by Jennifer Kettle

University of Sheffield

Sociological Research Online, 21 (4), 6

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/4/6.html>

DOI: 10.5153/sro.4109

Received: 6 Jan 2016 | Accepted: 5 Oct 2016 | Published: 30 Nov 2016

Household work literature has highlighted the importance of mothers to their daughters' accounts of their household work practice, arguing that women can both aim to emulate and avoid particular practices in their own household work. This paper further explores this topic, drawing on a small-scale qualitative study to explore the self-narratives that two generations of mothers construct around the theme of household work. It looks particularly at how accounts of household work practices are incorporated into broader stories of growing up and taking responsibility, and the relevance of discourses of individualisation, and the notion of reflexive biographies to these explanations. This article also draws on theories of connectedness to show how self-narratives around the theme of household work reflect different forms of relationality, and to argue that a concept of relational selves is useful for making sense of these narratives.

1.1 Drawing on a qualitative study exploring the household work[1] narratives of two generations of mothers, this article examines how these were shaped by discourses of individualisation, and also how they can be analysed through a lens of connectedness. The article sets out the theoretical background in terms of individualisation and relational narrative identities, particularly in relation to motherhood, before moving on to show how mothers in this study constructed self-narratives around the theme of household work in terms of remembered, imagined and ongoing relationships. I look at how stories of growing up were framed in terms of developing the sense of responsibility required within an individualised society, while at the same time the mothers I interviewed made sense of their identities as constituted relationally. By considering how household work practices were incorporated into broader self-narratives, I argue for further consideration of household work narratives as a way of developing our thinking on individualisation, connectedness and relational identities.

2.1 Individualisation theorists argue that individuals are compelled to make choices as individuals and reflexively construct their own biographies in order to make sense of this process (Giddens 1991; Beck and Beck Gernsheim 2002). In this context, household work is a source of conflict for contemporary heterosexual couples because the organisation of the mundane activities involved in maintaining a household is closely bound up with the self-image and life projects of men and women (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 2002). In terms of household work then, a reflexive biography would account for practices and division of tasks as the result of an autonomous individual making 'identity choice[s]' (Lash and Friedman 1992: 7) within a couple relationship, as part of a required process of making conscious decisions about their relationships and how they work on a day-to-day basis (Beck-Gernsheim 2002). In theorising the self who makes these choices, Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (2002) and Giddens (1991) emphasise the resulting responsibility placed on individuals for the way in which they make these decisions.

2.2 However, this work has been criticised for misrepresenting the agency to make these decisions as a characteristic of the individual taken out of a relational and structural context (Duncan 2011). Feminist research in this area has highlighted the structural context in which household work takes place (Jackson 1992) and thus a tendency for heterosexual couples to 'fall' into traditionally gendered patterns without negotiation (Van Hooff 2011). While this has been recognised in feminist analysis, in constructing self-reflexive biographies individuals in these relationships can still draw on a felt sense of responsibility for the way in which they divide household work and make decisions about managing this in the context of heterosexual relationships, and Van Hooff's study points to this in the 'justifications' provided by her participants (see also Charles and Kerr 1988; Hochschild 1989; Beagan et al., 2008; Wiessman et al. 2008). Although these responses show how women take on this sense of responsibility, explanations for practices and decisions can involve framing this in a more relational way, accounting for one's own attitude as the result of the behaviour of one's mother. Explanations of partners' attitudes can also involve this sort of framing, and they can include suggesting that a male partner does not do a particular household work task, or does not 'see' that it is necessary, because of the way he was brought up. Other research has shown how women construct biographies in which their mothers play various roles, and participants describe consciously trying to emulate or avoid particular practices in the way they choose to engage in household work (Oakley 1974; Hochschild 1989; DeVault 1991; Pilcher 1994). This article builds on this literature to further explore how mother/daughter relationships continue to be incorporated into self-narratives around the theme of household work.

2.3 Multi-generational research on motherhood has considered how women make sense of their relationships with their mothers, and the ways in which values and practices can be consciously reproduced and changed (Brannen et al. 2004; O'Connor 2011; Thomson et al. 2011). Brannen et al. (2004) explore the transmission of motherhood as an identity, suggesting that women identified with or reacted against their mothers as role models in various ways. While decisions about work and care were partly internalised and framed in terms of personal morals and a felt sense of individual responsibility, such decisions were often explained biographically, and shaped by ongoing relationships which had implications for the process of identification of both people in the relationship. By paying attention to how mothering identities can be understood as relational and in process (Miller 2005), we can explore how connections are made across generations of mothers (Kehily and Thomson 2011). In this context, individualisation can be viewed as a discourse by which people make sense of their lives in their narrative accounts, emphasising autonomy and downplaying structural aspects (Brannen and Nielson 2005). While this may influence the way in which people construct accounts in which they are 'choosing, deciding and shaping' (Beck and Beck-Gernshiem 2002: 22-23), and which emphasise values of independence and self-sufficiency, these accounts also rely on a relational sense of agency and identity (Mason 2004).

2.4 In emphasising relationality, this article draws on the work of Smart (2007), who has argued for employing connectedness as a theoretical lens. This can be set alongside individualisation, in that focusing on how people live their lives while embedded in relationships allows for a consideration of how these relationships are incorporated into accounts of choices and actions, while also allowing for the ways in which people can choose which relationships to maintain and how they can shape and reshape these over time. The overlapping core concepts which for Smart (2007) constitute the interiorities of personal life offer a useful approach for analysing the relational aspects of these accounts, and particularly for reflecting on how the self who is the subject of these narratives is conceptualised.

2.5 The idea of narrative identities uses an idea of a reflexive social self in process (Mead 1934; Jenkins 2008; Jackson 2010) and emphasises how people constantly reconstruct and renegotiate their sense of who and what they are through the stories they tell, both to themselves and to others (Somers 1994; Plummer 1995; Lawler 2014). The telling of stories relies on the use of narrative resources that are culturally available at that moment in time, to someone in that social location (Frank 2010), and thus the individualised narratives of growing up that involve taking more responsibility in terms of household work and becoming independent, as constructed by participants in my study, can be seen as a recognisable way in which incidents could be emplotted in household work narratives.

2.6 However, while narratives can draw on discourses of individualisation, Somers emphasises that our personal narratives are located within 'cross-cutting relational storylines' (1994: 607). Similarly Benhabib (1999) argues that we are born into pre-existing webs of narrative in which we start to learn how to make sense of ourselves, although we have the agency to draw on these narratives to construct our own life stories that make sense to us. Nevertheless, our life stories can be challenged; as Benhabib suggests, the characters in any one person's story are 'also tellers of their own stories, which compete with my own, unsettle my self-understanding, and spoil my attempts to mastermind my own narrative' (1999: 348). Understanding narratives as interconnected in this way means that they remain in process; they cannot have 'closure' because a connected narrative could always have an effect on the way in which one constructs a personal narrative.

2.7 Somers (1994) also points out that narratives are embedded in spatial relationships, and while that is not the focus of this article, I recognise the importance place can have for narrative identities (Taylor 2010). Community has specifically been shown to be relevant in previous studies of generations and household work that focus on class, for example, Luxton (1980) looked at three cohorts of working-class housewives of 'Flin Flon', a mining town in Canada, while Pilcher (1994) explored responsibility for household work across three generations of women living in South Wales. Mannay's (2014) work, which revisits Pilcher's study in contemporary Wales, uses a multi-faceted understanding of place to show how, in a deprived village affected by the loss of local industry, women who have taken on breadwinning roles also feel their 'place' is looking after the family home. This literature offers important examples of relational identities, in the sense that what it means for women to identify themselves as 'the "lazy but breadwinning Welsh mam"' (Mannay 2014: 35) relies on various comparison referents, both remembered and imagined in idealised terms.

2.8 This article argues similarly that household work narratives can be usefully conceptualised as interconnected and constructed in relation to other narratives, and will make a case for looking at the way in which women talk about their household work practices over the life course in terms of relationships to others, drawing on empirical data from a qualitative project exploring household work with two generations of mothers. In particular, this article will focus on how relationships with mothers shape accounts of household work practices, and conversely, the role household work plays within these ongoing relationships between mothers and their adult daughters. Furthermore, if we consider the person engaging in these household work practices over the life course, we can usefully consider the role that household work plays in personal narratives, as a way in which women conceptualise 'growing up'.

2.9 As I suggested above, literature on household work has shown the relevance of mother/daughter relationships and ideas of what it means to be a 'good' mother, when making sense of women's accounts of their housework and foodwork practices (Oakley 1974; Hochschild 1989; DeVault 1991; Pilcher 1994; Bugge and Almås 2006; Curtis et al. 2009; Meah and Watson 2011). However, I would argue that by thinking about household work as part of the personal life of these women, in the sense that it is a something that 'impacts closely' on them (Smart 2007: 28), and their changing sense of self, accounts of both individual responsibility and relational identities can be brought out further through a focus on how self-narratives are constructed around the theme of household work. In particular, the personal life concepts of biography, embeddedness and relationality (Smart 2007) can be usefully deployed to develop an understanding of how household work figures in people's personal lives.

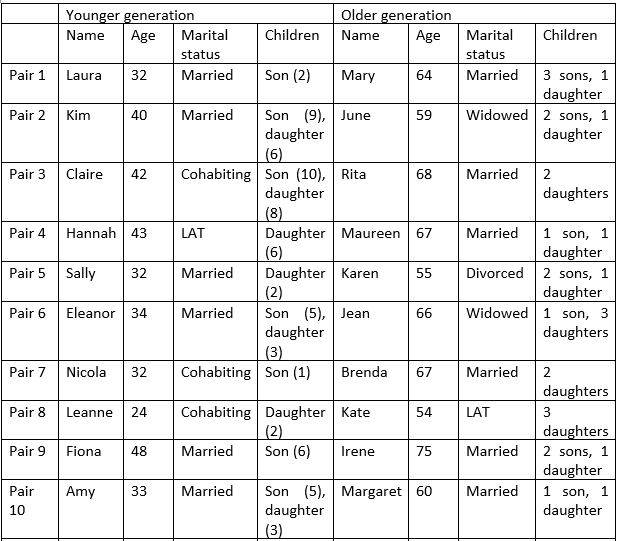

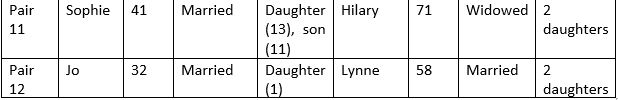

3.1 This article is based upon a study investigating women's household work narratives, and the fieldwork took place between December 2012 and February 2014. Participants were 24 British women who were interviewed individually.[2] This sample was comprised of 12 pairs of mothers and their adult daughters, who were themselves mothers of at least one young child, defined as 0-11 (see Table 1). The use of two generations from 12 families, rather than more strictly defined cohorts, means that there is only 6 years between the oldest younger generation participant, and the youngest older generation participant. While this approach allowed me to compare the narratives of mothers and daughters, and to reflect on intergenerational relations, I am not able to draw any conclusions about the experiences of any particular cohort.

3.2 Initial recruitment (6 participants, pairs 1-3) was through personal contacts, although the women I interviewed were not women I knew personally; other participants were recruited through advertising in schools, nurseries, libraries and on mailing lists. All but one of the interviews took place either at participants' homes, or for some of the older generation participants, at the home of their daughter.[3] Interviews were semi-structured qualitative interviews and lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour 50 minutes. All but one of the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim,[4] and participants (and any other people mentioned) were given pseudonyms which will be used in this article. The project complied with institutional ethical approval guidelines, and before each interview I explained the project and obtained informed consent to conduct the interview and analysis, and for quotes to be used in publications. A key concern for me was that in such a small study, any woman who chose to read any publications would be able to identify herself and her daughter/mother, and I have tried to be sensitive to this in deciding what quotes to include.

| Table 1. Table of Participants |

|

3.3 The women interviewed were white British and heterosexual and all of the younger generation women were middle-class on the basis of their education and/or occupation. Some of the older generation participants could be designated as middle-class in terms of their training and employment in a professional role (six participants) or most recent employment in a managerial role (one participant). The other five participants had histories of no paid employment or part-time paid employment in lower status occupations, but three of these women were or had been married to partners in higher status occupations when they had young children (Jean, Kate and Hilary), while the other two (June and Maureen) were married to partners in manual occupations. Nevertheless, several of the older generation participants, including those who had been employed in middle class occupations, spoke about economic constraints at different times in their lives or growing up in working class families, and this points to the difficulties of unambiguously assigning a class location over time and between generations (Hockey et al. 2007). The participants recruited through personal contacts included pairs of mothers and daughters living in East Midlands, West Midlands and North Yorkshire. The other participants were recruited from different areas within a large city in the Yorkshire and the Humber region. In 8 cases, the daughter saw the recruitment advert and contacted me; in one case a mother contacted me, and her daughter lived in the same large city. Of the 8 daughters who contacted me, 4 of their mothers lived in the same large city; the other 4 lived in Northumberland, East Midlands, North Yorkshire and another part of Yorkshire and the Humber.

3.4 The transcripts were analysed using a Listening Guide approach (Mauthner and Doucet 1998). The first stage of this process involved multiple readings of each transcript with a different focus each time (reading for the plot and reflexive reading; listening for the voice of 'I'; reading for relationships; placing people within cultural contexts and social structures). Data on each of these readings was collated in individual documents for each participant, which included an outline of the overall narrative, recurring phrases and ideas, my reflections on how my experiences related to those of the participant, reflections on the use of different voices (I, we, you etc.) and 'I-poems'[5] produced from the data, reflections on how other people were spoken about and reflections on references to what I interpreted as broader cultural ideas and structural factors. Following this, Nvivo was used to code the data thematically across the sample, using the analysis from the existing readings as a starting point to look for recurring themes, discourses and narratives.

3.5 The Listening Guide approach is based on the Voice-Centred Relational Method, which is designed to 'bring the researcher into relationship with a person's distinct and multi-layered voice' (Gilligan et al. 2006: 255; see also Brown and Gilligan 1992). However, the more sociologically-informed Listening Guide approach, as developed by Mauthner and Doucet, challenges the original intention of accessing an 'interiority' (Brown and Gilligan 1992) through listening to the voices of participants, arguing that, 'All we can know is what is narrated by subjects, as well as our interpretation of their stories within the wider web of social and structural relations from which narrated subjects speak' (2008: 404). A Listening Guide approach lends itself to understanding narrated selves as relational, as reading for the voice of 'I' and how 'I' in the present reflects on 'I' in the past and in potential futures, and noting where the participant shifts between 'I' and other voices (such as 'we', 'you' and 'it'), can allow for a sociological understanding of how participants weave different perceptions of the self into narrative accounts. Hermans (2002) has also argued for considering how one negotiates between different 'I' positions at any given point in time, likening the multi-voiced self to a society reflecting multiple viewpoints. The rest of this paper will explore how participants drew on different discourses in the way they explained their attitudes to household work and accounted for particular practices, and how this was related to reflexive understanding of a self in process.

4.1 The values of independence, responsibility and self-sufficiency were highlighted in various ways across accounts, which influenced how some women talked about their relationships with their mothers. Sally (pair 5, younger generation) talks about the occasions when she has lived with her parents as an adult and describes how,

'I live then as I live on my own, like I take, you know, responsibility and I'll do stuff around the house and I'll bring shopping in so I think she values that and sees that I do, that I don't take advantage of her'.

4.2 This is in contrast to her brothers who 'tend to just fall back into the pattern of like being looked after and being kids'. Sally's contrast between 'responsibility' and being 'looked after', with the latter as something inherently childish, draws on contemporary Western understandings of adulthood in which 'childish dependency on parental care is expected to give way at a certain age to independent adulthood, a pattern inscribed most readily through familial role expectation' (Hockey and James 2003: 167).

4.3 Growing up and becoming an adult is also understood to include thinking more about the effect of one's actions on others, replacing 'self-centredness with responsibility and commitment for self and others' (Blatterer 2010: 13). Nicola constructed a narrative of 'my journey from an absolute scruffbag to, I don't know, a mum', in which she made sense of a process of making an increasing effort to keep her house tidy and increased consideration of other people she lived with as 'starting to grow up a bit really'. As with other participants, her narrative draws on a natural process of maturation, but also constructs an agentic self that was able to think "no, this is it" and change her behaviour as part of a 'finding myself moment'. Reflecting on how Nicola used 'I' in different ways throughout this narrative highlighted how she makes sense of herself growing up, and demonstrates the conflict and negotiation involved between different 'I's in her story (Hermans 2002). For example, she notes how her attitude to tidiness has changed over time, which illustrates how Nicola in the present reflects on the actions and attitudes of Nicola in the past:

'Now it's things start to annoy me and grate on my a bit, whereas before I'd be like "pffft, whatever" and now I'm like "no I can't deal with this" and I'll have moments where I'm like "right, I'll just blitz things", which I never used to do.'

4.4 The recognition that 'blitzing' mess rather than ignoring it was beneficial in the longer term was evident for several women. Other participants spoke about 'keeping on top' of household work by doing a little every day or having a routine for various tasks, and having a system for keeping one's home tidy was presented as allowing more time for enjoyable activities such as spending time with children.

4.5 Similarly, this link between adulthood and responsibility was highlighted in the way that mothers spoke about trying to teach their children to 'think for themselves instead of me telling them what to do' (Eleanor, pair 6, younger generation). In terms of preparing their children to leave home, several younger generation participants emphasised the importance of children being 'independent' and 'self-sufficient', and able to look after themselves and their homes (including being able to cook for themselves, not bringing washing home and managing household finances). As Hockey and James suggest, full membership of Western society is considered in terms of 'autonomy, self-determination and choice' (1993: 3), and this discourse of adulthood shapes what the mothers in my study talk about their children needing to learn.

4.6 Participants also reflected on learning various household work practices from their mothers, such as sewing, cooking and ironing, and teaching these to their children in order to prepare them for leaving home. However, some of the older generation participants explicitly rejected my reference to their mothers (or grandmothers) 'teaching' them things; 'We didn't get taught it as such, you just did it' (Lynne, pair 12, older generation).[6] Reflecting on how she made sense of learning about housework, June (pair 2, older generation) usefully distinguished between being 'taught like "you'll do it this way"' and learning 'by looking and watching'. Expanding on the second of these, she said:

'I think you learn off your mum, to a certain degree. You know with like housework and this that and the other you see what your mum does and as you grow up you tend to do the same so it's like your mum's your […] like your mentor, like you watch her and you do what she does.'

4.7 Other participants also drew on both ways of learning, including accounts of being taught (particularly about food and cooking) and 'watching and imitating' or 'naturally picking up' other tasks, which was sometimes referred to as 'osmosis' (see also DeVault 1991 who similarly found participants using this language to describe learning about foodwork). However, several participants constructed narratives in which they made decisions to engage in household work that their mothers did not, and avoided simply unreflectively 'picking up' the practices they had witnessed growing up. For example, Hilary (pair 11, older generation) and Lynne (pair 12, older generation) spoke about how growing up in untidy houses made them want to achieve tidiness and order in their own homes. Similarly, younger generation participants talked about having different priorities which influenced their own practices, or working out their own systems that suited their lives.

4.8 These accounts can be seen as reflexive biographies, in the sense that each participant is individually making sense of what appear to be potentially conflicting interrelated factors in order to explain things like her attitude to household work and to account for particular practices. It is also evident that participants recognised that individual responsibility for household work practices is valued, and that they are trying to instil this in their children. However, Smart argues that a focus on individualisation directs the sociological researcher towards 'gathering information and evidence about fragmentation, differentiation, separation and autonomy' (2007: 189). By employing connectedness as a theoretical lens through which to view women's household work narratives, this article will move on to explore what Smart's (2007) conceptual approach can offer.

5.1 This section explores how connectedness shaped women's household work narratives: firstly by outlining how participants accounted for their attitudes and behaviour with regard to household work and then by considering the role household work plays in maintaining ongoing relationships (and how household work is incorporated into more problematic narratives of constraint and conflict (Mason 2004)).

5.2 Drawing on the idea of 'linked lives', which views the lives of individuals as meaningful in the context of other lives, (Bengston et al. 2002; Elder 1994), Smart argues that people are embedded in webs of relationships that go beyond couple relationships, stressing the importance of vertical connections to children, previous generations and ancestors (although horizontal ties can also be considered; see Davies 2015). Individuals are seen to be taking forward parts of the past, which can be physical resemblances, skills and personal characteristics, or shared values. Thus people make sense of themselves in relation to others to whom they are linked in this way, which Lawler (2014) sees as the active identity work of 'recognition', between the extremes of complete choice or determinism. The idea of being embedded in relationships influences biographical accounts of oneself which rely on both personal memories and family stories (Thompson 1993). Focusing on narrative identities highlights how participants account for the way they do and think about household work in relation to what are viewed as inherited and 'natural' characteristics that are part of a stable sense of self, but also particular experiences that are emplotted into a biography to explain the practices of the self in the present.

5.3 Sociological work on inheritance shows how various attributes and behaviours are presented as inherited, and understandings of inheritance are developed from a variety of sources and may rely on contradictory discourses in relation to different questions (Edwards 2000). In my research, describing oneself in terms of inherited characteristics also extended to tidiness:

'I think the really interesting thing like with the family dynamic is actually I'm much more like my dad, personality-wise, but I seem to have got Mum's tidying things, whereas my sister is much more like my mum, she's like a mini-me of my mother to look at, the way she talks, everything, but just tidying she seems to have got my father's genes.' (Jo, pair 12, younger generation)

5.4 Jo also described herself as a 'naturally tidy soul', which is also how she presents her mother. The idea of mother and daughter as the same kind of 'soul' evokes a tangible affinity between them that goes beyond simply behaving in the same way (see Mason 2008). As with other participants in this study who use the language of genetic inheritance, Jo's idea that she and her mother are bound in this way allows for a fixing of a close relationship that is used to shape a personal narrative.

5.5 While 'natural' explanations did not resonate for all my participants, it was at least recognised as a way of understanding one's self in relation to household work. For instance, Nicola (pair 7, younger generation), who mentioned an inherited tendency towards untidiness, felt 'it was never something that came naturally' and later talks about making a 'conscious effort' to tidy up when she gets home from work. Nevertheless she says 'I've always just assumed it comes naturally to some people because I'm just, just being rubbish at it and hating it'. Ideas of 'natural' tidiness or untidiness could be read as evidence of different personality types. However, participants combined the language of natural characteristics and personalities with more relational accounts. Kim (pair 2, younger generation) described herself as 'a very organised person, so I kind of let everything get in a mess but it's always put back tidy and a place for everything and everything in its place' and she describes this as her 'personality'. She also links this to her job, explaining these personality traits as 'probably why I do accountancy as well because we tend to be quite [um] rigid people'. This suggests a strong sense of self, rather than behaviour tied to a particular place or context. However, Kim then frames her tidiness in a different way, drawing on a biographical understanding:

'I can't settle if it's not tidy. I blame that on my mum because our house is always, we could play but at the end of the day it was always put back tidy so it's kind of how I've grown up, how my nan was so it's kind of a generation thing in that's how I think we should be.'

5.6 Thus according to her narrative, Kim's 'personality' was partly formed through these family relationships, and allows her to frame her attitude to household work as not simply something she is individually responsible for.

5.7 Across the sample, biographies were seen as relevant to the household work practices of participants. For example, Fiona (pair 9, younger generation) describes how, because her parents 'divided the household work pretty well between them' and had paid help in the form of a cleaner, she and her brothers 'were never given duties or things as kids…we never had anything set'. Fiona suggests that her mother 'had in her mind when we were growing up…that we shouldn't give them [household work tasks] massive importance'. She recalls that her mother 'never offered advice then about getting in a routine with cleaning or anything', and this forms part of a narrative in which she remembers 'not having a very structured routine around it and [um…] never really feeling I was doing it very well' when she had her own place. For Fiona, 'growing up' included learning about the importance of a routine for doing household work, which she worked out when she was living on her own. In terms of her own mothering practices, Fiona emphasises that she wants her son to be involved in household work, and grow up with the 'mentality' that 'there are ways of everybody chipping in to make things better'. This connects her son's biography to her own narrative, in which she has grown up from somebody who felt overwhelmed by things that seemed 'too difficult' to someone who has a clearer sense of what she wants and who acts in particular ways to make things happen (such as actively trying to influence her son's approach to household work).

5.8 Other participants spoke about the biographies of their male partners, and explained their household work practices as adults in relation to how they were brought up. For example, Karen (pair 5, older generation) draws on her remembered experiences with her husband in explaining why she taught her sons to cook in order to prepare them for leaving home:

'I just thought back really to the fact of what my mother-in-law had done and thought that he, you know, John [husband] had come into the marriage with me unable to do anything really and that I didn't really want to put my sons into that situation, I wanted them to be able to do something.'

5.9 Karen's explanation of her husband's behaviour focuses on the role of his mother, and this has shaped how she explains her practices. This emphasis on mothers' roles was evident across several participants' accounts. Amy (pair 10, younger generation) describes how her husband 'wasn't taught to cook, he wasn't taught to clean, he wasn't taught to do anything by his mother', while she and her brother were involved in tasks including cooking, tidying, vacuuming, dusting, and washing and drying up. Amy draws on these biographies to explain their different approaches to household work, and as part of a narrative of her husband 'not noticing' what needs doing in the way that she does and doing cleaning tasks only if asked to do so. Thus her account of being 'selective' in what she asks him to do can be seen as an individual strategy in line with Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (2002), but by analytically drawing attention to connectivity, the way in which Amy makes sense of 'the difference between my husband and I' can be seen in terms of biographical accounts of what their mothers expected and encouraged.

5.10 However, growing up without being expected to do much household work can be part of a different story, as Kim shows:

'I didn't leave home till I was twenty seven and my mum did everything for me. So likewise I do everything for Joe and Molly [laughs]… I think that's kind of where I've kind of become the way I've become because it's kind of, it was always done for me so I expect it to be done for my children, for me to do it.'

5.11 Kim uses this aspect of her childhood as part of her story of why she behaves in the way she does, as other participants do in accounting for the behaviour of the various characters they introduce. These biographical stories can be seen as a way of accounting for one's present self, and thus past events are made sense of as part of a process of forming the self. As Smart (2007) suggests, stories about one's parents can be used in different ways as part of explanations of one's own identification and behaviour. Thus rather than seeing the behaviour of parents, and particularly mothers, as determining the behaviour of children, it is the process of telling the story of one's self that makes sense of these practices, giving them meaning in the context of the plot developed by the storyteller. In her interview then, Kim highlighted her own personality, but framed this in a relational context in which the way she was brought up has influenced her attitude to household work and her practices with her children.

5.12 While Smart's work focuses on personal relationships, what also emerged from my data was a sense in which participants drew on wider networks to emphasise the typicality of their biographies. As part of the second analytical reading (for different voices), I considered how 'you' was used by participants (aside from when it was addressed to me personally). Several older generation participants used 'you' to make sense of what were presented as 'normal' experiences, whether on a day to day basis in terms of household work, or as part of what transitions such as marriage and motherhood meant. For instance, Jean (pair 6, older generation) linked her experiences to other women of a similar age:

'Most of us went from being at home to being married. We didn't go away to university and things so you went from being looked after, and obviously you learn by observing what others are doing so you know, you learnt a lot like that.'

5.13 As well as constructing narratives that showed how they were embedded within a network of personal relationships, which involved comparisons to specific others, participants across both generations commented on ways in which they thought their biographies were likely to be similar and different to those of other, imagined women, who functioned as generalised others (Mead 1934; Holdsworth and Morgan 2007) as in the generalising narratives about the negative behaviour of other families described by Finch and Mason (2000).

5.14 What is evident here, and in the previous section, is that the narratives women construct to explain their household work practices draw on different discourses, including language of individual, autonomous choices and personalities, but also ideas of 'natural' processes across generations, wider shared experiences and practices shaped by particular relationships. While this shows various ways in which household work is linked to a sense of self, the next section will explore how these selves can be understood as not just having relationships and responsibilities, but as relational (Mason 2004).

5.15 The concept of relationality expresses the idea that people are constituted through their close kin ties. As with the other concepts, and in keeping with her theoretical links to Morgan's family practices approach (2011), Smart stresses the active nature of relationality as a constant process, suggesting 'the term relationism conjures up the image of people existing within intentional, thoughtful networks which they actively sustain, maintain or allow to atrophy' (2007: 48). These processes of relationality depend on the quality of relations, not just their existence (Gabb 2008), and previous work has shown how caring acts between people work to maintain the relationship between them (see, for example, Ellis 2013). Finch and Mason's (1993) work on family responsibilities demonstrates that responsibilities between people develop over time through a process of negotiation, rather than being seen as an inherent part of a particular family or kin relationship.

5.16 In this study, the issue of help with, and advice about, household work was discussed in all the interviews, and this emerged as both a positive aspect of particular relationships, and as a source of tension in others. Within most pairs, the older generation participants in this study helped their daughters with household work in various ways, particularly when children were born, but also continuing this alongside providing childcare (for example, Nicola (pair 7, younger generation) spoke about how her mother 'does loads' when she looks after Nicola's son, such as vacuuming, cleaning and washing clothes. As well as practical help, several women also spoke about calling their mothers for recipes or help with cooking, and some mentioned getting advice about other household work tasks such as cleaning curtains or sewing. Following Smart's definition of relationism, these practices are part of the process of identifying as a mother and a daughter, and making sense of what this means in the context of one's personal relationships. Mason (2004) distinguishes between 'selves in relation' and 'relational selves', highlighting that the narrated selves are constituted through an ongoing process of relating to others. Thus the way in which participants as daughters made sense of ongoing help from their mothers reflects an understanding of motherhood as a relational identity, albeit one that changes over the life course of one's children.

5.17 Nicola's mother, Brenda, describes practically helping her daughter with household work, and explains that she does this because 'I see the, part of looking after Alfie is helping Nicola out with other things that she needs doing.' Brenda is identified both as a grandmother to Alfie, and a mother to Nicola, and the household work tasks that she does while looking after Alfie can be seen as mothering in the sense of meeting her daughter's needs (Lawler 2000). Mason et al. (2007) have argued that as parents as well as grandparents, the participants in their study had to achieve a balance between letting their children live their own lives by 'not interfering' and 'being there' to help and support them when this was wanted. Brenda's account shows how she makes sense of doing household work tasks for her daughter in terms of suggesting these were necessary for Nicola's well-being.

5.18 Some participants spoke about an increased closeness with their mothers, which was linked to becoming mothers themselves. Sally (pair 5, younger generation) suggests that her having her daughter Leah 'made us [her and her mother] really close', as they were both able to offer practical help and emotional support (her mother and father had recently split up when Leah was born). While Karen's help is focused on looking after Leah, she recognises 'I don't tend to go there and do housework in the same way'. She links this to when she had young children herself and how she appreciated someone looking after the children because it was nice to be able to 'get on with stuff you want to get on and do it in the way you want to do it'. This may be shaped by how Karen experienced her mum's helping when Karen had young children as in some ways problematic (for example, she mentioned getting 'agitated' that her mother would 'iron everything, absolutely precisely, where I wouldn't have bothered' and describe it as "I'm helping you" despite Karen seeing it as unnecessary). Thus Karen avoids doing tasks such as cleaning as a way in which she can 'not interfere', but at the same time can 'be there' to 'comfort' Sally when she is upset about Leah's behaviour (Mason et al. 2007). Nevertheless, she comments that 'if she asked me, if she said "Mum will you come across and clean for me one day?" then obviously I would'. Therefore if she would be helping Sally and meeting her needs by cleaning, this would fit into the mothering identity she constructs throughout the interview.

5.19 Bearing in mind that relationality is not an inherently positive concept, practical help with housework that was unwanted or that was carried out in a way that contributed to the identification of a daughter or daughter-in-law as a 'bad' wife could worsen relationships. Kate (pair 8, older generation) spoke about a difficult relationship with her mother-in-law, which included criticism of Kate's cleaning ('no matter how clean it was and tidy, she'd always look down her nose and criticise and say "oh I came, I had to do so much, your kitchen was a disgusting mess"') and taking it upon herself to clean items 'to make me feel embarrassed'. This subsequently affected other decisions, such as those around childcare, which was part of a narrative of constraint in which she was not able to continue working in the same job; as she put it, it was 'just not worth it' to ask her mother-in-law to watch her children, because she felt under pressure for the house to be 'spotless' if her mother-in-law was going to see it. Later in the interview, Kate explains how the way she helps her eldest daughter is 'not anything like how it was with my mother-in-law, you know her coming in and looking at vases and washing them to prove a point' which she describes as 'belittling'. Instead she emphasises that she asks her daughter if she wants help; 'I don't just walk in and say "right I shall do this and I'll do that"'. Although this does not relate to being a grandmother (as Jodie does not have children), the idea of not-interfering (Mason et al. 2007) is key here; any help from Kate should be requested or approved by her daughter. Returning to the role of biographies in accounting for women's selves and their household work practices, Kate's explanation of how she helps her daughter with household work is shaped by her experiences with her mother-in-law, and thus how she accounts for her mothering identity in the way in which she maintains her relationship with her daughter is framed biographically.

5.20 Some of the older generation participants reflected on household work as a problematic aspect of their relationships with their adult daughters. Lynne (pair 12, older generation) mentions her daughter Abby who had a 'horrendous' room when she lived at home, but suggests that she saw Abby's untidiness as an immature practice that could be changed. When Abby moved into her own place, Lynne mentioned that 'I really thought it would be lovely and she'd be inviting us occasionally for meals', showing how this relationship is imagined. However, the reality does not match this as she is not invited often (at the time of the interview, Lynne estimates it was nine months ago). From Lynne's account it seems that Abby is particularly concerned about her mother's opinion: 'And if I've got some stuff for her she'll say "can you send me Dad down with that stuff?", I'll say "well no, Dad's not available" "well can you come and keep your eyes shut then?"'. This does not appear to just be Abby's perception; Lynne comments that 'I find it very difficult to bite my tongue' and admits to giving advice like 'well it doesn't take much to keep it tidy like this'. The difficulties in Lynne's mother/daughter relationship with Abby seem to be partly based on expectations that having bought a house, her daughter would 'grow up' (in the sense of developing an identity of a responsible adult) and take care of her home. However, Abby's continued untidiness limits the extent to which she and Lynne can relate as equals, two adult heterosexual women who can enjoy spending time together, having meals in a 'lovely' home. Instead, Lynne appears to be trying to avoid maintaining a parent/child dynamic, but by implicitly trying to avoid being 'told off' for the state of her house, it appears that Abby is continuing to identify her mother as a 'nagging parent' and thus spoil Lynne's self-identification in this regard (Benhabib 1999).

6.1 This article has argued that looking at household work through the lens of both individualisation and connectedness can help us to explore this as part of self-narratives. Values such as self-sufficiency and independence are evident in the narratives participants constructed around household work, which demonstrate how the women I interviewed recognise how they are held responsible as individuals for managing household work practices, and making decisions. In addition, a focus on connectedness highlights various way in which their narrative identities can also be seen as relational, and this in turn shapes the ways that the self who engages in household work practices is conceptualised within these accounts. This article has outlined various other discourses that participants drew on in their self-narratives, including naturalistic links between generations, accounts of direct and indirect socialisation and broader shared experiences. In particular, this article has focused on how looking at the ways in which participants could be seen to be embedded in webs of ongoing relationships shaped how they made sense of their household work practices and how they constructed relational mothering identities through narrative accounts.

6.2 In considering the role household work plays in narrative of 'growing up', this article has also drawn attention to the ways in which household work practices can be incorporated when considering transitions to adulthood. Arguably the focus on household work in this study has shaped the narratives, which are constructed interactionally between the researcher and participant within the interview context (Elliott 2005). Nevertheless, existing literature suggests that adulthood is framed in terms of 'settling down' with a partner and having children (Blatterer 2010; Brooks 2010), and in this study, women's narratives of growing up often linked an increased consideration of, and responsibility for, household work to becoming a wife and mother and 'settling down' in this way. Contemporary understandings of standardised adulthood include independence due to having an income and living arrangements of one's own (Blatterer 2010), and this formed part of the 'growing up' narratives of some participants (such as those who distinguished between household work in student houses and in a home with their partner and children). Thus it may be useful to consider those who are adults in terms of chronological age, but are not cohabiting in couple relationships (such as studies of housemates, or adult children who have returned to live with their parents).

6.3 While this article is based on research with a small, relatively homogenous sample, I would argue that the themes highlighted are worth further exploration in order to continue to develop an understanding of connectedness and personal lives. A focus on self-narratives allows for a consideration of how household work can be incorporated into ways of talking about oneself over the life course, and as I have demonstrated, the seemingly mundane practices involved in household work can be viewed through different lenses. By viewing narratives of household work practices through a lens of individualisation, we can identify accounts of the 'choosing, deciding and shaping' self, while a focus on connectedness highlights ways in which this sense of self is also understood in terms of various remembered, imagined and ongoing relationships.

1 I use 'household work' as a way of referring to 'the sum of all physical, mental, emotional and spiritual tasks that are performed for one's own or someone else's household and that maintain the daily life of those one has responsibility for', following Eichler and Albanese (2007: 248). I find this a useful concept to reflect the ways in which a wide range of tasks were linked in the narratives of the women I interviewed.

2 Although the omission of male participants from this research means it is beyond the scope of this research to comment on how men would account for their household work practices, the research design allowed for a focus on mother/daughter relationships.

3 The other interview took place at the workplace of the participant.

4 Detailed notes were taken at the other interview at the request of the participant.

5 This involves highlighting statements where respondents use personal pronouns and, maintaining the order of the statements, producing I-poems which highlight how the participant constructs a sense of self (Mauthner and Doucet 1998). As Edwards and Weller (2012) have shown, this can be used to capture 'I' in the present and potentially different 'I's in the past.

6 Reflecting on my own preconceptions as part of my analytical approach, I recognise that I have been influenced by cultural shifts in an understanding of parenting, which is increasingly viewed as something that does not happen 'naturally', and which requires the intervention of experts (Lee et al. 2014). The idea that parents are now expected to engage in activities with their children that are in some way goal-orientated (Ramaekers and Suissa 2011) is evident in contemporary discourses of parenting, and in the way I framed my interview questions.

BEAGAN, B., Chapman, G. E., D'Sylva, A. and Bassett, B. R. (2008) '"It's Just Easier For Me to Do It": Rationalizing the Family Division of Foodwork'. Sociology, 42 (4): p. 653-671.

BECK, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002) Individualization. London: Sage.

BECK-GERNSHEIM, E. (2002) Reinventing the Family: In Search of New Lifestyles. Cambridge: Polity.

BENGSTON, V., Biblarz, T. and Roberts, R. (2002) How Families Still Matter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BENHABIB, S. (1999) 'Sexual Difference and Collective Identities: The New Global Constellation', Signs, 24 (2): p. 335-361.

BLATTERER, H. (2010) 'Generations, Modernity and the Problem of Contemporary Adulthood'. In Burnett, J. (ed) Contemporary Adulthood: Calendars, Cartographies and Constructions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [doi:10.1057/9780230290297_2]

BRANNEN, J., Moss, P. and Mooney, A. (2004) Working and Caring over the Twentieth Century: Change and Continuity in Four-Generation Families. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

BRANNEN, J. and Nielson, A. (2005) 'Individualisation, Choice and Structure: A Discussion of Current Trends in Sociological Analysis'. The Sociological Review, 53 (3): p. 412-428. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00559.x]

BROOKS, R. (2010) 'Young Graduates and Understandings of Adulthood'. In Burnett, J. (ed) Contemporary Adulthood: Calendars, Cartographies and Constructions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

BROWN, L. M. and Gilligan, C. (1992) Meeting at the Crossroads: Women's Psychology and Girls' Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674731837]

BUGGE, A. B. and Almås, R. (2006) 'Domestic Dinner: Representations and Practices of a Proper Meal Among Young Suburban Mothers'. Journal of Consumer Culture, 6 (2): p. 203-228.

CHARLES, N. and Kerr, M. (1988) Women, Food and Families. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

CURTIS, P., James, A. and Ellis, K. (2009) '"She's got a really good attitude to food. . . Nannan's drilled it into her": Inter-generational relations within families'. In P. Jackson (ed.) Changing Families, Changing Food, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [doi:10.1057/9780230244795_5]

DAVIES, K. (2015) 'Siblings, Stories and the Self: The Sociological Significance of Young People's Sibling Relationships'. Sociology, 49 (4): p. 679-695.

DEVAULT, M. (1991) Feeding the Family: The Social Organization of Caring as Gendered Work. Chicago, IL and London: The University of Chicago Press.

DOUCET, A. and Mauthner, N. (2008) 'What Can Be Known and How? Narrated Subjects and the Listening Guide'. Qualitative Research, 8 (3): p. 399-409.

DUNCAN, S. (2011) 'Personal Life, Pragmatism and Bricolage'. Sociological Research Online, 16 (4). [doi:10.5153/sro.2537]

EDWARDS, J. (2000) Born and Bred. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

EDWARDS, R. and Weller, S. (2012) 'Shifting Analytic Ontology: Using I-Poems in Qualitative Longitudinal Research'. Qualitative Research, 12 (2): p. 202-217. [doi:10.1177/1468794111422040]

EICHLER, M. and Albanese, P. (2007) 'What is Household Work? A Critique of Assumptions Underlying Empirical Studies of Housework and an Alternative Approach'. Canadian Journal of Sociology. 32 (2): p. 227-258.

ELDER, G (1994) 'Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspectives on the Life Course'. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57 (1): p. 4-15. [doi:10.2307/2786971]

ELLIOTT, J. (2005) Using Narrative in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. London: Sage.

ELLIS, J. (2013) Thinking beyond rupture: continuity and relationality in everyday illness and dying experience, Mortality, 18 (3): p. 251-269. [doi:10.1080/13576275.2013.819490]

FINCH, J. and Mason, J. (1993) Negotiating Family Responsibilities. London: Routledge.

FINCH, J. and Mason, J. (2000) Passing On: Kinship and Inheritance in England. London: Routledge.

FRANK, A. (2010) Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago, IL and London: University of Chicago Press.

GABB, J. (2008) Researching Intimacy in Families. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [doi:10.1057/9780230227668]

GIDDENS, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

GILLIGAN, C., Spencer, R., Weinberg, K. M. and Bertsch, T. (2006) 'On the Listening Guide: A Voice-Centred Relational Method'. In S. N. Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy (eds) Emergent Methods in Social Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [doi:10.4135/9781412984034.n12]

HERMANS, H. J. M. (2002) 'The Dialogical Self as a Society of Mind: Introduction' Theory and Psychology 12 (2): p. 147-60.

HOCHSCHILD, A. (1989) The Second Shift. New York: Avon.

HOCKEY, J. and James, A. (1993) Growing Up and Growing Old: Ageing and Dependency in the Life Course. London: Sage.

HOCKEY, J. and James, A. (2003) Social Identities Across the Life Course. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

HOCKEY, J., Meah, A. and Robinson, V. (2007) Mundane Heterosexualities: From Theory to Practice. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

HOLDSWORTH, C. and Morgan, D. (2007) 'Revisiting the Generalized Other: An Exploration'. Sociology. 41 (3): p. 401-417. [doi:10.1177/0038038507076614]

JACKSON, S. (1992) 'Towards a Historical Sociology of Housework: A Materialist Feminist Analysis'. Women's Studies International Forum, 15 (2): p. 153-172.

JACKSON, S. (2010) 'Self, Time and Narrative: Re-Thinking the Contribution of G. H. Mead'. Life Writing, 7 (2): p. 123-136. [doi:10.1080/14484520903445255]

JENKINS, R. (2008) Social Identity (3rd edn). London: Routledge.

KEHILY, M. J. and Thomson, R. (2011) 'Figuring Families: Generation, Situation and Narrative in Contemporary Mothering'. Sociological Research Online, 16 (4) http://www.socresonline.org.uk/16/4/16.html. [doi:10.5153/sro.2536]

LASH, S. and Friedman, J. (1992) Modernity and Identity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

LAWLER, S. (2000) Mothering the Self: Mothers, Daughters, Subjects. London; New York: Routledge.

LAWLER, S. (2014) Identity: Sociological perspectives (2nd edn) Cambridge: Polity.

LEE, E., Bristow, J., Faircloth, C. and McVarish, J. (2014) Parenting Culture Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [doi:10.1057/9781137304612]

LUXTON, M. (1980) More Than a Labour of Love: Three Generations of Women's Work in the Home. Toronto; Ontario: The Women's Press.

MANNAY, D. (2014) 'Who should do the dishes now? Exploring gender and housework in contemporary urban south Wales'. Contemporary Wales, 27(1): p. 21-39.

MASON, J, (2004) 'Personal Narratives, Relational Selves: Residential Histories in the Living and Telling.' The Sociological Review, 52 (2): p. 162-179.

MASON, J. (2008) 'Tangible Affinities and the Real Life Fascination of Kinship'. Sociology, 42 (1): p. 29-45. [doi:10.1177/0038038507084824]

MASON, J., May, V. and Clarke, L. (2007) 'Ambivalence and the Paradoxes of Grandparenting'. The Sociological Review, 55 (4): p. 687-706.

MAUTHNER, N. and Doucet, A. (1998) 'Reflections on a Voice-Centred Relational Method: Analysing Maternal and Domestic Voices'. In Ribbens, J. and Edwards, R. (eds) Feminist Dilemmas in Qualitative Research: Public Knowledge and Private Lives. London: Sage. [doi:10.4135/9781849209137.n8]

MEAD, G.H. (1934) Mind, Self and Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

MEAH, A. and Watson, M. (2011) 'Saints and Slackers: Challenging Discourses About the Decline of Domestic Cooking'. Sociological Research Online, 16 (2) http://www.socresonline.org.uk/16/2/6.html. [doi:10.5153/sro.2341]

MILLER, T. (2005) Making Sense of Motherhood: A Narrative Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MORGAN, D. H. G. (2011) 'Locating "Family Practices"'. Sociological Research Online, 16 (4). [doi:10.5153/sro.2535]

OAKLEY, A. (1974) The Sociology of Housework. London: M. Robertson.

O'CONNOR, H. (2011) 'Resisters, Mimics and Coincidentals: Intergenerational Influences on Childcare Values and Practices'. Community, Work & Family, 14 (4): p. 405-423. [doi:10.1080/13668803.2011.574869]

PILCHER, J. (1994) 'Who Should Do the Dishes? Three Generations of Welsh Women Talking about Men and Housework'. In Aaron, J., Rees, T., Betts, S. and Vincentelli, M. (eds) Our Sisters' Land: The Changing Identities of Women in Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

PLUMMER, K. (1995) Telling Sexual Stories: Power, Change and Social Worlds. London: Routledge. [doi:10.4324/9780203425268]

RAMAEKERS, S. and Suissa, J. (2011) The Claims of Parenting: Reasons, Responsibility and Society. London: Springer Verlag.

SMART, C. (2007) Personal Life: New Directions in Sociological Thinking. Cambridge: Polity.

SOMERS, M. R. (1994) 'The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach'. Theory and Society, 23: p. 605-649.

TAYLOR, S. (2010) Narratives of Identity and Place, London: Routledge.

THOMPSON, P. (1993) 'Family Myths, Models, and Denials in the Shaping of Individual Life Paths'. In Bertaux, D. and Thompson, P. (eds) Between Generations: Family Models, Myths and Memories. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

THOMSON, R., Kehily, M. J., Hadfield, L. and Sharpe, S. (2011) Making Modern Mothers. Bristol: The Policy Press.

VAN HOOFF, J. (2011) 'Rationalising Inequality: Heterosexual Couples' Explanations and Justifications for the Division of Housework along Traditionally Gendered Lines'. Journal of Gender Studies, 20 (1): p. 19-30.

WIESSMAN, S., Boejje, H., van Doorne-Huiskes, A. and den Dulk, L. (2008) '"Not Worth Mentioning": The Implicit and Explicit Nature of Decision-Making About the Division of Paid and Domestic Work'. Community, Work and Family, 11 (4): p. 341-33 [doi:10.1080/13668800802361781]