Occupational Mobility at Migration - Evidence from Spain

by Mikolaj Stanek and Alberto Veira Ramos

Centre for Social Studies/ University of Coimbra; University of Madrid

Sociological Research Online, 18 (4) 16

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/4/16.html>

10.5153/sro.3134

Received: 25 Jan 2012 Accepted: 26 Jun 2013 Published: 30 Nov 2013

Abstract

This article provides insight into the determinants of occupational mobility recorded for immigrants between their last job in the region of origin and their first job in Spain. Multinomial and bivariate logistic regression models are applied to identify the strongest predictors of upward and downward mobility when immigrants move from one country's labour market to another. This study's empirical analysis was carried out using data from the Spanish National Immigrant Survey of 2007. Our results show that ethnic segmentation in the Spanish labour market negatively affects the occupational mobility of immigrants. Secondly, we observe that non EU15 immigrants are at higher risk of downward mobility. Thirdly, higher levels of education offer protection against downward mobility and increase the chance for upgrading. Finally, contrary to our predictions, social capital embedded in support received from friends and relatives who reside in the destination country increases the risk of occupational downgrading and reduces the possibility of upward mobility.

Keywords: Migration Occupational Mobility, Spain, Labour Market Segmentation, Human Capital, Social Capital, Gender Gap

Introduction

1.1 In the late 1980s, in keeping with the general trend observed among Mediterranean countries, Spain became a destination for many economic immigrants. However, it was not until the end of the 1990s that the migratory waves increased substantially. Between 2000 and 2006 the average increase in the number of foreigners migrating to Spain was nearly 570,000 per year. As a result, foreigners currently represent over twelve percent of the country's total population (Cebolla & González-Ferrer 2013). This massive inflow of immigrants had a significant impact on the Spanish economy and on the structure of its labour market. It has been estimated that between 2000 and 2005 up to 50 percent of the growth in Spanish GDP was generated by immigrant workers and of the eight million new jobs created between 1994 and 2007, two and a half million were occupied by immigrant workers (Cachón 2009). Thus, immigrants played a crucial role in the rapid growth of the Spanish economy prior to the financial crisis of 2008.1.2 This boom in the immigrant population and the changing ethnic structure of the labour market has generated considerable interest among policy makers and social scientists. In recent years, various studies have sought to assess how foreign workers have fared in relation to Spanish workers with similar observable characteristics (Amuedo-Dorantes & De la Rica 2007; Bernardi et al. 2011). It has been observed that upon arrival, immigrants usually do worse than natives with similar socio-demographic characteristics and qualifications in terms of job stability, unemployment and occupational position (Cebolla & González-Ferrer 2008). In addition, the over-education gap between foreign and native workers tends to persist over time (Fernández & Ortega 2008). Alcobendas and Rodríguez-Planas (2009) showed that although immigrants begin to experience upward mobility within the first five years of residence in Spain, their occupational status never fully converges with that of Spaniards with comparable skills. Similarly, Izquierdo et al. (2009) observed that despite a significant reduction in the wage gap between foreign and native workers over the first five years of residence in Spain, the disparity does not disappear completely.

1.3 Although the patterns of post-migratory occupational adjustment seem to be fairly clear, there are other aspects of immigrant integration into the labour market that remain unknown. One such area is the phenomenon of occupational mobility that occurs when foreign workers move from their country of origin to a host country. Therefore the purpose of this article is to assess the occupational mobility patterns of immigrant workers in Spain. More specifically, we will try to establish the main determinants of occupational mobility among immigrant workers in the Spanish labour market by comparing the status of their last job in the country of origin to that of their first job in Spain. We use basic descriptive statistics and logistic regression models to examine the impact of several demographic, social and contextual factors on occupational mobility at migration and to test several hypotheses that are presented in the following section.

Empirical background and hypotheses

2.1 It was Chiswick (1977) who, in his seminal study on assimilation of immigrants in the United States, first observed that occupational mobility between the country of origin and the country of destination takes a U-shaped pattern: downward mobility in the first job after migration, followed by an improvement in occupational status after a period of time. This trend has also been observed in more recent studies showing that newly arrived immigrants are very likely to suffer occupational downgrading when they reach the destination country (Rooth & Ekberg 2006; Redstone Akresh 2008). In our study, however, due to data limitations[1], we focus on the first part of this occupational trajectory; that is to say, we observe occupational mobility between the last job in the country of origin and the first job attained upon arrival to Spain.2.2 Several studies have revealed that occupational mobility depends on an immigrant's individual qualities as well as contextual variables related to the characteristics of the labour market and the society in which they settle (Redstone Akresh 2006). With this in mind, we evaluate how occupational mobility upon migration is affected by gender, structural and institutional constraints, as well as individual characteristics such as human capital and social capital. In the following paragraphs we establish our hypotheses for each of these sets of determinants of occupational mobility.

Gender

2.3 Cross-sectional studies in different geographical contexts revealed that among immigrants women experience a greater occupational setback than men after moving to a foreign country (Raijman & Semyonov 1997; Powers & Seltzer 1998). It has been observed that the upward occupational mobility of women is also impeded by structural restrictions within labour markets. More specifically, gender segmentation relegates the female immigrant population to a narrow range of jobs, some of which have very limited possibilities for upward mobility given the type of demand and the organisation of the work (for example, domestic work), or because they require a heavy investment in human capital (Del Río & Alonso-Villar 2010). In addition, some authors suggest that the traditional division of productive and reproductive roles in households makes it more difficult for the female population to achieve vertical mobility or to maintain their occupational status upon migration; not only do women have to reconcile their economic activity with housework, but they also have limited access to the resources needed to improve their occupational status, such as social networks (Cobb-Clark et al. 2005). Hence we expect that, as occurs in other receiving countries, immigrant women in Spain will be at greater risk of suffering downward occupational mobility than men (hypothesis H1a) and have a lower probability of experiencing upward mobility (hypothesis H1b) when migrating.

Institutional factors

2.4 Institutional factors and, more specifically, migration policies should be taken into account when analysing how newly arrived immigrants locate themselves in the Spanish occupational structure. During the observation period covered by our study, nationals of the old European Union member states (EU15) enjoyed the same rights and conditions as Spanish workers in terms of mobility within EU boundaries and work opportunities. Free movement of the labour force includes the right to seek employment in another member country, to move there to search for employment, to reside there for the purpose of employment, and to remain there following the completion of employment. This contrasts with the severe restrictions faced by immigrants from non-EU15 countries, including those from the new accession member states (EU10)[2]. Over the last two decades, Spanish authorities have implemented policies in order to organise immigration flows so that they would both meet the needs of the labour market and at the same time protect native workers (Ferrero-Turrión & López-Sala 2009). Immigrants must follow a complex bureaucratic procedure and find occupations that cannot be filled by Spanish unemployed in order to obtain their first work permits. Initial work permits are valid only for a specific economic sector and territory. Restrictive migratory policies coupled with strong demand for foreign workers within the Spanish economy and lax control of the internal labour market resulted in an increasing number of irregular immigrants being employed in the shadow economy during the initial years of their stay in Spain (Cebolla & González-Ferrer 2008). Most of the non-EU15 immigrants entered Spain irregularly – or remained in the country without a valid permit after entering with a short-term visa and later received legal status through regularisation programmes (Bernardi et al. 2011; Sabater & Domingo 2012). Furthermore, during the reference period of our analysis institutional constraints channeled non-EU15 immigrants through low-prestige and low-wage occupations in the secondary labour market (Cachón 2009; Stanek 2011). Therefore, in our analysis we expect immigrants from outside the EU15 to have higher risks of occupational downgrading upon migration (H2a) and lower probabilities of improving their occupational situation (H2b) compared to immigrants from the EU15 countries.

Structural factors

2.5 Another factor that affects occupational mobility in Spain is its segmented labour market (Polavieja 2003). Segmentation theory argues that the labour market is divided into at least two different segments, each with its own structure, allocation rules and occupational mobility mechanisms. The core/primary segment offers jobs with relatively high wages, acceptable working conditions and possibilities of occupational promotion, whereas jobs in the periphery/secondary segment are low paid, unstable, menial, labour-intensive and with little room for occupational mobility (Piore 1979). These features make it difficult for employers to attract native workers to secondary segment jobs and create continuous demand in advanced economies for workers from less industrialised countries. Immigrants tend to be channelled into low paid jobs in specific labour intensive economic sectors regardless of their skill level and previous work experience. This explains why, as a general pattern, most immigrants suffer occupational downgrading at migration (Pedace 2006).

2.6 The history of economic transformations that have been taking place for last few decades in Spain suggest that labour market segmentation is a factor that has greatly conditioned labour force mobility in Spain (Alba et al. 2007). Since 1990 a significant share of wealth has been generated by labour intensive sectors such as hospitality services, construction and agriculture (Garrido et al. 2010). Expansion of these branches of the economy has resulted in a considerable increase in the demand for low-skilled manual workers. Simultaneously, educational expansion has improved the occupational positions held by Spanish workers (especially in specific categories such as women and skilled young adults). By extension, this left many low-skill jobs vacant (Domingo et al. 2007). These transformations have concentrated and clustered immigrants in the lowest positions of the least appealing economic sectors of the Spanish economy (Cachón 2009). Three out of every four foreign workers are employed in jobs requiring a low-skill level and three out of every five immigrants work in agriculture, hospitality and domestic services, commerce or construction (Veira et al. 2011). Considering that the need to fill the lower positions in the labour market is one of the key factors driving the occupational distribution of immigrants in Spain, we hypothesise that immigrants who find their first job in Spain in economic sectors which constitute ethnic niches for foreign workers (namely agriculture, construction, hospitality and domestic work) are more likely to suffer downward mobility upon migration (H3a) and less likely to experience upward mobility (H3b). We also expect that immigrants who arrived in Spain during the period of major economic expansion (2002–2007) are at higher risk of experiencing an occupational downgrade (H4a) and less likely to improve their occupational status (H4b).

Human capital

2.7 From the human capital perspective, occupational mobility varies in relation to individual productivity that should be highly dependent on education, professional training and experience. According to this idea, higher education and occupational status at the country of origin should favour immigrants' integration into the labour market of the destination country. However, existing relevant literature on this topic argues that human capital is often country-specific and not perfectly portable or transferable to the host country's labour market (Friedberg 2000; Gathmann 2010). With respect to formal education it is argued that some certificates and licences obtained in developing nations may be difficult to validate in a first-world country because of bureaucratic impediments[3] (Redstone Akresh 2006; Reyneri & Fullin 2011). Similarly, occupational skills and experience obtained in less technologically advanced countries are rarely transferable to more developed economies (Chiswick et al. 2003). In fact it has been observed that immigrants who occupied highly skilled occupational positions in their countries of origin face a greater risk of downward mobility as they are more likely to find that some of their professional skills are of less value in the destination country (Chiswick et al. 2005). Another reason to expect a limited return on human capital after migration is the immigrant's poor knowledge of the recruitment channels and the general functioning of the host country's labour market institutions. This often forces immigrants to accept jobs below their formal qualifications and professional experience (Reyneri & Fullin 2011).

2.8 As argued above, the effect of human capital on occupational mobility at migration is very complex. However here we presume a positive effect of education but no returns on previous occupational experience. Regarding education effect, substantial and widespread empirical evidence confirm that higher educational level has a significant and positive association with obtaining higher ranked occupations after arrival (McAllister 1995; Raijman & Semyonov 1995; Redstone Akresh 2006). This relation is usually explained by the fact that employers value education because they enhance employee productivity (Fuller & Martin 2012). Additionally, previous research has shown that in Spain, lower education is strongly linked to a higher risk of working in immigrant occupational niches, and working in immigrant niches is related to a higher risk of occupational downgrading (Veira et al. 2011). Concerning the effect of occupational position before migration, we concur with the findings referred to in the previous paragraph which hold that migration generally implies a devaluation of job specific human capital, thus, paving the way for downward mobility. Therefore, we assume that immigrant workers with higher educational level are less likely to suffer occupational downgrading (H5a) and more likely to experience upgrading (H5b). However, immigrants with a higher occupational profile in their country of origin are expected to suffer a greater risk of downward mobility (H6a) and less likely to experience upward mobility (H6b).

2.9 Finally, language proficiency is generally seen as one of the most important dimensions of human capital for newly arrived immigrants. Chiswick and other researchers have stressed the importance of being able to communicate in the host country's language in order to facilitate transferring skills from the country of origin to the host labour market (Chiswick et al. 2003; Rooth & Ekberg 2006). Thus, Spanish language proficiency (in our case) should be considered a key factor that prevents or mitigates against occupational downgrading when immigrants enter into the labour market, as it makes it easier for immigrants to adjust the skills acquired in their country of origin to the new context. We therefore expect that Spanish speaking workers from Latin America would be less prone to suffer downward mobility (H7a) and more likely to improve their occupational position at migration than other non-EU15 immigrant groups (H7b).

Social capital

2.10 Our analysis also takes into account the social capital of immigrants derived from personal contacts at arrival. Social capital is usually defined as the ability of individuals and groups to secure specific resources through membership of interpersonal networks and social institutions (Portes 1998). Social capital can be converted into information, referrals (to accommodation, for example) or direct financial help, which reduces the costs of migration and adaptation into the host society and labour market (Espinosa & Massey 1999; Gurak & Caces 1992). The role of social capital in the job market has been widely developed in the sociological literature, but empirical evidence about its impact on the occupational attainments of immigrants is still unclear. On the one hand, a number of studies suggest that having friends and relatives with migratory experience improves the efficiency and effectiveness of an immigrant's job search because they provide more accurate information on employment opportunities, hiring practices and labour-market conditions in the host country (Nee & Sanders 2001; Aguilera & Massey 2003). In addition, it has been claimed that this kind of social capital is particularly useful immediately after arrival, when the immigrant lacks other social resources, as friends and relatives filter job opportunities and reserve better ones for members of their own social networks (Mullan 1989; Pascual et al. 2007).

2.11 Conversely, some scholars have highlighted the detrimental effect of using networks of relatives and friends for job-seeking (Portes & Sensenbrenner 1993; Portes 1998; Nannestad et al. 2008). Newcomers usually depend strongly on social resources within family structure or ethnic collectives where the same information is being circulated, and these sources therefore may provide limited information on labour market opportunities (Lancee 2010). Dependence on ethnically or socially homogenous networks may channel newly arrived immigrants into jobs (mainly in the ethnic niches), which are characterised by low status, low wages and poor working conditions (Nee & Sanders 2001; Kazemipur 2006). Therefore, some researchers suggest that social networks provide a temporary shelter against unemployment for newcomers, but the trade-off is a high risk of occupational downgrading (Kalter & Kogan 2011).

2.12 Given the absence of clear empirical evidence on the effects of social capital on labour market attainments for newly arrived immigrants, our expectations for immigrants who rely on friends and relatives to find their first job are ambivalent (H8a for downward mobility and H8b for upward mobility). However, we argue that having a contract (verbal or formal) with a Spanish employer before migration will reduce the risk of losing occupational status (H9a) and increase the possibility of upward mobility (H9b).

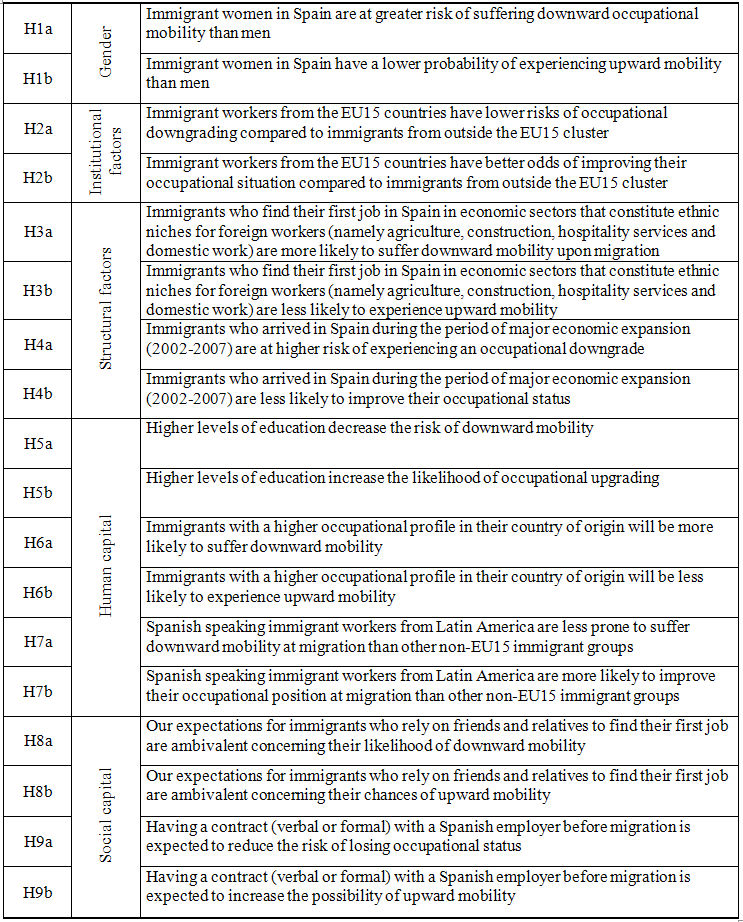

| Table 1: Hypotheses concerning occupational mobility upon migration to Spain |

|

Data and methods

3.1 The analyses presented in this article rely on the National Immigrant Survey (NIS-2007) data set conducted by the Spanish National Statistics Institute. Data were collected between November 2006 and February 2007 from a population sample of 15,465 people over 15 years old who were born abroad. The survey collected information on personal characteristics such as gender, age, level of education, country of origin and year of arrival. It also collected data on their occupational backgrounds in the country of origin and on the first job attained in Spain, enabling us to assess whether immigrants experienced occupational mobility when moving to Spain.3.2 For the sake of analytical consistency, we reduced the original NIS-2007 sample to 3,506 individuals. We selected only immigrants who reported the occupation and branch of industry of the last job they held before migrating, and the first job they attained in Spain. The population analysed was limited to those arriving from four main regions, which represent 90.5 percent of the whole NIS-2007 sample. The first category is composed of immigrants from the pre-2004 enlargement European Union countries (EU15). The second category includes individuals from the new accession European Union member states (EU10). The third includes immigrants from Maghreb countries; and the fourth, immigrants from Latin America. There were too few cases from Sub-Saharian Africa and Asia to consider them as separate regions. We also limited the sample to those who arrived between 1985 and 2007 (although more than 85 percent arrived after 1996 and almost 60 percent after 2001)[4]. Furthermore we focused on immigrants who were already fully economically active at the time of migration that is 25 to 55 years old at the moment of their arrival. Another restriction was to consider only workers who completed their schooling before migrating. Finally we also excluded individuals who continued to work for the same employer after migrating (i.e. those posted to Spain as a new work destination).

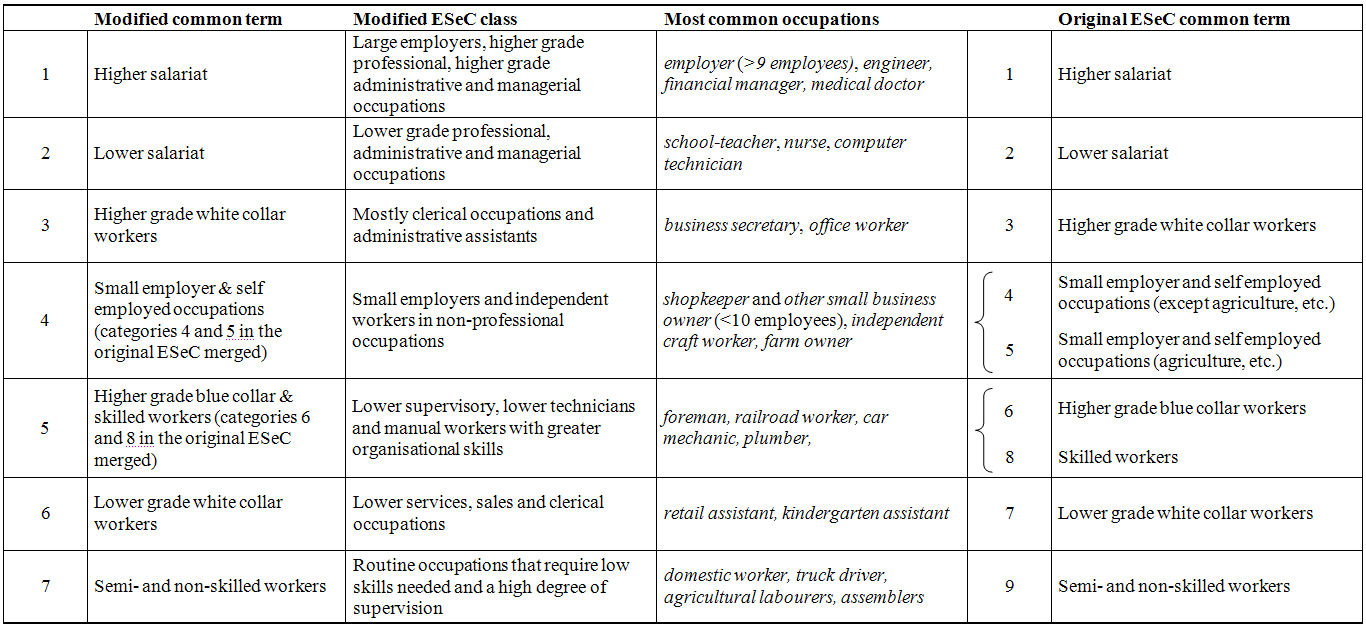

3.3 Our dependent variable, 'Occupational mobility', was created using two other variables containing information on the last occupation immigrants had in their country of origin and the first occupation they found after their arrival to Spain. To classify workers in comparable categories we employed the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC schema). The ESeC schema was established to operationalise socio-economic positions with official micro-data based on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88)[5]. Therefore it is particularly useful in cases of cross-country studies (Rose & Harrison 2007). The ESeC is based on theoretical assumptions derived from the Erikson–Goldthorpe–Portocarero (EGP) class-scheme (Erikson & Goldthorpe 1992) in which socio-economic positions are defined by the nature of employment relations. Employment relations in the ESeC are defined considering two main dimensions: the level of human asset specificity[6] a given job requires from the worker and how difficult it is for the employer to monitor the tasks performed by the worker. Before conducting our analyses, the ESeC schema was reordered according to the mean earnings of each occupational category in order adapt it to the peculiarities of the Spanish labour market. Because immigrants employed in lower technical occupations have higher average salaries than those employed in lower services, sales and clerical occupations, we changed their positions on our ranking scale. In addition, as the number of self-employed immigrants in agriculture was very small we merged this category with that of small employers and self-employed workers in non-agricultural economic sectors. Table 2 provides a detailed view of the modifications to the ESeC classification, as well as a description of each occupational category.

3.4 The independent variables are 'Age at arrival in Spain', 'Gender', 'Region of Origin', 'Period of arrival in Spain', 'Industrial sector of the first job in Spain', 'Contract upon arrival', 'Job search aided by friends and relatives', 'Level of education' and 'ESeC occupational category in the country of origin'. Age at arrival is a metric variable ranging from 25 to 55. Variables such as 'Period of arrival' and 'Industrial sector of the first job in Spain' measure the effect of structural and contextual constraints, while the education and occupational categories account for the effect of individual characteristics related to human capital. 'Contract at arrival' is a dichotomous variable distinguishing between those who had a contract (written or verbal) with a Spanish employer before they arrived in Spain. 'Job search aided by friends and relatives' indicates whether or not immigrants obtained their first job in Spain through the assistance of friends or relatives who were already residing in Spain.

3.5 Our next step was to divide our sample into two sub-samples, distinguishing immigrants who had semi- and non-skilled occupations in their country of origin (1,039 cases) from the rest (2,467 individuals). In the case of those who were employed in other occupations before they moved to Spain we sought to identify which variables are most strongly associated with either upward or downward occupational mobility[7]. However, for those who had semi- and non-skilled occupations in their countries of origin and therefore could not experience downward mobility, our aim was to identify which variables significantly increased the likelihood of upward mobility.

| Table 2: Description of the modified European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) |

|

3.6 To analyse the determinants of occupational mobility experienced by immigrants who were employed in other than semi and non-skilled occupations before migrating we implemented a multinomial logistic regression with 'no mobility' as a category of reference. In the case of those who were employed in semi- and non-skilled occupations in their country of origin we applied a binomial logistic regression, since this category of workers has no room for downward mobility. In addition to the complete models which include all variables, we have implemented reduced models in order to identify the relative impact of three groups of variables: variables reflecting the structural and institutional factors, variables related to human capital and variables accounting for the effect of social capital.

Descriptive analysis

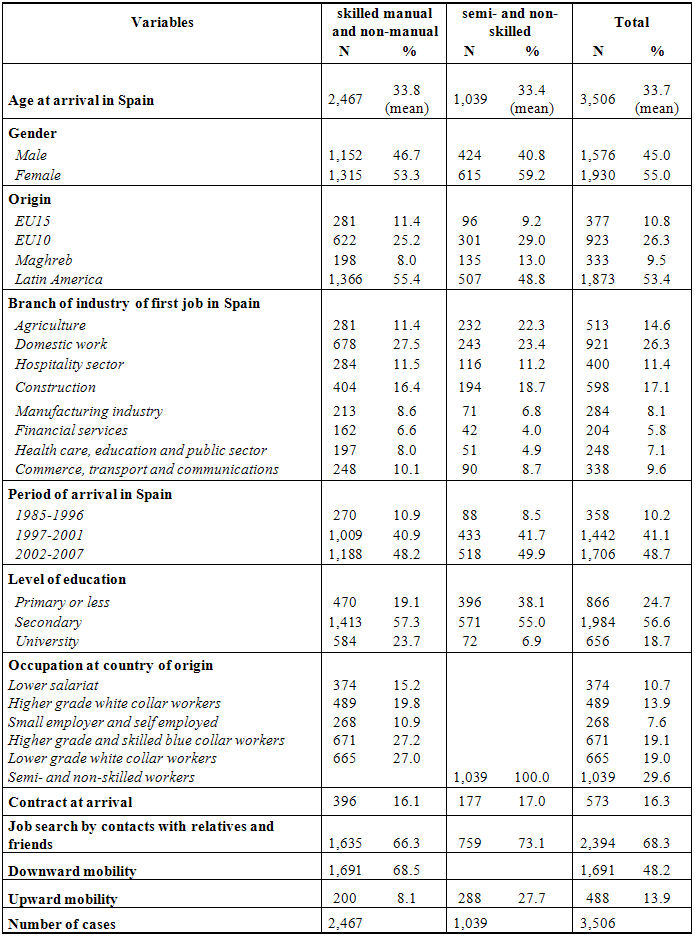

4.1 Table 3 describes some of the relevant characteristics of the whole sample and the two subsamples employed in our study. The data reveal that the proportion of women is slightly higher than that of men and the average age at arrival was 33.7. Over 53 percent of workers migrated from Latin America, 26.3 percent from the EU10 countries, 10.8 percent from EU15 countries and 9.5 percent from the Maghreb region of North Africa, mainly Morocco. Over 88 percent arrived in Spain between 1997 and 2007. Sample data confirms that after arrival immigrants tend to join a limited number of specific economic sectors. The branches of the economy in which most immigrants found their first job are domestic work (26.3 percent), construction (17.1 percent) and agriculture (14.6 percent), followed by hospitality (11.4 percent). In contrast, only 14.9 percent found their first job in finance, health care or education.4.2 When occupational status prior to migration is taken into account, as much as 29.6 percent of immigrants were employed as semi- and non-skilled workers in their country of origin. Another 19.1 percent were occupied as higher grade blue collar and skilled workers, and 19.0 percent worked in low grade white collar jobs. In all, 65.8 percent of immigrants were employed in their countries of origin in occupations that, in terms of the modified ESeC classification scale, require low levels of human asset specificity and are easily monitored by employers. In terms of education, only 18.7 percent of immigrants have a university degree and 56.6 percent completed secondary education. Regarding social capital it must be noted that 83.7 percent arrived in Spain with no formal or informal (verbal) contract. However, at least 68.3 percent relied on their friends and relatives to find their first job after arriving in Spain.

| Table 3: Descriptive statistics of the sampled population's main characteristics |

|

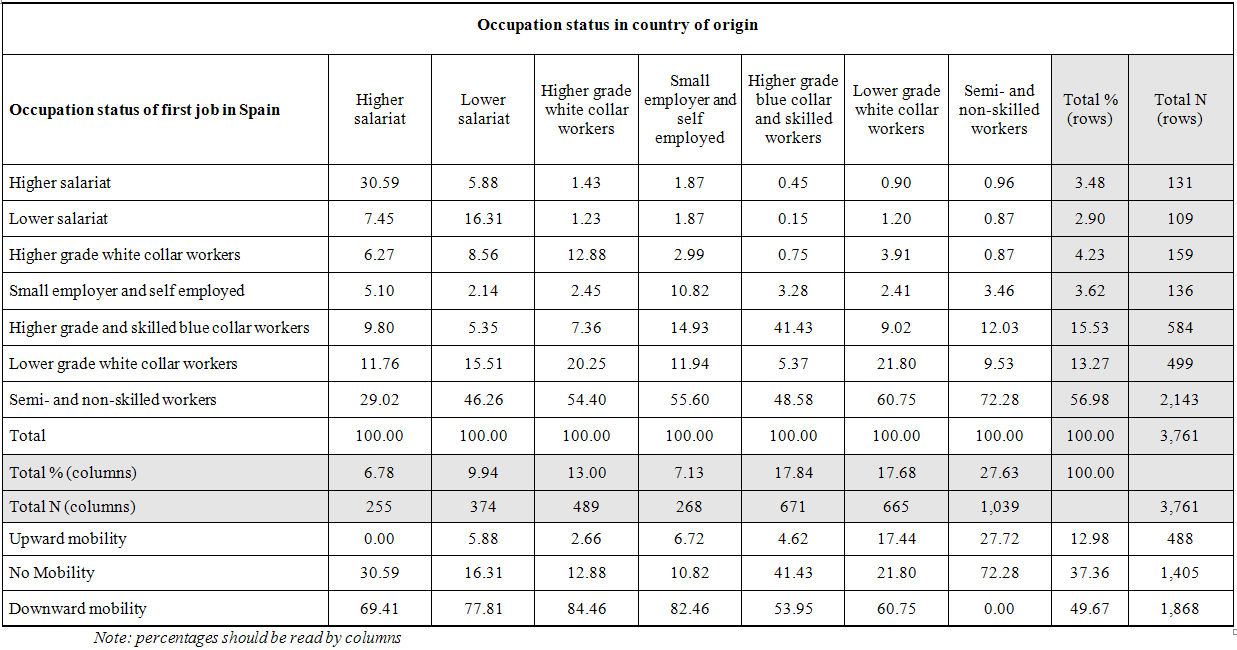

| Table 4: Occupational change from last pre-immigration to first post-immigration job (%) |

|

4.3 Table 4 records occupational mobility experienced by immigrants between the last job held before migration and the first job obtained in Spain. After their arrival in Spain, 49.67 percent experienced downward occupational mobility, less than 12.98 percent upward mobility and 37.36 percent found jobs adequate to their pre-migration occupational status. Another indicator demonstrating that downward mobility is the dominant trend is that although only 27.63 percent of immigrants were employed in semi- and non-skilled occupations in their country of origin, nearly 56.98 percent took up these types of jobs in their first posts in Spain. It is noteworthy that the category of immigrants with the lowest rate of downward mobility is found among those who were skilled blue collar workers in their countries of origin (53.95 percent). Additionally those employed in the lowest occupational categories at origin have the highest rates of upward mobility (17.44 and 27.72 percent respectively). The remaining categories of immigrant workers suffer rates of downward mobility that are higher than 60 percent. The nature of this transition is dominated by mobility from a white collar or a skilled blue collar occupation into the position of a semi or unskilled worker, the lowest occupational category (60.75 percent of lower grade white collar employees move into unskilled occupations and about 50 percent among the remaining categories). The only exception to this general trend is those who belonged to the higher salariat in their countries of origin. These immigrants suffer downward mobility mainly by moving into other white collar occupations, although 29.02 percent become employed as unskilled labour after arriving in Spain. Finally, it should be noted that only immigrants with the lowest occupational status in their country of origin have significant chances to improve their positions after migrating to Spain.

Multivariate analyses

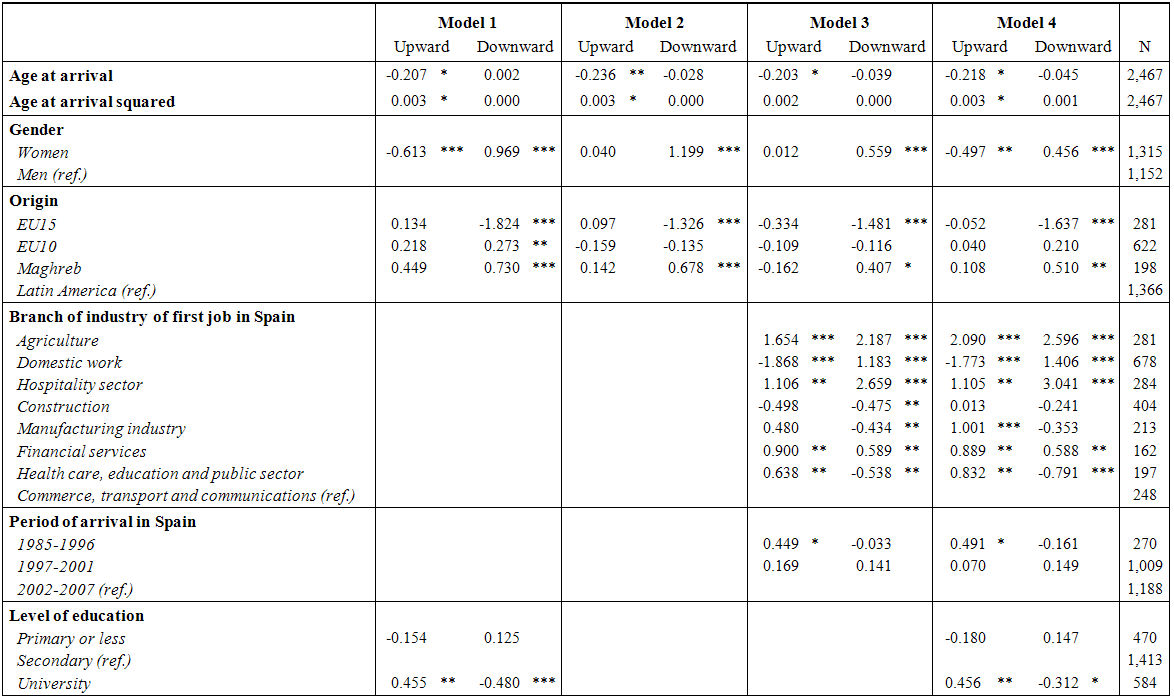

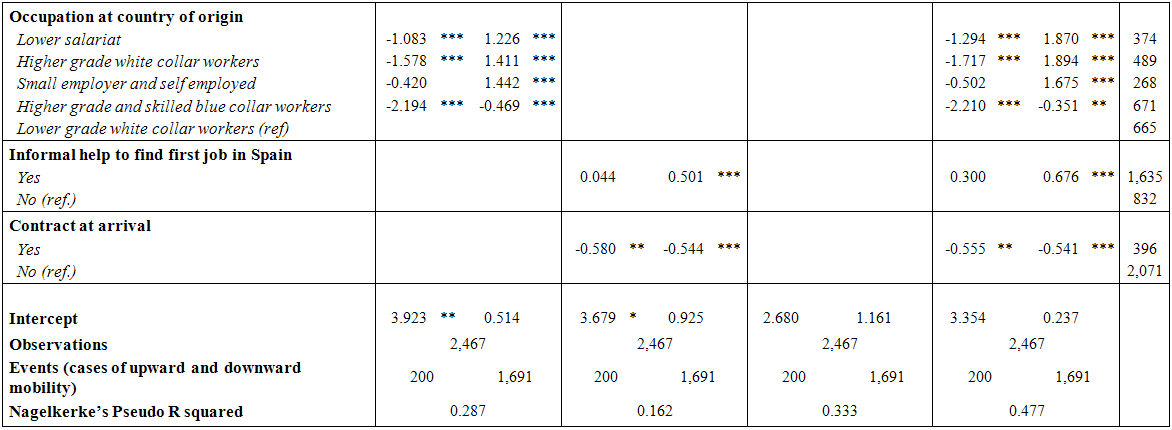

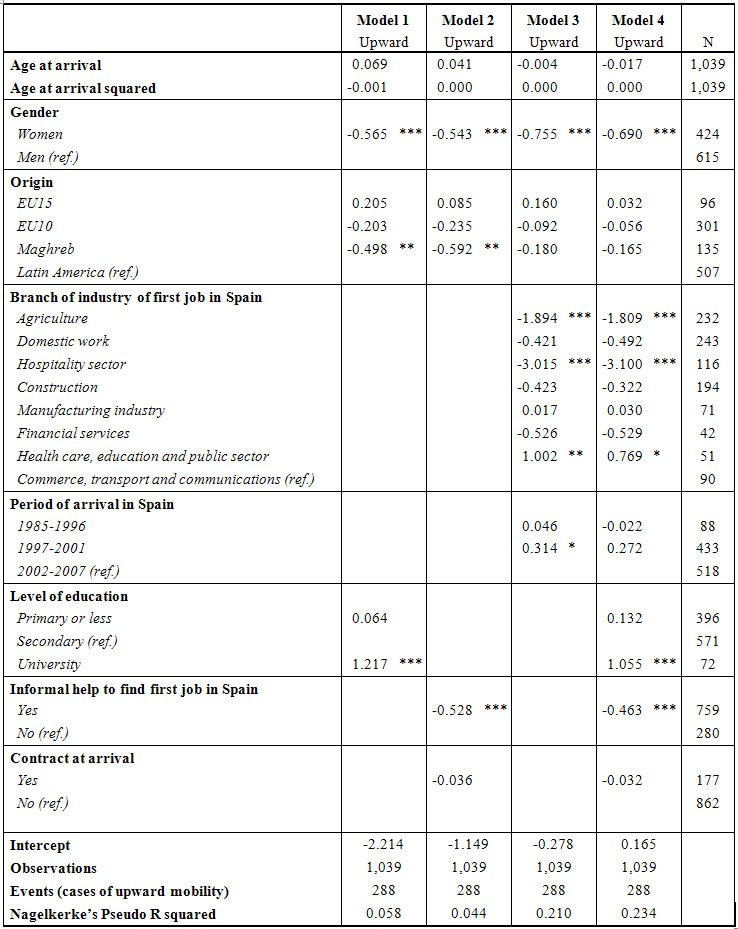

5.1 This section addresses the questions and hypotheses presented above. The responses are based on the results of our statistical models carried out for the two subsamples of immigrant workers we designed. Findings are presented as follows: first, we report our findings concerning the gender gap; then we describe how the structural and institutional variables operate; next, we discuss the effects of variables related to human capital; finally, we assess the impact of the variables associated with social capital.Gender

5.2 The results corroborate our hypotheses concerning the existence of a gender gap (H1a and H1b). Women are at higher risk of experiencing downward mobility and are less likely to experience upward mobility than men. It must be noted that the results for upward mobility among workers in skilled manual and non-manual occupations (Table 5) show that the gender gap effect seems to fade away (coefficients for female are not statistically significant) in the second and third model (those models which do not account for the effects of education and occupation in the country of origin). However, the full model (M4) for upward mobility among workers in skilled manual and non-manual occupations and all models for upward mobility among workers in semi- and non-skilled workers occupations show clear evidence of the existence of inequalities between men and women.

Institutional factors

5.3 Coefficients shown in Table 5 for immigrants who were workers in skilled manual and non-manual occupations before migration clearly indicate that EU15 immigrants suffer lower risks of downward mobility than those from other parts of the world. This result is in line with the hypothesis H2a which argues that a more favourable legal context helps workers from other EU15 countries retain their occupational status, since non EU15 immigrants face significant legal obstacles to their full incorporation into the regular labour market. This legal barrier greatly restricts the access of non-EU15 workers to jobs other than low-skill and low positions in the secondary labour market or in the shadow economy, increasing the odds that they will experience downward mobility. Regarding upward mobility, however, there are no clear signs that workers from EU15 countries have greater chances than non-EU15 workers (hypothesis H2b). In other words, Spain does not offer newly arrived, low-skilled foreign workers much possibility of occupational promotion, whatever their origin or legal status. The results for immigrants who worked in semi- and non-skilled occupations in their country of origin, shown in Table 6, do not indicate that immigrants arriving from the EU15 are more likely to experience upward mobility. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that this result is due to the fact that our sample only contained a small number of semi- and non-skilled workers coming from the EU15.

5.4 Assessing the existence of inequalities among non-EU15 immigrants, we observed that those from the Maghreb region are most likely to suffer downward mobility. At first glance, they also seem to have fewer opportunities for upward mobility, but this effect is no longer significant after controlling for the industrial sector, suggesting that semi- and non-skilled workers from the Maghreb tend to concentrate in sectors offering fewer chances for upward mobility.

Structural factors

5.5 Our results presented in Table 5 and Table 6 confirm that occupational mobility is clearly dependent on the sector of the economy in which immigrants attain their first job in Spain. As expected in hypotheses H3a, economic sectors in which immigrant labour tends to concentrate such as domestic work, agriculture or hospitality are more likely to penalise recently arrived immigrants with downward mobility. However, this does not apply to the construction sector, which is one of the four main economic activities where immigrant labour concentrates in Spain (Stanek & Veira 2012). This sector seems to be, along with the manufacturing industry, a friendlier environment for foreign workers in terms of occupational mobility.

5.6 Outcomes for upward mobility (H3b) are mostly but not entirely in line with our expectations. Immigrants who worked in semi- and non-skilled occupations prior to migration and enter into the economic sectors in which immigrant labour tends to concentrate are least likely to achieve upward mobility. This is also the case for skilled manual and non-manual employees who become domestic workers in Spain. However, among those who were skilled manual and non-manual workers before migration and enter into the agriculture and hospitality sectors the chances of achieving upward mobility is greater than for the remaining categories. These results indicate that immigrants who have prior working experience in skilled manual and non-manual jobs have greater chances of being valued in these two economic sectors than in other areas. Nonetheless, it must be emphasised that the likelihood of suffering occupational downgrading when entering these economic sectors is much higher than the odds of experiencing upward mobility.

5.7 The period of arrival was not found to play a major role (H4a and H4b). Some evidence indicates that those who arrived most recently fare worse in terms of occupational mobility, but the available data show a limited level of statistical significance.

| Table 5: Results of multinomial regression on occupational mobility for skilled manual and non-manual workers at origin (Reference category is 'no mobility') |

|

| Table 6: Results of binomial regression on occupational mobility for semi- and non-skilled workers at origin (Reference category is 'no mobility') |

|

Human capital

5.8 Our expectations on the effect of level of education (hypothesis H5a and H5b) were confirmed by the results. Although no significant differences between those with secondary and those with primary education were observed, immigrants with university education are less likely to suffer downward mobility and more likely to move upwards in comparison to immigrants with less education. Regarding the effect of the last occupation held in the country of origin (hypotheses H6a and H6b), Table 5 shows that immigrants who were lower grade white collar workers in their country of origin are the most likely to experience upward mobility after migration, and the second least likely to suffer downward mobility (after the skilled blue collar workers). Thus, our hypotheses are generally validated with the exception of the higher grade skilled blue collar workers who are the least likely to experience occupational mobility in either direction. We believe these results indicate that immigrants employed as skilled blue collar workers in their country of origin are the most likely to find jobs in Spain that are at the level of their pre-migration occupational experience.

5.9 As for our hypotheses H7a and H7b concerning proficiency in the Spanish language, we have not found significant differences between EU10 and Latin American immigrants in the likelihood of experiencing occupational mobility, even after controlling for the branch of economy of first job in Spain. This clearly suggests that proficiency in Spanish does not offer a competitive advantage for Latin Americans in the Spanish labour market. We would argue that this may be because a large number of the jobs attained by immigrants in Spain do not require a high level of Spanish.

Social capital

5.10 Results clearly indicate that relying on help from friends and relatives to find the first job in Spain increases the risk of downward mobility and decreases the odds of upward mobility. We presume, therefore, that depending on friends and relatives may represent more of a constraint than an additional resource. Even though social networks offer relatively fast and secure access to jobs after migrating, they also may discourage immigrants from undertaking other, more efficient (in the long run) strategies to search for a job. Finally, our predictions regarding the importance of establishing a relationship with a Spanish employer before arrival, proposed in the hypotheses H9a and H9b, were fully confirmed. Results show that having a contract with a Spanish employer before migrating significantly decreases the likelihood of both upward and downward mobility.

Explanatory performance of models

5.11 With regard to the relative impact of structural and contextual variables versus individual characteristics such as human and social capital, a comparison between our three reduced models indicates that the highest explained variance is provided by the model that captures the effect of the economic sector where first employment was found (33.3 percent in the multinomial analysis and 21 percent in the binomial analysis). We also observe that variables related to human capital seem to be more important than social capital resources in terms of finding a first job in Spain without suffering occupational downgrading.

Discussion

6.1 This paper contributes to the existing literature on occupational mobility of immigrant workers in two ways. Firstly, it confirms that Spain is no exception to the general rule that the dominant trend among immigrant workers is to suffer downward occupational mobility after their arrival to a new country. In this respect our findings are consistent with results of other studies carried out in other countries (McAllister 1995; Seifert 1997; Chiswick et al. 2005; 2006). Secondly, we provide empirical evidence on the long-standing debate between the two main (and often competing) theories that seek to explain the mechanisms behind the occupational downgrading suffered by most immigrant workers worldwide. One explanation emphasises the role played by the individual resources of immigrants and their capacities to adapt to the demands of the host labour market while another focuses on the structural conditions of the receiving labour market (Constant & Massey 2005).6.2 The former perspective explains the initial disadvantage of immigrants as a result of the mismatch between individual assets (educational level, skills and experience, proficiency in the language of the host country, etc.) and the specific demands of the host labour market (Pozzolo 1999). From this point of view, occupational downgrading at migration is mainly due to the lack of availability of employable skills in the host country labour market, often caused by the low international transferability of immigrant's human capital. The second perspective assumes that the integration of immigrants is not necessarily related to their individual characteristics but results from the inherent segmentation of the labour market in advanced industrial economies (Sassen 2001). From this point of view, native workers in most affluent societies refuse to seek employment in the less prestigious occupations of the non-core secondary sector associated with labour-intensive activities, low-skill requirements and low pay, and therefore create a strong demand for foreign labour. This demand is especially intense when the economy expands and better positions become more widely available to autochthonous workers. Under such contexts new immigrants tend to be channelled into the secondary sector (McGovern 2007).

6.3 Our study shows that in Spain occupational mobility is mainly (though not exclusively) conditioned by the structural characteristics of the labour market. The comparison between different statistical models showed that structural determinants seem to play the most important role in shaping newcomers' occupational trajectories. Furthermore, we observed that immigrants who find employment in the labour-intensive branches of economic activity such as agriculture, hospitality and domestic labour are more likely to suffer occupational downgrading. We also saw that occupational upgrading is far more frequent among immigrants who worked in semi- and non-skilled occupations in their countries of origin (27.7 percent), than among those who were more skilled (8.1 percent), indicating that the Spanish labour market is indeed more attractive to low-skilled immigrant workers than to highly trained professionals. Indeed, immigrants who are the least likely to experience downward mobility are those who find jobs in the manufacturing and construction sectors. It must be stressed that the significant role played by structural factors in Spain may be due to the fact that, as a typically Southern European economy, it is strongly biased towards low productivity sectors with a huge demand for elementary occupations. Therefore, these results may not be valid for other countries where labour markets are more biased towards high skilled jobs such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Denmark (Reyneri & Fullin 2011).

6.4 Variables related to individual characteristics are found to play a secondary but still significant role as determinants of occupational mobility in migration to Spain. The Spanish Language proficiency of Latin American immigrants, holding a university diploma and having employment experience as a lower technician at the country of origin are attributes that contribute to mitigate the effects of the labour market segmentation and help immigrants to retain their occupational status and even to improve it. It is important to stress that according to our results fluency in the Spanish language does not help Latin Americans with respect to EU15 workers but it does provide them with a small advantage with respect to the other non-EU15 workers. The relative good performance in terms of finding an adequate job match of immigrants with a background as higher grade and skilled blue collar workers should be interpreted as a consequence of the high demand for this kind of labour in Spain during the decades prior to the current economic crisis. Immigrants with technical skills filled a crucial gap in the Spanish economy given that the educational system did not provide adequate vocational training in the numbers required, particularly in the construction and manufacturing sectors. Therefore weaknesses in the Spanish educational system may be behind the easier transferability of skills of lower technicians during booms in the economy.

6.5 We also found several additional factors that overlap the previously mentioned determinants and whose main effect is to reinforce the consequences of the typically southern European labour market segmentation. At the institutional level we found evidence that European regulation securing free movement of labour within EU15 countries protects EU15 nationals from downward mobility while nationals from third countries, including those from the new accession member states (EU10), face significant obstacles to retain their occupational position. Results show clearly that non-EU15 workers suffer a higher risk of downward mobility than immigrants from EU15 countries. Another factor that clearly determines downward and upward mobility among immigrants to Spain is gender. Immigrant women find themselves in a labour market where the occupational structure is still to a great extent segmented by gender. Thus, they are doubly disadvantaged: as immigrants and as women. Finally, there is no evidence to suggest that social capital helps immigrants against the negative consequences of the already existing segmentation of the Spanish labour market. The capacity of the immigrant's networks to provide valuable information on job opportunities seems to be rather limited. Our results demonstrate that immigrants who rely on information from relatives and friends when seeking a first job in Spain actually increase their risk of socioeconomic downgrading and block their chances of upward mobility. In this sense, our research refutes those studies which suggest that immigrants who lack social network support in destination countries were more likely to move into less desirable, low skilled and low paid jobs (Nee & Sanders 2001). One possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that immigration to Spain is a recent phenomenon and thus new immigrants cannot rely on strong pre-existing ethnic networks that might facilitate their access to skilled occupations, as their resources are still relatively poor.

Limitations

7.1 The NIS-2007 provides the most comprehensive data source on social, demographic and economic characteristics of immigrants residing in Spain. Nevertheless, it has some limitations. Firstly, due to the specificity of the data on occupation we were not able to construct occupational attainment as a metric variable, according to the categorisation of the International Socio Economic Index (ISEI scale), which has been used in several analyses of immigrants' occupational mobility in other countries[8] (Mulder & van Ham 2005; Redstone Akresh 2008). Secondly, our analysis only includes the occupational mobility of immigrants when transferred from the country of origin to Spain and does not cover further occupational trajectories. Our decision to focus on the first phase of the occupational trajectories of immigrants was motivated by the fact that massive migration to Spain is a relatively recent phenomenon. Thus, the available statistical data only covers short periods of time, which significantly restricts the in-depth analysis of occupational mobility. Finally, the National Immigrant Survey was conducted in 2007 and therefore does not cover the occupational situation of immigrant workers after the outbreak of the recent economic crisis of 2008. The crisis has caused massive job destruction, particularly among the immigrant population, provoking a considerable slowdown in the growth of the number of immigrants in Spain and a significant change in the social and demographic characteristics of newcomers (Cebolla & González-Ferrer 2013).Notes

1The analysis of the second part of Chiswick's 'U' curve of immigrant occupational trajectory is to some extent problematic because mass migration to Spain started after 2001, and by 2007 (when the National Immigrants Survey was carried out), a very large proportion of interviewees were still employed in their first job.2After the European Union enlargements in 2004 and 2007, the great majority of the EU15 countries (except the United Kingdom, Ireland and Sweden) restricted access of the new member countries' nationals to their labour markets during the transitional period (up to seven years). However, in May 2006, the Spanish government suspended this moratorium with regard to workers from the countries of the 2004 enlargement (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia) and in 2009, with regard to workers from Romania and Bulgaria. Taking into account the very short period of time elapsed since the opening of the Spanish labour market for workers from the 2004 enlargement countries (2006) until the moment the National Immigrants Survey was conducted (2007) we decided to include the new accession countries nationals in a separate category along with Bulgarian and Romanian workers, who were granted full access two years after the completion of the survey. Therefore, in our analyses we introduce two categories of EU migrants: old member states EU nationals (EU15), which includes migrants from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom, and 2004 and 2007 Central and Eastern European accession countries (EU10) which includes nationals of Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

3For instance, Raijman and Semyonov (1995) found that some educational diplomas such as those of engineers and technicians, are more transferable than others that are more locally-specific (e.g. lawyers).

4The period covered begins in 1985 because the mid 1980s marked the beginning of the economic migration to Spain (Arango 2004; Cachón 2009). The second dummy (1997–2001) reflects a period of economic recovery that culminated in a period of intense economic expansion at the beginning of the 21st century (2002–2007) marked by the creation of millions of new jobs (Garrido et al. 2010; Carballo-Cruz 2011).

5International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) is a classification for organising information on occupations elaborated by the International Labour Organization. It aims at harmonising the data from different countries for comparative purposes.

6Human asset specificity involves high amounts of job or organisation specific skills and knowledge and/or high investments by the employer in employee's work competences (Rose & Harrison 2007).

7It should be noted that since immigrants who were considered higher salariat in their country of origin (255 cases) could not have upward mobility, they were excluded from our sample when implementing the multinomial models.

8According to Ganzeboom et al. (1992) the ISEI scale more adequately captures variability between occupations as it is based on a continuous measure of the socio-economic situation.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken as part of the project Migration strategies and networks in contemporary Spain: A research effort based on the National Immigrant Survey funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CSO 2008-03616/SOCI). We would like to thank Miguel Requena, Lorenzo Cachón and Paul Schmelzer for helpful suggestions and comments.

References

AGUILERA, M.B. & Massey, D. (2003) 'Social capital and the wages of Mexican migrants: new hypotheses and tests', Social Forces, 82(2) p. 671–701.ALBA, A., Arranz, J.M. & Muñoz-Bullón, F. (2007) 'Exits from unemployment: Recall or new job', Labour Economics, 14 p. 788–810.

ALCOBENDAS, M.A. & Rodríguez-Planas, N. (2009) '"Immigrants" assimilation process in a segmented labor market', IZA Discussion Paper Series 4394, Institute for the Study of Labor.

AMUEDO-DORANTES, C. & de la Rica, S. (2007) 'Labour market assimilation of recent immigrants in Spain', British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2) p. 257–284.

ARANGO, J. (2004) 'La población inmigrada en España [in Spanish: Immigrant population in Spain]', Economistas, 99 p. 6–14.

BERNARDI, F., Garrido, L. & Miyar, M. (2011) 'The recent fast upsurge of immigrants in Spain and their employment patterns and occupational attainment', International Migration, 49(1) p. 148–187.

CACHÓN, L. (2009) La 'España inmigrante': marco discriminatorio, mercado de trabajo y políticas de integración [in Spanish: 'Migrant Spain': discriminatory framework, labour market and integration policies]. Barcelona: Anthropos Editorial.

CARBALLO-CRUZ, F. (2011) 'Causes and consequences of the Spanish economic crisis: why the recovery is taking so long?', Paneconomicus, 3 p. 309–328.

CEBOLLA, H. & González-Ferrer, A. (2008) La inmigración en España (2000–2007). De la gestión a la integración de los inmigrantes [in Spanish: Immigration in Spain (2000–2007). From the management of migratory flows to the integration of immigrants]. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Politicos y Constitucionales.

CEBOLLA, H. & González-Ferrer, A. (2013) La integración inesperada [in Spanish: Unexpected integration]. Madrid: Alianza.

CHISWICK, B. (1977) 'A longitudinal analysis of the occupational mobility of immigrants', in Dennis, B. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 30th Annual Winter Meetings (p. 20–27). Madison: Industrial Relations Research Association.

CHISWICK, B.R., Lee, Y.L. & Miller, P.W. (2003) 'Patterns of immigrant occupational attainment in a longitudinal survey', International Migration, 41(4) p. 47–69.

CHISWICK, B., Liang Lee, Y. & Miller, P. W. (2005) 'Longitudinal analysis of immigrant occupational mobility: a test of the immigrant assimilation hypothesis', International Migration Review, 39(2) p. 332–353.

COBB-CLARK, D.A., Connolly, M.D. & Worswick, C. (2005) 'Post-migration investments in education and job search: a family perspective', Journal of Population Economics, 18(4) p. 663–690.

CONSTANT, A.F. & Massey, D. (2005) 'Labor market segmentation and the earnings of German guestworkers', Population Research and Policy Review, 24(6) p. 5–30.

DEL RÍO, C. & Alonso-Villar, O. (2010) 'Occupational segregation of immigrant women in Spain', 2010-165, ECINEQ Working Paper 2010-165, Society for the Study of Economic Inequality.

DOMINGO, A., Gil-Alonso, F. & Robertson, G. (2007) 'Immigration and changing labour force structure in the Southern European Union', Population (English Edition), 62(4) p. 709–727.

ERIKSON, R. & Goldthorpe, J.H. (1992) The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Oxford: Clarendon.

ESPINOSA, K. & Massey, D.S. (1999) 'Undocumented migration and the quantity and quality of social capital. migration and transnational social spaces. Research in ethnic relations', in Pries, L. (Ed.), Migration and Transnational Social Spaces (p. 106–137) Sidney: Ashgate Publishing.

FERNÁNDEZ, C. & Ortega, C. (2008) 'Labor market assimilation of immigrants in Spain: employment at the expense of bad job-matches?', Spanish Economical Review, 10(2) p. 83–107.

FERRERO-TURRIÓN, R. & López-Sala, A. (2009) 'Nuevas dinámicas de gestión de las migraciones en España: el caso de los acuerdos bilaterales de trabajadores con países de origen [in Spanish: New dynamics of migration policies in Spain: the case of the bilateral agreements with countries of origin]', Revista del Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración, 80 p. 119–132.

FRIEDBERG, R.M. (2000) 'You can't take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital', Journal of Labor Economics, 18(2) p. 221–251.

FULLER, S. & Todd, F.M. (2012) 'Predicting immigrant employment sequences in the first years of settlement', International Migration Review, 46(1) p. 138–190.

GANZEBOOM, H.B., De Graff, P.M., Treiman, D.J. & De Leeuw, J. (1992) 'A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status ', Social Science Research, 21 p. 1–56.

GARRIDO, L., Miyar, M. & Muñoz, J. (2010) 'La dinámica laboral de los inmigrantes en el cambio de fase del ciclo económico [in Spanish: Immigrants labour market performance in turn of the economic cycle]', Presupuesto y Gasto Público, 61 p. 201–221.

GATHMANN, C. (2010) 'How general is human capital? A task-based approach', Journal of Labor Economics, 28(1) p. 1–49.

GURAK, D.T. & Caces, F. (1992) 'Networks shaping migration systems', in Kritz, M.M., Lean, L.L. & Zlotnik, H. (Eds.), International Migration Systems: A Global Approach (p. 150–189). London: Oxford University Press.

IZQUIERDO, M., Lacuesta, A. & Vegas, R. (2009) 'Assimilation of immigrants in Spain: A longitudinal analysis', Labour Economics, 16(6) p. 669–678.

KALTER, F. & Kogan, I. (2011) 'Migrant networks and labour market integration of immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Germany', paper presented at the conference Migration: Economic Change, Social Challenge, 6–9 April 2011, NORFACE/CReAM, London.

KAZEMIPUR, A. (2006) 'The market value of friendship: Social networks of immigrants', Canadian Ethnic Studies Journal, 38(2) p. 47–71.

LANCEE, B. (2010) 'The economic returns of immigrants' bonding and bridging social capital: the case of the Netherlands', International Migration Review, 44(1) p. 202–226.

MCALLISTER, I. (1995) 'Occupational mobility among immigrants: the impact of migration on economic success in Australia', International Migration Review, 29(2) p. 441–468.

MCGOVERN, P. (2007) 'Immigration, labour markets and employment relations: problems and prospects', British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2) p. 217–235.

MULDER, C.H. & Van Ham, M. (2005) 'Migration histories and occupational achievement', Population, Space and Place, 11(3) p. 173–186.

MULLAN, B.P. (1989) 'The impact of social networks on the occupational status of migrants', International Migration, 27(1) p. 69–86.

NANNESTAD, P., Svendsen, G.L. & Svendsen, G.T. (2008) 'Bridge over troubled water? Migration and social capital', Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(4) p. 607–631.

NEE, V. & Sanders, J. M. (2001) 'Understanding the diversity of immigrant incorporation: a forms-of-capital model', Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(3) p. 386–411.

PASCUAL, A., de Miguel, V. & Solana, M. (2007) Redes sociales de apoyo. La inserción de la población extranjera [In Spanish: Social support networks. Foreign population incorporation], Bilbao: Fundación BBVA.

PEDACE, R. (2006) 'Immigration, labor market mobility, and the earnings of native-born workers. An occupational segmentation approach', American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 65(2) p. 313–345.

PIORE, M. (1979) Birds of Passage: Migrant Labour and Industrial Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

POLAVIEJA, J. (2003) 'Temporary contracts and labour market segmentation in Spain: an employment-rent approach', European Sociological Review, 19(5) p. 501–517.

PORTES, A. (1998) 'Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology', Annual Review of Sociology, 24 p. 1–24.

PORTES, A. & Sensenbrenner, J. (1993) 'Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action', American Journal of Sociology, 98 p. 1320–1351.

POWERS, M.G. & Seltzer, W. (1998) 'Occupational status and mobility among undocumented immigrants by gender', International Migration Review, 32(1) p. 21–55.

POZZOLO, A. (1999) 'Human capital accumulation, social mobility and migrations', Labour, 13(3), p. 647–673.

RAIJMAN, R. & Semyonov, M. (1995) 'Modes of labor market incorporation and occupational cost among new immigrants to Israel', International Migration Review, 29(2) p. 375–394.

RAIJMAN, R. & Semyonov, M. (1997) 'Gender, ethnicity, and immigration: double disadvantage and triple disadvantage among recent immigrant women in the Israeli labor market', Gender and Society, 11(1) p. 108–125.

REDSTONE AKRESH, I. (2006) 'Occupational mobility among legal immigrants to the United States', International Migration Review, 40(4) p. 854–884.

REDSTONE AKRESH, I. (2008) 'Occupational trajectories of legal US immigrants: downgrading and recovery', Population and Development Review, 34(3) p. 435–456.

REYNERI, E. & Fullin, G. (2011) 'Labour market penalties of new immigrants in new and old receiving west European countries', International Migration, 49(1) p. 31–57.

ROOTH, D.O. & Ekberg, J. (2006) 'Occupational mobility for immigrants in Sweden', International Migration, 44(2) p. 57–77.

ROSE, D. & Harrison, E. (2007) 'The European socio-economic classification: a new social class schema for comparative European research', European Societies, 9 (3) p. 459–490.

SABATER, A. & Domingo, A. (2012) 'A new immigration regularization policy: the settlement program in Spain', International Migration Review, 46(1) p. 191–220.

SASSEN, S. (2001) The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

SEIFERT, W. (1997) 'Occupational and economic mobility and social integration of Mediterranean migrants in Germany?', European Journal of Population, 13 p. 1–16.

STANEK, M. (2011) 'Nichos étnicos y movilidad socio-ocupacional. El caso del colectivo polaco en Madrid [in Spanish: Ethnic niches and socio-occupational mobility. The case of the Poles in Madrid]', Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 135 p. 69–88.

STANEK, M. & Veira, A. (2012) 'Ethnic niching in a segmented labour market: evidence from Spain', Migration Letters, 10(3), p. 249–262.

VEIRA, A., Stanek, M. & Cachón, L. (2011) 'Los determinantes de concentración étnica en el mercado laboral español [in Spanish: Determinants of ethnic concentration in the Spanish labour market]', Revista Internacional de Sociología, 69(1) p. 219–242.