity or the apocalyptic are discontinuous with one another: they do not have sequential histories in their own right. Lacking any reason to assume other than this non-linear circumstance, we can trace a genealogy of apocalyptic developments in relation to modernity by pursuing a ‘configurational history’ (Hall 1999: 216-20) that zeroes in on the most salient and decisive ‘structural’ shifts in structurations of alternative types of apocalyptic and other kinds of social temporality and their consequences over the long run.

A configurational history of the apocalyptic[2]

4.1 The rise of the apocalyptic traces to ancient Zoroastrianism, and to the great monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Zoroastrianism with its imagery of a battle between the Lord of Wisdom and the god of falsehood and disorder anticipated an ultimate victory of truth and light. The ancient Israelites developed a sense of historical destiny as Yahweh's chosen people, who, when challenged by subjugation under alien powers, formulated prophetic hopes for a dramatic reversal of collective fortune. Christians came to believe Jesus to be that messiah. However, Christian theology pushed in two sometimes intertwined directions – toward personal transcendence of history by connection to eternal salvation, potentially for all mankind, or toward alternative formulations of how and when the apocalypse would yield redemption of the faithful at the end of history. In turn, what we may call Islamic apocalyptic emerged independently of Jewish or Christian antecedents, as triumphalist holy war meant to bring ever more territory under theocratic rule committed to the fulfillment of Allah's purposes.4.2 Overall, with the formation of the three great monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – protean narrative possibilities of the apocalyptic yielded new ideas about the character of history. In turn, in what would become the West, in the second millennium C.E., historical and apocalyptic dynamics increasingly transpired in the context of emerging modern diachronic temporalities and the rationalized logics of action that accompany them. Five configurational shifts are notable.

4.3 First, beginning in the eleventh century, the Roman Church gained sufficient organizational capacity to begin a centuries-long apocalyptic triumphalist movement to establish the predominance of Christendom in relation to those whom it defined as Other – both externally via the Crusades against Muslim infidels, and internally against ‘heresy’ through regional crusades, the Inquisition, and religious pacification and conversion.

4.4 Second, in a social climate riven by hardship and calamity, the Crusades spread an ethos of apocalyptic fervour among the popular classes. This fervour became erratically mobilized via longstanding heterodoxical tendencies and Christian theological discourses that began to consolidate a generalized medieval template of the apocalyptic social movement. The most revolutionary of such movements promised an end to exploitation of the poor by landowners and the Church, and they fed the flames of peasant rebellions and small-scale holy wars, which feudal powers allied with the Church duly suppressed.

4.5 The third configurational shift, during the Reformation, emerged when some secular authorities cast their lot with religious reform movements, in part to forestall the success of even more radical apocalyptic movements. There were dual consequences. On the one hand, national Reformation movements themselves often took on an apocalyptic aura, as a struggle against Rome as ‘the Beast.’ On the other hand, in Catholic as well as Protestant countries, the state took over the previously religious function of regulating religious legitimacy within its borders, thereby largely containing, pacifying, and ultimately undermining the apocalyptic within societies increasingly oriented toward ‘modernizing’ personal discipline and social order. The notable exception in the West was the United States, where millennialism continued to flourish under modernizing conditions.

4.6 Fourth, in the wake of modernizing containment and pacification, the motifs of apocalyptic war became relocated from the lineages of religious apocalyptic, and into the sphere of secular politics – in particular, quasi-sacred nationalist, anticolonial, and anticapitalist movements. The most significant development was the fusion of apocalyptic war with diachronic discipline, strategic temporality, and technologies of modern warfare, yielding apocalyptic insurgent strategies ranging from anarchists' terrorist ‘propaganda of the deed’ to guerrilla warfare.

4.7 Fifth, the collapse of the Soviet Union meant the eclipse of communism as a global secular-apocalyptic movement, and the end of its support for anticapitalist nationalist struggles, especially in underdeveloped and developing countries. Modernity had raised the secular apocalyptic to a global level. However, the ascendency of modernizing projects had not brought the death of God and the end of religion, least of all in apocalyptic domains. Instead, at the end of the twentieth century, al Qaida and its allies shifted Islamic jihad from nationalist struggles against the ‘nearest enemy’ to a global struggle against the ‘far enemy,’ embodied in the United States. In turn, the Bush administration took the occasion of the 9/11 attacks to launch a multipronged countermovement against a so-called ‘axis of evil.’ Apocalyptic war unfolded in a symmetric if not always explicit fashion, and it came to occupy the ideological space previously taken up by the secular yet apocalyptic Cold War.

4.8 Overall, the possibilities of the apocalyptic have traversed a bridge across modernity. After a long series of developments in the realm of religious politics at fateful times, during the eighteenth century, the apocalypse became secularized. Today, at the beginning of the third millennium of the Common Era, it is being reconstituted in a new way, ambiguously sacred and secular. The curtains have parted on a new and unprecedented globalized epoch of apocalyptic violence. We have reached a truly ‘postmodern’ moment – not just the cultural one announced by literary theorists and deconstructive philosophers during the last decades of the second millennium, heralded by the triumph of relativity, the eclipse of Reason, and the decline of objective, non-instrumental science. Beyond those developments, we may now be undergoing an epochal shift away from understanding history as the march of progress driven by the bundled development of science and democracy. Today, apocalyptic religious violence portends a new structuring of the world order, a new, postmodern apocalyptic epoch, the form of which remains as yet open to the play of events.

Apocalyptic times and modern times

5.1 The configurational history of the apocalyptic in the west that I have just sketched spans a long period of objective time. However, focusing solely on objective time is an impediment to understanding either the apocalyptic (as we have seen, itself encompassing multiple possible temporalities) or modernity. Instead, a historical phenomenology of multiple temporalities sets certain markers along a pathway toward describing modernity itself as what Elisabeth Clemens (2007) calls a ‘recomposition’ – a temporal hybrid that I have described as the Empire of Modernity (Hall 2009: chap. 5). Thinking about modernity as a complex hybrid of multiple and overlapping temporal forms of action can displace the simplistic binaries of modernity and tradition, advanced and underdeveloped society. Such recognition of the multiple temporalities in play under the sign of modernity offers a way of transcending the radical opposition in social theory between accounts of administrative legal-rational modernity versus accounts of the strategic conflicts of imperialism as bases of social order. Most centrally, the ‘Empire of Modernity’ has developed through a centuries-long series of projects and initiatives centred in the interacting diachronic time of modernity and strategic time of empire. The shape and span of the resulting social order are plastic and subject to myriad institutional patterns, new formulations, and reconstructions. Three brief sketches begin to show how an historical phenomenology can reframe a series of modern theoretical conundrums by displaying them in relation to the interplay of temporally constituted social forms.The diachronic axis of modernity

5.2 To begin with, as Peter Wagner (1984) argued, modern society depends upon forms of ‘discipline’ that order social activity, but simultaneously must orchestrate conditions of ‘liberty’ that underwrite the potential of individuals to act autonomously in pursuing their own interests – albeit in socially appropriate ways. Essentially, modern disciplining emanates from the realm of diachronically organized action.

5.3 In figure 1, I characterized diachronic temporality as the medium of social action organized along legal and rational lines, in which the flow of events becomes subject to routinization and calculation. Here, if Weber's sociology of legal-rational authority is restricted to considering the state, bureaucracy, and legitimacy, its focus is too narrow. Weber's legal-rational typification must instead be understood to extend the legitimate exercise of power outward to the entire range of diachronic operations in the social. In this, it merges seamlessly with Michel Foucault's argument that governmentality is diffuse in its exercise. The diachronic is not just about power and bureaucracy; more broadly, it encompasses the ordering and coordination of social activity in any domain.

5.4 In these terms, the diachronic is emergent, not fixed (Whitrow 1988: chap. 10; 181-82). It encompasses the ever more precise measurement of duration and the ‘disembedding’ of units of time that can be moved around on schedules (Lash and Urry 1994: 229). Because diachronic time makes possible the projection of alternative future events, it puts into play the planning of the future, such that any given present is no longer simply a ‘here and now,’ but also, the realization of a (past) projected future and the anticipation of events to come, already plugged into diachronic schedules.

5.5 Because diachronic time itself undergoes development (Luhmann 1982: 284-86), we continue to witness ever novel constructions of the diachronic that underwrite ever novel integrations of technology and ‘nature’ across divergent spheres of lifeworldly social activities. This expansion transpires through the differentiation of multiple diachronic worlds – quintessentially of government agencies, business corporations, and increasingly, diachronically centred social-movement organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Each has its: distinctive temporal horizons; administrative arrangements; opportunities of power by way of legitimacy, decrees, laws, patents, property rights, and popular support or acquiescence; claims of jurisdictional span for goal-oriented operations of administration and policing; and capacities of resource mobilization. In the world where diachronic temporality predominates, social systems both proliferate within organizations interfacing with their environments, and differentiate in relation to one another. Thus, the diachronic world emblematic of modernity is not ‘the’ system, but a pluralized welter of interconnected, overlapping, and sometimes contradictory ‘systems’ (Luhmann 1982)

5.6 Among diverse channels carrying the spread of the diachronic, surely one of the most significant has involved multiple and emergent relationships with strategic temporalities. On this front, operations within diachronic rational bureaucracy have subordinated legitimate exercise of strategic violence to administrative (and judicial) regulation. The upshot is (incomplete) diachronic organization, administration, and regulation of how strategic violence is deployed in contending nation-state territorial empires, in interstate war, and in the broader supra-national governmentality of the Empire of Modernity. Along a different channel, diachronic governmentality has extended operations and regulative frameworks to bring various kinds of order to zones of temporally strategic lifeworldly activity that previously lay beyond its effective policing – from crime and non-legitimate violence, to the play of strategic action in economic activities such as ‘markets.’

5.7 The interfaces, disjunctures, and aporias between the diachronic and synchronic temporalities are quite different. Here, Habermas's theory of lifeworld colonization and Foucault's model of governmentality describe an overall dynamic in which diachronically organized action is undertaken to organize the here-and-now according to goals external to the social actors who are the object of its organization and discipline. The operations of colonization and governmentality toward the lifeworld are diverse. They encompass not only education, labour market regulation, social welfare administration, health services, and the like, but also policing of families and sexuality, and the mediated permeation of lifeworlds through popular entertainment, marketing and advertising, mass media and the internet, the orchestration of consumption and leisure (and consumption as leisure), and the design of social lifeworldly spaces that Baudrillard dubbed ‘simulacra’ (such as shopping malls, fast-food restaurants, and tourist destinations) to mimic the imaginaries of consumer desire (Hall, Neitz, and Battani 2003). People acting in the here-and-now thus routinely interface with external diachronically-ordered systems and agents of governmentality as we move through daily life.

Democracy and the diachronic

5.8 For all the power and seeming pervasiveness of diachronic colonization and governmentality, their capture of the social is inherently incomplete. Rationalization, Max Weber already understood at the beginning of the twentieth century, has its limits (Roth 1987). Phenomenologically, it thus becomes possible to locate a series of puzzles concerning modernity's empire in temporal terms. Just to list them is to suggest future tasks of inquiry.

5.9 Collapsing the categories of Habermas and Foucault, historical and comparative sociology should consider systemic governmentality in relation to politics – an enterprise centered in strategic temporalities. Here, the distinction between ‘democracy’ and ‘dictatorship’ sets up a false opposition, used by Francis Fukuyama and others to assert a supposed inherent elective affinity between democracy and capitalism. However, once we acknowledge the complex webs of systemic governmentality across zones of temporality, more complex issues must be addressed: (1) whether, how, and in what social and spatial regions, the Empire of Modernity fosters or regulates ‘liberty’; (2) the ways and means by which democratic versus other kinds of political power ‘contain’ and direct administrative and corporate governmentalities; and (3) whether individuals, subcultural communities, and social strata that form around recognition of shared interests regard prevailing systemic governmentality as legitimate, or whether they coalesce into a social movement of opposition – including those that take some apocalyptic or other countercultural direction.

5.10 People generally find democracy attractive, but it is a fragile hybrid that connects the diachronic realm of governing routines and procedures with both communities and the civil society of individuals in free association with one another. Under emergent conditions of globalization, as the transformative departures from state communism in Russia and China demonstrate, democratic processes versus alternative kinds of administrative and corporate power remain open to ever novel reconstructions. More generally, the devolution of national sovereignty into multiple, often overlapping sub- and super-national jurisdictions only differentiates the possibilities of governmentality. On an entirely different front, capitalism increasingly has substituted privately owned quasi-public spaces (e.g., shopping malls, vacation destinations) for public spaces, yielding a proliferation of private sovereignties to which the consuming public is subject. The overall consequences are clear. Democracy is not the ultimate basis of power even in democracies, nor is it inherent to modern nation-state formation. Instead, democracy comes into play at specific sites and nexuses within nested and overlapping complexes of systemic governmentality that are not inherently democratic. Law, regulation, policy, and ‘best practices’ rather than representative government per se are the operative principles of diachronic governmentality in the Empire of Modernity.

Diachrony and community

5.11 The play of the diachronic also spills beyond strategic politics narrowly construed, into domains of synchronic communities. Like the lifeworld here-and-now, synchronic communities remain strongly resistant to diachronic colonization. The persistence of communities embodies the enduring potential for collective organization in relation to communally experienced social aspirations, and it is thus a central though fragile institutional locus of modern life that establishes a contretemps to thoroughgoing rationalization of the social order.

5.12 Collective synchronic temporality (see figure 1) is built upon an occasioned ritualization of communion underwritten by religious sacralization. Whether we follow Emile Durkheim (1995) or Mircea Eliade (1959), whether ritual reaffirms the sacredness of community itself or its traditions, group solidarity is enhanced by the ritualized delineation of boundaries – between the group and the Other, between the sacred and the profane. To be sure, with the postmodern efflorescence of ‘personal religion,’ ‘spirituality,’ and the drug culture, there has been an increase in freelance individual and self-forming group quests for spiritual transcendence in the eternal here-and-now, independent of formal religious organizations. Nevertheless, religious congregations have not disappeared. Outside Europe, they thrive in much of the world, and mediation of access to experiences of transcendence is still their stock-in-trade (Taylor 2007). In addition, paralleling religion, synchronic ritual-creating solidarity occurs in a wider range of communities, ethnic groups, nations (and political religions such as fascism that promote aesthetics of nationalism), lifestyle and cultural movements centred on special activities and experiences, social clubs, sports teams, and status groups of all kinds. Each offers individuals the potential for experience of catharsis linked to group identity and collective solidarity.

5.13 With the rise of modern, mass mediated culture, communities have increasingly become subject to organization via diachronic procedures of rationalization. Moreover, the synchronic solidarity-producing ritual that facilitates a collective state of nervous excitement – what Durkheim called effervescence – became a very early target of rationalization projects, notably in the Roman Church's medieval formulation of a mass-distributed liturgy and calendar of masses. By the twentieth century, fascist and communist political movements used highly ritualized mass rallies to manufacture the experience of solidarity. In turn, they filmed rallies, thus taking a major step in the direction of producing mediated simulations of synchronicity. Film, television, and the Internet, it has turned out, can substitute for the immediacy of synchronic ritual in the vivid present. In short, the collective synchronic is subject to rationalization and simulation in its orchestration. Its basic ritual mechanism that produces solidarity is not of modernity, but it persists within modernity.

5.14 As we now know, modernity did not end the salience of race, ethnicity, community, religion, or nation as bases of identity and solidarity. Whereas mid-twentieth century theorists envisioned a world of equal rights among individuals, later theorists increasingly grappled with the question of how societies could balance equality among individuals with the politics of recognition of identities affirmed on the basis of group membership – especially ethnic identities, gender identities, and religious identities (see, e.g., Fraser 1997) – and how the state can or should recognize or delimit the rights of various communities of solidarity (Alexander 2006; Fraser 2000).

5.15 Overall, a structural phenomenology of history reveals the Empire of Modernity as a hybrid (re-)composition of social activities unfolding within and across multiple fields of temporality. The implications concerning religion resonate more generally. The diachronic institutions that project modernity are vehicles of secularization. However, diachrony can never subsume either the here-and-now or the collective synchronic temporality of the community. In particular, although synchronic ritualizations of sacred versus profane may be orchestrated by way of diachronic temporality (for example, via the mass media), the core logic of ritual is synchronic. Simply put, the diachronic does not do ritual. Thus, although the diachronic can provide a way of life that either does not entail community or, more likely, organizes the conditions under which subcultural communities exist, short of administratively organized, highly politicized, quasi-religious nationalism, it cannot offer a compelling basis of social organization that substitutes for community or addresses ‘religious’ aspirations of individuals.

Conclusion

6.1 Looking at the apocalyptic in the long run and in relation to modernity suggests a new way of understanding the relation between past and present, and a new practice of comparative/historical sociology. Rather than essentializing modernity as a totality conceptually divided off from ‘the past,’ there has been a movement in recent years toward recognizing what Eisenstadt has dubbed ‘multiple modernities.’ Yet to date these developments have been more programmatic than substantive, in part because they have lacked any clear basis to resolve the three general comparative and historical issues that I sketched at the outset – (1) conceptual historicity, (2) genealogical ontology, and (3) the ideological construction of temporality.6.2 We are called by our times to make sense of the present in relation to history. This mandate will be fulfilled by a genealogical approach only if it does not result in a postmodern historicism or history in fragments. Yet, conversely, as Tilly observed, we are in no position to offer a total history – what others call universal history. Nor, finally, can transhistorical concept formation unlock the puzzles of historical development insofar as it masks the ontological and existential specificity of historical formations.

6.3 The alternative that I have explored here – what I have described as a phenomenology of history – has two components. First, to transcend the dilemma posed by the problems of conceptual historicity and genealogical ontology, but without succumbing to either naïve postpositivist realism or postmodern historicism, I have followed Max Weber's historical methodology connected to concept formation by use of ideal types, thereby deploying concepts along a sliding scale of historicity. In my substantive analysis, I have thus sought to recognize both the generic, transhistorical possibilities of the apocalyptic and to chart their historical and cultural instantiations. Because Weber's comparative and historical verstehende Soziologie is fundamentally centered on the interpretation of meaningful action and complexes thereof, and because meaningful action always entails one or another orientation toward and construction of temporality, this component of the approach dovetails with the second one – the tracing of historical developments and forms of action and organization in relation to social temporalities. In these terms, the present essay has described both a configurational genealogy of the apocalyptic and its ‘recompositions’ in relation to modernity. Further, I have sketched some of the ways in which modernity itself can be characterized as a complex of interacting social forms, each with its own distinctive construction of social temporality. These analyses suggest that, prior to pursuing ‘causal’ analysis or ‘explanation,’ historical sociologists can begin to describe social phenomena in ways less encumbered with ontological and epistemological legacies of the binary of positivism / historicism, and do so on a basis that begins to fulfill Heidigger's desideratum of achieving a phenomenology of history – a description of historical developments of social forms and their interrelationships that offers a platform for sociohistorical inquiry.

6.4 In these terms, the apocalyptic, for example, cannot simply be relegated to treatment as a ‘variable’ that is ‘caused by’ or ‘explains’ (or fails to explain) other social phenomena – economic development, war, family structures, and so on. To the contrary, radically alternative forms of social enactment sometimes traffic in de facto apocalyptic questions of ultimate meaning. People make sense of their circumstances in various ways, and how people do so can be consequential for how events unfold. Such relationships between ideas, interests, and sociohistorical situation have been described before, by Max Weber in his famous railroad metaphor. After acknowledging that ‘material and ideal interests’ govern conduct, Weber remarked,

Yet very frequently the ‘world images’ that have been created by ‘ideas’ have, like switchmen, determined the tracks along which action has been pushed by the dynamic of interest. ‘From what’ and ‘for what’ one wished to be redeemed and, let us not forget, ‘could be’ redeemed, depended upon one's image of the world. (Weber 1946: 280).

6.5 Meaningful temporalities of enactment – not only apocalyptic ones, but also other intricately interwoven temporalities in the complex Empire of Modernity – do not ‘cause’ action, they set the alternative tracks of meaning along which social streams of events unfold.

6.6 The apocalyptic introjection of the sacred into history originated before modernity, but the apocalyptic became modern, and now, modernity has become apocalyptic. This basic relation of the apocalyptic to modernity encapsulates a more general point – that modernity is not simply a point or era in time, a ‘present’ that is connected to and diverges from ‘the past’ in this way or that. Rather, the modernity/empire complex is constituted through multiple and crosscutting relationships among social arenas of action that fundamentally diverge from one another in their temporal orders. This circumstance implies that there is no overall telos to modernity, that objective temporality will never completely absorb or subordinate fields of activity centrally ordered in alternative temporalities (e.g., of the here-and-now, or synchronic ritual, or apocalyptic war), and thus that the character of ‘modernity’ is indeterminate, and open to diverse alternative constructions that order multiple temporally organized social fields in radically different ways. By taking a phenomenological turn in historical inquiry, we find that there is no ‘present.’ But this seeming loss actually offers the opportunity for pursuing a new kind of configurational history, one that opens up the possibility of theorizing historical development in relation to multiple temporally ordered social fields and their relationships to one another.

6.7 Since the eclipse of high modernity, with the rise of postmodern skepticism, and especially in the wake of 9/11, liberal capitalist democracies have faced increasing cultural pessimism about the prospects of the modern vision, and defenders of that vision have offered increasingly beleaguered affirmations of it. The pessimism no doubt has real sources, and the affirmations are often heartfelt, but both partly derive from a myopic understanding of modernity born of viewing it through the lens of its (incompletely realized) program. Under these conditions, a pragmatic exploration borne of an altogether different viewpoint may not only reposition our understanding of the apocalyptic in relation to modernity, but in the bargain, recast our understandings of modernity itself.

Notes

1 These ideal types were originally formulated in my comparative study of contemporary utopian communal groups (Hall 1978), on the basis of a critique and extension of Karl Mannheim's (1937) temporal specification of four utopian mentalities. As I argued, Mannheim's four types depend on three alternative temporal accentuations of reality – synchronic, diachronic, and apocalyptic. In turn, a phenomenological supplement of Mannheim's types, I proposed, could be achieved by positing three alternative ‘social enactments’ or constructions of reality –the ‘natural attitude,’ institutionally or socially ‘produced’ constructions of reality, and ‘transcendence,’ which in the phenomenological sense, ideal typically ‘brackets’ any symbolic or cultural construction of reality. Analysis of countercultural communal groups demonstrated correlations between phenomenological constructions of time and social enactment, and characteristics of communal groups specified via more conventional weberian conceptualizations of meaningful patterns of social interaction, e.g., in relation to power and economic want satisfaction. On this analysis, basic patterns of social organization have distinctive temporal structurations. My subsequent analysis (Hall 2009) suggests that the ideal types originally specified for communal groups have wider application. Of course, as Weber (1978: 20) emphasized, all ideal types are only models, not descriptions of reality. For this reason, they cannot be assessed per se for validity, and what matters is their utility in sociological analysis.2 The following discussion draws on and elaborates sections from Hall (2009: chapter 7), with permission from the publisher. For details, and historical sources, see Hall (2009: chapters 2 - 6).

References

ADAMS, Julia, Elisabeth Clemens, and Ann Orloff. 2005. "Introduction: Social theory, modernity, and the three waves of historical sociology," in Julia Adams, Elisabeth Clemens, and Ann Orloff, eds., Remaking Modernity, pp. 1-72. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

ALEXANDER, Jeffrey. 2006. The Civil Sphere. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ALTHUSSER, Louis, and Etienne Balibar. 1970 (1968). Reading Capital. London: NLB.

BERGER, Peter. 1967. The Sacred Canopy. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

CARR, David. 1974. Phenomenology and the Problem of History: A Study of Husserl's Transcendental Phenomenology. Evanston, Il.: Northwestern University Press.

CARR, David. 2001. "On the phenomenology of history," in Steven Crowell, Lester Embree, and Samuel J. Julian, eds., The Reach of Reflection: Issues for Phenomenology's Second Century [electronic resource]. Boca Raton, Fl.: Center for Advanced Research in Phenomenology, Inc., Department of Philosophy, Florida Atlantic University, Electron Press.

CERTEAU, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley : University of California Press.

CERTEAU, Michel de. 1988 [1975]. The Writing of History. New York, N.Y.: Columbia University Press.

CLEMENS, Elisabeth S. 2007. "Afterword: Logics of history? Agency, multiplicity, and incoherence in the explanation of change," in Julia Adams, Elisabeth Clemens, and Ann Orloff, Remaking Modernity, pp. 493-515. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

DILTHEY, Wilhelm. 1976. Selected Writings, ed. and trans. H.P. Rickman. New York: Cambridge University Press.

DURKHEIM, Emile. 1995 (1915). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, translated with an introduction by Karen E. Fields. New York: Free Press.

EISENSTADT, S.N. 1999. "Multiple modernities in an age of globalization." Canadian Journal of Sociology 24: 283-295. [doi:10.2307/3341732]

ELIADE, Mircea. 1959 (1949). Cosmos and History: the Myth of the Eternal Return. New York: Harper & Row.

FOUCAULT, Michel. 1965. Madness and Civilization. New York: Pantheon.

FRASER, Nancy. 2000. "Rethinking recognition." New Left Review 3: 107-20.

FRASER, Nancy. 1997. "From redistribution to recognition?: Dilemmas of justice in a 'postsocialist' age," in Fraser, Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the "Postsocialist" Condition, pp. 11-39. London: Routledge.

HALL, John R. 1978. The Ways Out: Utopian Communal Groups in an Age of Babylon. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

HALL, John R. 1980. "The time of history and the history of times." History and Theory 19: 113-31. [doi:10.2307/2504794]

HALL, John R. 1999. Cultures of Inquiry: From Epistemology to Discourse in Sociohistorical Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. <http://www.cambridge.org/uk/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521642200>

HALL, John R. 2009. Apocalypse: From Antiquity to the Empire of Modernity. Cambridge, England: Polity. < http://www.polity.co.uk/book.asp?ref=9780745645087 >

HALL, John R., Mary Jo Neitz, and Marshall Battani. 2003. Sociology on Culture. London: Routledge. <http://www.routledge.com/books/Sociology-On-Culture-isbn9780415284851>

HEIDIGGER, Martin. 2008 (1927). History of the Concept of Time: Prolegomena. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

HUSSERL, Edmund. 1970. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Evanston, Il.: Northwestern University Press.

KISER, Edgar, and Michael Hechter. 1991. "The role of general theory in comparative-historical sociology." American Journal of Sociology 97: 1-30.

LASH, Scott, and John Urry. 1994. Economies of Signs and Space. London: Sage.

LUHMANN, Niklas. 1982. The Differentiation of Society. New York: Columbia University Press.

MAHONEY, James. 2004. "Revisiting general theory in historical sociology." Social Forces 83: 461-89.

MANNHEIM, Karl. 1937. Ideology and Utopia. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

RICOEUR, Paul. 1984, 1985, 1988. Time and Narrative, 3 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

ROTH, Guenther. 1987. "Rationalization in Max Weber's developmental history," in Scott Lash and Sam Whimster, eds., Max Weber, Rationality, and Modernity, pp. 75-91. London: Allen & Unwin.

SCHUTZ, Alfred. 1967 (1932). The Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston, IL.: Northwestern University Press.

SCHUTZ, Alfred, and Thomas Luckmann. 1973. The Structures of the Lifeworld. Evanston, I.L.: Northwestern University Press.

SKOCPOL, Theda.1984. "Emerging agendas and recurrent strategies in historical sociology," in Theda Skocpol , ed. Vision and Method in Historical Sociology, pp. 356-91, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SKOCPOL, Theda, and Margaret Somers. 1980. "The uses of comparative history in macrosocial inquiry." Comparative Studies in Society and History 22: 174-97.

SOMERS, Margaret. 1997. "Narrativity, narrative identity, and social action: rethinking English working-class formation." in John R. Hall, ed., Reworking Class, pp. 73-105. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

SOMERS, Margaret. 2008. Genealogies of Citizenship: Markets, Statelessness, and the Right to Have Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

STEINMETZ, George. 2007. The Devil's Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

TAYLOR, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

TILLY, Charles. 1984. Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

TILLY, Charles. 1986. "European violence and collective action since 1700." Social Research 53: 159-84.

TYMIENIECKA, Anna-Teresa., ed. 2006. Logos of History - Logos of Life, Historicity. Book 3 of Logos of Phenomenology and Phenomenology of the Logos. Analecta Husserliana 90.

WAGNER, Peter. 1994. A Sociology of Modernity: Liberty and Discipline. London: Routledge.

WEBER, Max. 1946 (1915). "The social psychology of the world religions," in H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills, eds., From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, pp. 267-301. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

WEBER, Max. 1978. Economy and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

WHITROW, Gerald J. 1988. Time in History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ZERUBAVEL, Eviatar. 1979. Patterns of Time in Hospital Life. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1979..

ZERUBAVEL, Eviatar. 1981. Hidden Rhythms: Schedules and Calendars in Social Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.