Sport in a Credit Crunched Consumer Culture

by John D. Horne

University of Central Lancashire

Sociological Research Online 14(2)7

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/2/7.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1920

Received: 27 Apr 2009 Accepted: 23 May 2009 Published: 31 May 2009

Abstract

This brief rapid response article suggests a few ways in which modern competitive sport and large-scale sport events have developed in line with the logic of (late) capitalist modernity. It considers the impact of the credit crunch for recent trends in sport and suggests that the sociological study of sport faces the same concerns as other sociological domains of interest during the current economic conditions whilst having its own specific public issues and private troubles to consider.

Keywords: Sport, Physical Activity, Credit Crunch, Capitalism, Consumer Culture

Introduction

1.1 At the end of the first decade of the 21st century we are faced with a new political environment in the midst of an old type of economic crisis. The financial system that helped fuel the consumer culture of the past 25 years is in chaos. Yet recession, deflation, rising unemployment, declining purchasing power, were all features of the environment for sport and leisure in capitalist Britain surveyed in the early 1980s (e.g. see Clarke & Critcher, 1985). The impact of the current socio-economic situation on specific social groups and their responses to it are as of much interest today as they were a quarter of a century ago. In this rapid response article therefore we consider the impact of the credit crunch for recent trends in sport.1.2 Our argument is as follows. Many of the apparently "fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions" in sport, as in much else, have been undermined in the past 25 years (Marx & Engels 1969 [1848] p. 46). The current recession will heighten market-driven changes that have impacted on sport, especially professional sport. Yet in this economic context the place of sport in people's lives will continue to exhibit the paradoxes of life in consumer culture. Sport may be seen as a means of resisting as well as subscribing to these conditions. Much contemporary sport is both a product of an alienating system of production on which we depend, and yet also offers us the raw materials for creating our own sense of ourselves (Horne 2006 p. 165).

The credit crunch meets the sponsorship squeeze:

2.1 Writing shortly after the Hillsborough football disaster in 1989 the late Ian Taylor identified six features of the state of football in England (Taylor, 1989). Football grounds were treated as shrines by fans, and they still acted as an emblem of locality for them. However aspects of what Taylor was later to call 'market football' were undergoing re-development. Then the sport was beginning to be discussed by politicians and administrators using the rhetoric of modernization and normalization, whilst it was still pervaded with violence and the theme of disaster. Market football has prospered in the twenty years since with regular coverage of the excesses that massively increased revenues from broadcasting and sponsorship have brought. The vast salaries, exploits and lifestyles of top-flight players in the English Premier League (EPL) are regular features of the news, celebrity and entertainment pages as much as the sports pages. Yet in the current economic circumstances with reduced attendances, sponsors and advertisers cutting back on their marketing budgets and broadcasters having less discretionary money to invest, it is likely that news of the indebtedness of clubs, especially in the lower leagues, will also start to appear with more frequency. Small clubs, and leagues in smaller societies such as Scotland, are most vulnerable in these circumstances, although it is already apparent that there will be few billionaires prepared to bail out bigger clubs. New building projects are likely to be put on hold and excessive salaries will either come down or be subject to a form of capping, as exists in rugby union.2.2 In 2008 Tiger Woods lost his sponsorship with the US car manufacturer Buick, Johnson & Johnson, Kodak, ManuLife and Lenovo all withdrew from sponsoring the International Olympic Committee (IOC) through its TOP (The Olympic Partnership) Program, and some people expected 'US Treasury' to replace the logo for insurance company AIG on the shirts of Manchester United when the company received billions of dollars from the US Government. Early in 2009 AIG formally announced that it was quitting as Manchester United's shirt sponsor. If some of the most marketable athletes, teams and organizations in the world are finding sponsorship sources difficult to sustain, it is understandable why some see the corollary of the credit crunch for sport as the sponsorship squeeze. In such a climate it is likely that events based sports – such as golf and tennis - will shrink their schedules. Marginal, what might be called 'relevance challenged', events will wither away. Teams in successful events will either fold altogether (such as Honda did in Formula One (F1) motor racing to be replaced by the Brawn team) or need to seek new sponsors, such as the English cricket team whose sponsor Vodafone announced it would not renew after January 2010.

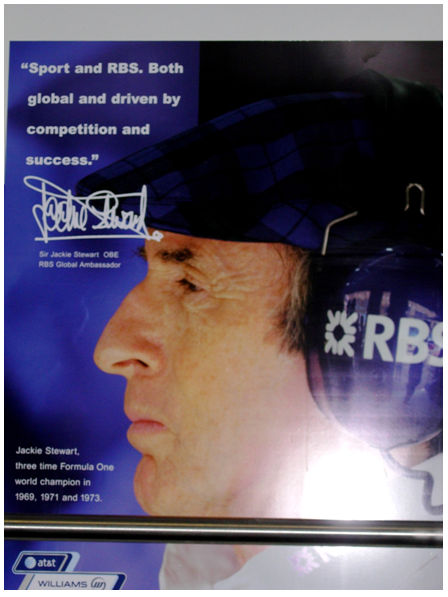

2.3 There will remain some anomalies. At the end of the week in which the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) recorded the biggest loss in British corporate history (£28 billion) journalist Simon Hattenstone (2009) encountered something unexpected when he arrived at Edinburgh airport:

Every wall is plastered blue and white with RBS logos and sponsorships. "Sport and RBS. Both global and driven by competition and success," Sir Jackie Stewart, RBS global ambassador and three times formula one world champion, tells me in one ad. "The principles behind sporting success an (sic) business success are identical" Jack Nicklaus, RBS ambassador and golfing legend, tells me in another (Hattenstone 2009 p. 28).The advertisements were still there in April 2009 (see image 1) and despite gaining substantial support from the UK taxpayer in order to remain in business the bank also found time to agree an extension to its deal to sponsor the Six Nations rugby union championship in November 2008.

|

2.4 Other means to obtain wider media exposure and hence sponsorship funding usually reserved for the more televisual sports, such as football, rugby, tennis, and F1, include moves to attract sponsorship and audience interest in the Far and Middle East, and to create shortened versions of sports and sports events. Time is a crucial feature of sport for the media, after visual attractiveness and simplicity of rules, as we will see in the next section.

Express yourself – faster: the changing format of sport and its relationship to the mass media

3.1 The sport media industry is at a crossroads as the global economic crisis impacts on media companies, slowing revenue growth and narrowing profit margins. As Owen Gibson of The Guardian writes, "neither Pay-TV nor the sports rights market has ever known a recession" (Gibson 2009a, p. 6; see also Gibson 2009b). This will make them more concerned to select the most attractive sports to cover. As we have noted even the top tier of sports competitions, such as the EPL and the IOC, face a sponsorship squeeze. In the UK with respect to broadcasting deals the leading sports, cricket, rugby, tennis and track and field athletics, have recently agreed medium term deals that should see them out of the current negative economic situation. That EPL football is looking to expand its coverage and revenues, from a previous deal worth £1.7 billion over three years, when it receives bids for broadcasting rights from 2010 onward is indicative of the rule, in the UK at least, that rights for coverage of football are in a different league than those for other sports. Yet broadcasters are still likely to want to have, and get, more say in the scheduling, structure and marketing of the sports they cover. Hence sports and events that have the ability and share the ambitions of broadcasters more closely, to build global audiences in order to offset the impact of domestic conditions, are likely to be the most wanted. In the UK whilst ITV and pay-TV company Setanta began coverage of the English FA Cup competition in 2008, ITV announced that it would not be renewing its coverage of the Oxford and Cambridge boat race and F1 racing.3.2 Another way in which television will drive the development of sport is the move toward faster, spectacular, entertainment, through the packaging and presentation of events for audiences with short attention spans. Hence there has been the creation of new forms of 'express sport', shortened versions of sports such as golf, tennis, squash, eventing and most spectacularly cricket.

3.3 Mike Selvey (27 October 2008, p. 10) writing in The Guardian referred to Twenty20 as cricket's "dot.com" boom; an economic bubble that is likely to explode after making some people, including a few players, very wealthy. Twenty20 is fast, 20 overs per side, which means that matches can be finished in a few hours in an evening, and/or several matches can be played on the same day. Three major championships have developed since the idea for Twenty20 was developed in Britain, two in India and one in the Caribbean funded by the billionaire Allen Stanford. However each of them has serious challenges to overcome. The Stanford Super Series 20/20 has fallen into disrepute after Stanford was arrested on charges of financial irregularities in his main companies, the Indian Premier League (IPL) has been relocated to South Africa in 2009 after only one season in India on security grounds and the Twenty20 Champions League has been postponed for a year after the Mumbai terrorism in 2008. For cricket, as with other sports, media relations are vitally important for its financial viability, but media coverage alone will not be enough to sustain the sport in uncertain times.

Mobile commodities:

4.1 A third feature of contemporary sport is the altering relationships between athletes, and the institutions and organizations that enable sport to operate. One way in which clubs and leagues can seek to maximise revenue, both during a crisis and as a means of expanding the audience for a sport, is to play more games. Another opportunity for sports is to create special or unusual events, such as the 150-metre sprint completed in record time by the Olympic 100 metre and 200 metre gold medallist Usain Bolt in May 2009 on a specially erected platform in central Manchester. Additional events, and fixtures played in different places than usual, are two ways forward for sports. Leading American sports, baseball, basketball, ice hockey and gridiron football, have pursued such an 'outsourcing' strategy for several years.4.2 Major League Baseball (MLB) began an All-Stars tournament against a Japanese selection drawn from the Nippon Professional Baseball league (NPB) in 1986 and has staged three regular season openings in Japan. The National Basketball Association (NBA) staged a pre-season match in London in October 2008 between Miami Heat and the New Jersey Nets, and has the overriding ambition of developing interest in the game in China. The National Hockey League (NHL) played games in London in 2007 (Anaheim Ducks v LA Kings) and two regular season games in Stockholm and Prague in 2008. The National Football League (NFL) has been developing a global strategy for the past three decades, but in 2007 and 2008 staged regular season games at Wembley Stadium in London for the first time. This meant that one of the eight home games for Miami Dolphins in 2007 (v New York Giants) and New Orleans Giants (v San Diego Chargers) in 2008 was played thousands of miles away. Such developments have led to suggestions that EPL teams might play a '39th game' somewhere in the world other than England, although this has not met with much support to date.[1]

Governing Bodies:

5.1 Government policies surrounding sport and lifestyles have demonstrated the importance of governing somatic developments in late modern society (Horne, 2006). Obesity has developed as a, if not the, major public health concern. Strategies for health and active living have begun to revolve around tackling obesity and increasing involvement and engagement in sport. Obesity rates are estimated to have doubled in England in the 14 years between 1993 and 2007. Hence targets have been set for reducing obesity and promoting healthy living; the 'Change4Life' strategy costing the government £75 million over 3 years was launched at the beginning of 2009. The government's sports event strategy includes the ambitious legacies projected for London 2012 for increasing participation in active sport. Driving up participation in sport and hosting major events have been recurring themes of the New Labour Governments since 1997. Other confirmed events include the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, also staged in Manchester in 2002, and forthcoming bids to host the Rugby Union World Cup (2015), the Football World Cup (2018) and the Cricket World Cup (2019).5.2 Despite concerns that the London 2012 Olympics might not have been bid for if the economic conditions at the end of the decade had existed at the beginning of it, the British Government Olympic Executive seek to reassure the public that the London 2012 Games will have a positive impact during an economic downturn in terms of creating opportunities for employment, business, and tourism. So whether in stable or economic crisis conditions hosting a sports mega-event is now perceived as a good thing for promoting government policies in the rhetoric of boosters. Exactly how these strategies will impact on individual people's engagement may revolve around a better appreciation of the perceived value active participation in sport and physical activity has for different sections of the population. This relates to the connection in consumer culture between lifestyle and personal identity, to which we now briefly turn.

The creativity and construction of physically active lifestyles:

6.1 Booklets to help readers "Get fit the Olympic way" were given away with a national newspaper at the start of 2009 and offered advice from British Olympic medallists on how to train. They joined the usual exhortations at that time of the year to create "A New Year. A New You" and "Burn Fat. Get Fit. Look Good". In the current economic climate promotional brochures for a health club proclaim: "Feeling the pinch? It's time to invest in yourself…". In this and other ways developing a physically active 'lifestyle' has become one of the most prominent features of consumer culture in the past three decades, confirming a prediction of the first social scientist to systematically review it as a concept (Sobel 1981). Understood broadly as "the distinctive pattern of personal and social behaviour characteristic of an individual or a group" (Veal 1993, p. 247) lifestyle contains within it meanings of both the possibilities of individual and collective creativity and the potential for imposed consumerist conformity and control. Which it offers is an empirical question that cannot be fully answered in this brief article, but in the past thirty years it has underpinned conceptual and theoretical challenges to the prevailing social scientific orthodoxies in the study of sport and leisure.6.2 Coakley (1993) for example summarised research into involvement in sport derived from this conceptual shift in three ways: that it involved a process of identity construction and confirmation; the establishment of personal identity was a primary factor in decision making over participating or not participating in sport; and individuals and groups create and negotiate their involvement in sport. This emphasis on active individuals making choices is symptomatic of the positive qualities attributed to lifestyle. Chaney (1996p. 86) concluded that as a concept lifestyle was able to capture "processes of self-actualization in which actors are reflexively concerned with how they should live in a context of global interdependence". It has been suggested that lifestyle sports, such as windsurfing, skateboarding and snow boarding, offer a challenge to high-performance, achievement orientated, sports. "In contrast to capitalism's temporal production, lifestyle sport time is immediate and discontinuous" (Wheaton 2007, p. 298). But are lifestyle sports subversive, resistant or merely just another way of playing under capitalism?

6.3 Many people engage in sport as a means of shaping up to the requirements of life in the 21st century. Sport is a preparation for living flexibly in a competitive capitalist world. It is also a great source of friendship/community involvement that enables people to escape (if only momentarily) from that world. For some participation and involvement in sport in contemporary capitalist consumer culture is a 'both/and' relationship – both engagement in sport mixed with awareness of exploitation. For others sport is too overblown and is avoided. There is a clear gender division about sport in this regard. Critics argue that the use of lifestyle images in popular culture and official strategies and policies to create depictions of particular ways of life not only differentiates and fragments social groups, it also acts as a political concept. For example by linking lifestyle to health on the basis of solving social problems by individualising them serves to deflect people's attention away from other "forms of collective, social action" (O'Brien 1995, p. 193). Lifestyle can be used in the construction of ways of life and create rather than resolve social problems.

6.4 Whilst there appears to be a greater degree of choice of leisure and sport than ever before, non-communicable diseases, such as obesity, have increased. Is there a relationship between these things? One answer is to say that people are not sufficiently concerned about obesity and their health. Another is that people are not sufficiently able to make healthy choices given wider sets of social relationships, institutions and processes. Hence, despite occasional healthy eating campaigns run by retail supermarkets, during popular sports events such as the Football World Cup many of the related deals offer 'snack foods', including beer, soft drinks, pizza, chocolate, biscuits and potato chips, in exchange for entering sport event related competitions. The largest sports mega-events accept sponsorship from makers of calorie-dense beverages and food, and equipment that fosters sedentary activities such as watching television and using motorised transport. In this way it could be said they actually promote mortality, morbidity and disability as they contribute to the global spread of obesity or 'globesity' (Dickson & Schofield 2005).

Conclusion

7.1 This brief article has indicated a few ways in which modern competitive sport and large-scale sport events have developed in line with the logic of (late) capitalist modernity. Sports consumer politics has not usually been at the centre of anti-capitalist debates and campaigns. It is possible that debates surrounding the staging of global mega events can make connections with wider issues – such as human rights, democratisation and social equality - but mostly sport has been a forum for at best reformist politics rather than cultural revolution. The sociological and social scientific study of sport, understood both as ritualised, rationalised, commercial spectacles and bodily practices that create opportunities for expressive performances, disruptions of the everyday world and affirmations of social status and belonging, faces the same concerns as other sociological domains of interest in the current economic conditions with its own specific public issues and private troubles.Notes

1 Whilst the increasing mobility of sports talent has been an issue for researchers in the past 20 years, a novel twist is that the family of Novak Djokovic, then world number 3 in ATP tennis rankings, bought the organising rights of the bankrupt Dutch Open (Amersfoort) in 2008. In May 2009 the first Serbian Open was played near Djokovic's hometown in Belgrade as a part of the ATP World Tour. Djokovic won the tournament.

References

CHANEY, D. (1996) Lifestyles London: Routledge.CLARKE, J. & Critcher, C. (1985) The Devil Makes Work: Leisure in Capitalist Britain Basingstoke: Macmillan.

COAKLEY, J. (1993) 'Sport and Socialisation' in J. O. Holloszey Ed. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, Volume 21 New York: Williams & Wilkins Publishing, pp. 169-200.

DICKSON, G. & Schofield, G. (2005) 'Globalisation and globesity: the impact of the 2008 Beijing Olympics on China' International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 1 (1/2) pp. 169-179. [doi:10.1504/IJSMM.2005.007128]

GIBSON, O. (2009a) 'Where will the big bucks go when the bubble bursts?' The Guardian Sport section, 22 January, pp. 6-7.

GIBSON, O. (2009b) 'Olympics are the jewel in the crown but cricket is the flashpoint' The Guardian Sport section, 23 January, pp. 6-7.

HATTENSTONE, S. (2009) 'Sir Fred, just say sorry', The Guardian, 24 January, pp. 28-29.

HORNE, J. (2006) Sport in Consumer Culture Basingstoke: Palgrave.

MARX, K. & Engels, F. (1969[1848]) Manifesto of the Communist Party, Moscow: Progress Publishers.

O'BRIEN, M. (1995) 'Health and Lifestyle: a critical mess?' in R. Bunton, S. Nettleton & R. Burrows Eds. The Sociology of Health Promotion, London: Routledge, pp. 189-202.

SELVEY, M. (2008) 'This mercenary match will resolve none of England's dilemmas' The Guardian 'Sport' section 27 October, p. 10.

SOBEL, M. (1981) Lifestyle and Social Structure Academic Press.

TAYLOR, I. (1989) 'Hillsborough, 15 April 1989: Some Personal Contemplations' New Left Review 177, pp. 89-110.

VEAL, T. (1993) 'The concept of lifestyle: a review' Leisure Studies 12 pp. 233-252. [doi:10.1080/02614369300390231]

WHEATON, B. (2007) 'After Sport Culture: Rethinking Sport and Post-Subcultural Theory' Journal of Sport and Social Issues 31(3) pp. 282-307. [doi:10.1177/0193723507301049]