Marion Gibbon

(2000)

'The Health Analysis and Action Cycle an Empowering Approach to

Women's

Health'

Sociological Research Online, vol. 4,

no.

4, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/4/4/gibbon.html>

To cite articles published in Sociological Research Online, please reference the above information and include paragraph numbers if necessary

Received: 12/10/1999 Accepted: 28/2/2000 Published: 29/2/2000

Abstract

Abstract Introduction

Introduction Background

Background

Power

Power

Recognition of further differentiation and complexity according to each individual's experience of oppression. This has entailed awareness of the diversities between people in the same oppressed group, recognition that 'none of us belongs to one social compartment' and that attempts to reduce the complexities of people's experience to neat little boxes ... result in simplistic responses (Bray and Preston-Shoot, 1995: 47).

Different Forms

of

Power

Different Forms

of

Power

The multi-dimensional nature of power suggests that empowerment strategies for women must build on 'the power within' as a necessary adjunct to improving their ability to control resources, to determine agendas and make decisions.

Dimensions

of

Empowerment

Dimensions

of

Empowerment

Figure 1: Forms of empowerment

Figure 2: Empowering networks

The process by which people, organisations or groups who are powerless a) become aware of the power dynamics at work in their life context, b) develop the skills and capacity for gaining some reasonable control over their lives and c) exercise this control without infringing on the rights of others and d) support the empowerment of others in the community (McWhirter, 1991).

The researcher should never ignore the obligation to those who give information and advice or who allow her into their own domain to watch the way they live their lives. The reciprocity implicit in this trust constitutes an obligation to be honoured by a sharing of knowledge and a promotion of understanding of the participants' actions and interests. It is good practice to seek out all sides of a conflict, so that, when the researcher becomes (inevitably) an advocate the advocacy will be more balanced and point in some way to just solutions.

If we accept that conducting and participating in research is an interactive process, what participants get or take from it should concern us. Whilst we are not claiming that researchers have the 'power' to change individuals' attitudes, behaviour and perceptions, we do have the power to construct research which involves questioning dominant/oppressive discourses; this can occur within the process of 'doing' research, and need not be limited to the analysis and writing-up stages.

In the radical value base it involves working alongside oppressed people to challenge the source of their oppression in the abuse of power by others. Borrowed by the traditional value base it is used to describe a process of enabling people to acquire the skills and self-confidence needed to bring improvements in the quality of their lives, or helping people to compete more effectively for scare resources.

Factors that Contribute

to

and Hinder Empowerment

Factors that Contribute

to

and Hinder Empowerment

Figure 3: The Women's Empowerment Model

Collective or

Group

Empowerment

Collective or

Group

Empowerment

Contributing

Factors

Contributing

Factors

Hindering

Factors

Hindering

Factors

Individual or

Personal

Empowerment

Individual or

Personal

Empowerment

MYSELF: What kinds of changes have you seen in the individual women?CO-WORKER: They were shy to speak but these days the women who did not speak have more confidence. Their capacity to speak has increase they have more speaking power. Now they can speak freely. They can speak in front of others not only you and me but with outsiders too. The other day there were visitors from Kathmandu and they freely answered their questions and also made questions to them.

MYSELF: How do you think the group decision-making skills have changed?

CO-WORKER: Before any decision was made individually. When starting now they meet in a group and make decisions together when they do the meeting. I saw the minutes and I saw they say now their decisions are made and recorded. They are now minuting and recording their decisions. They are deciding many things in a group (Interview with co-worker September 1998).

MYSELF: Have you seen any changes in the status of the women who have been involved in groups?CO-WORKER: How can I say? Exactly I cannot say. I can say they now feel confident that they can also do something for the community. It does not mean they always have to depend on others. There are now more empowered. These days they are able to discuss more with their husbands. (Interview with co-worker September 1998).

Contributing

Factors

Contributing

Factors

Hindering

Factors

Hindering

Factors

| Contributing factors | Hindering factors |

Positive social identity within

a

group

|

Negative social identity within a

group

|

Individual beneficial

factors

|

Individual hindering factors

|

The Health Analysis

and

Action Cycle as an Empowering Approach

The Health Analysis

and

Action Cycle as an Empowering Approach

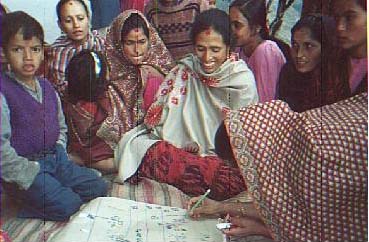

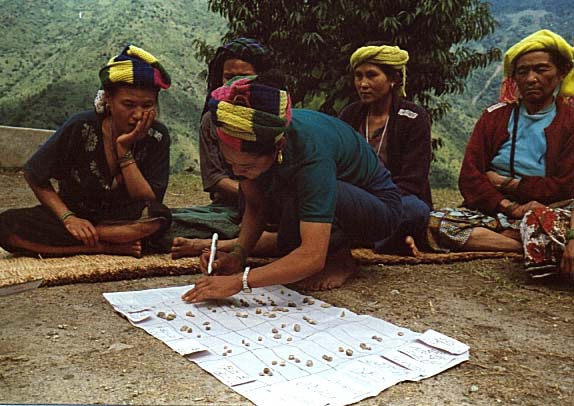

Photograph 1: The women's group makes their own community health map

Photograph 2: The women's group makes their own health matrix

The HAAC in

Action

The HAAC in

Action

Case study 1In Dhankuta two women's groups have made their own action plans and have joined forces to run a community health initiative. The groups identified that many families did not know how to make oral rehydration solution (ORS). They decided to organise a programme before the onset of the diarrhoea season. They obtained oral rehydration solution packets and set about teaching the women in their communities how to make packet ORS, to use rice water and other locally available solutions as ORS and, to administer ORS to someone with diarrhoea. They also decided that two of the members would stock ORS packets and they advertised this to everyone in the community. In this way the ORS packets would be readily available when required. The promotion of nun-chini-pani (sugar-salt solution) was not encouraged after discussions with UNICEF suggested that their research had found it to be more harmful than beneficial within the Rai community as many of them did not use sugar and it was therefore not easily available to them.

|

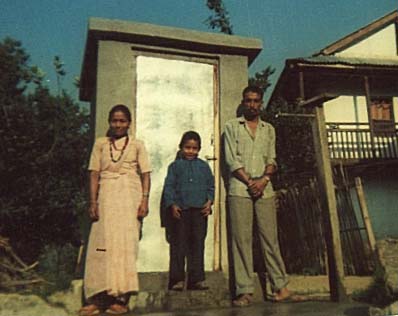

Case study 2Nineteen households now have latrines as a result of the HAAC process in Pangsing, Dhankuta district. There are differences in the latrines built as the photographs show (See Photograph 3 and Photograph 4). Socio-economic circumstances influence the outcomes of the approach. The Chhetri household is a wealthy one. They could raise the 3,000 Nepalese rupees required by the municipality as evidence to their commitment to building a latrine. The municipality then provided a further 12,000 Nepalese rupees to enable the family to build a permanent latrine. On the other hand the Rai family are economically deprived. To have three thousand Nepalese rupees is beyond their wildest dreams. However, they still endeavoured to build a latrine using the materials they had available to them. The latrine does at least have a concrete slab obtained by a donation from the community.

|

Photograph 3: The Chhetri latrine

Photograph 4: The Rai latrine

Case study 3Two literacy circles were formed after the HAAC workshops were completed. One group was predominantly Chhetri and the other group was mainly Rai. The Rai group completed six months of classes that were run daily from six o'clock to eight o'clock. The women were all assiduous in their attendance and enjoyed the classes. The Chhetri group completed four months of classes. The women were far more erratic in their attendance. They stopped the classes when their daily workloads started to increase due to the agricultural season.The Chhetri women although more economically advantaged had far less support from their families. The allocation of household tasks is biased against them. They have very little help from their husbands in tasks that are regarded as women's work.

|

Non-Governmental Organisation participant: Do your husbands help in your housework when you are out? Kamala Ghimre: This is the first time in my life that I have got the chance to say something in front of a large audience. So, I may make a mistake and I hope you do not mind. Yes, it is true that the PRA concept has changed our village. Our men used to scold us when we wanted to take part in meetings and many other useful programmes. They had the belief that women are only made for cooking and doing housework but nothing more. But nowadays we get the chance to participate in village meetings, development programmes and much more. But, still men do not help us in the work that they feel is only made for women. Such as when we come out to participate in programmes like this we have to go back and feed our children, cook rice, feed our animals and do all the work which we have been doing over the years.

Social Network

Analysis

Social Network

Analysis

Figure 4: Map to show Khalde women's social networks

Figure 5: Social networks of WEST's women's groups

Before no one ever heard us, now we get together and discuss our plans, talk to the ward chairman and our community is changing, we now have a voice (Community member, September 1998).

Things have changed in our community, before we had no latrines and our environment was dirty, now we can cut our fodder close to our houses as people now use latrines (Community member, September 1998).

Linking together development and women's situation, empowerment, and health; placing them in a context that includes historical, political, economic, cultural, social and local circumstances; and adopting a non-reductionist, non-linear, dialectical approach to understanding complex issues, provides a framework to reorient our thinking about health from pathogenic to salutogenic (Stein, 1997: 255-256).

Conclusion

Conclusion

Appendix: The Health Analysis and

Action Cycle as a Process Leading to Action

Appendix: The Health Analysis and

Action Cycle as a Process Leading to ActionIt is the second of these approaches that CHDP takes, using a broader, 'holistic' perspective on health and concerned with people's empowerment. Tones and Tilford (1994) use a model known as the health action model to explain this further. Efficient decision making requires conscious calculations of the costs and benefits of actions. Decisions are influenced by beliefs, motives and social pressures, which enable action to occur if and when the appropriate circumstances arise. The Health Analysis and Action Cycle aims to enhance efficient decision making and conscious analysis.

If the approach we are investigating is to be an empowering approach the provision of support to facilitate genuine decision making is a necessary component. It is therefore essential to take into account the constraints and facilitating factors interposed between intention and action. The facilitating factors are a necessary prerequisite for effective health promotion.

All the Health Analysis and Action Cycle steps allows the groups to discuss and visualise several aspects of health:

The input of external knowledge is limited as much as possible (although not entirely excluded) and the emphasis is put upon facilitating the discussion and the exchange of knowledge between the participants. The external knowledge that is introduced is discussed and not imposed on the group members and allows them to make decisions about incorporating it into their worldview. The closeness to the problem created by the use of participatory tools seems to increase the participants' ownership of the action to be taken. In the piloting phase we observed that most of the time the decisions taken by the groups were followed by actions.

As health is being considered in a 'holistic' way there are many influencing factors that need to be considered. The focus will be on health preventive measures that the participants can realise themselves as well as on action that needs to be taken to address health problems once they have occurred.

This section will illustrate the use several tools that come from participatory rural appraisal. The tools include health mapping, seasonal calendar, body map, and cause tree. Some of the health problems mentioned by the groups are seasonal. For this reason we decided to include a seasonal calendar to consider seasonal illnesses, in relation to seasonal attributes and to examine if any of the causes defined in the discussion around the health map have a seasonal dimension.

The following steps were used with seven groups of women. Of these the findings of six were analysed in depth. Each group had a maximum of twenty (more usually between ten and fifteen) as more than this meant everyone was not able to contribute and participate in a meaningful way. The steps were facilitated by someone outside the group.

Note: The dotted line shows how in the second cycle it is not necessary to re-list and identify problems.

Figure 1: The Health Analysis and Action Cycle

PRA is not a methodology but a framework that links a family of approaches that were developed to enable local people to obtain, share and analyse their knowledge of life and conditions. From this information they can then plan and act according to that knowledge. PRA flows from and in fact owes a lot to RRA (White, 1994) which was developed from participatory research (Freire, 1972). Where PRA needs to develop is to aggregate local knowledge to influence policy, to take local knowledge and apply it to decision making at a central level.

White and Taket (1997) outline the principles of PRA as the following:

PRA has been criticised, as it does not go beyond appraisal, and is therefore hailed not to incorporate analysis, planning, prioritisation of possible solutions, and finally a commitment to act. It may be a good set of tools for data collection but it does not explore the issues and assess different options and choices for action. It simplifies and overlooks the inherent problems in developing a plan of action. What do you do when there are conflicts of opinions, or different parties pursuing their own interests? It is apparent that there is a need for a further step. Participatory Appraisal of Needs and Development of Action (PANDA) takes on these tensions by incorporating tools from management sciences and operational research. PANDA sometimes but not imperatively uses a set of planning tools that was developed in the 1970s called the 'strategic choice approach' which incorporates ideas on participative decision making (White, 1994). These methods have been seen to be useful in Belize where the participatory and transparent nature of the techniques and the process facilitated learning.

The project aimed at helping the participants to visualise and structure the issues in terms of how they saw then, and ensuring that their main concerns were being aired. During the project, the incorporation of participative aids for decision-making helped the participants to consolidate what they learnt about their problems with what feasible options they could explore (White, 1994: 461).Participatory Learning and Action is a further development that has incurred to incorporate the idea that action is inherently important and that the approach goes beyond being a method of appraisal (Chambers, 1997).

Notes

Notes2Healers or Dhami Jankri' in Nepal use shamanistic practices to heal their clients.

3A Dhami Jankri' is a traditional healer

BISTA, D B (1996) People of Nepal, Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

BRAY, S and Preston-Shoot, M (1995) Empowering Practice in Social Care, Buckingham: OUP.

BUTLER Flora, C (1997) Enhancing Community Capitals: The Optimization Equation, accessed on 29/4/98 from <http://www.ag.iastate.edu/centers/rdev/newsletter/mar97/enhance.comm.cap.html>.

CHAMBERS, R (1983) Rural Development: Putting the Last First. Harlow: Longman.

COMMISSION of the European Communities (1993) European Social Policy - Options for the Union, Consultative Document, Green Paper, COM (93) 551, Directorate General for Employment, Industrial Relations and Social Affairs, Geneva.

COOPERIDER, D L and Srivasta, S (1997) Appreciative Inquiry in Organisational Life, in Woodman, R and Passmore, W (Eds.) Research in Organisational Change and Development, Volume 1, Greenwich: JAI Press.

DANIEL, A (1988) Politicians, Bureaucrats and the Doctors, Researching the Crossfire, in Action and its Environments: Towards a New Synthesis, New York: Columbia University Press.

EVERITT, A (1996) Epistemology and Values in Voluntary Sector Research (unpublished paper).

FALS-BORDA, O and Rahman, A M (1991) Action and Knowledge, London: IT Publications.

FOUCAULT, M (1980) Power/knowledge, Hertfordshire: Harvester Press.

FRIERE, P (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin.

GIBBON, M (1998) The Use of Formal and Informal Healthcare among Women in Eastern Nepal, Health Care for Women International, 19 (4): 343-360.

HILL Collins, P (1990) Black Feminist Thought in the Matrix of Domination, in (Ed.) Lemert, C, (1993) Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings,Oxford: Westview Press.

HOOKS, b (1994) Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, New York: Routledge.

JUSTICE, J (1986) Policies, Plans, & People: Foreign Aid and Health Development, Berkeley: University of California Press.

KABEER, N (1995) Reversed Realities: Gendered Realities in Development Thought, London:Verso.

KELLY, L, Burton, S and Regan, L (1994) Researching Women's Lives or Studying Women's Oppression? Reflections on What Constitutes Feminist Research, in (Eds. Maynard, M and Purvis, J) Researching Women's Lives From a Feminist Perspective, London: Taylor Francis.

KRANTA, M E (1990) The Health and the Nutritional Status of Girl Children in Nepal with Special Reference to Adolescent Girls and Pregnancy, in, Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Girl Child: A Neglected Majority, Kathmandu, Nepal, pages 53-65.

MCWHIRTER, E M (1991) Empowerment in Counselling, Journal of Counselling and Development, 69: 222-227.

MINGERS, J (1992) Recent Developments in Critical Management Science, Journal Operational Research Society 43 (1): 1-10.

MULLENDER, A and Ward, D (1991) Self-directed Groupwork - Users take Action for Empowerment, London: Whiting and Birch.

ROWLANDS, J (1997) Questioning Empowerment, Oxford: Oxfam.

SEWA - Rural Team (1996) An Experience in the Use of PRA/RRA Approach for Health Needs Assessment in a Rural Community of Northern Gujarat, India, in (Eds.) de Koning, K and Martin, M, Participatory Research in Health, London: Zed Books.

SIGDEL, S (1998) Primary Health Care Provision in Nepal, Kathmandu: Sunita Sigdel.

STEIN, J (1997) Empowerment and Women's Health: Theory, Methods and Practice, London: Zed books.

TONES, K and TILFORD, S (1994) Health Education: Effectiveness, Efficiency and Equity. London: Chapman and Hall.

UNICEF (1996) Children and Women of Nepal: A Situational Analysis, Kathmandu: UNICEF.

WHITE, L., (1994) Development Options for a Rural Community in Belize - Alternative Development and Operational Research, International Transactions of Operational Research 1 (4): 453-462.

WHITE, L. and TAKET, A., (1997) Beyond Appraisal: Participatory Appraisal of Needs and Development of Action (PANDA), Omega 25(5): 523-534.

WHO (1993) Women's Health and Development, London: Jones and Bartlett.

WILLIAMS, S (1995) The Oxfam Gender Training Manual, Oxford: Oxfam.

YUVAL-DAVIES, N (1994) Women, ethnicity and empowerment, Feminism and Psychology, 4 (1): 179-197.