Deidre Wicks,

Gita Mishra and Lisa Milne (2002) 'Young Women, Work

and Inequality: Is It What They Want or What They Get? An

Australian contribution to research on women and workforce

participation'

Sociological Research

Online, vol. 7, no. 3,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/7/3/wicks.html>

To cite articles published in Sociological Research Online, please reference the above information and include paragraph numbers if necessary

Received: 27/9/2002 Accepted: 26/9/2002 Published: 22/10/2002

Abstract

Abstract Introduction

Introduction Method and Analysis

Method and Analysis

Results: The Quantitative Study 1996

(S1)

Results: The Quantitative Study 1996

(S1)

Click here for Table 2

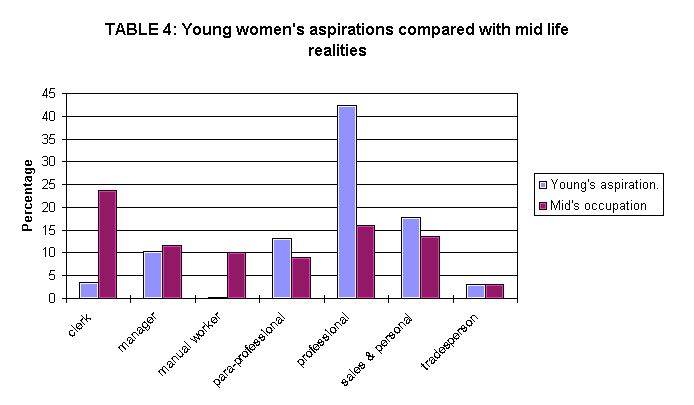

Table 4

Table 4 Disaggregated Results

Disaggregated Results

The Qualitative Study 2000 (S2)

The Qualitative Study 2000 (S2)

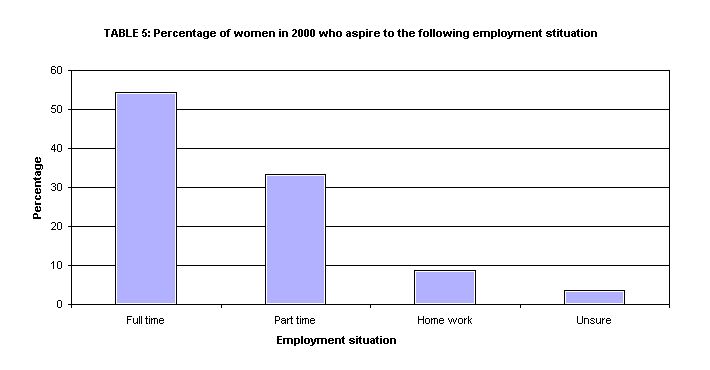

Table 5

Table 5I think you are what you do these days where your work is a big part of yourself... so, because it takes up so much of your time, it's really important to do something you enjoy and something that is a career as opposed to just a place you go every day to earn money.

What appeals to me about full time work is being able to do something I enjoy for a large period of my time. If you enjoy your job then you'd like to be doing it all the time. There is also the issue of financial stability, which is kind of necessary!

I just generally really like work... I really enjoy work and the stimulation and the work environment. I've actually done quite a lot of part time work in the past and I've found that full time work is a lot more rewarding and you can keep on top of things a lot better.

I'm the sort of person...well, I guess I'm career oriented and want to do well and... there's probably this perception that you need to be in full-time work to really get into it and get somewhere.

I guess it's not so much the full time paid work ... it's more the career that is important and with what I am going to do (television production) I assume that I'll be in full time work if I'm going where I want to be going in my career.

I don't think you can really have the same sort of career aspirations through part time work. It seems like most employers regard part time employees as only half committed and that they (the employees) are just there for the money rather than that they are actually dedicated to the job.

I'd prefer to be married with children.... I just think it's a more stable sort of situation for children. It's better if you can have two influences on your child and preferably the influences that created the child in the first place would be good. That would be the best situation I think you could choose for your child.

We're living together at the moment and we've got ourselves set up... with dogs and all that sort of stuff so.... If I'm going to have kids I want to be married before I have kids. (Interviewer: Why do you feel it's important to be married before you have kids) I think it's just the way I've been brought up.

Well... I mean I primarily want to be married because I want to have children and I feel that it's probably best to have two stable parents... Yeah I wouldn't want to get married for my own security... it'd matter more if I were to have children I think it would be in their better interests to have a more stable sort of home.

Being married...I guess having someone there to support you as well...and be there with you. You're not on your own.

Just sort of having a partner that you can share your life experiences with...you know...sort of having a like really close friend almost.

Probably companionship. It's just nice to think that you hopefully have married someone that you want to spend the rest of your life with.

Click here for Table 9

Social Class and Aspirations

Social Class and Aspirations

I'd like to win lotto and not work at all (laughs) but part time would be pretty ideal.

I'm hoping to have kids so I don't think I cannot work at all ... I just hate working five days and travelling. I know we have to do it (work) but I just think there is more to life. I'd like to have kids but not like to work full time I mean I'd like not to work at all but I think just our circumstances wouldn't allow us to have just one person working.

To be honest with you, I don't really have ambitions to be a businesswoman ... before I had but now since I got my job, it's too hard.... You don't have any time for a social life ....you just have to work and I think... what's your life for if you're just going to work and work. You have to enjoy life as well and I'm planning to have kids so I don't want to be like full time working. I want time for the children and for myself.

I get very stressed under too much responsibility so my career change would be something where I feel I don't feel I have so much responsibility to people that I seem to have in a teaching career.

I guess I'm looking for something that's a little less stressful ... and also, I'll probably look for a job that I don't have to come home from work and constantly be thinking of work all the time which is what I feel like I'm doing. You know, I come home and I've got work to do and it's a never ending cycle and I feel like I'm chasing my tail all the time and never getting to where I need to be... but I guess I'm a bit disillusioned in jobs and prospects and career at the moment and so that's sort of where I'm looking at now ... maybe that's why I'm turning to home and gardening and maybe even looking at children kind of thing.

Content Analysis

Content Analysis

I just think it's sort of a natural progression, you know, to use your experience and also to bring about some of your own ideas and vision about how things could operate I think you can do that better from a management position (obviously).

I guess I don't see what marriage gives you that you don't have in a relationship and I suppose I have a lot of negative connotations with the whole idea of marriage. It just seems like ... I mean it's a social construct but it's not one that I feel any particular affinity for. I don't necessarily think that having it sort of formalised in a marriage context is necessarily important or is necessarily something that I want in my relationship

Discussion

Discussion

Conclusion

Conclusion

Notes

Notes

Appendices

Appendices

AUSTRALIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS (1991) Census of Population and Housing. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

AUSTRALIAN BUREAU of STATISTICS (2000-2001). Labour Force Survey. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

ANDRES, L., ANISEF, P., KRAHN H., LOOKER, D. and THIESSEN, V. (1999) 'The Persistence of Social Structure: Cohort, Class and Gender Effects on the Occupational Aspirations and Expectations of Canadian Youth'. Journal of Youth Studies 2, 3, pp. 261-282.

BAXTER, J. and GIBSON, D. (1990). Double Take, AGPS, Canberra.

BECKER, G.S. (1985) 'Human capital, effort and the sexual division of labour'. Journal of Labour Economics 3, pp. 533-538.

BOURDIEU, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BRUEGEL, I. (1996) 'Whose Myths are They Anyway? A comment'. British Journal of Sociology 47,1, pp.175-177.

BURRIS, B. (1991) 'Employed Mothers: The Impact of Class and Marital Status on the Prioritizing of Family and Work'. Social Science Quarterly 72,1:50-66.

CONNELL, R.W. (1983) Which Way is Up? Essays on Sex, Class and Culture. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

CONNELL, R. W. (1987) Gender and Power. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

CROMPTON, R. and HARRIS, F. (1998). 'Gender Relations and Employment: The Impact of Occupation'. Work, Employment and Society 12, 2, pp 297-315.

EDWARDS, A. and MAGEREY, S. (editors) (1995). Women in a Restructuring Australia: Work and Welfare. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

GALLIE, D. (editor) (1988) Employment in Britain. Oxford: Blackwell.

GOLDTHORPE, J. H. (1980) Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

GREGORY, R. and HUNTER, B. (1995). The Macro Economy and the Growth of Ghettos and Urban Poverty in Australia. Centre for Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University, Discussion Paper 325, April, pp. 1-35.

HAKIM, C. (1991). 'Grateful Slaves and Self-Made Women: Fact and Fantasy in Women's Work Orientations'. European Sociological Review 7, pp.101- 21.

HAKIM, C. (1993). 'The Myth of Rising Female Employment'. Work, Employment and society 7, pp. 97-120.

HAKIM, C. (1995). 'Five Feminist Myths about Women's Employment'. British journal of Sociology 46, pp. 429-55.

HAKIM, C. (1996). 'The Sexual Division of Labour and Women's Heterogeneity'. British Journal of Sociology 47, pp. 178-88.

HAKIM, C. (2000) Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century. Preference Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

JACOBS, S. (1999). 'Trends in Women's Career Patterns and in Gender Occupational Mobility in Britain'. Gender, Work and Organization 6, 1, pp. 32- 46.

LOOKER, E. and MAGEE, P. (2000) 'Gender and Work: The Occupational Expectations of Young Women and Men in the 1990's'. Gender Issues 18, 2, pp. 74-88.

LUKES, S, 1974. Power: A Radical View. London: Macmillan.

POOLE, M., LANGAN-FOX. and OMODEI, M. (1990). 'Determining Career Orientations in Women from Different Social-Class Backgrounds'. Sex Roles 23,9/10, pp. 471-490.

PROBERT, B. (1994). 'Women's working lives'. In PRITCHARD HUGHES, K. (editor) Contemporary Australian Feminism, Melbourne: Longman.

PROCTOR, L. and PADFIELD, M. (1999) 'Work Orientations and Women's Work: A Critique of Hakim's Theory of the Heterogeneity of Women'. Gender, Work and Organizations 6, pp.152-62.

REES, T. (1992). Women and the Labour Market. London: Routledge.

RUBERY, J., FAGAN, C., HORRELL, S. and BURCHELL, B. (1994) 'Part-time Work and Gender Inequality in the Labour Market'. In A. M. Scott (editor) Gender Segregation and Social Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 205- 34.

TAK WING CHAN (1999) 'Revolving Doors Re-examined: Occupational Sex Segregation Over The Life Course'. American Sociological Review 64, pp. 86-96.

WALSH, J. (1999). 'Myths and Counter-Myths: An Analysis of Part-Time Female Employees and Their Orientations to Work and Working Hours'. Work, Employment and Society 13, pp.179-203.

WICKS, D. and MISHRA, G. (1998) 'Young Australian Women and their Aspirations for Work, Education and Relationships'. In CARSON, E., JAMROZIC A. and WINEFIELD T. (editors) Unemployment: Economic Promise and Political Will. Brisbane: Australian Academic Press, pp. .89-100.