Gender Roles and Women's Sleep in Mid and Later Life: a Quantitative Approach

by Sara Arber, Jenny Hislop, Marcos Bote and Robert Meadows

University of Surrey; Keele University; University of Surrey

Sociological Research Online 12(5)3

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/3.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1609

Received: 15 Jan 2007 Accepted: 15 Aug 2007 Published: 30 Sep 2007

Abstract

Women in mid and later life report particularly poor quality sleep. This article suggests a sociologically-informed quantitative approach to teasing out the impact of women's roles and relationships on their sleep, while also taking into account women's socio-economic characteristics and health status. This was accomplished through analysis of the UK Women's Sleep Survey 2003, based on self-completion questionnaires from a national sample of 1445 women aged over 40.

The article assesses the ways in which three central aspects of women's gender roles: the night-time behaviours of their partners, night-time behaviours of their children, and night-time worries – impact on women's sleep, while also considering how disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances and poor health may compromise women's sleep. Using bivariate analysis followed by hierarchical multiple regression models, we examine the relative importance of different aspects of women's gender roles. The key factors implicated in the poor sleep quality of midlife and older women are their partner's snoring, night-time worries and concerns, poor health status (especially experiencing pain at night), disadvantaged socio-economic status (especially having lower educational qualifications) and for women with children, their children coming home late at night.

Keywords: Sleep, Women, Gender Roles, Partners, Children, Socio-Economic Circumstances, Survey

Introduction

1.1 Articles in this Special Issue provide a sociological lens on gender and sleep across the life course, primarily based on qualitative research. The insights from qualitative research are an essential bedrock to frame sociological understandings in this novel area of enquiry. However, it is also important to consider how quantitative data can help unravel the understandings of sleep, particularly the extent to which sleep problems are embedded within broader gender and social inequalities within contemporary society.1.2 Yet researchers wishing to conduct quantitative studies on sleep are hampered by the lack of social surveys that collect data on sleep. Apart from Groeger et al.'s (2004) national survey of sleep, one of the few UK sources of nationally representative data containing questions on sleep is the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Psychiatric Morbidity Survey which interviewed over 8000 men and women in 2000 (Singleton et al., 2001). Data on sleep were collected in this survey because of the underlying assumption that poor quality sleep provides a marker of mental health problems, rather than because the survey designers had any interest in exploring the social contours of poor sleep quality. Sleep problems should not be seen as purely symptomatic of psychological ill-health, but are also intimately connected to wider aspects of the social context of everyday lives, and especially to gender roles and relationships.

1.3 This article goes beyond existing research by suggesting a sociologically-informed quantitative approach to teasing out the impact of women's roles and relationships on their sleep, while also taking into account women's socio-economic characteristics and health status. It accomplishes this through analysis of the UK Women's Sleep Survey 2003, which collected self-completion questionnaire s from a national sample of 1445 women aged over 40.

1.4 Following an overview of existing quantitative and qualitative research on women's sleep, and a discussion of methods, the article explores the impact of partners, children, worries, socio-economic circumstances and health on women's sleep through bivariate and multivariate analyses of women's quality of sleep.

AN OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON WOMEN'S SLEEP

Quantitative research on women's sleep

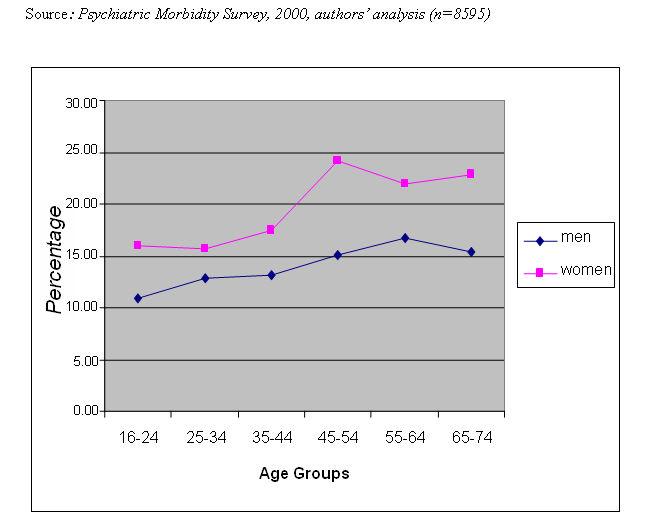

2.1 It is well-known in sleep research that women report higher levels of sleep complaints than men (Landis and Lent, 2006; Zhang and Wing, 2006; Groeger et al., 2004; Sekine et al., 2006). Groeger et al.'s (2004) UK survey of men and women aged 16-93 (n=1997) found that women reported more sleep problems than men at all ages, although sex differences below age 25 were small. The meta-analysis of 29 published studies on sex-differences in insomnia by Zhang and Wing (2006) concluded that the overall risk ratio of insomnia was 1.41 for women compared to men. This sex difference is broadly confirmed in our analysis of national data from the Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (unpublished) shown in Figure 1.| Figure 1. % of men and women reporting sleep problems 4 or more nights per week by age group |

|

2.2 Overall 20.5% of women and 15% of men report problems at least 4 nights per week with trying to get to sleep or with getting back to sleep, if they woke up or were woken up. Figure 1 shows that the group with the poorest reported quality of sleep are midlife women (aged 45-54) among whom almost a quarter report problematic sleep at least 4 nights a week. Women above this age (age 55-74) are almost as likely to report poor quality sleep. Similarly, Groeger et al. (2004) found that women aged 50-59 were the group most likely to report difficulty staying asleep and difficulty getting to sleep (31% and 20% respectively on 4 or more nights a week).

2.3 Various theories have been put forward by sleep scientists to explain the sex difference in reported sleep problems. The dominant explanation is one of biological or physiological sex differences, purported to relate to innate physiological differences between men and women (Manber, 1999), or women's hormone levels, particularly oestrogen. The assumption is that women's disturbed sleep is linked to their menstrual cycle, and adversely affected during pregnancy and the menopause because of changes in hormonal levels (Dzaja et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006).

2.4 Psychological explanations for women's poorer sleep are also prevalent (Lindberg et al., 1997). It is incontrovertible that individuals suffering from psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety, have poorer quality sleep (Piccinelli and Wilkinson, 2000; Ustun, 2000). However, research evidence shows that sex differences in quality of sleep remain after removing the effects of women's higher rates of psychiatric morbidity, and therefore cannot be explained solely by the higher levels of depression and anxiety among women (Lindberg et al., 1997; Zhang and Wing, 2006). In addition, evidence from longitudinal studies suggests that sleep problems often predate the onset of depression (Breslau et al., 1996). Therefore, prior sleep problems may play a causative role in the development of depression, rather than sleep problems being a sequelae of depression.

2.5 Scientific studies of sex differences in sleep much less often consider sociological explanations. While Groeger et al. (2004) found that women reported more sleep difficulties than men, they did not undertake multivariate analyses to examine sociological or psychological explanations for these sex differences. Although, they report that when asked about the causes of sleep difficulties, women were significantly more likely than men to perceive 'children' and 'partners' as causes of their sleep problems. Chen et al. (2006: 488) conclude that 'In contrast with explanations emphasising sex differences in biology and prior psychiatric illnesses, the sociological perspective has not been well investigated in the existing literature.' However, where more sociological explanations of sex differences have been considered, they have primarily been restricted to examining sex differences related to social roles (such as marital status, rates of participation in paid employment) and socio-economic status (SES) (Chen et al., 2006).

2.6 Chen et al. (2006) operationalised women's social roles by using marital status, employment status, and number of household members under 15 as a proxy for childcare responsibilities. They found that the sex difference in sleep disturbance was reduced after controlling for marital status, employment conditions, and number of children in the household, but women's sleep quality still remained significantly poorer than men's. This suggests the need for more refined measures of gender roles and responsibilities. Sekine et al. (2006) undertake such an analysis in their study of Japanese civil servants, analysing data on work characteristics, family characteristics and family-work conflicts. They show that the sex difference in reported quality of sleep among civil servants could be entirely explained by gender differences in work conditions, domestic roles and family-work conflicts, but this study relates only to a specific Japanese subgroup.

2.7 While epidemiological studies of sleep primarily focus on socio-demographic variables, such as gender, age and marital status (Lichstein et al., 2004), they also often collect data about shift work and work conditions, because of the recognised link between shift work and poor quality sleep. However, few studies address the broader socio-economic or family circumstances in which individual's lives are embedded. Some studies have collected data on educational qualifications and generally found that individuals with lower educational qualifications report poorer sleep (Moore et al., 2002; Klejna et al., 2003; Rocha et al., 2002), although Chen et al.'s (2006) national survey in Taiwan did not find increased sleep disturbance among those with less education.

2.8 Higher levels of sleep disturbance among people who are not working are reported in many studies. Rocha et al.'s (2002) research in Brazil found a higher prevalence of insomnia among individuals with lower levels of education, not working and with lower income, but they note that these relationships may be confounded by poor physical and mental health among those not employed and with lower socio-economic status.

2.9 Poor physical health is implicated in disrupted sleep, and one of the main reasons for poorer sleep quality with increasing age is because of chronic ill-health causing pain and discomfort at night, resulting in sleep complaints and disorders (Vitiello et al., 2002). Blaxter (1990) found a strong association between health status and reported duration of sleep; respondents with chronic conditions were more likely to sleep for less than 7 hours or more than 8 hours per night. However, this research examined duration rather than quality of sleep, and did not examine how socio-economic circumstances or gender roles were linked to sleeping patterns. It is important to assess whether any gender or socio-economic differences in sleep quality are because of poor physical health, and to conduct research including a more diverse range of measures of socio-economic circumstances, such as social class, income and housing conditions, as well as measures of gender roles.

2.10 Landis and Lantz (2006: 739) argue for 'multidisciplinary studies that take into account the gendered nature of women's multiple roles and responsibilities and how these impact on… poor sleep quality'. Our article provides one step in this direction by suggesting a more sociologically-informed quantitative approach to teasing out the impact of women's roles and relationships on their sleep, while also taking into account women's socio-economic characteristics and health status. Its focus on women over the age of 40 may help explain the high incidence of reported sleep problems in this age group.

Qualitative studies of women's sleep

2.11 Qualitative research on the sleep of midlife and older women has been pioneered by Hislop and Arber (2003a, 2003b, 2003c, 2006). Using focus groups, in-depth interviews and audio-sleep diaries, this corpus of work has produced insights showing the ways in which sleep is socially patterned and the impact of the family context on women's sleep. Central findings relate to how women's gender roles as care-taker for the well-being of their family, especially partner and children, disrupt their sleep. These roles are not restricted to the direct provision of care, such as attending to the physical needs of children at night, but fundamentally relate to women's engagement in the emotional labour of worrying about and anticipating the night-time needs of family members. This commitment to care for family members results in women's own sleep needs being de-prioritised (also see Bianchera and Arber's article in this issue).

2.12 Hislop and Arber's research shows how partners are the gatekeepers to the sleep resource for many women. Partner behaviour at night has a direct impact on the quality of women's sleep, particularly if their husband snores (see Venn's article in this issue). Women remain oriented to their partner's well-being during the night. Even when their husband's snoring is disturbing their own sleep, Venn shows how women develop complex yet subtle strategies to try to stop their partner snoring without waking him up. Similarly, husband's actions, such as going to the toilet during the night, coming to bed late and getting up early, may disturb women's sleep. Hislop (in this issue) examines the ways in which partners influence the nature of women's sleeping environment, highlighting the tensions and compromises inherent in accommodating individual sleep needs in a shared sleeping environment.

2.13 It is universally recognised and accepted that young children disrupt women's sleep, particularly when they are babies and require feeding or comforting during the night. The extent to which teenage and young adult children disrupt parent's sleep is less widely recognised. Our qualitative research showed that older children who are out at night, disrupt both mother's and father's sleep until they return home, because of safety concerns (Hislop and Arber, 2003a; Hislop et al., 2005; Venn et al forthcoming). Similarly, mother's sleep in Italy is disrupted by adult children not returning home until late at night (Bianchera and Arber's article in this issue). Although, qualitative research has identified older children as disrupting sleep in this way, how salient this is for the sleep of more representative samples of women with children remains unclear.

2.14 Sociological research has long identified that the work of caring involves not only practical aspects of caring for, but also the emotional aspects of caring about (Finch and Groves, 1982). The provision of emotional labour is therefore fundamental to caring (James, 1989, 1992). An integral part of this emotional labour has been characterised by Mason (1996) as 'sentient activity', which relates to thinking about, being alert to and recognising the needs and wants of those being cared for. Women are thus committed to the well-being of family members, both those living in their household, and adult children or elderly parents who are not co-resident, but nonetheless may be a concern for women, resulting in worries that disrupt their sleep at night. Stevens and Westerhof (2006) show how women are more likely to have worries about children, other family members and their partners than equivalent men in The Netherlands and Germany. It is therefore important when considering how gender roles impact on women's sleep, to include the 'work of worrying' about family members as a potential sleep disruptor, as well as the more direct ways in which partners and children may adversely interfere with women's access to the sleep resource.

2.15 Midlife for women is a time of the life course when the relational aspects of their lives provide particularly fertile ground for sleep disturbance, due to worries associated with caring for adult children, partners (who may have increasing health problems) and elderly parents, while the current generation of midlife women are also engaged in the institutional structures of paid work, with their attendant work-related stresses and concerns (Hislop and Arber, 2006). As well as sleep disturbance related to worries, women's sleep may be disrupted by their partners (given the increased incidence of snoring, prostate and other health problems with advancing age), and the night-time activities of teenage and young adult children. These factors all coalesce, together with the menopause and often women's own deteriorating health, leading to particularly high levels of sleep disruption at this stage of women's life course.

2.16 This article proposes a quantitative approach to assess the ways in which three central aspects of women's gender roles:- the night-time behaviours of their partners, night-time behaviours of their children, and night-time worries – impact on women's sleep, while at the same time considering how disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances and poor health may also compromise women's sleep. Through this analysis we assess the relative importance of each of these sets of factors in leading to sleep disruption among midlife and older women.

METHODS

3.1 The article draws on survey data collected in 2003 as part of an EU funded study on Women's Sleep in the UK1. Building on insights from our qualitative research, based on focus groups, in-depth interviews, and audio sleep diaries (Hislop and Arber, 2003a, 2003b, 2003c, 2006), a 12 page self-completion questionnaire survey was designed to collect information on the range of factors identified as influencing women's sleep in mid- and later life.3.2 The aim was to obtain a representative UK sample of women over age 40. A sample of 5142 women aged 35 and over was drawn from a database prepared by Business Lists UK, who specialise in the provision of mailing lists compiled using profile-based systems from a combination of the electoral register and other data sources in the public domain. Since this sampling frame had a minimum accuracy of 80-90% on the age selection, the selected minimum age was 35 (Hislop, 2004). After the initial questionnaire mail out and two follow-up reminders, a total of 1830 completed questionnaires were returned (plus 15 recorded as died), representing a response rate of 36%. Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias (1996) report a typical response rate for postal questionnaires without follow-ups of 20-40%. However, since the early 1990s there has been an increased reticence among the UK population to complete questionnaires and survey interviews; a factor which has led to declining response rates experienced by all survey organisations, including government surveys such as the General Household Survey (Walker et al., 2001; Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 1996).

3.3 The representativeness of the UK Women's Sleep Survey 2003 was assessed by comparisons with population data on women aged 40+ from the 2001 census and the 1999 British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) for the variables of age, marital status, education and social class (Hislop, 2004). Our sample matches the UK population of women over 40 fairly closely in terms of age, apart from a slight over-representation of women in the 50s and under-representation over age 70. There is also some under-representation of widows and those with poor educational backgrounds. In addition, we compared data from the Women's Sleep Survey with our (unpublished) secondary analyses of nationally representative data from the ONS Psychiatric Morbidity Survey for 2000 (Singleton et al., 2001), and found comparable results regarding how age, socio-economic circumstances and health status are associated with women's sleep quality. The ONS Psychiatric Morbidity Survey does not collect data on the night-time behaviours of partners and children, therefore to examine the impact of women's gender roles on their sleep, we analyse the Women's Sleep Survey 2003.

3.4 This article analyses the 1445 women aged 40 and over responding to the Women's Sleep Survey. Almost three-fifths (59%) were in midlife (aged 40-59), with 21% in their sixties and 20% over age 70, including a small number in their eighties. Nearly three-quarters were married or living with a partner, allowing a sufficient sample size to analyse how partner behaviours impact on women's sleep.

Measurement of sleep problems

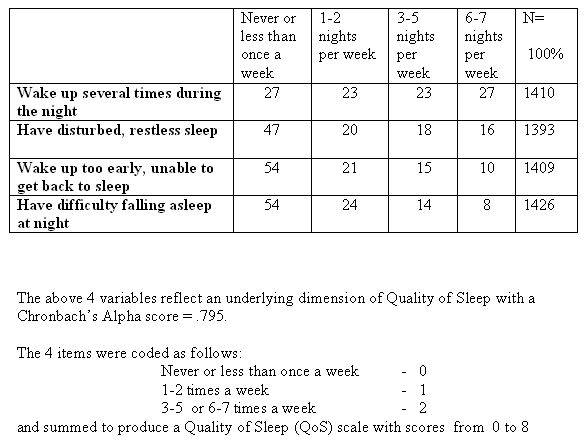

3.5 Women in the survey reported substantial night-time disturbance on four key aspects indicating quality of sleep, see Table 1. On three or more nights a week, half of women reported that they woke up several times during the night, a third reported disturbed or restless sleep, a quarter reported waking up too early in the morning and being unable to get back to sleep, and over a fifth had difficulty falling asleep. These findings therefore illustrate the high levels of sleep problems reported by midlife and older women in the UK.

| Table 1. Frequency of sleep problems reported by women aged 40 and over. (Row %) |

|

3.6 Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis showed that the four items in Table 1 loaded onto a single factor. Reported reliability based on Cronbach's Alpha for the factor was 0.795, indicating that the individual items were measuring the same construct with an acceptable level of reliability (see Bland and Altman, 1997). This construct was defined as Quality of Sleep (QoS). A QoS score was calculated by recoding the 4 items in Table 1 into 3 categories: reported sleep problem 'never or less than once a week' (code 0), reported sleep problem '1-2 times a week' (code 1), and reported sleep problems '3 or more nights per week' (code 2). The 4 items were then summed to produce a scale with values from 0 to 8 (mean = 3.5, standard deviation = 2.6). The Quality of Sleep (QoS) scale provides a measure of differences in sleep quality among women, with high values indicating greater sleep problems.

3.7 Our analysis uses the QoS scale as the dependent variable. The aim is to analyse how women's gender roles and responsibilities influence their quality of sleep (QoS) by assessing the impact of three aspects of women's family lives, namely the night-time behaviours of their partner, their children, and their worries and concerns. Each of these aspects is first explored and discussed using bivariate analysis based on Spearman's Rho for rank-ordered data. This is followed by analyses of all three aspects together within multivariate linear regression models to predict Quality of Sleep.

BIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF WOMEN'S QUALITY OF SLEEP

The impact of partners on women's sleep

4.1 Over four-fifths of midlife women (40-59) in the survey had a partner, but this fell to under half among women aged over 70, primarily due to increased widowhood with advancing age. Within our society it is normative for married women to share the same bedroom with their partner (see Hislop's article in this issue). Only 7% of midlife women slept in a different room from their partner, which increased to 18% among partnered women in their sixties and 25% over age 70. This age-related increase in partners sleeping separately probably reflects a loosening above age 60 of normative assumptions about partners sharing a bed together.4.2 Women were asked whether various night-time behaviours and activities of their partner had an adverse influence on their own sleep. These partner actions were raised as potentially disturbing factors by women in our qualitative research, and varied from snoring to reading in bed. Each partner behaviour was coded as disturbing women's sleep 'never', 'less than once a week', '1-2 nights a week', '3-5 nights a week', or '6-7 nights per week'.

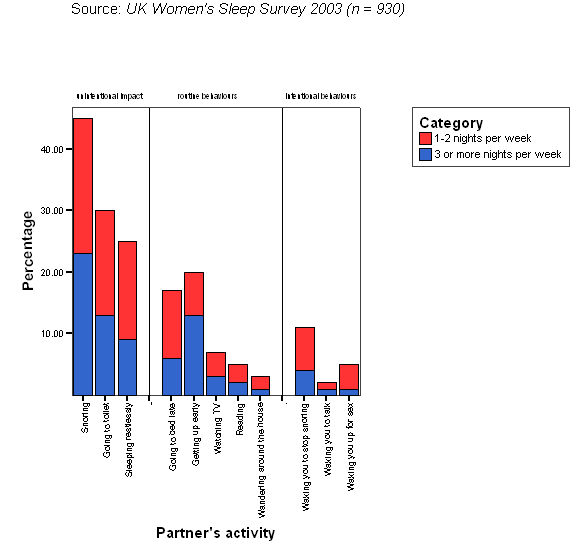

| Figure 2. % of women whose sleep is disturbed by partner behaviours |

|

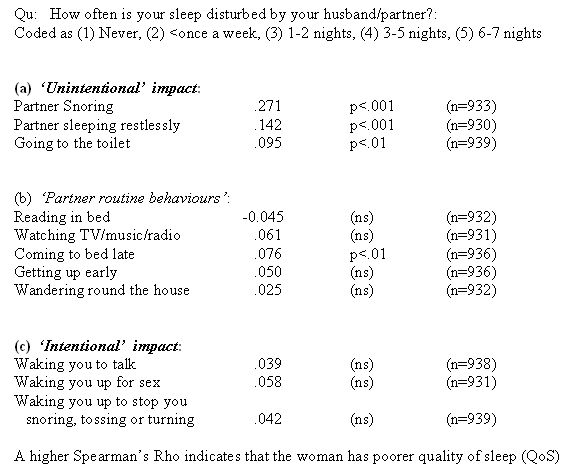

| Table 2. Correlations of women's Quality of Sleep (QoS) with partner's night-time behaviours. (Spearman's Rho) |

|

4.3 Figure 2 shows to what extent each partner behaviour disturbed women's sleep on 1-2 nights per week and on 3 or more nights per week. As suggested by our qualitative data, snoring was the partner behaviour with the greatest disruptive effect on women's sleep (also see Venn's article in this issue). Nearly half of partnered women (45%) had their sleep disturbed by their partner's snoring at least once a week, with a quarter saying that this occurred on 3 or more nights per week. Almost a third of women had their sleep disturbed at least once a week by their partner going to the toilet during the night, and over a quarter by their partner being restless (Figure 2). These three night-time partner behaviours are largely outside a husband's control, and therefore have an 'unintentional impact' on their wife. However, there may have been actions that their husband could take to minimise the sleep disruption that they cause their wife (see Venn's article in this issue). These three 'unintentional' partner behaviours all showed a highly significant correlation with women's sleep quality (QoS), with the strongest correlation (rho=.271, p<.001) between partner's reported snoring and women's quality of sleep (see Table 2).

4.4 A range of other partner actions, which are primarily within their partner's control, also had an impact on their wife's QoS. We have termed these 'routine' behaviours, for example, about a fifth of women had their sleep disturbed at least once a week by their partner getting up early, and a similar proportion were disturbed by their partner coming to bed late (Figure 2). Partners 'coming to bed late' had a significant correlation (rho=0.076, p<.01) with the quality of women's sleep (Table 2). This contrasts with activities such as partner reading in bed, which was unrelated to the quality of women's sleep.

4.5 In some cases, a woman's partner may intentionally disturb her sleep, for example waking her up to talk (reported by 2% at least once a week), and waking her up for sex (reported by 5% of partnered women at least once a week). In addition, male partners may wake their wife, because she is disturbing their sleep (see Venn's article in this issue); with 11% of women reporting that their partner woke them to stop them snoring, tossing or turning (at least once a week). We have characterised these three behaviours as men 'intentionally' disturbing their wife's sleep. However, while these behaviours may be a major cause of sleep disruption for the women affected, they occurred only among a small minority of women, and have a low and non-significant correlation with the overall quality of women's sleep (Table 2).

4.6 Our survey shows that the greatest impact that men have on their wife's sleep relates to 'unintentional behaviours', in particular snoring, but also restlessness at night and their partner getting up to go to the toilet.

The impact of children on midlife women's sleep

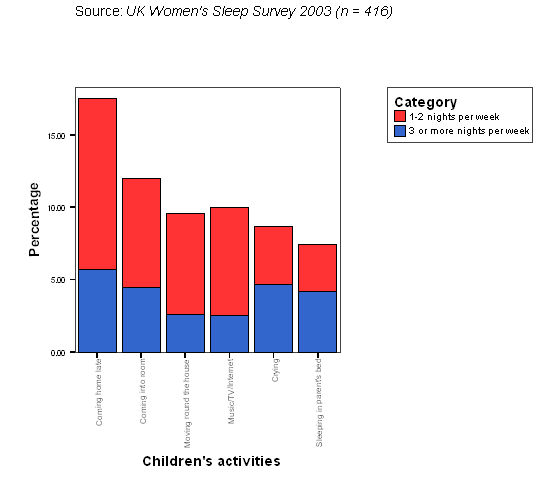

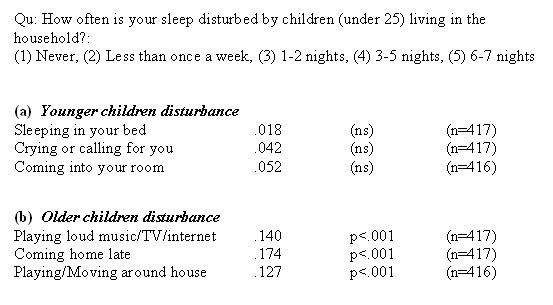

4.7 A third of women in the survey had children under age 25 living in the household. As expected, this varied from 75% of women in their forties to only 8% of women over age 60. Since our analysis focuses on women over age 40, only a minority had young children. Only 6% of women had any children under 10 years old, which was the case for 21% of women in their forties, but very few women over age 50. Therefore, in this sample of midlife and older women, we only expect a minor proportion of women's sleep disturbance to be due to younger children. This is indeed the case, Figure 3 shows that under 10% of women with children had their sleep disturbed by children 'crying out' or 'sleeping in their own beds'. Table 3 shows only modest and non-significant correlations between women's quality of sleep and children crying or calling during the night, coming into the parent's bedroom, and sleeping in the parent's bed.

| Figure 3. % of women whose sleep is disturbed by children's night-time behaviours |

|

| Table 3. Correlations of women's Quality of Sleep (QoS) with children's night-time actions – for women with children living at home (Spearman's Rho) |

|

4.8 As expected from our qualitative research (Hislop and Arber, 2003a), midlife women's sleep was disturbed to a greater extent by the night-time activities of older children. The major one was children coming home late, reported as disturbing their sleep by 18% of women with children (Figure 3). This showed a significant correlation with poor QoS (rho=0.174, p<.001). Parents, and particularly mothers, often have disturbed sleep when their adult children are out late, because of concerns about their child's safety, especially if they are driving. Parents often do not go to bed (or to sleep) until their teenage or adult child has returned home safely, or lie awake worrying in case their child has not returned, or get up during the night to check that the child has returned home (see also Bianchera and Arber's article in this issue). Older children cannot be 'put to bed' in the same way as younger children, and it is often a night-time concern of parents that their child is not going to bed until very late, or is playing loud music, watching TV, using the internet or playing computer games far into the night (reported by 10% of mothers as disturbing their sleep). A significant correlation between mother's quality of sleep and the latter activities of older children (rho=0.14, p<.001) is found (Table 3). In addition, mother's sleep may be disturbed by their children playing or moving around the house at night (rho=0.127, p<.001).

The impact of worries and concerns on women's sleep

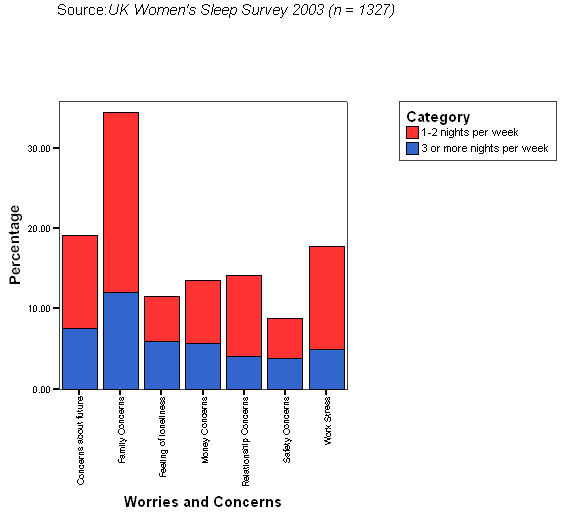

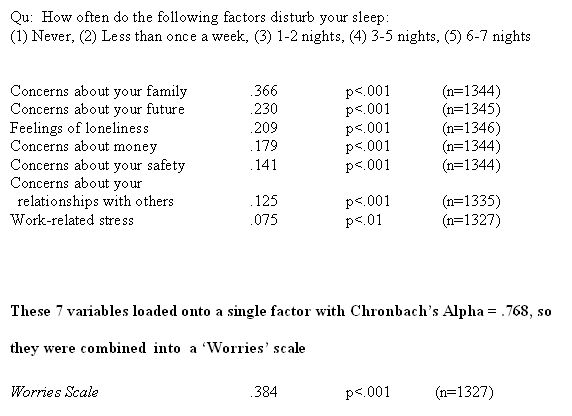

4.9 Women's sleep may be disrupted by being kept awake because of worries or concerns. This should not be seen as a mark of anxiety or psychological problems, but is intimately connected to the enactment of women's gender roles associated with emotional labour. A key part of women's lives is their responsibility for the well-being of family members, including not only those living in their household, but also children who have left home, elderly parents who may be in need of care, and extended family members. The emotional labour of being concerned about the well-being of family members is an integral part of the performance of women's gender roles (Mason, 1996).

| Figure 4. % of women whose sleep is disturbed by worries or concerns |

|

| Table 4. Correlations of women's Quality of Sleep (QoS) with reported concerns and worries (Spearman's Rho) |

|

4.10 Results from the present study confirm that worries and concerns have a major disruptive impact on women's sleep. The main worry that disturbs women's sleep is 'concerns about their family', reported by over a third of women (Figure 4), which also has the strongest correlation with women's Quality of Sleep (Table 4, rho=0.366, p<.001). This is followed by 'concerns about your future' (rho=0.23, p<.001), 'feelings of loneliness' (rho=0.209, p<.001) and 'concerns about money' (rho= 0.179, p<.001).

4.11 The extent to which different sorts of worries and concerns disrupt women's sleep is shown in Figure 4. These vary between life course stages, e.g. being kept awake at night by 'concerns about money' and 'work-related stress' was greatest for women in their forties and fifties (data not shown). In contrast, sleep disruption because of 'feelings of loneliness' and 'concerns about safety' increased linearly with age, especially above age 70 (Hislop, 2004). Concerns 'about your family' and 'about relationships' occurred among all women irrespective of their age, but were somewhat higher among women between 40 and 59.

Women's socio-economic circumstances, health and sleep

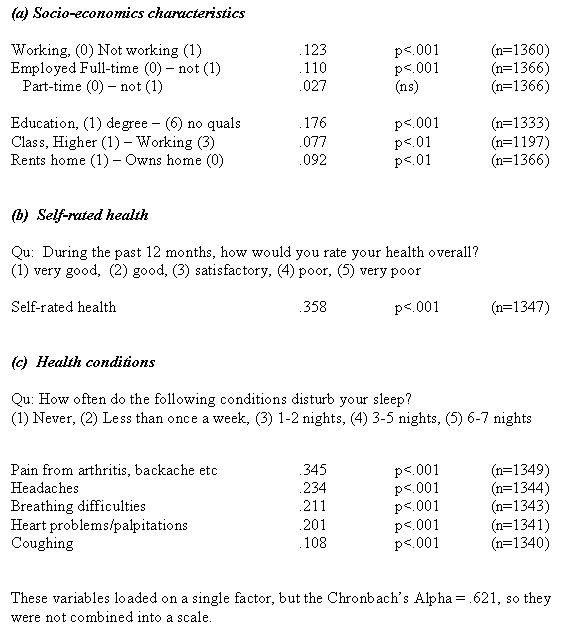

4.12 Midlife women often hold multiple roles as mother, carer and employee, which may impact on their sleep. There has been extensive research literature on to what extent women's multiple roles have adverse or positive effects on their health (Arber and Cooper, 2000; Lahelma et al., 2002), but no comparable literature in the sleep field. It is pertinent to consider how participation in paid work is associated with the quality of women's sleep. Women who are working report better quality sleep than those who are not working (Table 5a, rho=0.123, p<.001), but there is a non-significant correlation between quality of sleep and working part-time.

| Table 5. Correlations of women's Quality of Sleep (QoS) with women's socio-economic circumstances and health status (Spearman's Rho) |

|

4.13 Women enact their gender roles in varying material circumstances. We expect that those living in more disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances would report poorer quality sleep. This is indeed the case; the strongest correlation in Table 5a is between women's level of educational qualifications and their quality sleep. Women with higher educational attainment consistently report better quality of sleep (rho=0.176, p<.001). Although, only a minority of women in the survey are working, measuring their class based on their current (or previous) job showed that women in higher class occupations report better quality sleep than women (previously) in a working class job (rho=0.077, p<.01). Housing tenure may provide a more direct measure of quality of living circumstances; women living in owner occupied housing report better sleep than women who rent their accommodation (rho=0.092, p<.01).

4.14 Women's health status is also closely linked to their quality of sleep. Self-rated (or self-assessed) health is used extensively in research on inequalities in health, and is a good predictor of mortality and general health (Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Ferraro and Farmer, 1999). In the Women and Sleep Survey, there was a strong correlation between self-assessed health and women's Quality of Sleep (Table 5b, rho=0.358, p<.001). There were also substantial correlations between Quality of Sleep and women reporting that their sleep was disturbed by pain (from arthritis, backache, etc.) (rho=0.345, p<.001), from headaches (rho=0.234, p<.001) and from other health conditions (Table 5c).

4.15 Extensive research on inequalities in health has found that women who are not in paid work are more likely to be in poor health, and that disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances are linked to adverse health (Bartley et al., 1999; Arber and Cooper, 2000). Therefore it is important to assess to what extent there are independent effects of socio-economic circumstances and health status on women's quality of sleep, and whether these effects are additional to the effects on quality of sleep of night-time behaviours of partners, children, and worries.

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSES OF WOMEN'S QUALITY OF SLEEP

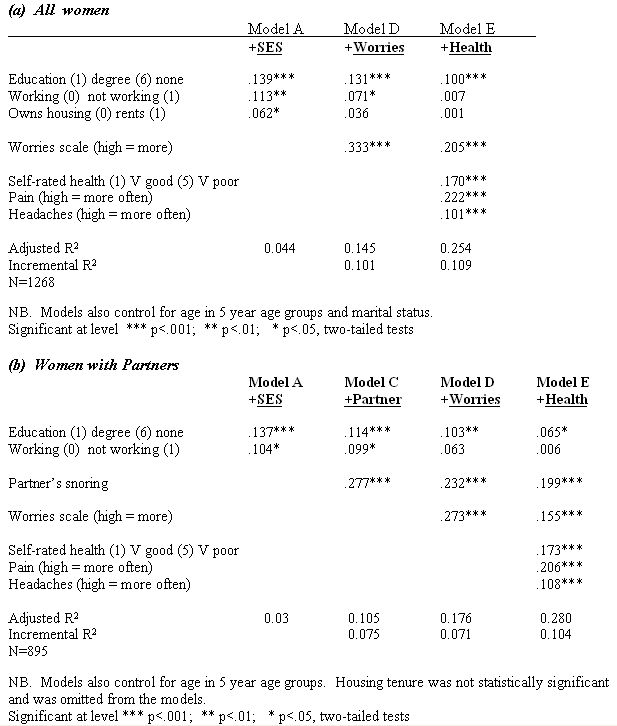

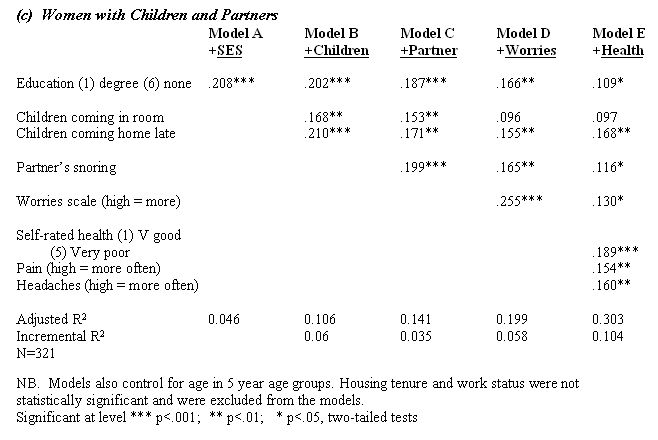

5.1 We have shown that women's quality of sleep is associated with their gender roles as family carers, partners and parents, as well as their role as a paid worker, their socio-economic circumstances and health status. Given these associations, hierarchical multiple regression techniques were employed to ascertain the relative predictive importance of the various types of independent variables, particularly the relative influence of partner's night-time behaviours, children's night-time behaviours, and women's worries and concerns. We examine how each of these aspects of women's gender roles influence their quality pf sleep, and whether these effects are mediated by socio-economic circumstances and health status. Three separate hierarchical multiple regression analyses of women's Quality of Sleep are presented in Table 6: for all women (n=1268), for women with partners (n=895), and for partnered women with children (up to age 25) living at home (n=321).5.2 In each case, the first model (Model A) includes socio-economic circumstances, as well as age (in 5 year age groups) and marital status. NB. Age and marital status were not statistically significant in the models and are not presented in Table 6. For partnered women (Table 6b), the regression analyses include the partner variables displayed in Table 2 that had statistically significant effects (in Model C). For partnered women with children (Table 6c), the regression analyses include those child variables displayed in Table 3 that had significant effects (in Model B), together with partner variables (in Model C). In each case, the penultimate model (Model D) includes a Worries Scale constructed by summing the seven items described in Table 4. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the seven items listed in Table 4 all loaded onto a single factor. Reported reliability based on Cronbach's alpha for the Worries factor was 0.768. The final model includes self-assessed health and the health problems displayed in Table 5, which had a significant effect when entered into Model E.

| Table 6. Hierarchical Multiple regression models of women's Quality of Sleep (QoS) – beta coefficients |

|

Women's sleep – worries, socio-economic status and health status

5.3 First, all women over 40 are analysed to assess the effects of worries, socio-economic circumstances and health on quality of sleep (QoS) (Table 6a). As indicated by the R2 in the final model, 25% of the variance in women's quality of sleep can be accounted for by these variables.

5.4 Socio-economic circumstances have a significant impact on women's sleep, explaining 4.4% of the variance in QoS (Model A). Women who are more educated report significantly better quality sleep, as do women who are currently employed and who own (rather than rent) their home. Thus, women living in disadvantaged socio-economic circumstances report poorer quality sleep.

5.5 The addition of the Worries Scale in Model D has a substantial effect, increasing the explained variance in women's sleep quality to 14.5%, demonstrating that women reporting greater worries, anxieties and concerns about their family, relationships and future circumstances have poorer quality sleep. Our findings suggest that Worries, which are closely linked to women's gender role, have a strong association with quality of sleep (β=0.333 in Model D). Once the Worries Scale is included in Model D, there is a reduction in the strength of the standardised regression (β) coefficient of housing tenure, which is no longer statistically significant, and that for work status decreases. These findings suggest that a proportion of the worries that disrupt women's sleep are related to their poorer material circumstances (or not being employed). However, the impact of Worries is independent of educational level, since the β coefficient for education remains unchanged in Model D.

5.6 The greatest increase in explained variance occurred when health variables were added in the final model (Model E), increasing the explained variance from 14.5% to 25.4%. Standardized regression coefficients (β) in the final model illustrate that experiencing pain at night has the greatest association with sleep quality (β=0.222), and that self-reported health (β=0.17) and experiencing headaches (β=0.101) are also important predictors of women's quality of sleep. Poorer health status is the reason for the worse QoS of women who are not in paid work and women who live in rented housing, since in both cases the beta coefficients reduce to zero when the health status variables are included in Model E.

5.7 In many respects these results are not surprising: women experiencing more pain, headaches and worries, and suffering from poorer health, report worse quality of sleep. What is perhaps more surprising is that educational qualifications continue to have a substantial relationship with women's QoS, even after health is included in the final model (β=0.10). Although, it is not possible to be clear about the direction of causality between poor self-reported health and sleep quality, since women who are chronically over-tired because of disrupted sleep may report poor self-assessed health, it is not tenable to argue for reverse causation between poor sleep quality and low education.

Women with partners

5.8 The second set of multiple regression analyses relate to women with partners (n=895) and assess whether partner's night-time behaviours influence the sleep quality of partnered women, while also examining the impact of worries, socio-economic circumstances and health status (Table 6b).

5.9 Table 2 showed that four partner behaviours had significant correlations with women's quality of sleep. However, when these partner behaviours were entered into Model C (after including socio-economic variables and age in the model), only partner's snoring had a statistically significant association with women's quality of sleep. The impact of snoring was substantial, resulting in a 7.5% increase in explained variance, and β=0.277.

5.10 Worries about family, relationships and other concerns also had a substantial association with partnered women's QoS, explaining an additional 7% of the variance (Model D). A similar pattern of relationships between women's health status and quality of sleep was found for partnered women in Model E, as for all women in Table 6a.

5.11 The R2 in the final model, indicates that 28% of the variance in partnered women's quality of sleep is accounted for by these independent variables. The most important variables within the final model were pain (β=0.206), partner's snoring (β=0.199), self-rated health (β=0.173) and worries (β=0.155). It is notable that the addition of partner's snoring continued to have a substantial impact on women's quality of sleep, even after including all the other variables in Model E. However, employment status was confounded by covariants such as worries, self-rated health and experiencing pain.

Women with children

5.12 The final analysis examines the association between all three family-related factors, namely, children, partners and worries, and women's sleep (Table 6c), and is restricted to partnered women with children living at home (n=321). It therefore focuses on a subset of primarily midlife women, since over 60% of women with children are in their forties. The educational level of partnered women with children is strongly associated with their sleep quality (β=.208), but there was no significant association between employment status or housing tenure and their quality of sleep.

5.13 When the children's night-time behaviour variables displayed in Table 3 were entered into the multiple regression in Model B, only 'children coming home late' and 'children coming into the parent's bedroom' were significantly associated with women's QoS (β of 0.21 and 0.168 respectively). The addition of these two child variables into the model increased the explained variance by 6%. Our findings therefore suggest that children have a substantial impact on midlife women's self reported quality of sleep. This may seem uncontroversial, but some sleep researchers have suggested that there is no relationship between number of children and women's reports of fatigue and tiredness (Haglow et al., 2006).

5.14 Partner's snoring was also an important predictor of mother's sleep quality (β=0.199) in Model C. The inclusion of partner's snoring in Model C had only a modest moderating effect on the beta coefficients of the child night-time behaviour variables with QoS. Worries and concerns at night also had a major association with women's sleep (β=0.255), explaining an additional 6% of the variance in QoS.

5.15 The final model shows that 30% of the variance in the sleep quality of partnered women with children can be accounted for by their education, child behaviour variables, partner's snoring, worries and health related variables. Three health variables were significant in the model, explaining an additional 10.4% of variance. The most important predictor of QoS was self-rated health (β=0.189). It is notable that for these women, who were primarily in their forties, the pattern of association of the three health variables differed somewhat from the earlier analyses (in Tables 6a and 6b), with the largest beta coefficients for self-rated health, followed by headaches (β=0.16) and then pain (β=0.154). This was expected, as fewer midlife women with children have chronic illnesses resulting in pain that disturbs their sleep than among older women. Self-assessed health, measured on a 5 point scale from very good to very poor health, has the strongest association with their sleep quality. However, as noted earlier, it is not possible to disentangle whether poor self-assessed health leads to disrupted sleep or vice versa.

5.16 Interestingly, the child variables were partially confounded with the Worries covariant. The inclusion of the Worries Scale reduced the association between the item 'children coming into the room at night' and QoS, suggesting that some of the worries of women at night may be linked to the night-time behaviours of their children, which are manifest in children disturbing their parents' sleep by coming into their room. However, the beta coefficient for 'children coming home late' was only marginally reduced, suggesting that the Worries Scale is tapping other factors separate from concerns about the safety and well-being of teenage and adult children out at night. The impact of 'children coming home late' remains substantial in the final model (β=0.168), indicating that this has an important independent effect on the quality of women's sleep.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

6.1 This article has examined midlife and older women's self-reported quality of sleep, using sociologically informed quantitative analysis. Drawing upon survey data collected from 1445 women aged over 40, and using both bivariate and multivariate analysis, we have illustrated the importance of women's gender roles in influencing the quality of their sleep. Although, the response rate of 36% was disappointing, it is in line with other mail surveys of midlife and older people, e.g. Robertson and Warr (2002) in a postal survey of 3500 people aged 50-75 years on experiences of paid work report a response rate of 34% (which they considered 'healthy'), and Gilhooly's (2002) study of transport and ageing involving a postal survey of 5000 people achieved a response rate of 23%. These surveys were comparable in scope to that used in this study. Comparisons with our own analyses of the nationally representative Psychiatric Morbidity Survey found similar patterns of relationships between socio-demographic variables and sleep quality, reinforcing confidence in the robustness of our sleep measure and the findings reported in this article.6.2 Our findings reinforce notions that sleep disruption is a common part of women's lives. On three or more nights a week, half of women reported that they 'woke up several times during the night', a third reported 'disturbed or restless sleep', a quarter reported 'waking up too early in the morning and being unable to get back to sleep', and over a fifth had 'difficulty falling asleep'. Reliability analysis showed that these four items reflected an underlying dimension of poor sleep quality.

6.3 Women's sleep is both embodied and embedded within their social roles and responsibilities. Our findings should be seen alongside existing qualitative research, for example, adding weight to Hislop and Arber's (2003a, 2003b; Venn et al forthcoming) suggestion that women continue to undertake emotional labour and sentient activity during the night. For women, worries and concerns about family, relationships and other matters represent an important predictor of poor sleep quality. Within previous sleep research, which has been heavily slanted towards physiology and the life sciences, there has been a tendency to view 'worries' as a mark of psychological problems. However, the present study indicates that worries related to such things as 'concerns about your family' and 'finances' disrupt women's sleep. Within the hierarchical regression models 'worries' were confounded with covariants such as child night-time behaviours and socio-economic circumstances. These findings suggest that living in rented housing is linked to poor quality sleep through Worries, and that at least some of the concerns troubling women at night are associated with the night-time behaviours of their children.

6.4 Findings also offer support to the notion that women's sleep is adversely affected by their partner's and children's night-time behaviours (Hislop and Arber, 2003a). A strong predictor of poor quality sleep was their partner's snoring. Snoring has a major influence on women's sleep but needs to be viewed as linked to issues of power within the couple. As Venn (this issue) suggests, within a couple situation snoring is a complex, multifaceted event involving, both structural constraints and embodied (gendered) agency. How disturbance due to snoring is managed may be linked into the ways couples negotiate their sleep (explicitly or implicitly) and the disturbances which women 'allow' to continue.

6.5 Through a sociologically informed quantitative approach, the present study goes beyond existing qualitative and quantitative research by examining the relative importance of different sets of factors in leading to sleep disruption among women in mid and later life. The key factors implicated in the poor quality sleep of midlife and older women are their partner's snoring, night-time worries and concerns, poor health status (especially experiencing pain at night), disadvantaged socio-economic status (especially having lower levels of education) and for women with children, their children coming in late at night. However, using cross-sectional survey data it is not possible to determine directions of causality. We acknowledge that in relation to the association between sleep and health, severely disrupted sleep may lead to reporting poor self-assessed health, as well as poor health having a direct adverse effect on sleep quality as suggested by other authors (Blaxter, 1990; Vitiello et al., 2002).

6.6 Our approach has allowed examination of predictors of women's quality of sleep which may be confounded with other covariants, as well as the strength of predictors in combination with other factors. Work status, for example, appears to play a role in women's self reported quality of sleep but, primarily through its intrinsic relationship with worries and women's health status. In this vein, the relationship between education and quality of sleep is also of note. Rocha et al.'s (2002) research in Brazil found a higher prevalence of insomnia among individuals with lower levels of education, who were not working and who had lower income, and suggest that these relationships may be confounded by poor physical health. In contrast, within our study educational qualifications continue to have a substantial relationship with women's QoS even after health, worries, partner and children variables are controlled for. We suggest two possible explanations. First, that women with higher educational qualifications live in more advantaged material circumstances, which were not captured by other socio-economic variables included in our models. Second, more educated women may have better knowledge about practices that can be used to improve sleep, and are more proactive in their attempts to use various personalised strategies to enhance the quality of their sleep (Hislop and Arber, 2003c).

6.7 Finally, our research demonstrates that women are not a homogenous group and it is important to consider how position in the life course influences women's sleep. Health status, for example, was an important predictor of quality of sleep for all women, but the strength of the relationships varied between those with children and all women over age 40. Women's sleep is clearly a complex and multifaceted phenomenon (Williams, 2002, 2005). This article has provided an illustration of how a quantitative approach can be used to capture aspects of the gendered nature of women's multiple roles and responsibilities and how these coalesce resulting in poor sleep quality for many women in mid and later life.

Notes

1 The authors are grateful for funding from the European Commission, contract numbers QLK6-CT-2000-00499 and MRCTN-CT-2004-512362.

References

ARBER, S. and Cooper, H. (2000) 'Gender and inequalities in health across the life course'. In E. Annandale and K. Hunt (editors) Gender Inequalities in Health, Buckingham: Open University Press.

BARTLEY, M., Sacker, A., Firth, D. and Fitzpatrick, R. (1999) 'Social position, social roles and women's health in England: Changing relationships 1984-1993', Social Science and Medicine, 48: 99-115.

BIANCHERA, E, and Arber, S. (2007) Caring and Sleep Disruption Among Women in Italy, Sociological Research Online, Volume 12 Issue 5 http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/4.html

BLAND, J., M. and Altman, D. G. (1997) 'Statistics Notes: Cronbach's alpha', British Medical Journal 314:572

BLAXTER, M. (1990) Health and Lifestyles, London: Routledge.

BRESLAU, N., Roth, T., Rosenthal, L. and Andreski, P. (1996) 'Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults', Biological Psychiatry, 39: 411-18.

CHEN, Y-Y., Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S.V., Acevedo-Garcia, D. and Lee, Y-J. (2005) 'Can social factors explain sex differences in insomnia? Findings from a national survey in Taiwan', Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59: 488-494.

DZAJA, D., Arber, S., Hislop, J., Kerkhofs, M., Kopp, C., Pollmacher, T., Polo-Kantola, P., Skene, D., Stenuit, P., Tobler I. and Porkka-Heiskanen T. (2005) 'Women's sleep in health and disease', Journal of Psychiatric Research, 39: 55-76.

FERRARO, K. and Farmer, M. M. (1999) 'Utility of health data from social surveys: Is there a gold standard for measuring morbidity?' American Sociological Review, 64: 303-315.

FINCH, J. and Groves, D. (1983) A Labour of Love: Women, Work and Caring, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

FRANKFORT-NACHMIAS, C. and Nachmias, D. (1996) Research Methods in the Social Sciences (5th edition). London: Arnold.

GILHOOLY, M. (2002) Transport and ageing: Extending quality of life for older people via public and private transport, ESRC End of Award Report. (ESRC award ref: L480 25 40 25). 31 May 2002.

GROEGER, J, Zilstra, F and Dijk, D-J. (2004) 'Sleep quantity, sleep difficulties and their perceived consequences in a representative sample of some 2000 British adults', Journal of Sleep Research, 13: 359-371.

HAGLÖW, J., T., Lindberg, E., and Janson, C. (2006) 'What are the important risk factors for daytime sleepiness and fatigue in women?' Sleep, 29(6): 751-757.

HISLOP, J. (2004) 'The Social Context of Women's Sleep: Perceptions and Experiences of Women Aged 40 and Over'. Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Sociology, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK.

HISLOP, J. and Arber, S. (2003a) 'Sleepers wake! The gendered nature of sleep disruption among mid-life women'' Sociology, 37 (4): 695-711.

HISLOP, J. and Arber, S. (2003b) 'Sleep as a social act: A Window on gender roles and relationships' in S.Arber, K. Davidson and J. Ginn (editors) Gender and Ageing: Changing Roles and Relationships, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

HISLOP, J. and Arber, S. (2003c) 'Understanding Women's sleep management: beyond medicalisation-healthisation?', Sociology of Health & Illness, 25(7): 815-837.

HISLOP, J., Arber, S., Meadows, R. and Venn, S. (2005) 'Narratives of the Night: The Use of Audio Diaries in Researching Sleep', Sociological Research Online, 10(4): <http://www.socresolnline.org.uk/10/4/hislop.html >.

HISLOP, J. and Arber, S. (2006) 'Sleep, gender and ageing: Temporal perspectives in the mid-to-later life transition'. In T M. Calasanti and K F. Slevin (editors) Age Matters: Realigning Feminist Thinking, New York: Routledge.

HISLOP, J. A Bed of Roses or a Bed of Thorns? Negotiating the Couple Relationship Through Sleep, Sociological Research Online, Volume 12 Issue 5 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/2.html>

IDLER, E.L. and Benyamini, Y. (1997) 'Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies', Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 38: 21-37.

JAMES, N. (1989) 'Emotional labour: skill and work in the social regulation of feelings', Sociological Review, 37, 15-42.

JAMES, N. (1992) 'Care = organisation + physical labour + emotional labour', Sociology of Health & Illness, 14(4): 488-509.

KIETJNA, A., Wojtyniak, B., Rymaszewska, J. and Stokwiszewski, J. (2003) 'Prevalence of insomnia in Poland – results of the National health Interview Survey', Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 15: 68-73.

LAHELMA, E., Arber, S., Kivela, K. and Roos, E. (2002) 'Multiple roles and health among British and Finnish women: The influence of socioeconomic circumstances', Social Science and Medicine, 54 (5): 727-740.

LANDIS, C.A. and Lentz, M. J. (2006) 'Editorial: News alert for mothers: Having children at home doesn't increase your risk for severe daytime sleepiness ad fatigue', Sleep, 29 (6): 738-740.

LICHSTEIN, K., L., Durrence, H., H., Riedel, B., W., Taylor, D., J. and Bush, A., J. (2004) Epidemiology of Sleep: Age, Gender and Ethnicity, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London.

LINDBERG, E., Janson, C., Gislason, T., Bjornsson, E., Hetta, J. and Boman, G. (1997) 'Sleep disturbances in a young adult population: Can gender differences be explained by differences in psychological status', Sleep, 20: 381-7.

MANBER, R. and Armitage, R. (1999) 'Sex, steroids and sleep: A review', Sleep, 22: 540-55.

MASON, J. (1996) 'Gender, care and sensibility in family and kin relationships' in J. Holland and L. Adkins (editors) Sex, Sensibility and the Gendered Body, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

MOORE, P.J., Adler, N.E., Williams, D.R. and Jackson, J.R. (2002) 'Socioeconomic status and health: the role of sleep', Psychosomatic Medicine, 64: 337-44.

PICCINELLI, M. and Wilkinson, G. (2000) 'Gender differences in depression: critical review', British Journal of Psychiatry, 177: 486-92.

ROBERTSON, I. and Warr, P. (2002) Older people's experiences of paid employment: Participation and quality of life, ESRC End of Award Report. (ESRC award ref: L480254032), 31 May 2002.

ROCHA, F.L., Guerra, H.L., Fernanda, M. and Lima-Costa, F. (2002) 'Prevalence of insomnia and associated socio-demographic factors in a Brazilian community: the Bambui study', Sleep Medicine, 3: 121-6.

SEKINE, M., Chandola, T., Martikainen, P., Marmot, M. and Kagamimori, S. (2006) 'Work and family characteristics as determinants of socioeconomic and sex inequalities in sleep: The Japanese Civil Servants Study', Sleep¸29(2): 206-216.

SINGLETON, N., Bumpstead, R., O'Brien, M., Lee, A. and Meltzer, H. (2001) Psychiatric Morbidity among Adults living in Private Households, 2000, Office for National Statistics, London: The Stationery Office.

STEVENS, N. and Westerhof, G.J. (2006) 'Marriage, social integration, and loneliness in the second half of life', Research on Aging, 28 (6): 713-729.

USTUN, T.B. (2000) 'Cross-national epidemiology of depression and gender', Journal of Gender Specific Medicine, 3: 54-8

VENN, S. (2007) 'It's Okay for a Man to Snore': the Influence of Gender on Sleep Disruption in Couples, Sociological Research Online, Volume 12 Issue 5 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/1.html>

VENN. S., Arber, S., Meadows, R. and Hislop, J. (forthcoming) ‘The Fourth Shift: Exploring the gendered nature of sleep disruption in couples with children’, British Journal of Sociology .

VITIELLO, M.V., Moe, K.E. and Prinz, P.N. (2002) 'Sleep complaints cosegregate with illness in older adults. Clinical research informed by and informing epidemiological studies of sleep', Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53: 555-559.

WALKER, A., Mahler, J., Coulthard, M., Goddard, E. and Thomas, M. (2001) Living in Britain. Results from the 2000/01 General Household Survey. London: The Stationery Office.

WILLIAMS, S. (2002) 'Sleep and health: Sociological reflections of the dormant society', Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 6 (2): 173-200.

WILLIAMS, S. (2005) Sleep and Society: Sociological Ventures into the (Un)known, London: Routledge.

ZHANG, B. and Wing, Y-K. (2006) 'Sex differences in insomnia: A meta-analysis'¸ Sleep, 29(1): 85-93.