The Meanings of Sleep: Stories from Older Women in Care

by Brooke Davis, Bernadette Moore and Dorothy Bruck

Victoria University

Sociological Research Online 12(5)7

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/7.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1620

Received: 8 Jan 2007 Accepted: 29 Aug 2007 Published: 30 Sep 2007

Abstract

This paper analyses data from a two phase project which utilizes a mixed methods design to investigate the construct of 'good' and 'poor' sleep quality amongst older women in Australian residential care. Phase one of the study demonstrates the lack of congruence between quantitative measures of sleep behaviour and self categorizations by the participants as 'good' or 'poor' sleepers. This lack of congruence is explored in the second phase of the project where semi structured interviews investigate the process by which self categorizations emerge. Interview data ratifies the findings of phase one identifying that the process of self-categorization is not necessarily linked to sleep behaviours, as many of these phenomena such as nocturnal disruption, or early morning awakenings were similarly described by self-categorized 'good' and 'poor' sleepers. Rather, it appears that these women, through the process of upward and downward social comparison, construct ideas about 'normal' sleep, and it is this normative definition, rather than the sleep phenomena experienced, that the individual uses to provide a benchmark for their self-categorization of sleep quality.

Keywords: Women, Aged-Care, Subjective Sleep Quality, Self-Categorization, Social Comparison, Temporal Comparison

Introduction

1.1Almost half of all older people will experience sleep disruption (Vitiello, Larsen, & Moe, 2004) and many will attempt to manage this with the use of hypnotic medications (Endeshaw, 2001). Despite the subjective experience of poor sleep quality often acting as the driver for help seeking and subsequent hypnotic use, there is limited understanding of (i) the relationship between these subjective experiences and objective determinants of sleep quality and (ii) the processes by which an individual attributes meaning to their personal sleep experiences and subsequently understands themselves to be a 'good' or 'poor' sleeper. This paper reports on a two part mixed methods study that addresses this process of self-categorization amongst a group of older women who were all residents in an aged care home in Australia. In Phase One of the study quantitative data from 46 participants documented the women's sleep behaviours and this data was compared to inductive self-categorizations of 'good' or 'poor' sleep quality provided by the participants. Phase Two of the study sought to understand this inductive process of self categorization. A subset of 18 women participated in semi-structured interviews where they were able to describe their sleep phenomena, the meanings they attributed to these phenomena, and their subsequent processes of self-categorization.1.2In 1957, Dement and Kleitman changed our understanding of sleep from being a mystical, death-like state to a complex system of predictable and cyclical electrical discharges that could be displayed and recorded. This capacity for a real time display of sleep, meant that ownership of this once private space was relocated to a public, scientific domain. Scientific communities evolved around the electrophysiological definition and measurement of sleep (Chervin, 2005). Sleep was now quantitatively observable, measurable and hence subject to evaluation against socially constructed normative data. The search to then define the boundaries of 'normal' sleep resulted in the development of a range of indices to measure nocturnal sleep and daytime sleepiness.

1.3 There are at least three methodological approaches to evaluating sleep quality. One methodological group consists of the objective, quantitative methods such as the electrophysiological data, commonly used to generate indices such as sleep latency (time to fall asleep), sleep efficiency (total time asleep relative to total time spent in bed) and sleep fragmentation (total time of wakefulness during the night following initial sleep onset) (Dement, Miles & Carskadon, 1982) which, when compared to normative values, allow for the classification of sleep as 'normal' or 'abnormal', 'non pathological' or 'pathological', 'good' or 'poor'. Outside of the sleep clinic, actigraphy, which infers sleep episodes from recordings of wrist movement (passivity, implying sleep, and or activity, implying being awake), has also established credibility as an objective means of establishing sleep parameters and therefore sleep quality. A second group of sleep measures are the subjective, quantitative evaluations which are based on self report questionnaire data, for example the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al. 1989), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (Johns, 1991) or the Karolinska Sleep Diary (Åkerstedt et al., 1994), which all provide self ratings of sleep behaviours and / or subjective sleepiness. A third method, about which there is comparatively little published data, is the subjective, qualitative approach which asks people to report their experiences of sleep and the meanings and interpretations they make about their own sleep quality.

1.4 An overview of the literature pertaining to the measurement of sleep quality identifies two key themes. Firstly, the more objective and quantitative the measuring tool the greater the assumed 'truth' about sleep quality: Electrophysiological measures of sleep are often described as the gold standard of measurement (Chervin, 2005). From this gold standard, sleep scientists propose a hierarchy with decreasing credibility as measurement moves from objective data to subjective self-reporting. Secondly, significant discrepancies have been found between objective and subjective measuring instruments (Vanable et al., 2000; Vitiello et al., 2004; McCrae et al., 2005) and this lack of concordance is, in part, attributed to the assumption that subjective (self-report) measures are of limited credibility and that individuals are poor judges of their own sleep experiences. Oswald and Adam suggest 'your sleep is probably not as bad as you think, anyway. We really are all very inaccurate in our judgements …' (1983, p.72). These dual themes within the scientific literature clearly argue that accurate knowledge about sleep quality is predominately located outside the experience of the individual and this perhaps explains the current neglect within the professional sleep literature to explore the experience of sleep from a qualitative perspective.

1.5 One study which utilised a qualitative phenomenological approach to investigate the process by which individuals determine how well they slept found that self-perceptions of 'good' and 'bad' sleep were influenced by a series of 61 environmental, cognitive, time passage, and physical factors (Kaufman, 2001). The same author also noted that while some common factors were represented in most individual's understanding of sleep quality, the high degree of individual variation indicated that people define good and poor sleep in ways that are more individualized than current measures allow for (Kaufman, 2001). Similarly Hislop and Arber (2003) in their descriptions of women's sleep experiences argue that the research literature often fails to acknowledge the social context within which a woman's sleep occurs and that understandings of sleep are enhanced by attention to the stories women tell and the meanings they attribute to their experiences. For example, Hislop and Arber (2003) note, that although the majority of women in their study, had, at some point in their lives, experienced either chronic or acute sleep problems, only one woman named her experience of sleep disruption using the term 'insomnia'. Hislop and Arber suggest this occurs because the 'women perceive sleep disruption as a normal 'fact of life' outside the scope of medicalization' (Hislop and Arber, 2003, p.822).

1.6 From the perspective of the individual, 'poor' sleep is clearly a significant concern with research suggesting that this concern increases with increasing age (Buysse et al., 1991). A diverse range of physiological, medical and psychosocial factors have been linked to the potential for a high prevalence of reported insomnia in older populations (Ancoli-Israel, 1997). Psychophysiological studies have demonstrated the clear impact of this range of risk factors on objective sleep quality for older persons whose sleep is characterised by increased time falling asleep (sleep latency), decreased total sleep time and lower sleep efficiency (Dement et al., 1982). Such findings of increased objective sleep impairment with ageing are certainly supported by the subjective experience of poor sleep quality reported by up to 50% of persons aged over 65 (Ancoli-Israel, 1997) but, interestingly, even healthy adults who do not complain about their sleep are evaluated objectively as having poorer sleep quality than their younger counterparts (Vitiello et al., 2004).

1.7The relationship between measures of objective sleep quality and subjective sleep quality in ageing is complex. McCrae et al. (2005) suggest that the congruence between these measures of sleep quality identifies four categories of sleepers – i.e. good sleepers, complaining poor sleepers, non-complaining poor sleepers and complaining good sleepers. Several studies have attempted to understand the factors that discriminate between these groups. For example in a study involving 150 non-complaining older sleepers, Vitiello et al. (2004) found that despite their lack of perception of poor sleep quality, significant proportions of the sample demonstrated objective sleep disruption. Older men had objectively poorer sleep quality than women, although women were more likely to report subjective experiences of poor sleep. Congruence between subjective and objective measures of sleep quality was found to be stronger in males than females. Vitiello et al. (2004) suggest that these findings of disjunction between objective and subjective sleep measures may indicate that older persons adjust their expectations of sleep by establishing new, as yet undefined, evaluative criteria against which they self categorise as 'good' or 'poor' sleepers. Vitiello et al. (2004) further suggest that differential criteria may be established for men and women and '…what we consider objective measures of good sleep may be appropriate for older men but that older women may be evaluating their sleep quality using other criteria' (p. 504).

Aims

2.1 This paper describes a component of a larger research study that seeks to further understand this complex concept of 'good' and 'poor' sleep quality in ageing. Aligned with the position of Denzin (1978) who argues that 'each method reveals different aspects of empirical reality' (p28) a mixed methods approach is employed. Phase one of the study replicates the dominant hypothetico-deductive model of sleep research where validated instruments provide quantitative data for the categorization of sleep quality. This quantitative data is triangulated with a phenomenological-inductive approach of self categorizations that are generated by the participants. A second phase of the study then seeks to explore this inductive self categorization by the participants as 'good' or 'poor' sleepers to understand the process by which these older women locate themselves within these categorizations.2.2 The study chose to focus on the experiences of older women and more specifically older women living in low dependency care facilities in Australia. The rationale for focusing on older women emerged from several lines of research, which highlight the potential for the categorization of sleep quality to significantly impact on the lives of older women, particularly those in residential care. For example (i) elderly women are more likely to complain of poor sleep than their male counterparts, despite the objectively poorer sleep of men (Vitiello et al., 2004); (ii) perceptions of decreasing sleep quality are both a risk factor for women to require institutionalisation and an outcome subsequent to admission (Pollack and Perlick, 1991); and (iii) research demonstrates that 69% of women in low-dependency residential aged care are regularly prescribed hypno-sedative medication and this occurs despite the apparent lack of correlation between the use of this medication and subjective sleep quality (Monane et al., 1996). These findings, along with Vitiello et al.'s (2004) assertion that older women may evaluate their sleep by unknown criteria, provide a sound rationale for investigating perceptions of sleep quality among this study group.

Methods

3.1 Forty six Australian older women living in low-care residential facilities participated in the study. In Australia this collective-setting accommodation is typically structured as a private bed-sitting room in a private or public facility that provides 24-hour nursing and other support. The level of care provided varies considerably between facilities, but residents are typically female, independently mobile and able to manage basic personal care. Meals are usually supplied, though some residents may have basic kitchen facilities available.3.2 Initial recruitment of study participants involved approaching residents individually. However, ethical concerns were raised when that recruitment process was observed to elicit participation that reflected both an eagerness to comply with researchers' requests, and a desire for social engagement. As the aged-care population to which the study group belonged was considered vulnerable, this practice ceased and all subsequent recruitment was through residents' meetings, where residents approached staff after the meeting to register their interest. Volunteers were considered suitable for participation provided that staff could identify them as not suffering dementia or other cognitive impairment, serious psychiatric illness, or uncontrolled, acute physical illness. The women who participated were typically widowed, were currently satisfied with their overall health, and walked either unaided or with a walking frame. They were considered by facility staff, to be models of 'healthy aging' within a residential care context. The ages of the group ranged between 61 years and 98 years with a mean of 85.8 years (SD= 7.9). Participants were asked to make Sleep Quality Related Self Categorisations (SQRSC) as 'good' or 'poor' sleepers (n= 22 and 24 respectively), and equivalent group sizes were sampled to enable comparison between groups. No specific rating criteria were provided for participants and the self-categorisations were therefore seen to represent intuitive evaluations by participants. Self-categorised 'good' sleepers were excluded from the study if they were taking benzodiazepines.

3.3 All women completed the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI: Buysse et al., 1989), and a range of psychosocial measures, including measures of depression, anxiety, quality of life, and sleep beliefs. (Only the PSQI data will be reported in this study). The PSQI is a 19-item self-report questionnaire that assesses sleep quality and sleep disturbance over the previous month. The items generate a global PSQI score (range 0-21), which is the sum of the seven component scores (range 0-3), as follows: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency (time to fall asleep), sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction.

3.4For the second phase of the study, a sub-sample of 18 women was selected on the basis of their SQRSC and willingness to engage in a 90 minute interview. These 18 women participated in individual in-depth interviews (45-90 minutes) in their own rooms. All interviews were tape recorded and later transcribed. This second phase comprised ten 'good' and eight 'poor' sleepers, of the 'poor' sleepers four reported long-term benzodiazepine usage for at least six months prior to the study.

3.5Using a semi-structured interview format women were asked to describe their experiences across three broad areas: (i) Their experiences of good and poor sleep; (ii) Their non medicalised strategies for improving sleep, and,, (iii) Their use of sleeping medications. The first theme encouraged women to describe times they slept well and times they slept poorly, including the sleep phenomena they experienced and the context in which they occurred. Under the domain of improving sleep, women were asked to give examples of sleep problems they had experienced and the steps they had taken to improve their sleep. Finally, women utilizing benzodiazepines were asked about the process of initial prescription, their history of usage, withdrawal attempts and their perceptions of the impact of the medications on their sleep quality. All aspects of this study were approved by the Victoria University Ethics Committee.

3.6The recorded interviews were analysed in accordance with the empirical phenomenological approach (Giorgi, 1997). Participant stories were broken into meaning units that were labeled according to the themes they reflected. The meaning units were then synthesised according to their labels, such that the essential meaning of the woman's story was conveyed. To validate the data analysis descriptions were initially returned to participants. This was found to be unsatisfactory, however, when participants were unable to critically review the document and demonstrated an overriding desire to be supportive of the researcher's analysis. To ensure credibility therefore of the derived meanings and overcome potential biases in the data analysis a second researcher independently analysed samples of the data. This process of 'triangulating analysts' being described by Patton (1990) as an appropriate method of data validation.

Results Phase 1: Comparison of Quantitative Data with Self Categorizations of Sleep Quality.

Relationship between PSQI data and Self-Categorisations of Sleep Quality.

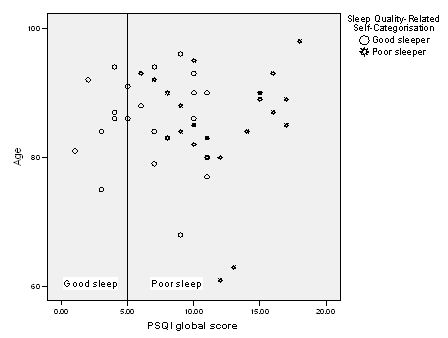

4.1 All study participants completed the PSQI, which is a widely used scientific measure of sleep quality. This data was then plotted against the Sleep Quality Related Self-Categorisation (SQRSC), see Figure 1.| Figure 1.PSQI global score of self-categorised ‘good’ and ‘poor’ sleepers by age of woman (n=46). |

|

4.2 Visually, Figure 1 suggests several trends. A substantial range of global PSQI scores is evident. Using the PSQI, the conventional cut-off point for clinically defined sleep disturbance is a score of 5. However, only a fifth of these older women (9/46) did not have sleep problems according to the PSQI criterion. Whilst all SQRSC 'poor' sleepers fell within the PSQI poor sleep range, over half of the SQRSC 'good' sleepers scored higher than the cut-off score, classifying them as having poor sleep quality on the basis of the PSQI global score. To understand these trends more clearly, mean PSQI global scores were calculated and differences examined between SQRSC good and poor sleepers. Table 1 below provides these summary statistics.

|

4.3 Table 1 demonstrates that these older women as a whole were rated as poor sleepers using the benchmark PSQI global score of 5 as the discriminator of good and poor sleep. Even SQRSC 'good' sleepers demonstrated a mean score of 6.4 placing them within the PSQI poor sleep range. The mean PSQI score for SQRSC 'poor' sleepers of 11.9 was significantly greater than that of good sleepers (p<.001). Our findings therefore replicate those already reported in the literature. Self categorized poor sleepers appear to demonstrate poorer sleep quality than self categorized good sleepers (McRae et al., 2003; Vitiello, et al., 2004). However significant proportions of older, self categorized, good sleepers, are still demonstrated to have PSQI scores indicative of sleep disturbance (Vitiello et al., 2002; Vitiello et al., 2004). Such findings have been interpreted as evidence that decreased sleep quality associated with ageing does not necessarily lead to perceptions of diminished sleep quality, as older individuals may alter their benchmark criteria for self categorization of sleep quality (Buysse, et al., 1991; Vitiello et al., 2004). It is this process of establishing a benchmark for categorization that is the major area of investigation in the second phase of this study.

Phase 2 Understanding the Process of Self Categorization of Sleep Quality

Describing sleep phenomena

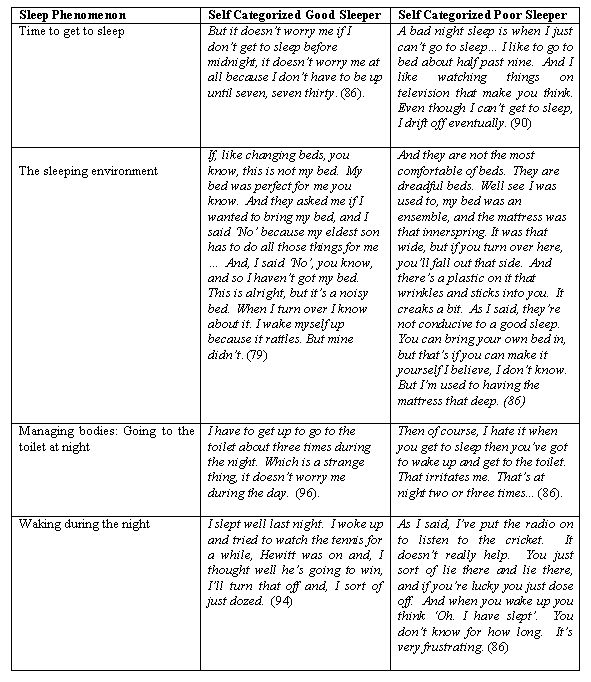

5.1 Analysis of the interview transcripts from the 18 women involved in stage two of the study showed that both 'good' and 'poor' sleepers related experiences of their sleep in terms of the four categories of sleep onset, waking during the night, early morning awakening, and daytime sleepiness. Within the category of 'waking during the night', both 'good' and 'poor' sleepers identified a range of factors that disturbed their sleep. Predominately they spoke of the impact of aspects of their sleep environment, needing to go to the toilet at night and worry. Participants also described strategies for managing periods of wakefulness during the night. Quotes representative of participants' experiences of some of these phenomena are given in Table 2 – for each phenomenon described, a representative quotation from both a self categorized 'good' (GS) and 'poor' sleeper (PS) is provided. Ages of respondents are included in brackets after each quotation.| Table 2. Representative descriptions of sleep phenomena by self categorized good and poor sleeping women |

|

5.2 The excerpts of women in their dialogues about sleep shown in Table 2, provide an interesting insight into their nighttime sleep experiences. The first theme that is evident from these dialogues is that irrespective of their self-categorization as a 'good' or 'poor' sleeper the women were reporting significant disruptions in both getting to sleep and staying asleep during the night. For both good and poor sleepers their sleep was characterized by difficulties falling asleep and disruptions to sleep continuity as a consequence of factors such as the discomfort of their sleeping environment and needing to go to the toilet several times each night. Both categories of women also reported experiences of early morning awakening.

5.3 These findings are congruent with previous work that identifies that even non-complaining elderly sleepers will experience significant sleep disruption (Vitiello et al., 2004). The PSQI has categorized most women in this study as experiencing sleep disturbance and their stories ratify this quantitative assessment. A reading of the interview transcripts also highlights that not only do both categories of women experience similar types of sleep disturbance but that many of the phenomena experienced are similar for both ‘good’ and ‘poor’ self categorized sleepers. For example for many women the nighttime was a time when they continually engaged in activity directed at managing their bodies. One of the most commonly reported body-related sleep complaints was frequently needing to go to the toilet. Both the examples provided from good and poor sleepers report an identical frequency of going to the toilet during the night and on this criterion the self-categorizations could not be distinguished.

5.4 It is however in the women’s interpretations of these events that possible differences between the self categorizations emerge. The ‘good’ sleeper reflects on this disruption as a ‘strange’ thing, whereas the ‘poor’ sleeper ‘hates’ this ‘irritating’ disruption. Such divergent responses to similar events require further study. They may partly be explained by the tenants of cognitive psychotherapy (Ellis, 1962). First described by Epictetus (cited in Corey, 2001) this philosophy argues that ‘People are disturbed not by things, but by the views they take of them’ (p.298) or as explained fifteen centuries later by Hamlet ‘…. there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so’. What then is the thinking, the meaning women attach to these objectively similar sleep phenomena, that leads to the subjective interpretation of their sleep experience as good or bad?

The meanings of sleep phenomena.

5.5 In exploring the meanings that older women attach to the sleep phenomena they experience it was evident that most self-categorized ‘poor’ sleepers (PS) had similarly high, and perhaps unrealistic, expectations about their sleep. When asked how they imagined a good night’s sleep would unfold, they responded consistently that good sleep would be to sleep through the night without waking:

"Well for me a good night's sleep is, if I put the TV on at half past ten and if can go to sleep by eleven o'clock and sleep through, till six in the morning". (PS, 80)"A good night would be to go to bed at ten or thereabouts, and just sleep until the morning. That's it". (PS, 92)

"A good night would be if I could sleep all night. That would be a miracle. Also, you need to feel well all the time, to have a good sleep". (PS, 88)

"A good night would be to sleep through. The waking up is the only thing that worries me. There's nothing else". (PS, 94)

"I think the time I go to bed is reasonable, for my age, and tiredness. Um, perhaps get up once would be normal, and perhaps sleep until seven in the morning. That would be an ideal pattern". (PS, 90)

5.6 Understanding the processes by which these older women established their perceptions of ‘normal sleep’ is perhaps the key to understanding why some older women in aged-care make different self-categorizations despite reporting similar experiences of sleep phenomena. One framework for understanding this process of categorization is social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954). In developing this theory Festinger argued, that, in the absence of objective criteria, individuals are able to make sense of their world by comparing their experience to others. The process of downward social comparison, where individuals seek comparison with others worse off than themselves, is proposed to increase personal satisfaction, whereas upward social comparison may leave the individual feeling more dissatisfied with their experiences. For older people downward social comparison is seen to offer some protection against the loss of control that accompanies ageing (Heckhausen and Brim, 1997; Frieswijk et al., 2004).

5.7 The stories of women in the current study often incorporated reference to social comparison of their sleep phenomena. As would be predicted ‘good’ sleepers (GS) tended to engage in either (i) downward social comparison, where they compared their own sleep quality to that of a perceived worse-sleeping reference group, or (ii) lateral social comparison where women made a comparison between their own sleep and that of a reference group with perceived similar sleeping patterns. As such, self-categorised ‘good’sleepers subsequently appraised their sleep to be normal or better than normal:

"I do have a lot of sleep. Much more than a lot of the other girls around there." (GS, 94)"I think I'm a good sleeper, you know. When you hear all the others, they all say the same things. They don't get to sleep very early." (GS, 88).

"I have to get up to go to the toilet about three times during the night…like a lot of them (other residents) say, that wakes you up you see, and then it sometimes takes a while to get on." (GS, 96)

5.8 In contrast, 'poor' sleepers did not tend to engage in downward or lateral social comparison when discussing their sleep quality. Conversely, some appraised their sleep as worse than normal on the basis of upward social comparisons, or comparison with a better-sleeping reference group:

"I don't sleep during the day either, because I just can't sleep. I've got a friend who can go off like that for ten minutes. But I can't. I'm supposed to lie down every day for an hour, but I never go to sleep." (PS, 90)"I can't (nap during the day). Just can't do it. You see the others, they say they have a sleep in front of the telly, but I can't. Sometimes it would help the afternoon to pass, but I just don't go to sleep." (PS, 87)

5.9 For some women, a lack of social interaction, or just the lack of exposure to others' stories of sleep, may result in them being unable to access social comparisons by which to establish their own self categorizations.

"I go to breakfast and have a conversation with some of the ladies at the table, but then they all choof off, and no one is interested…I don't even know where their rooms are. I only see them at the dinner table and that's it". (PS, 81)

5.10 These women, who seem to lack access to social comparison groups, often reverted to temporal comparison strategies to make meaning of their sleep experiences. These temporal comparisons were usually upward in direction i.e. they compared their current sleep quality to the better-quality sleep they recalled from an earlier time in their lives (Albert, 1977): "But one time I used to put my head down and sleep right through. A few years ago, my mother used to tell me 'I could sleep on a barbed wire fence'. Oh, I was a good sleeper, love. But as you get older, I think it changes, your sleep pattern changes a bit. But since I've been here, it has changed an awful lot". (PS, 86)

"My sleep pattern has changed terribly since I was younger. I never had problems like this. I slept pretty well…No this strange unusual pattern has developed, I suppose, over the last five or six years, perhaps even less… No, it's quite different to what it was when I was younger. I never had sleep problems". (PS, 90)

5.11 It appeared therefore, that a key difference between self-categorised 'good' and 'poor' sleepers was not in their actual experience of sleep phenomena, but rather in the way that they thought about their own sleep quality, in the wider context of their construction of normal sleep, which was often based on their engagement with comparison strategies. Downward social comparison was most commonly employed by self-categorised 'good' sleepers. Self-categorized 'poor' sleepers on the other hand, tended towards upward social comparisons, but where they had limited access to social comparison groups, they tended to engage in temporal comparison to an earlier period of their lives.

Conclusions

6.1 This paper has[H1] identified the lack of congruence between quantitative and qualitative measures of sleep quality. Numerical determinants of sleep quality derived through structured measures such as the PSQI fail to align with the qualitative descriptions of equivalent sleep phenomena, obtained through semi structured exploration. Interestingly, the ‘hard data’ of sleep medicine, phenomena such as sleep onset latency and nocturnal awakenings are both derived by quantitative methods and described by qualitative methods. Yet these measures, which, within the domain of sleep medicine are definitive of sleep quality, are seen within this study, to not be sufficient to describe the experience of sleep quality among older women. The stories the women told were founded on these behaviours yet it was only in their interpretations that their experience of sleep quality was derived. The bounds of the stories presented here are shaped not only by the women who shared them, but as in all qualitative research, by the interests and knowledge of the researchers, and by constraints of the organisations involved. As such, whilst this study identified the use of social and temporal comparison as a means by which the women interpreted their experiences there are potentially many alternate layers of meaning that may be located outside of the current work and found within their personal biographies of sleep. It remains for future research to record and understand these biographies and their relationship to the attribution of meaning.

6.2 The stories told in this study may not resonate with those of older men or even of women of different ages, living in different social contexts, of different health status, or cultural backgrounds, but they do tell their own stories, and, in doing so, highlight the importance of balancing the increased drive for the medicalization of sleep with an understanding of the personal and social context within which this sleep occurs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank BaptCare, Victoria, Australia and Victoria University for their ongoing support of this project.

References

ÅKERSTEDT , T., HUME, K. and MINORS, D. (1994) 'The Subjective Meaning of Good sleep. An Intraindividual Approach using the Karolinska Sleep Diary', Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 79, pp. 287-96.

ALBERT, S. (1977) 'Temporal comparison theory', Psychological Review, Vol. 84, pp.485-503.

ANCOLI-ISRAEL, S. (1997) 'Sleep Problems in Older Adults: Putting Myths to Bed', Geriatrics, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 20-28.

BUYSSE, D., REYNOLDS, C. F., MONK, T., BERMAN, S. R., AND KUPFER, D. J. (1989) 'The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research', Psychiatric Research, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 193-213.

BUYSSE, D.J., REYNOLDS, C.F., MONK, T.H., HOCH, C.C., YEAGER, A.L. and KUPFER, D.J. (1991) 'Quantification of Subjective Sleep Quality in Healthy Elderly men and Women Using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)', Sleep, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp.331-338.

CHERVIN, R.D. (2005) 'Use of Clinical Tools and Tests in Sleep Medicine' in M.H. Kryger, T.Roth and W.C. Dement (editors) Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier / Saunders.

COREY, G. (2001). Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy (6th ed.). Sydney: Wadsworth. p. 298.

DEMENT, W. and KLEITMAN, N. (1957) 'Cyclic Variations in EEG During Sleep and their Relation to Eye Movements, Body Motility, and Dreaming', Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, Vol. 9, pp.673-690.

DEMENT, W., MILES, L.E. and CARSKADON, M.A. (1982) 'White Paper on Sleep and Aging', American Geriatric Society, Vol. 30, pp.25-50.

DENZIN, N.K. (1978). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

ELLIS, A. (1962) Reason and Emotion In Psychotherapy. Secaucus, NJ : Citadel.

ENDESHAW, Y. (2001) 'The role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of insomnia' Geriatric Literature, Vol. 49, pp. 824-826.

FESTINGER, L. (1954) 'A theory of social comparison processes', Human Relations, Vol. 7, pp. 11-16.

FRIESWIJK, N., BUUNK, B. P., STEERINK, N. and SLAETS, J. P. J. (2004) 'The effect of social comparison information on the life satisfaction of frail older persons', Psychology and Aging, Vol. 19, No.1, pp.183-190.

GIORGI, A. (1997) 'The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure', Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, Vol. 28, No.2, pp. 235-260.

HECKHAUSEN, J. and BRIM, O. G. (1997) ' Perceived problems for self and others: Self-protection by social downgrading throughout adulthood', Psychology and Aging, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 610-619.

HISLOP, J. and ARBER, S. (2003) 'Understanding Women's Sleep Management: Beyond Medicalization-Healthization? Sociology of Health & Illness, Vol. 25, No, 7, pp.815-837.

JOHNS, M.W. (1991) 'A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale', Sleep, Vol. 14, pp. 540-545.

KAUFMAN, D. (2001) 'The Subjective Experience of Sleep: Identification of the Hierarchical Structure of Subjective Sleep Quality', Dissertation Abstracts International:Section B: The Sciences & Engineering, Vol. 61(10-B), 5621.

KILLEN, J.D., GEORGE, J., MARCHINI, E., SILVERMAN, S., and THORESEN, C. (1982) 'Estimating sleep parameters: A multitrait-multimethod analysis', Jouranl of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 345-352.

MCCRAE, C.S., WILSON, N.M., LICHSTEIN, K.L., DURRENCE, H.H., TAYLOR, D.J., BUSH, A.J. and RIEDEL, B.W. (2003) ''Young old' and 'old old' poor sleepers with and without insomnia complaints', Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp.11-9.

MCCRAE, C.S., ROWE, M.A., TIERNEY, C.G., DAUTOVICH, N.D., DeFINIS,A.L. and McNAMARA, P.H. (2005) 'Sleep Complaints, Subjective and Objective Sleep Patterns, Health, Psychological Adjustment, and Daytime Functioning in Community-Dwelling Older Adults' , The Journal of Gerontology, Vol. 60, pp. 182-189.

MONANE, M., GLYNN, R. J. and AVORN, J. (1996) 'The impact of sedative-hypnotic use on sleep symptoms in elderly nursing home residents', Clin Pharmacol Ther, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 83-92.

OSWALD, I. and ADAM, K. (1983) Get a Better Night's Sleep. Singapore: Koon Way Printing.

PATTON, M.Q. (1990) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. (2nd ed). California:Sage:

POLLACK, C. P. and PERLICK, D (1991) 'Sleep problems and institutionalisation of the elderly', Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, Vol. 4, No.4, pp. 204-210.

VANABLE, P.A., AIKENS,J.E., TADIMETI,L., CARUANA-MONTALDO, B. and Mendelson, W.B. (2000) 'Sleep Latency and Duration Estimates among Sleep Disorder Patients: Variability as a Function of Sleep Disorder Diagnosis, Sleep History, and Psychological Characteristics', Sleep, Vol. 23, No. 1. pp. 71-79.

VITIELLO, M.V., LARSEN, L.H., DROLET, G., MADAR, E.L, and MOE, K.E. (2002) 'Gender Differences in Subjective-Objective Sleep Relationships in Non-Complaining Healthy Older Adults', Sleep, Vol. 25, Abstract Supplement 083.H, p. A61.

VITIELLO, M.V., LARSEN, L.H. and MOE K.E. (2004) 'Age –related Sleep Change Gender and Estrogen Effects on the Subjective-Objective Sleep Quality Relationship of Healthy, Noncomplaining Older men and Women', Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 56, No. 5, pp. 503-510.