by Nick Crossley and Gemma Edwards

University of Manchester; University of Manchester

Sociological Research Online, 21 (2), 13

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/2/13.html>

DOI: 10.5153/sro.3920

Received: 21 Sep 2015 | Accepted: 25 May 2016 | Published: 31 May 2016

In this paper we make a methodological case for mixed method social network analysis (MMSNA). We begin by both challenging the idea, prevalent in some quarters, that mixing methods means combining incompatible epistemological or theoretical assumptions and by positing an ontological argument in favour of mixed methods. We then suggest a methodological framework for MMSNA and argue for the importance of 'mechanisms' in relational-sociological research. Finally, we discuss two examples of MMSNA from our own research, using them to illustrate arguments from the paper.

1.1 In this paper we discuss mixed-method approaches to social network analysis (SNA). There are a number of existing texts addressing this topic. Some posit a qualitative critique of the exclusively quantitative focus in much SNA (e.g. Emirbayer and Goodwin 1994, Knox et.al 2006). Others discuss qualitative methods and ways in which they might be integrated within this focus (e.g. Bellotti 2014, Crossley 2010, Edwards 2010, Hollstein and Dominguez 2014, Mische 2003). Our contribution here is different. We focus upon methodology rather than particular methods; that is, upon the rationale which, for us, underlies mixed method social network analysis (MMSNA). We make a methodological case for MMSNA.

1.2 We begin by challenging an objection sometimes levelled against mixed methods research; namely, that it combines theoretically/epistemologically incompatible elements, leading to incoherence[1]. Against this we argue that in most cases the same method can be made to serve different theoretical/epistemological masters and, conversely, that different methods can be made to serve the same master, working in complementary ways to offer a more penetrating and robust analysis. The work of getting the methods to serve a master, to return to our above point, is methodology. In addition, we argue that the key to maintaining coherence in mixed methods research is ontology rather than epistemology. Specifically, we suggest that a realist ontology lends the idea of mixing methods coherence and even positively demands it.

1.3 In the second section of the paper we move from a broadly realist to a more specifically relational (realist) ontology (see also Crossley 2011). We begin with a brief discussion of Andrew Abbott's (1997, 2001) critique of 'variable analysis' in American (quantitative) sociology (which builds upon that of Blumer 1956). We add to this critique both by discussing the importance of relationality and its absence in variable analysis, and by considering how it might extend to many of the qualitative studies which are more predominant in British sociology. This discussion touches upon issues of individualisation in social research, the logic and importance of case study research, and finally, the concept of 'mechanisms'. Theorists from a number of theoretical camps, including pragmatism, post-rational choice 'analytic sociology' and critical realism, have advocated a focus upon mechanisms in recent years and we argue that the concept is important in relational sociology too, particularly in relation to MMSNA[2]. 'Mechanisms' provide a concrete focus around which a range of different methods can converge in a single, coherent explanatory analysis. A thorough analysis of any relational mechanism generally requires a combination of methods. In the final section of the paper we illustrate this by reference to two examples from our own work.

1.4 Three points of clarification are necessary before we proceed. Firstly, we define SNA as a quantitative approach rooted in graph theory and increasingly also statistics. By SNA we mean the battery of methods and measures outlined by Borgatti et.al (2013), Scott (2000) and Wasserman and Faust (1994), amongst others, and also such statistical approaches as Exponential Random Graph and Stochastic Actor-Oriented modelling (ERGMs and SAOMs; Lusher et.al 2013, Snijders 2001, 2010, Snijders et.al 2010). MMSNA involves combining these methods with qualitative approaches.

1.5 This begs the question of quantitative methods beyond SNA. Might they be included in MMSNA? We cover this in the paper when we note that the assumptions of many standard statistical models regularly used in social science are not met in network data[3], a tension which both precludes mixing with SNA and points to significant problems with the standard statistical approaches, as applied in social science. Whilst we do not seek to incorporate 'standard' quantitative methods here, however, we remain open to this. To the extent that they can be incorporated coherently within a relational, mixed-method methodology, their inclusion is all to the good.

1.6 Secondly, as we define it, SNA comprises various methods of data analysis which are compatible with most standard methods of data gathering; from questionnaire surveys, through semi- and unstructured interviews to observation and archive analysis. One can compile the matrices necessary for SNA from so-called[4] 'qualitative' sources such as archives and interviews, simultaneously deriving 'qualitative' (i.e. non-numerical) insights as one does so. This means that the challenge for MMSNA is to combine qualitative and quantitative observations at the analysis stage of a project. It is a matter of data analysis not data gathering.

1.7 That said, however, whilst 'qualitative' data often admits of quantification, 'quantitative' forms of data gathering such as questionnaire surveys often exclude qualitative analysis by design, making them inappropriate, at least as stand-alone methods, for MMSNA. Given the positive arguments that we make for MMSNA in this paper, we are therefore also calling for social network analysts to at least supplement closed-question surveys with a consideration of qualitative sources, a practice which we believe is missing in much SNA. Indeed, our call for MMSNA is partly motivated by the observation that the qualitative element once common in SNA (e.g. Mitchell 1969) is much less so today, as (admittedly impressive) complex statistical models have become the hallmark of good research and new, automated means of data gathering and mining have afforded quick and easy means of (quantitative) data gathering (see also Crossley 2010). Neglect of the qualitative dimension often renders social-scientific research deeply problematic.

1.8 Thirdly, by 'SNA' we mean whole network analysis. We are keen advocates of ego-net analysis and believe that it can and should be included in relational methodology (see Crossley et.al 2015). However, to keep things simple we are limiting our focus here to whole network analysis.

2.1 Mixing methods is sometimes regarded as problematic because it is believed to involve the combination of incompatible theoretical and/or epistemological principles[5]. We disagree. Researchers bring theoretical/epistemological assumptions to bear in their research and upon their methods. This shapes the way in which they use methods and what they get from them. Methods themselves do not embody epistemological or theoretical assumptions, however, or at least that depends upon what we mean by 'method' and indeed by 'theory'. Implementing any method involves numerous decisions which embed different assumptions within it, potentially also altering and being altered by assumptions imported at other decision points. But different researchers make different decisions, embedding different assumptions in what is, to all intents and purposes, the same method. Methods may have limits in what they can achieve but the same method can be used in a way informed by and consistent with a range of different theories and researchers can think creatively about the limits and uses of the methods they use. The key is not the methods employed but the way they are understood and used.

2.2 Using questionnaire surveys and statistical models does not make a researcher into a positivist, for example, even though some researchers who call themselves positivists view surveys as their method of choice. Realists, who offer some of the most extensive critiques of positivism and empiricism (e.g. Bhasker 1979, Keat and Urry 1975), sometimes use questionnaire surveys and statistical models (Pawson 1989), and Bourdieu, whose research is embedded in the epistemological tradition of Bachelard (2002) and Canguilhem (1994) (see Bourdieu et.al 1991), does too (e.g. Bourdieu 1984).

2.3 Dominant paradigms exist in some cases, of course, involving taken-for-granted, default assumptions regarding the use of a particular method. However, this does not preclude the possibility of making a different choice. Though we will rejoin Andrew Abbott (1997, 2001) in his critique of 'variable analysis', which, he claims, has become the dominant paradigm in American sociology, for example, we do not believe that an overthrow of this paradigm necessitates that we abandon the surveys, statistics etc. that it typically favours, nor even 'variables'. Variables are merely elements of social life that vary. The problem with variable analysis centres upon the way they are (or are not) thought about and used. Used differently, on the basis of different assumptions, they take on a different meaning and value.

2.4 Even findings can be epistemologically reframed and/or made to serve theories different to and critical of those adhered to by the researchers who found them. Merleau-Ponty's (1962, 1965) existential-phenomenological reframing of the findings of behaviourist and experimental (positivist) psychologists and physiologists provides an excellent example of this.

2.5 This is not a laissez-faire argument. Empirical social science involves interpretive, philosophical and theoretical work, which we are calling 'methodology', and we are calling for rigorous methodology in all research. However, methodology is independent of method, at least to some extent, such that what 'the same' method means and does is subject to variation and, more importantly, such that different methods can be combined coherently within the same methodology. But why bother? What is the positive argument in favour of mixing methods?

2.6 Our argument for mixing methods rests upon an ontological premise; namely, Bhasker's (1979) argument that social reality, though dependent upon the actions, perceptions and conceptions of actors, exists independently of the perceptions, conceptions and research of sociologists. Social worlds exist whether or not sociologists exist to analyse them, and whilst the sociological gaze may impose particular perspectives upon and inform interventions within them, the aim of sociology is to explore and understand these worlds as independently existing domains.

2.7 Social worlds outstrip the sociological gaze. As such, there is always more to them than a researcher can hope to capture. However, the sociologist can achieve both a more comprehensive and a more robust perspective by combining the vantage points that different methods afford; adding, cross-checking and, where conflicting data come to light, deepening her analysis by seeking their resolution. This is our positive argument for mixing methods. It allows us to overcome the limitations of individual methods and, where different methods paint different pictures, generates a tension whose resolution deepens our understanding and enriches our analysis.

2.8 Ontology is pivotal to this argument. If we believe that social worlds exist independently of sociology and we understand social research as an attempt to acquire knowledge of those worlds and their properties, then the vantage points which different methods afford are not incommensurable. They are perspectives upon the same underlying reality and, because of this, we both can and should seek to bring them into dialogue, reconciling them where they differ. Such dialogues may occur between different projects but there is no reason why they should not occur within the same project. Indeed this is beneficial because resolving discrepancies deepens our analyses and adds robustness, whilst combining findings adds breadth, comprehensiveness and detail.

2.9 Perspectives may prove incommensurable if informed by different assumptions. However, as we have already suggested, such assumptions are invested in methods by the researcher, not inherent within them, such that rigorous methodological reflection will prevent this. With this said we can turn more specifically to networks and MMSNA.

3.1 In a number of recent papers, Andrew Abbott (1997, 2001) has posited a powerful critique of the relation between theory and methods in sociology. A key focus of this critique is the 'variable analysis' deployed in much quantitative sociology (see also Blumer 1956). Sociological theories typically focus upon actors and their interactions, he observes, whereas (quantitative) sociological methods typically focus upon variables and their interactions. The two foci do not match up and, as a consequence, theory and method are out of sync and poorly placed to inform one another. SNA is amongst the methods that Abbott (1997) considers as a remedy to the problems of variable analysis. Before we discuss SNA, however, we want to briefly develop and extend Abbott's critique.

3.2 A further difficulty of much sociological methodology, insofar as it does facilitate a focus upon the actor, is its tendency to individualise. In variable analysis, social structures, such as gender and social class, are reduced to and essentialised as individual level variables: attributes of the actor. Furthermore, randomised sampling strategies are explicitly intended to eliminate 'dependencies' (that is, social ties) between cases (that is, social actors). Much statistical modelling of survey data assumes that the individuals surveyed are unconnected. Though it is based on solid statistical principles this strategy is absurd from a sociological point of view. Social actors, qua social actors, live amongst and forge ties with one another. This is what it means to speak of social actors and a social world (Crossley 2011). Sociology, as the science of the social world, ought to be focusing precisely upon connection, not removing it from consideration.

3.3 It is not only quantitative sociology that is at fault here. Much qualitative research, particularly interview-based research, aping quantitative research and seeking the same legitimacy, strives for 'unbiased' samples, which often means atomised individual respondents. Furthermore, structural locations, which are invoked to frame and inform quotations or observations (e.g. 'John, black, working-class male in his fifties') are often, as in variable analysis, rendered as individual characteristics (e.g. attributes of 'John'). Likewise, the meanings, perceptions, attitudes and feelings which shape social action are reduced to the individual actor, as a point of origin, when a more likely source is the network of interactions and relations in which each actor is embedded.

3.4 Individualisation is often unavoidable in data gathering. Where we cannot directly observe we usually have to ask and who can we ask but individuals? However, who we ask, in the sense of sampling, and the ways in which we analyse data can allow us to move outwards from individuals, not to society or social structure conceived as a separate 'thing' over and above them, or indeed as a set of variables, but to social worlds as structures of connections between actors which impose constraints upon and open up opportunities for them; society as mutual influence, collective action and inter-agency.

3.5 The importance of SNA lies in the potential it affords for capturing society and social action in this sense. Whether its actor-nodes are children in a playground or nation states exchanging goods on the world stage, SNA attends to patterns of connection, and thus to the social aspect of human life. It allows us to examine the impact of connection and thereby of social structure upon those participating in it, and indeed of the impact of participants' actions back upon structure. Focusing upon structure and connection necessitates a different way of thinking about research, however; a different methodology. In what follows we sketch out certain fundamentals of what this might involve.

4.1 We noted above that many statistical methods assume case-wise independence. One implication of this is that (standard versions of) those methods are unsuitable for use on whole networks, a constraint which has prompted network methodologists to devise network-friendly versions (see Borgatti et.al 2013), alongside more specialised approaches and models addressing SNA-specific matters (Lusher et.al 2013, Snijders 2001, 2010, Snijders et.al 2013)). However, the non-application of standard statistical methods to network data points to deeper differences which are worthy of brief discussion.

4.2 Whilst standard inferential statistics are focused upon the relationship between a sample and the population from which that sample is drawn and which it is believed to represent, the networks analysed in SNA are not usually samples of anything. A whole network analysis aims for a census of a given population: e.g. all 14-18 year olds living on a particular housing estate (Kirke 2006), all workers on a shop-floor (Kapferer 1969), all monks in a monastery (Sampson 1969) or all key participants in a music world (Crossley 2015). And it is focused exclusively upon that population. There is no assumption, as there is in traditional statistical research, that the case or cases under consideration are representative, at least in a statistical sense, of any wider population. There may be a wider population of cases. There are, for example, many more housing estates than the one studied by Kirke, many more monasteries than Sampson's, many more music worlds than those analysed by Crossley. And the network analyst may believe, with good reason, that their findings shed light upon these other cases and indeed upon social networks more generally. In contrast to inferential statistics, however, and even where new statistical methods of network analysis are employed, there is no mathematical basis upon which to infer from the case studied to others.

4.3 In this respect SNA is a case study method and it is perhaps no surprise that many of the areas of social science where it has caught on are areas where case study approaches are common: e.g. the social anthropology of the original Manchester School (Mitchell 1969), where much SNA began; historical sociology, which typically focuses upon delimited places and times (Bearman (1993), Padgett and Ansell (1993)); social movement studies, where individual movements or clusters of movements are taken as cases (Edwards (2014), Diani and McAdam (2003), Crossley and Krinski (2015), Crossley (2007)); organisational studies, which again focus upon specific organisations or industries; and the study of specific, historically and geographically situated music worlds (Crossley 2015, Crossley, McAndrew and Widdop 2015).

4.4 Recognising SNA as a case study approach is important in two respects. Firstly, it signals an opportunity for MMSNA. Case study research is typically mixed-method. Researchers draw upon data from a variety of sources, triangulating observations and building a cumulative picture of their case. SNA can both benefit from this, gaining enrichment from the input of other methods and learning from the practice of mixing methods, and it can contribute, at least where researchers have a relational orientation, by adding something that other methods lack. SNA pioneers, Mitchell (1969) and Barnes (1954, 1969), developed SNA, drawing upon mathematics and specifically graph theory, as a means of coping with the overwhelming complexity of the relational data (who enjoyed ties with whom) they were amassing in their ethnographic case studies, which was proving unmanageable by conventional discursive means. SNA gave them techniques for storing and analysing relational data. It identified, allowed them to explore and, to touch upon a key theme of this special issue, allowed them to visualise emergent (social) structure within these data - both for analytic and communicative purposes (Moody and Healy 2014). SNA can do all of this for case-study research today. Moreover, now visualisation often plays a role within the process of collecting and exploring relational data too. Network diagrams are created and discussed with research participants (Hogan, Carrasco and Wellman (2007), Ryan, Mulholland and Agoston (2014), Tubaro, Casilli and Mounier (2014)).

4.5 Abbott (1997) makes a similar point. He argues for SNA, alongside other mathematically-based techniques, in a paper calling for a return to the case study approach of the Chicago School. The Chicago School had the right idea, in Abbott's view, but today we have new mathematical tools at our disposal which could add further rigour and precision to the approach which they advocated. The variable analysts were not wrong to turn to mathematics and statistics, in this respect, but they borrowed the wrong things and/or used them in a problematic way, losing sight of the subject matter of sociology, as defined in its key theories. Our challenge is to borrow the right things and to use mathematics and statistics, alongside other tools, to practice sociological research in a manner which is consistent with sociological theory, informing and being informed by it.

4.6 Secondly, case study research and SNA as a case study approach tends to work within an explicit spatio-temporal framework and, as such, allows space and time to become analytic foci. Interactivities are embedded in space and time and case study research allows one to perceive and explore this. A further important strand of Abbott's aforementioned critique of variable analysis concerns its failure to address spatial and temporal specificities which are central to social life.

4.7 The retort which variable analysts generally make to such criticism is that the spatial and temporal embedding of case study research, combined with its small sample sizes, limits the generalisability of its findings. However, Abbott's criticism is to some extent levelled at the very aspiration to generalise, suggesting that social life is irreducibly contextual. Moreover, in the final instance, survey research itself is bounded in time and space, often narrowly, such that its own claims to generalisation are, at least in the way it seeks to make them, equally problematic. A sample is sampled from a spatio-temporally bounded population and statistical theory only justifies inference from the former to the latter, not beyond the bounds of the sampled population – a considerable constraint in the context of a globalised and rapidly changing world. The difference between sample-surveys and case studies, in this respect, is not a matter of generalisability but rather of the size of the population or case they focus upon, whether or not they sample from that population and usually also the depth in which they investigate their chosen population (case study research generally facilitating greater depth).

4.8 Recent debates regarding Bourdieu's (1984) Distinction are illustrative of this. Sympathisers and critics alike have asked whether Bourdieu's research, which was based upon data gathered in France in the late 1960s, still applies today and applies outside of France (e.g. Bennett et.al 2009). To the extent that Bourdieu used an appropriate sampling strategy his findings can be legitimately extended to the whole of French society at the time that his survey was conducted but there is no statistical basis upon which to extend them any further, even if they are persuasive ideas which we believe could and should be further extended. In effect, notwithstanding Bourdieu's sampling strategies and sample sizes, Distinction is a case study of French society in the late 1960s, or if that way of putting it seems unhelpful there is no statistical justification for believing that Bourdieu's findings hold beyond French society in the late 1960s (even if there are other good reasons for believing so (see below)).

4.9 This is not a critique of Bourdieu. He was more aware of these limitations than many and exactly the same point applies to any survey. Major sample surveys cover a bigger population than those captured in what we usually think of as case study research but in the context of global sociology even a national survey is highly geographically specific. And as the almost weekly changes in political opinion polls, combined with the felt need to repeat them so frequently both suggest, sample surveys are time-sensitive too. They afford a snapshot. As the statistical significance of such studies extends only to their sampling frames, in the final analysis all sociological research is, if not case study research then at least subject to similar spatio-temporal constraints with respect to (statistically justifiable) generalisation.

5.1 Statistics is not the only basis upon which we might believe that the findings of a study can be generalised, however. If we accept, as sociologists from a number of different theoretical camps have suggested in recent years, that social life is shaped by a limited number of 'mechanisms', then projects which identify and explore such mechanisms have a potentially generalisable application (Gross 2009, McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly 2001, Gorski 2009, Hedström 2005). A thorough and detailed examination of a particular mechanism in one case will contribute to a more general discussion of this mechanism which compares its findings with those of other studies. Importantly, moreover, to return to our main argument, elucidation of such mechanisms will often require a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. These claims need unpacking.

5.2 Advocates of 'mechanisms' argue that sociology is unlikely to discover the 'laws' that its pioneers, inspired by early developments in natural science, aspired to find. Laws, which stipulate what will always happen in situations of a particular type, are generally found in the 'closed systems' of laboratory science but social worlds are 'open systems' and, like the open systems of the natural world, involve the interplay of too many elements to manifest law-like regularities (Bhasker 1979). However, in amongst the flux and unpredictability of open systems we can observe the effect of familiar 'mechanisms'; that is, intelligible and recurrent formal patterns in social interaction which allow us to explain or at least contribute to an explanation of why, in a particular situation, events unfolded in one way rather than another. We cannot predict where or when a mechanism will kick in but when it does it is recognisable, inviting comparison with other situations where it has been observed, and, to reiterate, it helps us explain the course of events in a particular situation.

5.3 'Mechanisms' are central to many critiques of empiricist conceptions of causality. To say that a causes b, in the classic empiricist account, is to say that when a happens b invariably follows or is rendered more likely. There are many problems with this definition (Keat and Urry 1975). In particular, however, rationalists and realists both argue that causality not only entails that b follows a (or is more likely given a) but that a brings about b. This begs the question of how; the mechanism(s) involved. A proper causal explanation requires an elucidation of mechanisms.

5.4 McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly (2001) provide a useful example of this turn to mechanisms in an applied context. They have been primary advocates of 'mechanisms' in the context of social movements research and have adopted the approach in an effort to place dynamic processes of interaction at the centre of the study of 'contentious political episodes'. In their major study, Dynamics of Contention, they reject the possibility of identifying universal laws of social movement mobilisation, looking instead at the interactive processes involved in particular cases, breaking these processes down into the 'mechanisms' they involve and looking for mechanisms that recur across cases. They draw upon fifteen cases of contentious politics, pairing them for comparison in order to draw out common mechanisms (which may combine differently and have different effects in different cases). By comparing cases that may on the face of it appear extremely dissimilar (e.g. the French Revolution and South African Anti-Apartheid), they identify recurrent and important mechanisms for the emergence of contentious politics. Most relevant for our purposes are the 'relational mechanisms' they identify, which involve changes in connections among people, such as the forging of new ties which facilitate brokerage between previously disconnected actors. New brokerage relations, they show, can have important consequences for contentious episodes.

5.5 Our primary interest here is in relational mechanisms; that is, in mechanisms which form within ties, interactions and networks, shaping and affecting the behaviour of those involved and/or mechanisms which contribute to the formation, transformation, shaping and breaking of such ties/networks. Our argument is both that such mechanisms can serve as a common reference point which different methods can converge upon and about which they can 'converse', facilitating MMSNA, and that MMSNA is often necessary if mechanisms, their bases and effects, are to be properly identified and understood. Crudely put, we believe that the quantitative techniques of SNA are crucial for identifying and measuring the properties of networks and for identifying associations between such properties and wider behaviours and factors that might be regarded either as causes or effects of them but we believe that qualitative work is often essential if we are to understand the how and why of such associations. A proper account of mechanisms necessarily involves both elements.

5.6 In isolation, SNA often reduces causality, in an empiricist manner, to statistical associations (albeit in sophisticated ways). Qualitative work is important because it allows us to get beneath these associations to the interactions which bring them about. Qualitative approaches are no better placed to go it alone, however. Without the means of quantification, data handling and analysis SNA affords there are no patterns and associations to explain, and we cannot verify that locally observed interaction tendencies have any effect. Whilst not sufficient for a full analysis of relational mechanisms, therefore, SNA is necessary.

5.7 The best way to elucidate and argue for these claims is by way of example. In what remains of this paper we discuss two extended examples from our own research.

6.1 Our first example centres upon 'homophily'; that is, the tendency, widely observed across a diverse range of contexts, for social actors to disproportionately forge ties with others who are similar to them in some salient respect (McPherson et.al 2001). Homophily is often treated as a mechanism which can be used to explain higher level processes. We do not dispute the appropriateness of this. However, we believe that SNA sometimes reduces homophily, in empiricist fashion, to a statistical tendency. Against this, drawing upon the abovementioned critiques of empiricism, we suggest that it is only legitimate to speak of a homophily mechanism or mechanisms when we can identify both a statistical tendency and the interactivities which bring it about. This will become clearer in what follows.

6.2 In a recent paper, Ibrahim and Crossley (forthcoming) explore 'political homophily' (a form of what Lazersfeld and Merton (1964) call 'value homophily') within a student political world: student politicos disproportionately form ties to other politicos with similar outlooks to themselves (see also Crossley and Ibrahim 2012). This sounds obvious but its nuances are interesting and it allows us to explain how different methods can converge in the exploration of a relational mechanism.

6.3 Ibrahim and Crossley initially identified political homophily in their network by qualitative means. It was evident from observation that activists tended to cluster in ways which appeared to be related to their political orientation and this observation was supported and elaborated in interviews. Furthermore, qualitative analysis was a crucial means of identifying the political orientations and divides involved. Specifically, although tie formation was related to the parties and groups to which students belonged, homophily appeared to operate at a more general level. Qualitative analysis suggested that there was a basic divide between those activists committed to what McAdam et.al (2001) call 'contentious politics' (e.g. direct action and protest) and those committed to less confrontational and more orthodox forms of political engagement. In addition it suggested a divide within the contentious camp between Trotskyists and 'new social movement' activists.

6.4 This qualitative impression was strong but imprecise and, having hypothesised the pattern, the researchers were concerned that their confirmatory evidence may be an effect of selective observation and interpretation. A more rigorous test was required. They began with an E-I analysis[6] (see Crossley et.al 2015, p.80-90). This revealed clear evidence of strong and statistically significant political homophily, as defined. It also suggested that in-group ties were less homophilous amongst 'mainstream' activists than within either of the two 'contentious' camps, thereby adding nuance to the initial observation.

6.5 This was followed by a series of further E-I analyses focused upon other aspects of activists lives and identities and a (network friendly) logistic regression model combining those which showed a statistically significant impact. The logistic regression analysis suggested that transitivity[7] was the strongest factor in play within the network, and also pointed to the importance of the political groups to which students belonged, their gender and the length of time they had been a student at Manchester. However, it upheld the hypothesis about value homophily based upon political orientation, showing that it retains a strong and significant effect upon tie formation even when other factors are taken into account.

6.6 The use of SNA and network statistics is important in this context because it afforded the researchers a rigorous way of testing the hypothesis of political homophily that they had formed on a qualitative basis. This was partly a matter of using SNA to handle the complexity of their relational data. Their network of 53 activists involved 276 ties and 1102 pairs of actors who could have formed a tie but did not. Add in the political identities of the 53 activists and there is clearly more information here than one could hope to process qualitatively. Like Mitchell and his colleagues (see above), Ibrahim and Crossley needed mathematical assistance. Secondly, it was a matter of having a well thought out and agreed upon method (such as E-I analysis or logistic regression) which allows one to decide whether or not there is homophily in a network. Finally, in the case of the logistic regression analysis, it was a matter of controlling for the fact that other forms of homophily and other network mechanisms were in play in the situation and might be confounding observations.

6.7 However, E-I analysis and logistic regression only identify statistical associations. They do not identify the processes generating those associations. Homophily, as a statistically verified tendency may help to explain other aspects of a network or events within the wider context of that network but it stands in need of explanation itself. As we argued above, causal explanation by way of mechanisms requires that we go beyond associations to explain how and why they come about. For Ibrahim and Crossley, addressing this question necessitated returning to their qualitative data. They sought to unpack the process whereby ties were formed and alters selected.

6.8 This is not the place to discuss their analysis in detail. Suffice it to say that they discovered evidence of a number of different processes. Some, such as the 'foci' described by Feld (1981), were structural; activists' political orientations drew them to time-spaces where they were disproportionately likely to meet others with similar orientations. No active discrimination was involved. Others, such as 'typifications' (adapted from Schutz (1972)), did involve discrimination; activists were variously drawn to and repelled from potential alters on the basis of acquired preconceptions of their 'type'. Some centred upon attraction between those who are similar, others on repulsion between those whose orientations differed. The key point here is that the associations verified by E-I and logistic regression models were generated in a variety of ways not observable with those models or indeed by quantitative means at all. Qualitative analysis was required to identify the processes generating the patterns which these mathematically-based analyses captured. Furthermore, this analysis suggested that there is not one homophily mechanism but several.

6.9 Having turned from qualitative analysis to SNA in an effort to look for systematic evidence of homophily, in other words, the researchers returned to it to further explore the homophily they now knew to exist and discovered that it was an effect of a number of different mechanisms. In this case analysis stopped at that point. However, the return to the qualitative data might have suggested further hypotheses which could be tested quantitatively, and so on; each turn in the back and forth between methods further fine tuning the analysis.

6.10 It might be objected that what we are reporting here is 'merely good practice'[8]. However, to recap some of the arguments of our paper, the practice is only possible because Ibrahim and Crossley gathered and analysed qualitative as well as quantitative data; because they mixed methods. In the absence of qualitative data, such as we find in many contemporary network studies, they would have been limited to empiricist claims about homophilic associations and/or guesswork regarding generative mechanisms. Furthermore, the integration of the two forms of analysis was facilitated by way of a focus upon real mechanisms. Mechanisms, assumed to exist in the political world under consideration, independently of the researchers, provided a shared point of reference upon which the different methods used could converge and about which they could 'talk'.

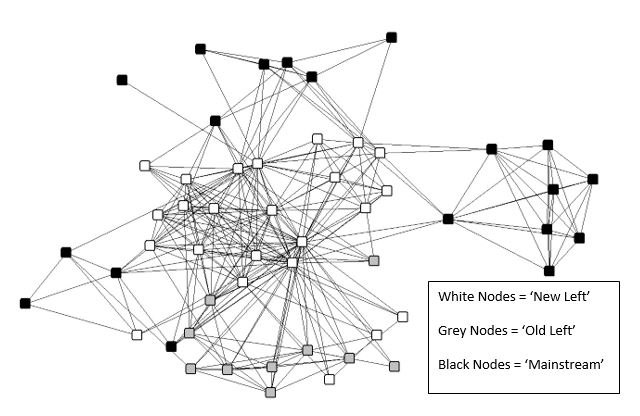

6.11 As a final point on this example consider Figure 1, where the network analysed by Ibrahim and Crossley is visualised and its nodes coloured according to political orientation. Note that whilst the Trotskyist and new social movement activists each form a single cluster (more or less), the mainstream activists form a number of discrete clusters which connect to the wider network at different points. This is not the place to discuss the whys and wherefores of this observation. It is interesting, however, given the focus upon visualisation in this special issue, because it shows how visualisation can contribute to MMSNA. The graph renders the finding that mainstream activists have a lower density of in-group ties (noted above) more intelligible because it shows that the mainstream category combines discrete clusters of activists. This, of course, is a stimulus to further analysis, both quantitative and qualitative, to discover what those distinctions are.

|

| Figure 1. Political Homophily in a Student Political World |

7.1 Our second example is drawn from our research on suffragette networks (Edwards and Crossley 2009, Edwards 2014). It concerns the process of diffusion, and the mechanisms that drive it. A large body of literature exists on this topic, especially around the diffusion of innovations, i.e. how new ideas and practices spread within a population (Coleman et al 1966, Granovetter 1978, Strang 1991, Oliver and Myer 1998, Valente 1995). In the context of our research on the suffragettes, diffusion is important because it has been highlighted as a process that spreads contentious political ideas and practices through social networks (McAdam et.al 2001, Givan et al 2010). Edwards (2014) therefore uses MMSNA to investigate the relational mechanisms driving the spread and adoption of suffragette militancy in the campaign for Votes for Women in the UK (1903-1914), which included tactics like getting arrested and imprisoned and, later on, window-smashing and arson.

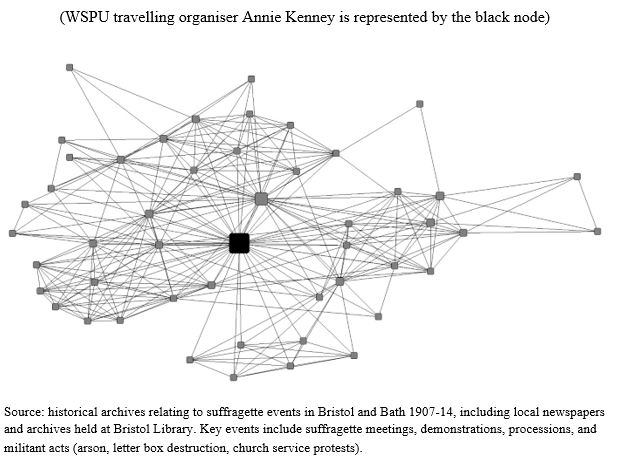

7.2 The first aim of the study was to explore how the diffusion of suffragette militancy is affected by the structure of social networks. Diffusion in this case is taken as a process that can be broken down into the various relational mechanisms that produce it, like those that bring about changes in the nature of connections among people and groups (McAdam et.al 2001). One such mechanism identified as important to the diffusion of suffragette militancy is brokerage, whereby the structure of social connections is altered by nodes that connect previously unconnected people together. The identification and analysis of brokerage was aided by visualisation. Edwards produced visualisations of suffragette networks and used SNA 'betweeness scores' (which measure the extent to which a node mediates the relationship between other nodes in the network), to find that this brokerage role was primarily fulfilled by paid activists of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), who acted as 'travelling organisers'. These organisers moved around the country to mobilise new areas, and in the process opened up channels through which the tactics of the WSPU could spread (for a similar finding relating to the diffusion of the Swedish Democratic Party, see Hedstrom 2000). Figure 2 shows a visualisation of the suffragette network in Bristol and Bath, which presents relational data generated from two-mode data on the co-participation of women in suffragette events in the area between 1907 and 1914. The visualisation usefully identifies and communicates the central brokerage role played by WSPU travelling organiser Annie Kenney (the black node with the highest betweeness score).

|

| Figure 2. The network of women involved in key suffragette events in Bristol and Bath, 1907 to 1914, nodes sized by betweeness centrality |

7.3 Alongside visualisations, Edwards (2014) uses qualitative data from historical archives (including letters, diaries and speeches) to investigate how the content of social relationships shaped the diffusion of militant tactics. Having a connection to one of the WSPU travelling organisers provided interactions through which controversial tactics were talked about, contended, and persuaded. Such was the case in Bristol and Bath when Annie Kenney arrived and brought with her inspirational ideas about militancy and concrete opportunities for discussion and involvement. Qualitative data showed that the diffusion of militancy was a complex process however, requiring attention to other relational mechanisms. Importantly, it cannot be assumed that the formation of a militant suffragette network in Bristol and Bath meant that the local pool of engaged women 'caught' militant ideas like a disease. While 'contagion through cohesion' (i.e. through direct ties) may be a mechanism of diffusion in some cases, the spread of social and political practices is a more complex one.

7.4 To explore mechanisms of social influence, Edwards finds it useful to refer to Burt's (1987) notion of diffusion by 'structural equivalence', which suggests that people are not automatically influenced by their direct ties, but are instead selectively influenced by ties that are socially similar. This mechanism of social influence has been associated with the spread of political tactics in other studies (Soule 1997). SNA is able to provide a precise measure of social similarity through the use of structural equivalence models. These models, used by Burt (1987), identify the nodes in a network that are in a structurally equivalent position vis-a-vis third party ties. It is the competition with regards to maintaining third party contacts that Burt argues leads people to be influenced by those in a structurally similar position (a kind of keeping up with the Joneses effect).

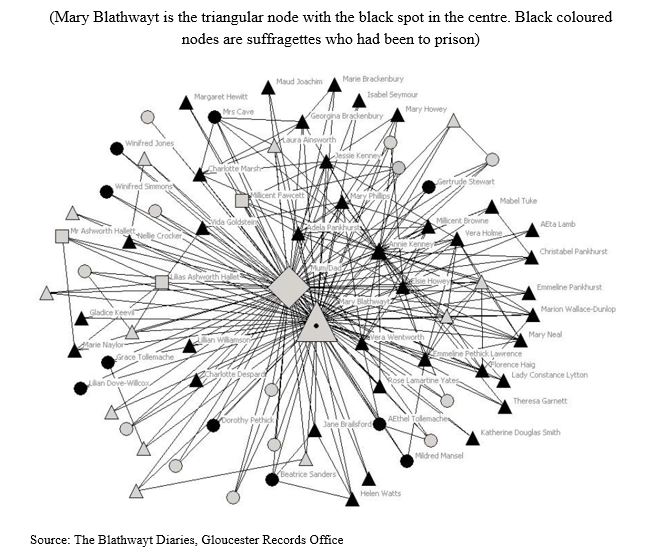

7.5 Following Burt, data from the diary of Bath suffragette Mary Blathwayt showed that social influence was exerted in her network not through direct ties, but through ties to those who were seen as socially similar to herself. Her network is visualised in figure 3 below. While the visualisation shows that she had extensive direct contact with a high number of militant suffragettes, her diary narrates how she was most influenced in her own actions by what other prominent upper class women in the Bath community 'like her' were doing, and they were very much expected to refrain from militancy themselves even if they supported the movement. Visualisations of relational data cannot therefore tell the whole story. In figure 3, Mary Blathwayt is embedded in a highly militant network (black nodes are those who had been to prison), but what it does not tell us is that she always retained a symbolic distance from militancy. Qualitative data are needed alongside network visualisations to explore the complexity of the mechanisms that drive not just the patterns on show, but their interactive consequences.

|

| Figure 3. Bath Suffragette Mary Blathwayt's personal network July 1909-1913 (nodes sized by betweeness centrality) |

7.6 Part of the complexity that qualitative data can open up is the cultural dimension of social networks. Whenever we talk of 'relational mechanisms' we are talking of things that are as cultural as they are structural because what enables and arises from the processes of interaction that we can visualise are shared cultural products (discourses, ideologies, and identities). Data from historical archives revealed an ambiguous discourse surrounding militant tactics in Bristol and Bath, and a questioning of their legitimacy. It was this cultural content of ties that played an important role in tempering the effect on women of the presence of a highly militant suffragette network (like the one shown in figure three). Diffusion processes, then, are driven by relational mechanisms that are both structural and cultural and can be investigated in MMSNA. Brokerage mechanisms reconfigure social ties, and social influence mechanisms make them matter for what people think and do.

8.1 The social world, qua 'social', is constituted by interaction, ties and thereby networks between social actors, both human and corporate[9]. Furthermore, actors are themselves formed and shaped in this process (Crossley 2011). Such connections create conditions within which certain relational mechanisms can emerge which, in turn, make further outcomes and events more (or less) likely. Like social/symbolic interaction itself these processes and mechanisms depend upon the perceptions/conceptions of the social actors involved but in most cases they exist independently of the perceptions/conceptions of sociologists, who therefore approach them as elements of an external, independently existing reality.

8.2 Sociological methodologies need to be attuned to the relational nature of social reality and the methods which collectively comprise SNA are, for this reason, of great importance. However, many different methods can be brought together coherently within a relational methodology. The way in which methods are used and thought about is the key to a consistent methodology, not the methods adopted per se. And mixing methods can be valuable because different methods afford different vantage points upon social relations and their mechanisms, such that their combination affords the researcher a more comprehensive and robust perspective.

8.3 Quantitative methods allow researchers to explore: patterns of connection; statistically significant biases in those patterns; and associations between those patterns and other social facts which might variously explain or be explained by them. This is vital. However, prior qualitative analysis can provide important clues to guide this analysis and subsequent qualitative analysis is often necessary if the researcher is to identify and explore the mechanisms generating these patterns. A satisfactory analysis of mechanisms requires that we can identify both patterns of connection/interaction and their explanations. Quantitative techniques are usually more useful for the former and qualitative techniques for the latter.

8.4 A focus on mechanisms is sometimes objected to on the grounds that its very language evokes a picture of 'cogs in a wheel' that is the antithesis of agency and ignorant of culture. The two research examples that we have presented here show that this does not have to be the case. Culture is not lost in a focus upon mechanisms. Instead, as McAdam and Tarrow (2011, 6) argue, it is embedded within them; especially in the kind of 'relational mechanisms' that MMSNA is focused upon. Our approach also shows that a focus on mechanisms does not have to reduce agents to cogs in the wheel of pre-wired processes. Mechanisms should not be thought of as replacing universal laws with something equally deterministic. They come in different combinations, and have different effects, depending upon the context of the case. But most importantly, they are processes of and tendencies within interaction. It is our view that relational mechanisms are able to point us to complex interplays of (inter)action, and not simply to the uniform and predictable effects of the structure of that (inter)action.

1 We have encountered this response on numerous occasions at seminars and conferences and, again in our experience, it is a frequently voiced worry of postgraduate students who have been advised to choose their research methods and support this choice on epistemological grounds.

2Abbott (2007) is critical of 'mechanisms' but his focus upon 'processes' is very similar and we do not agree with his claim that 'mechanisms' entail methodological individualism. Mechanisms can be relational, as we discuss in this paper (see also McAdam et,al 2001).

3 Most obviously standard tests of significance assume that cases are randomly selected from a wider population and are independent of (i.e. not tied to) one another. Networks are precluded by definition.

4 Qualitative sources are often criticised as subjective but of course questionnaire design is subjective and so too is the act of filling in a questionnaire, even if the numerical outputs of the latter can be expressed in numerical form and exclude 'qualitative' nuances.

5 See note 1.

6 An E-I analysis examines the ratio of in-group to out-group ties within a network (based on a categorical attribute) and generates a probability value for this ratio arising by chance.

7 That is, the tendency for nodes to form new ties to alters who enjoy ties with their existing alters ('friends of friends').

8 Thank you to referee 1 for this.

9 E.g. organisations such as firms, governments and trades unions.

ABBOTT, A. (1997) Of Time and Space, Social Forces 75(4), 1149-82 [doi:10.1093/sf/75.4.1149]

ABBOTT, A. (2001) Time Matters, Chicago, Chicago University Press.

ABBOTT, A. (2007) Mechanisms and Relations, Sociologica 2, http://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.2383/24750.

BACHELARD, G. (2002) The Formation of the Scientific Spirit, Bolton, Clinamen.

BARNES, J (1954) Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish, Human Relations (7), p. 39-58 [doi:10.1177/001872675400700102]

BARNES J. (1969) Networks and Political Process. In Mitchell, J. C. (ed.) (1969) Social Networks in Urban Situations, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

BEARMAN, P. (1993) Relations into Rhetorics, Rutgers University Press.

BELLOTTI, E. (2014) Qualitative Networks: Mixing Methods in Social Research, London, Routledge.

BENNETT, T, Savage, M, Silva, E, Warde, A, Gayo-Cal, E, Wright, D (2009) Culture, Class, Distinction, London, Routledge.

BHASKER, R. (1979) The Possibility of Naturalism, London, Routledge.

BLUMER, H. (1956) Sociological Analysis and the Variable, American Sociological Review 21, p. 683-90. [doi:10.2307/2088418]

BORGATTI, S, Everett, M, and Freeman, L, (2002) Ucinet 6 for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis, Harvard, MA, Analytic Technologies.

BORGATTI, S.P, Everett, M.G. and Johnson, J. (2013) Analysing Social Networks, London, Sage.

BOURDIEU, P. (1984) Distinction, London, Routledge.

BOURDIEU, P, Chamboredon, J-C and Passeron, J-C (1991) The Craft of Sociology, Berlin, de Gruyter.

BURT, R. (1987). Social contagion and innovation: Cohesion versus structural equivalence. American Journal of Sociology, 92, p. 1287-1335. [doi:10.1086/228667]

CANGUILHEM, G. (1994) A Vital Rationalist, New York, Zone.

COLEMAN, J. S., Katz, E., & Menzel, H. (1966). Medical innovation: A diffusion study. New York, NY: Bobbs-Merill Co.

COLEMAN, J. (1988) Free Riders and Zealots: the Role of Social Networks, Sociological Theory 6(1), p. 52-7. [doi:10.2307/201913]

COLEMAN, J. (1990) Foundations of Social Theory, Harvard, Belknap.

CROSSLEY, N. (2015) Networks of Sound, Style and Subversion: the Punk and Post-Punk Worlds of Manchester, London, Liverpool and Sheffield, 1975-1980, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

CROSSLEY, N. (2011) Towards Relational Sociology, London, Routledge.

CROSSLEY, N. (2010) The Social World of the Network: qualitative aspects of network analysis, Sociologica 2010 (1), http://www.sociologica.mulino.it/main.

CROSSLEY, N. (2007) Social Networks and Extra-Parliamentary Politics, Sociology Compass 1(1), 222-236. [doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00003.x]

CROSSLEY, N, Bellotti, E, Edwards, G, Everett, M, Koskinen, J, and Tranmer, M. (2015) Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets, London, Sage.

CROSSLEY, N, and Krinsky, J. (eds) (2015) Social Networks and Social Movements, London, Routledge. [doi:10.1177/0038038511425560]

CROSSLEY, N. and Ibrahim, J. (2012) Critical Mass, Social Networks and Collective Action: the Case of Student Political Worlds, Sociology 46(4), 596-612

CROSSLEY, N, McAndrew, S, and Widdop, P. (2015) Social Networks and Music Worlds, London, Routledge. [doi:10.1093/0199251789.001.0001]

DIANI, M. and McAdam, D.(eds) (2003) Social Movements and Networks, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

EDWARDS, G. (2010) Mixed Methods Approaches to Social Network Analysis, National Centre for Research Methods (UK) Review Paper. [doi:10.1080/14742837.2013.834251]

EDWARDS, G. (2014) Infectious Innovations? The Diffusion of Innovation in Social Movement Networks, the Case of Suffragette Militancy, Social Movement Studies 13(1), p. 48-69. [doi:10.1177/205979910900400104]

EDWARDS, G., & Crossley, N. (2009). Measures and meanings: Exploring the ego-net of Helen Kirkpatrick Watts, militant Suffragette. Methodological Innovations Online, 4, p. 37- 61. [doi:10.1086/230450]

EMIRBAYER, M. and Goodwin, J. (1994) Network Analysis, Culture and the Problem of Agency, American Journal of Sociology 99, p. 1411-54. [doi:10.1086/227352]

FELD, S. (1981) The Focused Organization of Social Ties, American Journal of Sociology, 86(5), p. 1015-1035. [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511761638]

GIVAN, R. K., Soule, S. A., & Roberts, K. M. (Eds.). (2010). The diffusion of social movements, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [doi:10.1163/ej.9789004165694.i-450.48]

GORSKI, P. (2009) Social "Mechanisms" and Comparative Historical Sociology: A Critical Realist proposal, in Hedstrom, P. and Wittrock, B. (2009) Frontiers of Sociology, Leiden, Brill, p. 147-97. [doi:10.1086/225469]

GRANOVETTER, M. (1978). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, p. 1360-1380. [doi:10.1177/000312240907400302]

GROSS, N. (2009) A Pragmatist Theory of Social Mechanisms, American Sociological Review 74(3), p. 358-79. [doi:10.1086/303109]

HEDSTROM, P. (2000). Meso-level networks and the diffusion of social movements: The case of the Swedish social democratic party. American Journal of Sociology, 106, p. 145-172. [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511488801]

HEDSTRÖM, P. (2005) Dissecting the Social, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [doi:10.1177/1525822X06298589]

HOGAN B., Carrasco J.A., Wellman B. (2007). Visualizing personal networks: working with participant-aided sociograms. Field Methods, 19: p. 116-144.

HOLLSTEIN B. and Dominguez S. (eds.) (2014), Mixing Methods in Social Network Research, Cambridge University Press.

IBRAHIM, J. and Crossley, N. (forthcoming) Network Formation in Student Political Worlds, in Brooks, R. (forthcoming) Student Politics and Protest: International Perspectives, London, Routledge.

KAPFERER B (1969) Norms and manipulation of relationships in a work context, in Mitchell J., C., (ed.) (1969), Social Networks in Urban Situations, Manchester University Press, Manchester.

KEAT, R. and Urry, J. (1975) Social Theory as Science, London, Routledge. [doi:10.1057/9780230627628]

KIRKE, D. (2006) Teenagers and Substance Abuse, London, Palgrave. [doi:10.1080/03085140500465899]

KNOX, H., Savage, M. and Harvey, P. (2006) Social networks and the study of relations: networks as method, metaphor and form, Economy and Society, 35(1), p. 113-140.

LAZARSFELD, P. And Merton, R. (1964) Friendship as Social Process, in Berger, M, Abel, T, and Page, C. (1964) Freedom and Control in Modern Society, New York, Octagon Books, p. 18-66.

LUSHER, D, Koskinen, J. and Robins, G. (2013) Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [doi:10.1017/CBO9780511805431]

MCADAM, D., Tarrow, S. and Tilly, C. (2001) Dynamics of Contention. New York: Cambridge University Press.

MCADAM, D. and Tarrow, S. (2011) 'Introduction: Dynamics of Contention 10 years on', Mobilization,16(1): p. 1-10. [doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415]

MCPHERSON, M, Smith-Lovin, L and Cook, J. (2001) Birds of Feather: Homophily in Social Networks, Annual Review of Sociology 27, p. 415-44.

MERLEAU-PONTY, M. (1962) The Phenomenology of Perception, London, Routledge.

MERLEAU-PONTY, M. (1965) The Structure of Behaviour, London, Methuen. [doi:10.1093/0199251789.003.0011]

MISCHE, A. (2003) Cross-Talk in Movements, in M. Diani and D. McAdam (eds.) Social Movements and Networks, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

MITCHELL, J.C. (1969) Social Networks in Urban Situations, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

MOODY, J.W., Healy, K. (2014), Data Visualisation in Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology Vol. 40 (August)

OLIVER, P. And Marwell, G. (1993) The Critical Mass in Collective Action, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

OLIVER, P., & Myers, D. (1998). Diffusion models of cycles of protest as a theory of social movements. Paper prepared for presentation at the session on "Describing, analyzing and theorizing social movements" of Research committee 48, Social movements, collective action, and social change, at the Congress of the International Sociological Association, Montreal, July 30, 1998. [doi:10.1086/230190]

PADGETT, J and Ansell, C (1993) Robust Action and the Rise of the Medici, 1400-1434, The American Journal of Sociology, 98 (6), p. 1259-1319. [doi:10.4324/9780203393338]

PAWSON, R. (1989) A Measure for Measures, London, Routledge. [doi:10.5153/sro.3404]

RYAN L., Mulholland J., Agoston A. (2014). Talking ties: Reflecting on network visualisation and qualitative interviewing. Sociological Research Online, 19(2): 16

SAMPSON, S. (1969) Crisis in a Cloister, unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cornell University.

SCHUTZ, A. (1972) The Phenomenology of the Social World, Evanston, Northwestern University Press.

SCOTT, J. (2000) Social Network Analysis: A Handbook, London, Sage.

SNIJDERS, T. A. B. (2010) Actor-Based Models for Network Dynamics. Working paper http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/~snijders/PoliticalAnalysis_NetDyn.pdf. [doi:10.1111/0081-1750.00099]

SNIJDERS, T. A. B. (2001) The statistical evaluation of social network dynamics, pp. 361-395 in Sobel, M. E., Becker, M.P., (eds.) Sociological Methodology. Blackwell, London. [doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2009.02.004]

SNIJDERS, T. A. B., G.G. van de Bunt, and C.E.G. Steglich (2010) Introduction to stochastic actor-based models for network dynamics. Social Networks 32(1), p. 44-60. [doi:10.1093/sf/75.3.855]

SOULE, S. (1997). The student divestment movement in the United States and tactical diffusion: The Shantytown Protest. Social Forces, 75, p. 855-883. [doi:10.1177/0049124191019003003]

STRANG, D. (1991). Adding social structure to diffusion models: An Event history framework. Sociological Methods Research, 19, p. 324-353. [doi:10.1177/1525822X13491861]

TUBARO P., Casilli A.A., Mounier L. (2014). Eliciting personal network data in web surveys through participant-generated sociograms. Field Methods, 26 (2): p. 107-125.

VALENTE, T. (1995) Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations, New Jersey, Hampton.

WASSERMAN, S and Faust, K. (1994) Social Network Analysis, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.