Social Change and the Family

by Chris Harris, Nickie Charles and Charlotte Davies

University of Wales Swansea, University of Warwick, University of Wales Swansea

Sociological Research Online, Volume 11, Issue 2,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/2/harris.html>.

Received: 6 Oct 2005 Accepted: 16 Feb 2006 Published: 30 Jun 2006

Abstract

This paper explores the social change of the past 40 years through reporting the results of a restudy. It argues that social change can be understood, culturally, as involving a process of de-institutionalisation and, structurally, as involving differentiation within elementary family groups as well as within extended family networks. Family change is set in the context of changes in the housing and labour markets and the demographic, industrial and occupational changes of the past 40 years. These changes are associated with increases in women's economic activity rates and a decrease in their 'degree of domesticity'. They are also associated with increasing differentiation within families such that occupational heterogeneity is now found at the heart of the elementary family as well as within kinship groupings as was the case 40 years ago. Thus the trend towards increased differentiation identified in the original study (Rosser and Harris: The Family and Social Change) has continued into the 21st century. This is associated with a de-institutionalisation of family life and an increasing need for partners to negotiate participation in both productive and reproductive work.

Keywords: De-Institutionalisation, Social Change, Restudy, Occupational Differentiation, Extended Family

Introduction

1.1 As long ago as 1999, Grundy, Murphy and Shelton in an article in Population Trends, presented findings which demonstrated that the relationships formed within families between parents and children persisted throughout life. This was evidenced by high rates of contact between members of households of different generations in spite of the increased geographical dispersion of the members of such networks. Such parent-adult child relations form the key links of an extended kin network comprising those kin who in other times and societies would have tended to form a residential group or 'extended family'. The preliminary results of our re-study of the family and social change in Swansea (Charles, Davies and Harris 2003) also demonstrated the remarkable resilience of extended family groupings. This may have been a surprise to any sociologists who had unthinkingly assumed that the decline in the proportion of households formed by nuclear families indicated a decline in the importance of the nuclear family in a more general sense. Be that as it may, our findings were certainly not news to those familiar with the empirical evidence on this issue.1.2 In this paper our focus is on the character of the social change experienced over the last 40 years by Wales's second city and how this relates to family change. Our argument is that during this period social change can be understood, culturally, as involving a process of de-institutionalisation and, structurally, as involving differentiation within elementary family groups as well as within extended family networks. In the first part of the paper we attempt to specify the degree and character of social change, with brief reference to Swansea's labour and housing markets. We then describe the demographic, industrial and occupational changes that have taken place in Swansea, and their consequences. In so doing we draw out the relation of these changes to changes in women's domesticity and economic activity. Finally we discuss the increasing heterogeneity of the kin universes of individuals and, particularly, the differentiation that can now be found within the elementary family, specifically within couples.

The two studies

2.1 The 2002 Swansea study is, as far as possible, a replication of the study of family and kinship in the town of Swansea undertaken by an anthropologist and a sociologist in 1960 (Rosser & Harris, 1965). It consists of a 1000-household survey of individuals selected randomly from the electoral register and interviewed between May and September 2002. It also involves 3 ethnographic studies of different areas of Swansea. [1] Here we draw only on findings from the survey.2.2 The original 1960 study was not confined to data on family formation and kin relationships but, by deploying economic, demographic, geographical and historical data, it attempted to paint a picture of the town as a social totality. In this it followed its predecessor whose conclusions it was designed to test. Its predecessor was Michael Young and Peter Willmott's now classic study of Bethnal Green entitled Family and Kinship in East London (1957) which generations of readers have interpreted as being 'about' the 'mum', i.e. about the mother-centred family life in the East End of London. Michael Young is reported to have described the study as being about 'planning'. These two interpretations are in no way inconsistent. Young and Willmott showed the way in which related working class family households in the East End were dependent on each other for their survival and were fearful of the failure of 'planners' to understand the social implications of the revolutionising of the built environment, namely the disruption of family support networks.

2.3 In 1955 'the Bethnal Green family' was only as it was in and through its relationships to other social institutions: the docks board which mediated its relationship to paid work and the local housing authority which through slum clearance and council housing was increasingly mediating the family's relationship to domestic accommodation. Today the docks, never mind the bureaucracy which administered them, have gone and a whole range of factors, geographical, political and economic has, through the transformation of the built environment, greatly altered the relation of 'the Bethnal Green family' to the supply of housing. Today we should say that, in both Swansea and Bethnal Green, 'the local family' is what it is in and through its relation to the local housing market and the local labour market.

2.4 The 1960 Swansea study's 'anthropological' approach followed on easily enough from Young's 'planning' approach. Young and Willmott were concerned primarily with one specific change: the out migration of population to a remote housing estate. The Swansea study in contrast was centrally concerned with more general social change: the social changes that had occurred between the social world in which Swansea's 1960s old age pensioners had been raised (1880 – 1900) and the brash modern world of the fifties with which the Swansea equivalent of Bethnal Green's 'mum'-centred extended families had to cope. The way the authors of the original Swansea study summed up these changes was by employing the contrast between a 'stable' and a relatively homogeneous society and a 'mobile' and (on virtually all dimensions) heterogeneous one. The family was (in effect) a microcosm of society in so far as the cultural, occupational, linguistic and geographical mobility of younger generations within the family meant that the social solidarity of the three generational kin group had been seriously weakened.

2.5 The strongest links in the traditional Swansea family had been, as in Bethnal Green, between mothers and married daughters leading to an uxori (wife)-local residence pattern. What flowed along these links was the exchange of domestic services and this was possible because of the high degree of what Rosser and Harris called the 'domestication of women'. The level of female domestication was for these authors a critical variable in understanding differences in family structure and behaviour.

The critical factor in both the nature of the marital relationship and in the internal organisation of the elementary family and also in the 'connectedness' of the external kinship networks is the degree of domesticity of the women involved. (1965: 208)However the cumulative effect of demographic changes (between 1900 and 1960) had been

to produce a relatively sudden and revolutionary change in the social position of women……. The trend of familial change is away from the former compulsive domesticity of women and thus away from 'segregated' marital relationships and 'close-knit' networks in the direction of 'joint' marital roles and 'loose-knit' networks. (1965: 209; cf. Bott 1957:56)

2.6 This trend was obviously accentuated by the white goods revolution: in 1960 ownership of refrigerators and washing machines was spreading fast but had yet to become as it is today almost universal. As the burden of domestic labour was eased so the need of households for support from other households diminished. At the same time it became possible for married women to combine part time employment with their domestic activities. In 1960 the supply of domestic services by women both in and between households was not yet seriously impeded by female employment. Young women went out to work before they got married and older women were increasingly going out to work after their children had left school, but frequently only part time (Rosser and Harris, 1965, pp. 77-9).

2.7 The authors of the original study recognised that demographic change was both cause and effect of the decline in women's domestication. They did not however recognise that the decreasing domestication of women was an effect as well as a cause of the increasing entry of women into paid employment and that the transformation of the labour market was to play a similar role in the transformation of family life in the second part of the twentieth century to that played by demography in the first. In what follows we attempt to specify these transformations and their impact on differentiation within families and kinship networks, arguing that a major change is the increasing and now high levels of occupational heterogeneity within elementary families.

Part One: Social change in Swansea, 1960 – 2000: an overview

3.1 The transformations of the labour and housing markets since 1960 create a number of difficulties for a re-study. There are obviously problems of comparison, but the difficulties with which we are concerned in this paper are those of characterising the nature of these wider social changes which have taken place in Swansea (as elsewhere) as they affect family relationships and behaviour. These wider social changes are, we believe, of a different order from those, enormous though they were, which took place from 1900 to 1960.Class

3.2 In 1900 the class system had at its base two fundamental distinctions: those who worked for a living and those who didn't and, among those who worked, those who worked with their hands and those who didn't. The manual non-manual divide was absolutely fundamental and virtually defined what being 'middle class' or 'working class' meant. This division was expressed in dress so that class membership was instantly recognisable and interaction in public places was segregated according to these visible signs of class membership. In this sense, though the proportions had changed and wage differentials had changed (see Atkinson 2000 in Halsey and Webb 2000), 1900 and 1960 societies were societies that shared a major social division based on this distinction. This is no longer the case.

3.3 In 1960 it was possible to claim that sociologists had only one explanatory variable: 'class'. This is also no longer true. These two changes are related. It does not follow that hierarchical differentiation is any less important in explaining people's social behaviour or any less important an element of social structure. But at the structural level the locations of hierarchical distinctions have changed, as has the size of the groups that are demarcated by them, and at the level of social action and consciousness class distinctions are no longer signified by institutionalised differences in speech and behaviour in the way that that they were in 1960.

Industrial change

3.4 In industry, too, vast changes occurred during the first half of the century but those occurring between 1960 and 2000 were of a different kind. Between 1900 and 1960 a multitude of small metal manufacturing plants in Swansea and its nearby valleys had been replaced by the building of three large-scale modern plants outside Swansea County Borough. The largest, situated nine miles east of Swansea, became the work place of most of Swansea's steel workers many of whom, at the turn of the century, had walked to work. Modern manufacturing methods had massively reduced the burden of manual labour from its 1900 levels and resulted in improved working conditions and high levels of wages.

3.5 These were all major changes. However manufacturing processes in 1960 were, by today's standards, still relatively labour intensive. Between1960 and 2002 this has ceased to be the case (Harris et al.,1987). In 1961 manufacturing accounted for a quarter of Swansea's work force (Census 1961); today it constitutes little over a tenth (ONS, 2002). (The corresponding figures for Britain are: 1966 33% 1991 20% (Gallie in Halsey, 2000)). In 1960 as in 1900 it was still true that the majority of the working population was 'traditional working class' in as much as it was male, manual and worked in the industrial sector of the economy. This is no longer the case. Swansea's economy is now post-industrial in terms of employment.

Housing

3.6 By 1960 the intervention of the local state in the housing market, through the building of council estates on the periphery of the then built-up area, combined with slum clearance, had, since World War I, resulted in a vast improvement in the total housing stock. This improvement combined with rising wages made it possible for working class people to pay rents for decent council accommodation. As a result the occupants of council estates were spread over a wide range of strata within the working class. Nonetheless, in spite of these major differences, you would, if you were working class in the Swansea of both 1920 and 1960, almost certainly have rented your living accommodation.

3.7 In 2002 70% of the population owned their own homes and council tenancies have become increasingly concentrated among the most vulnerable members of society. Council houses are being pulled down (not put up) or sold off to Housing Associations (South Wales Evening Post: 28/10/03) and existing centrally-located properties are being bought up and renovated by housing societies; indeed the disposal of the entire council housing stock is now (February 2005) being considered.

3.8 In 1960 the Council had a waiting list for housing of 6000, and 14 percent of all adults were either sharing a dwelling with another household or living in a household that included another couple. In 1960, as in 1900, there was still a shortage of affordable working class housing of a quality acceptable by the standards of the day, though the shortage had greatly diminished and the standards greatly improved (Rosser and Harris, 1965:62).

3.9 By 2002 only 1.2 percent of the adult population was living in shared accommodation (some of these are accounted for by minority ethnic families who choose to live together in this way) and the number on the housing list had fallen to 2000. Most of those on the housing list were people who were not in urgent need of housing in the 1960s sense but people who wanted or needed to transfer to other locations, usually so that they could live nearer to relatives (Swansea Housing Department: private communication, 2002). In the present, the factor most likely to cause families to double up is the inability of couples to find the deposit on a starter home due to the recent boom in housing prices that affected Swansea in 2003-4. According to the Halifax Building Society, in the twelve months ending September 2003, Swansea experienced the fourth largest price rise of any city in the UK. The average house price in Swansea was then £113,000 compared with the Welsh average of £101,000 and the UK average of £134,000 (South Wales Evening Post 2002, 13/10/03). The exceptional recent rise in house prices is partly due to the development of Swansea into a resort, associated with the past development of derelict docks as a marina, and the development of another set of docks with stunning views of Swansea Bay as an area of up-market housing which is attracting up-market in-migration and increasing the value of surrounding properties.

Theorising social change

3.10 That social change in the period after 1960 is qualitatively different from social change in the preceding sixty years is attested to by the attempts made to invent names for the type of society that has come into existence during recent decades. Such attempts often involve grand categories which are used to classify whole societies (e.g. 'modern'/'post modern') and no more suffice than does the resort to an examination of aspects of a society's life as represented by quantitative indicators (e.g. percentage employed in service industries). Whatever their merits they fail as means for apprehending the ways in which day-to-day life has changed and leave the sociologist struggling like Rosser and Harris's prime informant who was reduced to saying 'There's a different atmosphere now altogether!' (Rosser 1965, p.11). There's as much difference in 'atmosphere' between 1960 and 2002 as that reported between 1960 and 1910. In what follows we attempt to begin to capture that change in 'atmosphere'.

3.11 The most obvious change that has taken place between the date of the original study and the present enquiry is the decline in the notion of the public as an open arena (where one is observed by strangers and for which one prepares as for a performance on a stage) as opposed to the private arena of the family household where all those present are familiar (sic), pretence is pointless and behaviour varies according to the particular relationship between members of pairs of actors. This is exemplified by the common practice in the 1950s and 1960s of women donning hat and gloves as a sign of respectability when venturing into the public realm and is captured in the illustrations from reading schemes of the time. In contemporary culture this distinction is blurred and household and extra-household settings become equally contexts in which persons may pursue their individual ends with little reference to the responses of others.

3.12 One way of capturing the nature of those changes that are most relevant to family change is therefore to use the classic distinction between the collectivity and the individual. In the public domain there is not any necessarily recognised collectivity whose members have a shared consciousness comprising normative standards in terms of which public behaviour can be judged, neither is there any set of social categories to which specific normative expectations can apply. That is to say that the individual's identity is not ascribed by the collectivity, nor even chosen by the individual from a set of alternatives provided by the collectivity, but negotiated by the individual through a process of social interaction facilitated by the visible signs and markers constituted by their possessions. There are now few purely social identities that are stable and no master identities whose significance is so diffuse that they rival the past identities of occupation, class and culture.

3.13 Another way of putting this point is to say that there are no longer clearly defined social positions of wide social significance for persons to occupy to which clearly specified rights and duties attach. As a result, the idea of duty to any collectivity has evaporated and individual rights come to appear as the property of individuals, rights that exist independently of any social context. A corollary of the movement away from collectivism to individualism is that cooperation between individuals is increasingly achieved by means of exchange, rather than by the rules of organisations or the issuing of commands, so that people are more frequently linked by participation in markets than by relationships in or through institutions. This, as we shall see, has implications for differentiation within family and kinship networks.

3.14 All this is not to claim that social life in Swansea in the early twenty-first century is chaotic, random, dis-ordered. It is to claim that it has been subject to a process of de-institutionalisation, and is therefore increasingly societally unregulated. The most striking example of de-institutionalisation is the increasing replacement of the institution of marriage by cohabitation (entered into as a purely private arrangement) - though the proportion of the 2002 Swansea sample cohabiting is only 5%. The notion of de-institutionalisation is closely related to the Durkheimian notion of 'de-regulation' and Norbert Elias's notion of 'informalisation' (see Elias 1996:Chapter 1A). Elias's notion involves a movement between two different types of constraint on behaviour, namely from external, social restraints to internal, individual constraints. Elias is anxious to insist that this shift is a new phase in the 'civilising process', not its reverse. Elias would not want to claim therefore that de-institutionalisation (as a result of de-regulation and informalisation) involves the end of civilisation. However, de-institutionalisation has had the result that the new member of society no longer looks to the past for guidance, not merely because the speed of change means that the old rules about how things should be done no longer apply, but because, outside its bureaucracies, our society increasingly lacks rules about how things are to be done. As a result, instead of the past being privileged over the present, as in the traditional society of 1960's Swansea, the present is privileged over the past.

3.15 Characterised in this way, and contra Elias, the transition to the contemporary form of social consciousness may be seen as betokening the end of civilisation and, indeed, the end of society. There is a long sociological tradition, of which Parsons (for discussion see Harris, 1983: 57-9) is the most notable exemplar, of regarding the family as a point of articulation involving 'strain' and tension between past and future, tradition and modernity and having a structure which embodies values and orientations antipathetic to those integral to 'the [modern] wider society'. Similarly Beck (Beck, 1992: 114-5) postulates an opposition between market capitalism and the logic of family life such that 'the ultimate market society is a childless society'. It is possible to look to the family either as a bastion against egoistic individualism and total anomie or as a reactionary institution, the site of the final struggle between 'then' and 'now' resulting in its own destruction.

3.16 There is then an apparent contradiction between Swansea's experience of the immense economic and cultural changes which the UK has undergone in the last fifty years and the broad quantitative results of the1960 and the 2002 family surveys. Anyone who is familiar with the 1965 book and who reads the report of the preliminary results of the 2002 survey (Charles et al. 2003) will be struck by the extent to which family life in Swansea seems to have continued relatively unchanged. There are two reasons for this. The first is that the most striking changes concern the increasing number of people who have not yet, many of whom who will never, found residential groups comprising parents and children. There have been major changes in the pattern of family formation and family dissolution and re-formation but once formed (or re-formed) family life seems to follow the same sequences and maintain the same relationships with extra-familial kin in 2002 as in 1960. While there are many minor differences there is no major change. The reason for this is suggested in a recent paper (Ribbens McCarthy et al, 2000). In our terms, the paper shows how the egoism of the couple, whose members consider each other to be a condition of their self –development and who share the common goal of intimacy, cannot survive the arrival of children who, in their helplessness, treat the parents as means to the children's development and whose needs have to take primacy over those of the parents as individuals and as a couple. The arrival of children provides the basis for overcoming the alienation between the new parents and their own parents and between adult siblings. Whether that alienation derives from generational conflict or merely disparity between life-styles based on different individual choices, the arrival of children means that the parties now share a profound life situation – parenthood - which generates needs in the younger parent which the older parent may be able to supply. The cultural transformations of the last fifty years cannot of themselves alter these facts of life. They may, however, horribly exacerbate the tensions between individuals within family situations insofar as they have entailed the de-institutionalisation of family relationships; compared with 1960, relationships between partners and between parents and children have to be negotiated to an unprecedented degree because of the relative absence of normative rules and expectations.

Part Two: Demographic, industrial and occupational change

4.1 Having attempted a preliminary characterisation of the social change that has occurred in the last 40 years, we now turn our attention to specifying the structural changes which have taken place in Swansea between 1960 and 2002. We focus on three major structural changes, demographic, industrial and occupational; these have either produced, or themselves constitute, major changes in Swansea's social structure and they involve major changes in family life. Central to them are gender specific changes. First is the decline in female domesticity stressed by Rosser and Harris, which was well under way in 1960, and which they attributed primarily to demographic factors: principally the decline in female fertility in the first half of the twentieth century. Second is the decline in male labour market participation and the rise in female labour market participation. Both have to be understood with reference to both demand and supply factors. Demand side factors in the labour market are chiefly the changing industrial structure and supply side factors are domestic, namely domestic divisions of labour, number and ages of children, childcare arrangements etc. Greater female labour market participation may be viewed as both a cause and consequence of demographic changes in the second half of the century. It was also facilitated by the decline in female domesticity that had occurred in the first half of the century and which itself had been made possible by the concomitant improvement of living standards and housing and the introduction of affordable domestic technology.Demographic change

4.2 Between 1900 and 1950 there were enormous demographic changes (Rosser & Harris 1965:171-7) and some of these trends, chiefly the decline in fertility and increased longevity, have persisted throughout the last fifty years. What distinguishes the second from first the half of the twentieth century is that some of the changes that have occurred within it represent a reversal of patterns of change established in the first half.

4.3 The more recent changes are well known (see Anderson in Anderson 1996) and can be briefly summarised. The mean age at first marriage, which fell throughout the first half of the century, bottomed out in the early seventies and has been rising ever since, reaching 30.6 for males and 28.4 for women in mid 2001 (ONS, 2002: 85). The rate of marriage (loc.cit)) and the proportion over 16 married (ONS, 2001: 83-85) have been falling ever since. These statistics are the product of four factors. The first is the de-institutionalisation of reproductive partnerships - the increasing replacement of 'partnership by marriage' by 'partnership by cohabitation', the second is the practice of cohabitation before 'partnership by marriage' - these two factors resulting in the increased number of births outside marriage to nearly 40% by 2001 (ONS 2002: 6), and the third is the postponement of partnership which is reflected in the later age of 'partnership by marriage' (on the incidence of cohabitation see Haskey, 1999). The last factor is the increased incidence of lifelong 'singleness' and childlessness. As a consequence the proportion of the time potentially fertile women spend in a heterosexual partnership has been falling and as a result the fertility of women in such partnerships has fallen. Overall fertility had fallen to substantially below replacement level by the early seventies where it has remained ever since (ONS, 2002: Table 3.1)

4.4 These changes entail a decline in the rate of family formation and a decline in the proportion of the adult population who are in partnerships that have generated or can reasonably be expected to generate children. This represents the 'decline of the family' from an institution in which adult participation was the norm to one in which participation is regarded as a matter of personal choice that is no longer made by 'everyone' but is the choice of a small majority.

4.5 One of the reasons that not everyone makes the choice is because, through the mass media, statistical information is easily available which demonstrates that reproductive partnerships have a high rate of failure (divorce). High rates of divorce in any given generation have a knock-on effect in the following generation since its members have personal experience of divorce in their parents' generation which reinforces the impact of the statistics. High rates of family dissolution result in higher levels of lone-parent households the majority of which are temporary since divorcees show a high propensity to re-partner. Like the unemployed who, in full employment conditions, are 'between jobs', the majority of lone parents in lone-parent households may therefore be thought of as being between marriages or (if they were not married to the absent partner) between partnerships.

4.6 The last demographic factor subject to continuous change is mortality. Here the trends established in the period before 1960 have not been reversed: expectation of life for both sexes continues to increase and with it the number and proportion of the population formed by the statutory old and within that category the proportion formed by the old 'old'. Increases in longevity have implications for the sex ratio of the population since women are still more longevous than men and that means that the older the population the more marriages/partnerships are broken by the death of the man and hence the greater the number of single person households inhabited by bereft women.

4.7 All these demographic changes necessarily have effects on household composition producing an increase in the number of single person households comprising family remnants among the old and, earlier in the life course, family rejectors, a decline in the proportion of households with children under sixteen, a decline in the proportion of nuclear family households and a transformation of the reproductive cycle of the domestic group. This cycle now starts relatively very late, has a short nuclear phase, and is likely to have a longer than expected time in its dispersal phase due to late partnership of the adult children. The original partners will spend a longer time in a household by themselves and the survivor will spend a longer time as a widowed person living alone. The increasing number of those who do not partner and reproduce means that once their parental generation is dead they will have virtually no kin in the descendent generation with which their household can be linked. In contrast one of the effects of high rates of partnership dissolution and reconstitution is to multiply the number of ties between households.

Industrial change

4.8 There is one major continuity between the first and second halves of the twentieth century and that is that changes within workers' households of whatever kind have on the whole tended to facilitate labour market participation of the adults within them. Barriers to participation have been located in the market rather than the household whether, in the market, they have taken the form of glass ceilings for upwardly mobile women or of age discrimination against downwardly mobile redundant men. However, lowering barriers within the household will have no effect on members' labour market participation unless the market within which the household is located is able to supply employment opportunities.

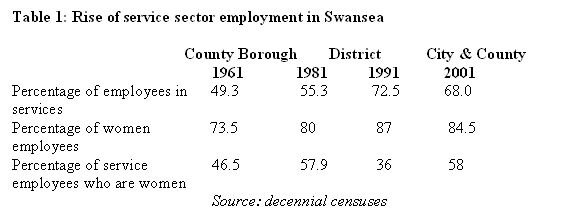

4.9 We have already briefly noted the transformation of the Swansea labour market from an industrial to a post-industrial one. This is reflected in the fact that between 1961 and 2001 there was a sharp decline in the proportion of the working population employed in manufacturing, construction, and transport and communication and a corresponding increase in those employed in the service industries in the 1980s. This increase in service sector employment is shown in Table 1.

|

As we can see, these changes are also associated with an increase in employment opportunities for women.

Labour Market Participation

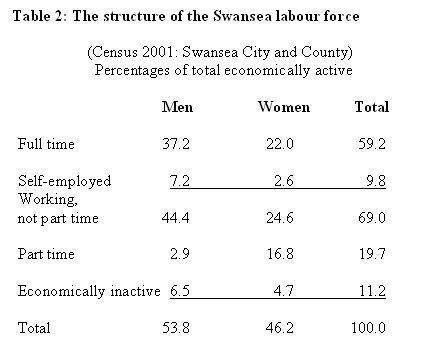

4.10 The existence of job opportunities in sectors of the economy likely to be attractive to women, such as those in the service sector, has had an effect on female economic activity rates. In Swansea in 1961 the activity rate for women was 29.4 compared with 87.7 for men. The equivalent figures for 2001 were 52.9 and 64.3. The changes represented by these figures are very striking. However they take no account of gender differences in participation in part-time employment which has risen for both women and men since 1961. Thus in 1961, 0.6% of economically active men were part-time compared with 18% of economically active women; in 2001, 5.5% of economically active men were part-time compared with 36% of economically active women. Table 2 shows the structure of the Swansea labour force in 2001 in order to take account of this.

|

4.11 Unsurprisingly the labour market is quite clearly male-dominated if non-part-time employment only is taken into account, with full time and self-employed men together constituting 44.4% of the labour force compared with a figure of 24.6% for women. Women however constitute a third of the non-part time sector in 2001 compared with 28% in 1961. As might be expected it is part-time work which pushes women's labour force participation up to near equality with that of men. It would of course be a mistake to suppose that the women recorded as part time are a breed apart who do special jobs called 'part-time jobs'. On the contrary, women's part-time status is highly family-phase sensitive and is the result of their negotiating between the demands of other household members and employers.

Occupational change and stratification

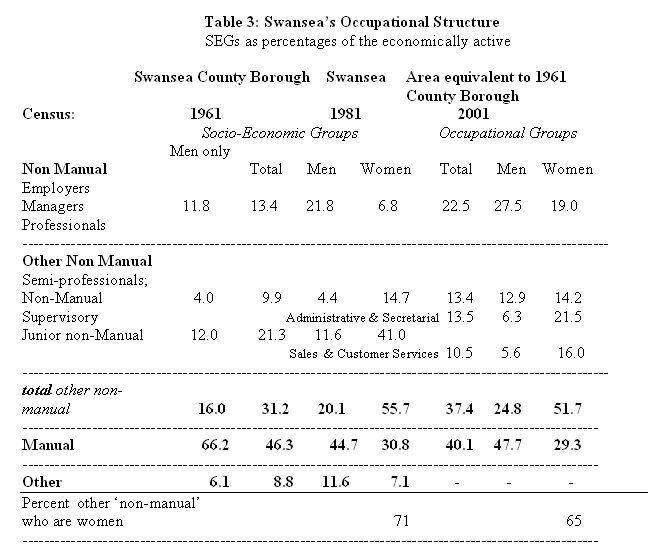

4.12 Because the period 1961-2001 has seen very considerable changes in occupational categories it is not possible to make exact comparisons between occupational distributions over different dates. Moreover Swansea has enlarged its boundaries twice since 1961: boundary changes in the seventies were minor: the inclusion of the erstwhile rural district of Gower, those in the nineties were, however, major - the inclusion of the neighbouring town of Pontardulais and its hinterland. Thus, for 2001 and for purposes of comparison, we have constituted an area equivalent to that of the 1961 borough and tabulated corresponding census data on a limited number of variables. In order to investigate the way the occupational structure had changed we used data classified in terms of the Registrar General's Socio-Economic Group for the 1961 to 1991 censuses and the ONS's occupational groups for 2001 (ONS 2001). SEG data were available only for men in 1961.

|

4.13 As we can see from Table 3, the proportion of economically active men in manual occupations has fallen since 1961 from two thirds to a little below half in 2001, the remaining men being distributed between managerial and 'other non-manual' occupations. In contrast, in spite of the near doubling of the female activity rate in the period, the proportion of economically active women in 'other non-manual' occupations has remained fairly steady at slightly above 50% for the last twenty years. The implication of this is that there has been an increase in the numbers of 'other non-manual' jobs which balances the increased supply of female labour concentrated in the 'other non-manual' sector. Only a quarter of men are in this sector of employment. Conversely less than one fifth of economically active women are in manual occupations. However, whereas in 1981 female representation in managerial occupations was only a third of men's, by 2001 it had increased to two thirds. Overall the 2001 distribution of economically active women is skewed upwards compared with 1981 in favour of the managerial occupations and to the slight disadvantage of both the 'other non-manual' and the manual group.

4.14 The shape of the occupational distribution taken as a whole has changed dramatically. The traditional distribution was shaped like a pyramid. It was composed of a small elite group at the top, a large mass of 'ordinary working people' at the bottom and a medium sized stratum composed of people who were 'in between'. The 2001 male occupational distribution echoes this: manual workers still constitute the largest group, though it is much shrunken, and the other two groups are enormously enlarged and are of equal size. What makes the overall 2001 distribution depart so dramatically from the traditional is the distribution of women. Nearly two thirds of women are 'in between' thereby creating a bulge in the middle of the occupational structure. Their distribution is therefore 'oval' as is the distribution of the whole work force when the distributions of the two sexes are added together.

4.15 The authors of the original study developed their occupational classification for the identification of 'social class'. Space forbids any discussion of either their concept of class or its operational definition and the attempt of the present authors to replicate it. This has been dealt with at length elsewhere (Davies and Charles, 2002; Harris, Charles and Davies, 2004). The most important difference between the 1960 occupational classification procedures and those of the re-study was that in 1960 the occupations ascribed to women respondents were those of their husbands while in 2002 married women's own occupations were coded. Since women are over-represented among 'other non-manual occupations' this shift in procedure naturally exaggerated the extent to which the occupational distribution of the sample has changed from a pyramid to an oval in the years between 1960 and 2002. However, whichever type of classification is used, and however women's occupations are recorded, the comparison of the results of the 1960 classifications with those of the 2002 study yield the same broad conclusions: a shift in the occupational structure from a pyramid to an oval and a much more even distribution of people between top, bottom and 'in between' than was the case in the past.

Part Three: Differentiation within the Family

5.1 Changes in the class structure were written small through three generations of the kin of Rosser and Harris's informants and by the 1960s had resulted in the members of potential extended family groups (henceforth PEFGs) being differentiated along class and occupational as well as cultural and residential lines. It was Rosser and Harris's contention that this differentiation hindered the formation of solidary extended kin groups (such as those recorded in Bethnal Green in 1954 and remembered in 1960 by the older generation of Swansea respondents) and had resulted in their replacement by what they termed, following Litwak (1960) 'modified extended families', groupings rather than groups, between whose members strong ties still existed. It is therefore appropriate to conclude this over-view of social change in relation to the family in Swansea with an examination of how differentiated Swansea's PEFGs have become.5.2 As regards residence there was little difference between the 1960 and 2002 samples in the proximity of the last seen child. However, the proximity of respondents to parents and siblings declined. The proportion with parents living within Swansea fell between the two surveys from just over 70 per cent to just over 60 per cent. The most marked change concerned siblings. The proportion with the last seen sibling living within Swansea fell from just over 70 per cent to just under 60 per cent. For all three categories of kin - parents, siblings and children - the proportion of 2002 respondents with the relative concerned living outside Britain was miniscule - under 5%. However, the proportion of respondents with the relative concerned living outside Wales in 2002 was marginally lower than the equivalent figures for 'outside Swansea' in 1960. These findings suggest a marked increase in the scale of the spatial distribution of close kin within Britain, remarkably little change in respect of parents and children but a significant increase in the degree of dispersion of siblings. The changes, in other words, have more consequences for the maintenance of the kinship system than for the formation of extended family groups whose adult core has always been two generational.

5.3 Because of the decline of Welsh-speaking in the first half of the 20th century, 54% of the 1960 sample neither spoke Welsh nor had parents who spoke Welsh. As a result, Welsh-speaking was not in 1960 a major differentiating factor between the generations, the members of only 22% of parent-child pairs differing as to whether or not they had any Welsh (Rosser & Harris 1965:120). The above figures refer to the whole of the 1960 sample and are therefore measures of linguistic change in the whole population, while we are concerned here with the differentiation of PEFGs and these comprise only living members. Because the 1960 figures included dead parents in their comparisons, they will, if used as an indicator of PEFG differentiation by language, exaggerate it and this should be borne in mind when considering the 2002 figures. The 2002 figures show only a small decline on the 1960 figures in the proportion of parents and children differing in terms of the ability to speak at least some Welsh (from 22% to 19%) which, given the exaggeration involved in the 1960 figures means that on the language dimension there has been very little increase in differentiation between the two dates. The significance, for the family, of the decline in Welsh during the first half of the twentieth century is that it represents the loss of a strong binding factor within the group; but in the second half of the century Welsh-speaking does not represent an important dimension of differentiation militating against group solidarity.

5.4 The changes in the occupational structure which have been described above involve a movement from an occupational class structure with one very big and two quite small classes to three substantial classes. Of necessity such a change must generate greater occupational inter-generational discrepancy between members of PEFGs. The occupational classification used by Rosser and Harris was three fold, involving a straight manual-non manual distinction but in addition distinguishing class IIIa (other non-manual) from classes I & II. Rosser and Harris called I& II 'managerial', IIIa 'clerical' and classes IIIb, IV & V 'artisanal' (1965, pp. 96-7). Using this classification to compare the occupations of the 2002 respondents with those of their living fathers (we are here using father's occupation for purposes of comparison with the original survey) we find that 65% were of a different occupational level from their fathers, 56% male and 70% female. For 34 % of the male respondents, but only 25% of the female respondents, the difference in 2002 was substantial in that one of the pair was managerial and the other artisanal. In the cases remaining, 22% of men and 45% of women, one of the pair was clerical; in other words there was no substantial parent-respondent difference.

5.5 There are no exactly corresponding figures from the 1960 survey. We have however 1960 figures for occupied male respondents and the occupations of all their fathers and not just living fathers (Rosser and Harris 1965: 96). If we define occupational similarity in the same way for the 1960 data we find that only 31% of the 1960 male respondents were in different occupational classes from their fathers and 69% were at the same occupational level. This compares with 2002 when 56% of the male respondents were of a different occupational level and only 44% had the same occupational level as their fathers. Because the 1960 figure includes subjects with dead fathers, this serves to exaggerate inter-generational differences when comparisons are made with the 2002 data. When one considers the changes in the occupational structure that have been described above however these findings are less surprising than might at first appear. Those changes involve a movement from an occupational class structure with one very big and two quite small classes to three substantial classes, such a change must of necessity generate greater occupational inter-generational discrepancy between members of PEFGs.

5.6 Because of the low levels of participation of women in the 1960s labour market and their inferior position within it, Rosser and Harris did not compare the occupational status of husbands and wives. However, because of the increases in women's employment between the two surveys and as an experiment, we created a new variable which concerned heterosexual couples rather than individuals and classified them according to the pattern of economic activity of the partners and their relative occupational statuses. Fifty eight percent of the total sample were members of heterosexual couples. Over a third of these were couples in which both partners were economically active either part or full time; a further fifth had only one partner working. Where both partners were working, the majority (57%) worked full time. The only other major category (39%) was that comprising couples where the male worked full time and the woman worked part time.

5.7 Each partner was classified as managerial, clerical or artisanal and couples were classified according to whether, in these terms, partners had equal status or differed by one or two classes. Of couples with both partners working, 60% had partners of different occupational statuses. This figure may be compared with the figure of 65% cited above for different statuses between respondent and living fathers in the 2002 sample and with a figure of 31% in the 1960 sample for different statuses between male respondents and all fathers. In other words there is more occupational difference between heterosexual partners in Swansea in 2002 (60%) than between fathers and sons in Swansea in1960 (31%). Moreover among those couples where partners did not have the same occupational status (and the couple could not therefore be assigned an unambiguous occupational status), the woman had the higher status in 60% of the cases.

5.8 If we consider now only those couples where the woman has the higher status we find that in 57% of these couples the woman was in an 'other non-manual' occupation and the man was in a 'manual' occupation. These cases were typically women working in secretarial or clerical jobs with partners who were in skilled manual work and as such do not represent any transgression of 'traditional' gender divisions. More interesting are those among the 43% of 'woman higher status' couples that do not comprise an 'other non-manual' woman and a 'manual' man. Of these 43 percentage points, 33 are accounted for by the partnering of managerial women with artisanal men and only 10 points by the partnering of managerial women with clerical men. These findings suggest that the trend towards increasing differentiation within extended family networks identified by Rosser and Harris has continued and is now to be found within the reproductive partnership at the heart of the elementary family as well as in the wider kinship network.

5.9 As might be expected economic activity varied significantly over the family cycle for both sexes, activity for both being highest when all children were living at home and men's activity rates being consistently higher than those for women but not by a great amount. Part time work, which is four times as common among women as among men, was also most frequently found among women when children were living at home.

5.10 Now it is tempting to suppose that the determinant of men's economic status is their position in the labour market and that the determinant of women's position is their involvement in reproduction: those women not working full time are working part-time because of child care and those men not working full time are unemployed because of their position in the labour market. Obviously there is some truth in this. But such explanations ignore the fact that most of the actors whose labour market status the statistics record are members of couples and are subject to the opportunities and constraints posed both by the position of the couple in the reproductive process and by their relative positions in the labour market.

5.11 In contemporary economic conditions both partners are actually or potentially economically active as well as potentially or actually parents. For the majority of couples, full-time economic activity by both partners throughout the whole period of child-bearing and rearing is not possible. This means that partners are faced with a bewildering number of choices not all of which turn out to be actualisable since they are conditioned by a changing labour market and the way the reproductive cards fall. The 'freedom' implied by the word 'choice' turns out not to entail greater control over one's life circumstances because in a society with a swiftly changing and highly diversified structure and culture one's future circumstances turn out to be increasingly unpredictable either by the individual or 'society'. The questioning of a normative script for couples ('marriage') and the lack of any stable empirical expectations of what in fact any given partnership is going to involve mean that potential partners are unwilling to enter into any sort of contract. In other words the high risks attached to any long-term relationship results in the de-institutionalisation of partnership. As a result the terms of the relationship are up for continual renegotiation. This increases the chance of partnership failure. These negotiations necessarily concern the part that each partner plays in the labour market and in the work involved in social reproduction (child rearing) but are conditioned by the position of the partners in the rapidly changing local labour market and in turn condition their labour market behaviour. There is therefore a dialectic going on between productive and reproductive labour, the market calling forth partners through the supply of, for example, jobs attractive to women which in turn prompts a renegotiation of the division of household labour in all its forms…. And so on. The partnership relation is the social medium through which the dialectic between productive and reproductive labour is worked out.

5.12 The nature of the social change that has taken place between the two surveys has resulted in a shift in the focus of the research problem. The original study was concerned to investigate the extent of differentiation within extended family networks and the problems that this created in terms of providing support and a sense of belonging to family members. During the course of the current study it has become clear that the 21st century presents us with a new problematic. This problematic concerns the way differentiation in the wider society affects not merely extended family groups but penetrates to the heart of the elementary family itself – the reproductive couple.

Notes

1A note on the problem of typicality. The 2002 study was designed to provide a comparison with a previous study of the same place (Swansea, South West Wales), at a different time:1960. The study generating the 1960 data was undertaken to test the conclusions of a slightly earlier study (data 1953-5) in a different place: the London suburb of Bethnal Green (Young and Willmott, 1957, p.14). Nobody at that time questioned the typicality of the Bethnal Green study which was a study of the population of an allegedly working class community. However questions were raised about the typicality of the 1960s Swansea study. Its findings were deemed irrelevant to England because Wales was still in the early stages of the modernisation process which, through the twin mechanisms of 'urbanisation' and 'industrialisation', was widely believed to have led to the shrinkage of the elementary family to its 'nuclear core'.The statistical material we present in this paper concerning Swansea's industrial, occupational and class structure should be useful both for comparative purposes and to enable readers to contextualise the family data presented and our arguments concerning them. On the basis of this evidence readers may wish to argue, using whatever criteria they choose, that the conclusions presented are typical or a-typical of whatever population they select.

However, there is one social dimension which is directly relevant to the question of the 'typicality' of our findings regarding the closeness of family ties and that is whether or not the Swansea population is self-selected for 'closeness'. In the case of both Bethnal Green in 1954 and Swansea in 1960 it could be argued that movement out of the survey area had resulted in the loss of people with loose kinship ties: in Swansea during the thirties depression when people left in search of work and in Bethnal Green after WWII when people left for the new council estate ('Greenleigh') in Dagenham. The departure of people with loose family connections would have left a population with strong family ties. However between 1960 and 2002 Swansea experienced no substantial net population loss and indeed kin locations recorded in the 2002 survey show some movement into Swansea from areas immediately adjacent to it; this reduces the possibility that our findings are peculiar to Swansea because of any atypical migration history.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based was funded by the ESRC (R000238454) and is part of the project 'Social change, family formation and kin relationships.

References

ANDERSON, M. (ed.) (1996) British Population History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

ANDERSON, M. (1996) 'Population Change: Trends and Patterns and Movement' in Anderson, M. (ed.) British Population History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

ATKINSON, A.B. (2000) 'Distribution of Income and Wealth' in Halsey and Webb.

BECK, U. (1992) Risk Society. London: Sage

BOTT, E (1957) Family and Social Network. London: Tavistock.

CHARLES, N., C. Davies and C C Harris (2003)'Family Formation and Kin Relationships: 40 years of Social Change' Paper presented at the BSA conference at York. http://www.swan.ac.uk/sssid/Research/Res%20-%20Sociology.htm (Rosser and Harris re-study working papers, BSA 2003 survey paper)

DAVIES C A and Charles N (2002) 'The Piano in the Parlour: Methodological Issues in the Conduct of a Restudy', in Sociological Research Online, 7(2), http://www.socresonline.org.uk/7/2/davies.html

ELIAS, N. (1996) The Germans, Polity Press, being the English edition of Studien uber die Deutschen. Suhrkamp Verlag, 1989.

GALLIE, D. (2000) 'The Labour Force' in Halsey and Webb.

GRUNDY, E., Murphy M. and Shelton, N. (1999) 'Looking beyond the Household', Population Trends 97:19-27

HALSEY, A.H.and Webb, J. (2000) Twentieth Century British Social Trends. Basingstoke: Macmillan

HARRIS, C.C. (1983) Family and Industrial Society. London: Allen and Unwin

HARRIS, C.C., Charles, N. and Davies, C.A. (2004) Some Problems in the Comparative Use of 'Class' as a Descriptive Variable at Two Different Points in Time, http://www.swan.ac.uk/sssid/Research/Res%20-%20Sociology.htm (Rosser and Harris re-study working papers, Class paper 2004)

HARRIS, C.C, et al (1987) Redundancy and Recession. Oxford: Blackwell

HASKEY, J. (1999) 'Cohabitational and Marital Histories of Adults in Great Britain' Population Trends 96, Summer,1999: 13-24

LITWAK, E. (1960) 'Occupational mobility and extended family cohesion.' American Sociological Review 25, no 1, pp. 9-21.

LITWAK, E. 'Geographic mobility and extended family cohesion.' American Sociological Review 25, no 3, pp. 385-394.

ONS (2002) Population Trends, 103, Summer

ONS (2001) Population Trends, 103, Spring

RIBBENS MCCARTHY, J., Edwards, R. and Gillies, V (2000) 'Moral Tales of the Child and the Adult'. Sociology 34:785-803

ROSSER, C. and Harris, C.C. (1965) The Family and Social Change. London: Routledge

SOUTH WALES EVENING POST, 13/10/03, 'House prices still on the up', p.15.

SOUTH WALES EVENING POST, 28/10/03, 'Campaigners out to stop council homes sell off', p. 22.

YOUNG, M, and Willmott, P (1957) Family and Kinship in East London. London: Routledge