Hybrid Qualifications, Institutional Expectations and Youth Transitions: A Case of Swimming with or Against the Tide

by Gayna Davey and Alison Fuller

University of Southampton; University of Southampton

Sociological Research Online, 18 (1) 2

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/1/2.html>

10.5153/sro.2876

Received: 26 Jul 2012 Accepted: 5 Dec 2012 Published: 28 Feb 2013

Abstract

This paper uses the concept of hybrid qualifications to expose some of the ways in which the English system, with its longstanding academic and vocational divide, fails to support the transitions of young people with 'average' educational attainment. The concept of hybrid qualifications was developed during EU funded research undertaken in 2010 - 11 with project partners from Germany, Austria and Denmark. It was conceived to mean those qualifications generally achieved by young people aged 16-18 which would facilitate entry to the labour market or access to university. In the English system we defined Level 3 qualifications such as the BTEC National suite of Diplomas, Applied A-Levels, the Advanced Diploma and some qualifications contained within the Advanced Apprenticeship programme as contenders for hybridity. Compared with the clear pathways for entry to bachelor degrees that are articulated for those who have attained traditional academic qualifications (namely A-levels), the routes for those leaving school with vocational qualifications are poorly and narrowly-defined, and fragile. Using the rich, narrative data gathered from interviews and focus groups with students, tutors and key stakeholders, we illustrate how for this group transition often involves 'swimming against rather than with the tide'. To make sense of their uncertain and at times fragmented journeys we draw on Bourdieu's conceptual toolbox, and argue that his notion of 'doxa' is especially helpful in making sense of the way in which educational institutions play their own very distinctive roles in shaping those transitions.

Keywords: Vocational, Transition, Doxa, BTEC

Introduction

1.1 As numerous studies have shown, in the UK the qualification routes followed at 14 and 16 lead young people to particular places within the labour market, further or higher education (Furlong and Cartmel 2007; Brooks 2009; Gayle, Lambert and Murray 2009). Whilst only around a third of the post-16 cohort (Wolf 2011) study for traditional, academic qualifications, it is these young people that capture the public imagination and media attention each summer as successive cohorts proceed from GCSE to A levels and then to university (Fuller 2011). Moreover, with government policy initiatives focusing on university participation on the one hand, and the so-called NEETS, or approximately eight per cent of 16 to 18 year olds 'not in employment or education or training' on the other hand, those defined by their 'average', 'ordinary' and 'unremarkable' qualities risk being neglected (France 2007; Birdwell, Grist and Margo 2011; Roberts 2011, 2012). In terms of educational attainment, this includes the significant minority of young people (approx. 25%) pursuing broadly vocational or hybrid pathways at Level 3 (broadly equivalent to A-level standard). (Davey and Fuller 2010, 2011)1.2 This paper is concerned with young people whose transitions from school are neither characterised by what Roberts describes as the 'spectacular' issues of economic and employment marginalisation (Roberts 2012), or those who follow the clearly- defined and long-established route of general, 'traditional' qualifications to university participation. Whilst difficult to articulate as 'troubled' or 'fractured', these 'ordinary' young people are nonetheless 'swimming against the tide' as they negotiate the fragmented pathways and cul-de-sacs which are characteristic of all that is 'other' to traditional, academic trajectories (Fuller and Davey 2012).

1.3 To make sense of these less straightforward transitions we turn to Bourdieu's conceptual toolbox. A large body of Bourdieusian-inspired research has engaged with the social and cultural processes which impact upon young people's educational decision-making, and with habitus and capital widely adopted to explain the classed and gendered nature of those decisions. (Ball, Davies, Reay and David 2002; Hodkinson 1999; Hatcher 1998; Reay et al 2001, 2005). Particularly influential, the binary model of 'embedded' or 'contingent' choosers was developed by Reay and colleagues in their study of young people's higher education decisions (2005). According to this conceptualisation, educational trajectories are mediated through the closeness of fit between an individual's 'habitus', which is the embodied 'sense of the game' (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, p. 118) and the educational field. As 'embedded' choosers, middle-class young people are said to experience smooth, seamless transitions compared to the bumpy, problematic journeys faced by 'contingent' choosers, their working class peers. With the model of 'embedded' and 'contingent' choice we are offered a powerful device with which to illustrate the economic, social and cultural dimensions of young people's educational transitions, and how individuals' 'habitus' and capital accumulations shape those decisions. However, with our own empirical findings pointing to the importance of the role of the educational institution, we turn our attention towards the institution and its place in the field. We will argue that through the Bourdieusian concept of 'doxa' (1977, 1992) we can understand how the institution creates a distinctive taste for particular transitions via ostensibly the same educational programmes.

1.4 Having introduced this paper's key themes, let us now provide an outline of its structure. We begin with an overview of young people's patterns of participation, and in particular focus on the qualification routes followed by those aged 16-18. With the timing of our research coinciding with Professor Alison Wolf's review of vocational education in England (2011), we draw this section to a close by briefly considering the relevance to our discussion of some of its key points. Next, and after a summary of our methodological approach, the paper turns its attention to the conceptual and practical experience of 'hybrid qualifications', as illustrated by our empirical findings. We proposed hybrid qualifications in the English system as Level 3 qualifications such as the BTEC National suite of Diplomas[1], Applied A-Levels, the Advanced Diploma and some of the qualifications contained within the Advanced Apprenticeship. (See below for an account of how the concept of 'hybrid qualifications' was developed). We discuss their practical manifestation through the narratives of young people, further education tutors and the manager of a sixth-form college, considering their perceptions and lived reality of the concept. We then focus our attention on the influence of the institution and discuss how two colleges create starkly different understandings of the same qualification programmes. The institutional effect was something that emerged as a powerful and striking feature in our analysis and we discuss how the educational institutions, a further education college and a sixth-form, impacted on the choices made and paths followed by their vocationally-oriented students. To make sense of these institutional influences, we work with Bourdieu's conceptualisation of 'doxa' (Bourdieu 1977; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992). We discuss how the two institutions, occupying very different places in the field of 16-18 education, are engaged in the construction of what Davey (2009b, 2012) has described as a doxic understanding of educational decision-making. We argue that working with the concept of 'institutional doxa' offers a powerful means to understand and elaborate the enduring nature of the English system's binary oppositions. We conclude that the struggle to establish a clear identity for hybrid qualifications within the English educational landscape provides a powerful illustration of a system with no clear pathway and destination for those wishing to combine academic and vocational qualifications. Furthermore, that those academically 'average' young people are 'swimming against the tide' amidst poorly-defined progression routes and weak linkages between vocational education and the labour market (Fuller and Davey 2012).

Hybrid qualifications

2.1 The concept of hybrid qualifications was developed during EU funded research undertaken by the authors in 2010 – 11 (Davey and Fuller 2010; Davey and Fuller 2011; Fuller and Davey 2012). Working alongside partners in Germany, Austria and Denmark, the project initially constructed what can be understood as 'weak' and 'strong' definitions of 'hybrid qualifications'. The 'weak' version was loosely constructed and generalised, defined as any kind of combination of general (academic) and vocational learning age 14+ that formally qualifies for entrance to higher education and the labour market. This contrasted with a 'strong' version, which was a more tightly defined notion of hybridity and for which qualifications gave access to all higher education institutions, to bachelor degrees and across all subject areas. In this strong version, the ability to access the labour market was quite specific, and measured by the following features: whether the hybrid qualification leads to employment in the skilled labour market; provides a licence to practise; allows access to relevant professional body memberships; produces a positive wage return on qualification; leads to recognition by trade unions and other social partners; gives access to the next level of training, and access to work-based career pathways. Having completed literature and policy reviews, we adopted a weaker construction of hybridity, defining it to mean those qualifications at Level 3 in the English system, which is the standard expected for young people's entry to higher education, and also as having currency in the labour market.Patterns of participation

3.1 Students' achievement at 16 remains an important performance indicator, and the nature of progression beyond 16 is strongly associated with the attainment of five 'good' GCSEs. The achievement of five GCSE grades A* to C equates to a Level 2 qualification on the national qualification framework. Other ways of attaining Level 2 include: BTEC First Diplomas and Certificates, OCR Nationals and NVQ2s. Nevertheless, the notion of academic success, either for individuals or schools, is represented through varying articulations and conceptualisations of the GCSE. The award of five good GCSEs is commonly cited as an expectation for those wishing to pursue A level study, and those five GCSEs are increasingly expected to include at least English and mathematics. The recent introduction of the 'EBacc' (English Baccalaureate) by Michael Gove the Secretary of State for Education, to include attainment of A* to C grades in English, mathematics, a language, a science and either history or geography has reinforced the privileged status being assigned to traditional academic subjects[2]. Thus, the GCSE has established itself as symbolic and material currency in terms of future educational progression, and in particular the channelling of students towards the 'academic' or general education pathway.3.2 The proportion of young people achieving five GCSE grades A*-C has increased in the last two decades. Official figures for 2010/11 indicate that 58.2% achieved this benchmark including A* to C grades in English and mathematics, an increase of 3% on the previous year (DfE SFR03/2002). Whilst attainment at GCSE indicates the likelihood of future academic progression, and is used to measure an individual's potential to study GCE A levels, it remains strongly associated with factors such as social class, parental education, ethnicity, gender and disability which act as underlying and intersecting structural influences on young people's educational routes (Gayle et al 2009; Roberts 2009).

The enduring status of GCE A levels

3.3 GCE A levels continue to dominate as a post-16 qualification for those with 'good' GGSE grades and is the most likely pathway to attainment at Level 3. Data provided by a recent government statistical release on Level 3 achievements for candidates aged 16-18 shows that A levels comprised almost 70% of that total, and Applied A levels, which can be considered as their more vocationally-specific incarnation, makes up almost 4%. (SFR 01/2012). It is more difficult to pin down the precise nature of attainment of vocational Level 3 qualifications, as the statistics provide aggregates which limit differentiation between types of vocational qualifications. The lack of clarity about vocational attainments in comparison with the detailed and publicly available data about A level achievements is symptomatic of the secondary, 'Cinderella' status of vocational or hybrid programmes and pathways.

3.4 Despite the lack of detailed information about the take up and attainment of vocational qualifications, it is apparent that there are a growing number of 'vocational-related qualifications' (VRQs), as illustrated through generic data on awards and completions. An increase from 1.7 million to 2.1 million vocational related awards was reported from 2007/8 to 2008/9. The awards of National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) and Scottish Vocational Qualifications (SVQs) and VRQs from academic year 2005/6 to 2008/9 increased from 525,000 NVQ/SVQs awarded in 2005/6 to 849,000 awarded in 2008/9. For VRQs, the number of awards rose from 1,071,000 to 5,834,000 for the same period. (SFR 25, March 2010).

3.5 Government supported Apprenticeship programmes are also part of the overall landscape of vocational provision. Approximately 6% of 16 to 18 year olds start Apprenticeships. The majority of these pursue the Level 2 rather than the Level 3 programme and successful completion of an apprenticeship is associated with the attainment of a range of awards specified in sectorally based apprenticeship frameworks[3]. In the official figures, apprenticeship achievements are defined as the successful completion of an apprenticeship framework. Whilst the UK has seen a growth in the numbers of apprenticeships, this is seen most clearly for those aged 19 and over, with an increase in achievements from 46,200 to 116,900 for the period 2006/7 to 2010/11. For those aged under 19 there were 65,700 apprenticeship achievements in 2006/7, increasing to 83,300 in 2010/11. (SFR 16, October 2012).

3.6 Before turning to the project's methodology we first look briefly at the findings of Professor Alison Wolf's Review of Vocational Education (2011), which coincided with our research and provides a useful perspective on the contemporary policy context.

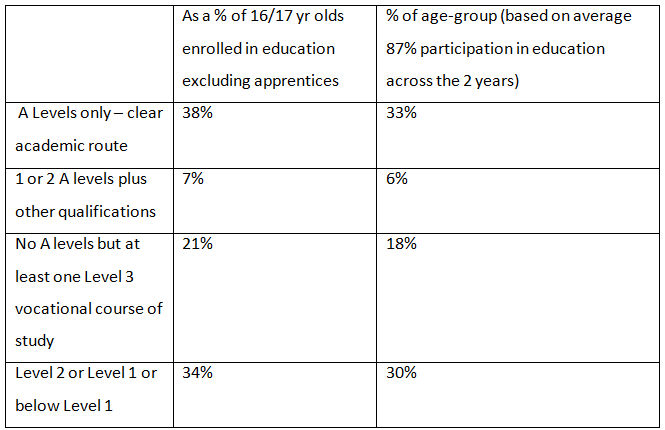

3.7 The coalition government commissioned report on Vocational Education by Alison Wolf provided some of up-to-date statistics on young people's post-16 participation. The vast majority, 94 per cent, of 16 year olds and 85 per cent of 17 year olds were participating in education in 2009-10 (Wolf 2011, p. 25). Table 1 presents a breakdown of the 'study programmes' of this age group in 2009-10

| Table 1. Study programmes of 16 and 17 year olds in educational institutions |

|

3.8 From the perspective of our interest in qualifications that facilitate access to HE or the (skilled) labour market, we can see that approximately a quarter of the cohort (taking together those that are pursuing a combination of A Levels and other qualifications, and those that are pursuing at least one Level 3 course other than A Levels) are pursuing a route that might be deemed to have hybrid status. Around a third of 16 and 17 year olds are pursuing qualifications at or below the Level they had been studying at 14 and 15. The currency of these qualifications is insufficient to provide access to either HE or the skilled labour market.

3.9 The Wolf Report found that vocational pathways are fragmented and poorly understood, with those 'who are ill-served….overwhelmingly outside the conventional academic tracks' (2011, p. 21). It is the accounts of those young people who are not following the 'conventional academic tracks' that illuminate our findings and provide that real-life dimension alongside the statistical picture. After describing our methodological approach we turn to those accounts.

Methodological approach

4.1 The paper is written following completion of a two-year study carried out with partners in Germany, Austria and Denmark, which aimed to improve understanding of the systems, qualifications and institutions which link higher education, vocational education and training (VET) and the labour market (Deissinger et al 2012). It was recognised that awareness, experience and understanding of the concept of 'hybridity' would vary across the four countries and so it was important therefore to adopt a qualitative approach to data collection that would facilitate in-depth exploration of the meanings and perceptions of a sample of key informants in each country. Our research project utilised qualitative interviews to gather perceptions and practical experience of 'hybrid qualifications' from a range of stakeholders across the educational, policy and employment landscape. The qualifications identified as potential contenders for hybridity were at Level 3, and are most commonly represented by the following: GCE Applied A Level; NVQ Level 3; BTEC and OCR National Diplomas. Although not a qualification, we were interested too in the Advanced Apprenticeship framework, as it can include Level 3 qualifications such as NVQ3 and BTEC/OCR National Certificates. We gathered data using interviews and focus group discussions with key informants including those in government departments, awarding bodies and educational institutions, as well as learners, tutors and employers. We interviewed 18 key informants, following a semi-structured interview format designed to elicit participants' responses to hybrid qualifications at an ideational and practical level. We also undertook two focus groups, one comprising students following BTEC National Diploma programmes in Health and Social care, Information Technology and Sport and Leisure; and one focus group with six tutors, two each from the same subject areas. These participants were all located in one further education college. Finally, we completed an interview with a young woman who had recently completed an apprenticeship in health and social care.4.2 In this paper we draw on three sources of interview data: an ex-apprentice; learners and tutors from a vocationally oriented college, and a senior manager at an academically-focused sixth form college.

Illustrative evidence and discussion

5.1 We will now draw from our qualitative research evidence, selecting examples from our interviews and focus group material. We begin with the case of a female apprentice. Next, through data gathered from the two focus groups, we hear real-life accounts of 'hybridity' emerging through practice. Finally, we turn our attention to an academically-oriented sixth-form college and through the narrative interview with a senior manager we examine how vocational educational programmes are conceived in this institutional setting.5.2 We begin by considering the case of 'Clare' and her narrative account of her aspirations for a career in social care.

Swimming against the tide: serendipity and resilience illustrated by Clare's Story

5.3 The story of a former apprentice, who we have called 'Clare', provides a lived example of the fragility, serendipity and risk associated with education – work transition and progression in the English 'system'. Clare is a care worker and is employed by a large local authority. Her name was given to us by two separate managers who were interviewed as key informants from that employer. It was clear she had gained a reputation as a hardworking and ambitious 22 year old. When we interviewed her she told us she was working in a care home and a studying for a foundation course with the Open University. She had completed a Level 2 Apprenticeship in Health and Social Care some months earlier. For her employers, she represented a success story, a triumph of a young person who had faced significant personal challenges in caring for a sick father, and whose pathway had been characterised by her personal resilience.

5.4 We asked Clare to describe how she had become an apprentice. Clare identified herself as '….(not) a bright student at all' and she added 'I wasn't in the like bottom sets or anything like that, but I was very average…'. Her transition to college from school was after having gained 8 GCSEs (grades A* to C), which actually puts her firmly in the top half of the achievement range. However, after a year of A level study in which she gained good passes at AS level (the first year of A level study, classified as Level 3) she left college and joined the post room of a law firm. Clare described how she gained promotion to an administrative role and then enrolled on an evening course to compliment her legal work. She successfully completed the first year of a four year legal studies course and gained a certificate.

5.5 Clare explained that she had had significant caring responsibilities for her father and this was one of the reasons that she left the legal firm. She said she had been inspired by a television campaign, 'Be the Difference', which promoted social work. Once she had seen that publicity, told us how 'she just clicked', and initially hearing nothing from her enquiry, secured an interview for an apprenticeship in health and social care some months later. The interview resulted in Clare being offered a Level 2 Apprenticeship with a large local authority employer, although her prior level of attainment was appropriate for entry to a programme at Level 3. Having successfully completed the apprenticeship, Clare explained that there was not the opportunity to progress to an Advanced Apprenticeship (Level 3).

5.6 It can be argued that there is a built in barrier to progression in the government supported apprenticeship system, which is illustrated by Clare's experience. A pre-requisite for the creation of apprenticeships is the availability of a job role which includes a range of work tasks and skills commensurate with the level of the apprenticeship. In the first instance, the job vacancy that Clare filled was mapped to a Level 2 Apprenticeship. For an Advanced Apprenticeship to be created, there needs to be a more skilled job role available than for its Level 2 counterpart. This approach reflects the concept and design of apprenticeships as vehicles for developing and accrediting the skills necessary to perform in specified occupational roles. For the apprentice to have the opportunity to generate the evidence necessary 'to pass' their competence assessments and be able to complete their apprenticeship framework, they have to have the opportunity to participate in the appropriate level of tasks. The close knit relationship between an apprenticeship and a job make it unlikely that an individual can progress from a Level 2 to a Level 3 apprenticeship unless an appropriate role becomes available. It also helps explain why an individual with the prior qualifications to enter an apprenticeship at Level 3 will be unable to do so if the only job available has limited skill requirements which map to the lower level framework specification.

5.7 Notwithstanding the disappointment of not being able to progress to the Advanced Apprenticeship, Clare has been fortunate. Her public sector employer has recognised her ability, evidenced not only by her performance at work but also by her academic background, which indicates her potential to progress to HE. At the time of the interview she was enrolled, with sponsorship from her employer, on the foundation year of a degree in Health and Social Care at the Open University. Clare hopes that the employer will be able to sponsor her though a bachelor degree in social work which will then enable her to progress to professional registration as a social worker. Clare's narrative, dominated by resilience and motivation, was indicative of the problems and barriers in the English system. Whilst her transition is not characterised by the 'spectacular' issues Steven Roberts has highlighted, it does provide an important story of how one young woman has navigated a path, albeit into a predominantly female sector, through unclear territory. Moreover, this is a story of false starts, cul-de-sacs and eventual opening of doors made possible through resilience and good fortune. Clare's transition from full-time education is informed by partial and ad hoc knowledge as well as gendered occupational expectations; and as such her decision-making processes remind us of Reay et al's 'contingent choosers' (2005). Having left her educational environment, Clare is forced to chart her own path helped by what one of our research participants, from an examinations body, described as the 'happy accident', or serendipity of finding herself working for an employer who recognised her potential and was willing and able to support her progress. Without this happy accident Clare was seriously at risk of falling through the weak 'safety net' that characterises the English education - work transition system (Raffe 2008) and distinguishes it from systems in other parts of Europe that are characterised by stronger safety nets, including Germany, Austria and Denmark (Deissinger et al 2012).

5.8 Clare's story, with its narrative theme of individual agency offers a contrast with the accounts of students engaged in full-time vocational programmes at a further education college. For those students, we will see the importance of the institutional context in giving shape to the contours of the middle ground they inhabit within the post-16 educational landscape.

Full-time vocational qualifications: a hybrid pathway?

5.9 The young people in our focus groups were following BTEC National Diploma programmes. When key informants and tutors were asked to characterise the kinds of students targeted by this provision, they agreed that it was designed for the average or above average achievers:

'…um most people will have got sort of Bs and mainly Cs kind of grades…' (HE programme leader)

'You don't get the high fliers [on BTEC courses' (BTEC programme tutor)

5.10 Overall, the students were very positive about their courses, and their responses exemplified the concept of hybrid qualifications as providing a valuable alternative to conventional academic study. This enthusiasm is encapsulated by the extract below:

'I quite like the BTEC because it prepares you for the industry you're going into… you've got work experience… units that are relevant to what you're doing… it also adds up so you know what you want to go and do if it's higher education, or straight onto working, they prepare you for that, the ins and the outs…' (Health and Social Care student)

5.11 Her programme leader perceived that the students' chances of accessing HE was enhanced by the opportunity they had to gain relevant work experience:

'...we have a good track record of getting our students on HE programmes and because they have a wealth of experience within the Health and Social Care setting that they can talk about on their personal statement… it actually makes them very strong candidates at interview' (Health and Social Care).

5.12 The organisation and availability of work placements was considered to be a key strength of the programme, and as this student explains:

'So we do three placements and like 100 hours overall, that's really good experience because you get to explore like all the different areas that you might want to work in and it's just really nice, just to have that option of going out and working in an environment you might work in future' (Health and Social Care student).

5.13 Moreover, as this interviewee told us, the combination of study and practice provided students with a beneficial hybrid experience that facilitated their educational and career decision-making:

'…I think where our students do benefit is, as somebody who came through the A-level route, went into nursing without ever having a very good idea what adult nursing was all about, I really feel that our students come onto our programme and through study units, through their work placements, through having my students come back to talk to them about their experiences, it helps them make decisions about where they would like to progress to after their BTEC' (Programme Leader, Health and Social Care)

5.14 The programme provided an opportunity to have 'tasters' of particular kinds of work and settings in the health and social care sector, which helped them develop their preferences. However, there was some variability in terms of the experiences across the student group; depending on their subject area. The positive experiences of work placements recounted by our Health and Social Care students were not universally available. Opportunities for work experience would be dependent on the vocational area being followed. For example, for students in the same college participating in the Sport and Leisure programme, there was an expectation that they arranged their own work experience where possible and resorted to asking for help from tutors only if that failed. For students on the IT programme authentic work experience was rare. We heard how minimum age requirements and strict rules on access to data presented particular barriers to placements for young people. Unless students had personal connections, work experience in this course constituted time spent supporting the college's IT help-desk.

5.15 The variability of work experience was one indication of a lack of consistency for students following what is ostensibly the same programme within the same institution. However more strikingly, and as we will discuss below, there were fundamental differences as to how those programmes were understood between the two educational institutions. What we explain below in terms of an 'institutional doxa' helps to make sense of the way in which educational trajectories are shaped by the boundary-making influence of each institution and its particular place within the field of education.

The Institutional influence

6.1 There is a large body of Bourdieusian-inspired research that seeks to identify the ways in which the school or college effect students' educational choices. (Reay, Ball, David 2001; Thomas 2002; Morrison 2009; Ingham 2009. Reay et al have been instrumental in developing the term 'institutional habitus', which refers to the mediating effect of an institution's reputation, status and practices (2001). However, as Davey observes, with habitus explaining individual action as an embodied and practical response to the field, to characterise an institution as having a certain habitus assigns it with subjectivity implied by the linguistic coupling of the words 'institutional' and 'habitus'. In doing so, there is an insinuation that the organisation has a habitus, which of course it does not. (2009, p. 81). Moreover, to use habitus in this way, as applied to an organisation, rather than the individuals within it, risks misappropriating the concept. Habitus is offered as a 'thinking tool' (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992) rather than a prescription for research methods, and its definition and application enjoy a mercurial quality. However, just as the wide and diverse nature of its use is indicative of its attractiveness, it is evidence too of what Davey has called a 'pick and mix' approach to Bourdieu's conceptual trilogy (2009, p. 4), which in isolating habitus from Bourdieu's overarching framework of habitus, capital and field neglects practice as it happens (2009, p. 259), and as Atkinson has argued allows habitus to be 'detached from the ontological framework in which it was forged' (2011, p. 344). So, in the construct of 'institutional habitus' we reduce the conceptual power offered by the trilogy of habitus, capital and field. The Bourdieusian sociology of practice, as it happens, with all the uncertainties, false starts and anxieties are virtually written out of the model. As Bourdieu states:Even in cases where the agents' habitus are perfectly harmonized and the interlocking of actions and reactions is totally predictable from outside, uncertainty remains as to the outcome of the interaction as long as the sequence has not been completed…. (Bourdieu 1977, p. 9).

6.2 Rather than using the concept of 'habitus' to explain the institutional effect, by turning our attention to the intersections between habitus, capital and field we can understand how the institution's place in that field shapes educational transitions. As Grenfell and James note, 'if habitus brings into focus the subjective end of the equation, field focuses on the objective' (1998, p. 15), and the concept of 'field' is a structured space, yet it is a space which relies upon individuals' willingness to accept its rules and play its particular game. As we will discuss through our empirical findings, each college has its own 'game', and establishes institutionally-specific understandings of its rules. The worth and exchange value of the same BTEC National Diploma programme can be understood as a stake in each institution's game. To encourage students to take part relies on a process of legitimating certain choices over others, with an institutional classification of the programme reflecting its position in the field of education.

6.3 To understand how the colleges develop seemingly natural, received understandings we turn to Bourdieu's conceptualisation of 'doxa'. As Atkinson observes, the concept transcends any one particular habitus (Bourdieu 2011, p. 344). By working with doxa we understand the structuring of decision-making processes through the relationship between individual habitus and institutional position in the field. The way in which Bourdieu conceptualises 'doxa' provides a means with which to pierce through what is otherwise taken-for-granted by the students, tutors and parents associated with those institutions, and is captured by Bourdieu as, 'what is essential goes without saying because it comes without saying ' (1977, p. 165-7). The way in which Bourdieu conceptualises 'doxa' goes to the heart of his sociological project, and the 'practical logic' that governs individual decision-making (1977). For Bourdieu, individual choices result from acquiring a sense of what is for them and what is for others, and he argues that an individual learns what hopes and aims are reasonable, as 'objective limits become a sense of limits, a practical anticipation of objective limits, sense of one's place which leads one to exclude oneself from the goods, persons, place and so forth from which one is excluded' (Bourdieu 1984, p. 471). Put simply, certain decisions are conceived as out of bounds, or captured through the once popular, colloquial phrase 'not for the likes of us'.

6.4 In Bourdieusian terms, the colleges have established a doxic understanding of transitions at 18, or what Davey (2009, 2012) describes as an 'institutional doxa' through the legitimating of certain decisions over others. By inculcating understandings of what it means to pursue a BTEC National Diploma, the colleges are creating particular, institutionally-specific meanings. The way it is positioned in the college's curriculum, the emphasis given by its tutors and the information and advice provided by careers advisors produces a distinctive flavour to an ostensibly national programme. Each institution can be seen as creating, and above all, legitimating its distinctive cultural capital in the form of the programmes' potential to offer employment and higher education destinations. With both colleges offering seemingly the same BTEC qualifications, each reflected the institutional perspective on these programmes as serving broadly academic or vocational and hybrid goals. Within the parameters of the BTEC National Diploma, the discussion below suggests how institutions create a taste for particular versions of following that programme, and perhaps more importantly the transitions which follow.

The vocationally-oriented college: creating hybridity through practice

7.1 The value and meaning attributed to the college's BTEC National programme reflected its reputation as a vocationally-oriented institution. Its tutors emphasised their knowledge of, and goodwill established with, local employers. It was the tutors' enrichment of the programmes by drawing on these links that enhanced the programme. In this way the college was able to position its BTEC National Diplomas as having meaning and value within the local labour market. However, as we noted earlier, there was considerable variation in the opportunities available for students to secure work placement. As such, it would be wrong to assume that the same vocational value could be attached to all three programmes. For example, the labour market currency associated with the IT programme had to be seen in the light of its limited opportunity for students to gain access to 'real' work experience during their two-year programme.7.2 Above all, the college's provision reflected a valuing of the 'practical' as well as the relevant vocational knowledge. In doing so, it defined routes for young people who had a tendency to identify themselves as academically 'average' and vocationally-oriented. For the tutors, the needs of employers were paramount. The ability of students to gain work experience alongside their Level 3 study, after completing the programme or following higher education, was a clearly-articulated expectation. For both the BTEC students and tutors, there was a desire to do something in the 'real world', something practical. Although the programmes attracted UCAS tariff points and so provided opportunities for progression to higher education, the ultimate goal was conceived in terms of labour market entry in a cognate occupational field and career opportunity. The understanding of qualifications and the progression routes they offered were anticipated in vocational terms, and moreover, in opposition to the students' 'bright' school friends, whose inclinations were more clearly academic.

Hybridity as bolstering the academic

7.3 The practical, vocational orientation of the programmes' positioning in the further education college was in marked contrast to the way in which the sixth-form college positioned itself. If the programmes offered by the further education college can be understood through the institutional doxa reflecting its position as a vocationally-oriented college, the second institution provides an example of a markedly different position in the field. Our interview with a senior manager provided an illustration of the 'institutional doxa' doing its work to steer students towards particular versions of higher education participation. Known for a strong record of Oxbridge and medical school entrants, the sixth-form enjoys a reputation as an elite institution and one for which applicants regularly exceeded places. With the emphasis on facilitating progression to elite universities, the vocational programmes offered at the sixth-form college were secondary to its more traditional academic curriculum offer. The college's celebration of transitions to traditional, 'high status' higher education institutions is clear and unashamed; as if deeply embedded within the fabric of its vocational programmes. The sixth-form college is creating a taste in its students to progress to selective, high-status universities.

7.4 Although predominantly offering A-level courses, the college offers a limited number of BTECs in Sport, Information Technology, and Health and Social Care. The findings below illustrate how the same subjects and qualifications are given quite different emphases depending on their institutional setting, adding another important factor affecting (the lack of) programme standardisation. The interview with the senior manager was characterised by an emphasis on all programmes in his college as providing credentials and currency for progression to HE. The BTEC National route was seen as a way of helping students to maximise the exchange value of their achievements at 18 as the design, delivery and assessment features of the course were seen to fit their abilities and interests, leading to their achievement of top grades.[1] According to our respondent, BTECs provide an alternative way for some students to secure places in a competitive and selective HE system.

'Our [BTEC] students, partly by the way they work, the nature of the courses, they get grades far in excess of what they would if they were following a traditional A-level course.''A significant proportion of them go into Loughborough, which has got a particular sporting reputation.'

7.5 He described too how there were increasing numbers of students using the BTEC National (usually the Award which is equivalent to one A-level) to complement 'hard' and the 'crunching' high status A-levels in science subjects, as a means of distinguishing themselves for selection to medical degrees. The interview narrative, although of course from the perspective of a senior manager rather than a tutor, was dominated by the education paradigm with an emphasis on access to highly competitive undergraduate programmes. Entry to the labour market was implicitly understood as following university participation.

Conclusions

8.1 This paper has focused on how hybrid qualifications are understood by those 'on the ground', and in doing so we have shown how the individual agency and commitment allow hybridity to emerge through practice. Through Clare's narrative, we heard how individual agency, some good fortune and some false starts too, eventually enabled her to find her way through to the beginnings of a career in social care. For the BTEC students, transitions were understood within the institutionally-specific meanings associated with their programmes. Through the concept of institutional doxa we can see how the college constructs its position within the field through the meanings it gives to what is superficially a standard programme. For the further education college, its status and reputation align to an employment paradigm, and whilst for many students the programme was followed by university, the emphasis is on the BTEC programmes as offering a stepping stone towards clearly-defined employment. For this institution, the ability to foster good relationships with local employers and for its students to gain meaningful work experience is an important measure of its success and position in the post-16 educational market place.8.2 In contrast, for the sixth form college, its status and reputation as an academic hot-house, and with what were referred to as 'aspirational' parents, aligns more closely to an academic paradigm. This college's reputation is maintained by an ability to negotiate and agree expectations of what constitute appropriately aspirational university destinations. Set amidst a predominantly traditional curriculum offer, the BTEC National Diploma was used to augment students' university applications.

8.3 The variability and context-dependent features associated with the BTEC National Diploma are in many ways indicative of the challenges of the English context. With a lack of standardisation, vocationally-oriented qualifications risk being misunderstood or mistrusted by employers and higher education institutions. For the BTEC National Diploma students, the ultimate currency of their programmes was influenced by both the vocational subject area of that programme and the institution in which they were studying.

8.4 The findings presented in this paper exemplify the continued academic/vocational divide which has for so long characterised the English system. Both colleges occupied distinctive places within that system. Their institutionally-specific understandings of the BTEC National Diploma programmes illustrate their contrasting positions along the academic/vocational continuum and the difficulty of reaching a clear definition of what occupies the space 'in between'. Furthermore, set against the relative stability and visibility of academic qualifications, the routes for those who are defined by their 'average' academic attainment are defined by opaqueness. For those young people the successful navigation of this middle ground is achieved through resilience and some degree of serendipity. Whilst the metaphor of 'swimming against the tide' is evoked most powerfully by the story of our female apprentice, it captures the instability and context related contingency associated for those young people whose transitions lie outside the conventional, academic route.

Notes

1 BTECs are graded Pass, Merit, Distinction, with Distinction accruing the same number of UCAS points as an A grade at A-level.2 BTEC National Diplomas have recently been renamed as Extended Diplomas. Our research was undertaken before this change came into force and our respondents were therefore still using the terminology of National Diplomas.

3 See <http://education.gov.uk/schools/teachingandlearning/qualifications/englishbac/a0075975/the-english-baccalaureate> for more detailed information about the introduction and content of the EBacc in England.

4For a detailed discussion about the content of apprenticeship frameworks and their currency see Fuller and Unwin 2011.

References

Government, grey literature and statistical releasesBIRDWELL, J., Grist, M. and Margo, J. (2011) The Forgotten Half. A demos and private equity foundation report. <http://www.demos.co.uk/files/The_Forgotten_Half_-web.pdf?1300105344.

DFE (January 2012) GCE/Applied GCE A/AS and Equivalent Examination Results in England 2010/2011 (Revised), SFR01/2012

DfE (February 2012) GCSE and Equivalent Attainment by Pupil Characteristics in England, 2010/11, SFR03/2012, London: DfE

DfE (July 2012) <http://www.education.gov.uk/a0064101/16-to-18-year-olds-not-in-education-employment-or-training-neet>, accessed 20 July 2012.

THE DATA SERVICE (October 2012) DS SFR 16 Post-16 Education and Skills: Learner Participation, Outcomes and Level of Highest Qualification Held. <http://www.thedataservice.org.uk/statistics/statisticalfirstrelease/sfr_current/> accessed 27 November 2012

WOLF, A. (2011) Review of Vocational Education – The Wolf Report. <http://www.education.gov.uk/pubications/eOrderingDowload/Wolf-Report.pdf>.

Academic

ATKINSON, W. (2011) From sociological fictions to social fictions: some Bourdieusian reflections on the concepts of 'institutional habitus' and 'family habitus'. British Journal of Sociology of Education 32(3), p. 331-347 [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2011.559337]

BALL, S J., Davies, J., Reay, D and David M (2002) 'Classification and judgement: social class and the cognitive structures of choice in higher education' British Journal of Sociology of Education 23(1), p. 51-72 [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01425690120102854]

BOURDIEU, P. (1977) An Outline of a Theory of Practice Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BOURDIEU, P. (1984) Distinction New York: Harvard.

BOURDIEU, P. and Wacquant, L. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology Cambridge: Polity.

BROOKS, R. (2009) (ed.) Transitions from Education to Work: new perspectives from Europe and beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

DAVEY, G. (2009a) Using Bourdieu's concept of habitus to explore narratives of transition, European Educational Research Journal. 8 (2), p. 276-284. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2009.8.2.276]

DAVEY, G. (2009b) 'Defining the middle classes: using Bourdieu's trilogy of habitus, capital and field to deconstruct the reproduction of middle-class privilege'. University of Southampton. Social Sciences. Doctoral thesis, p. 313.

DAVEY, G. (2012) Using Bourdieu's concept of doxa to illuminate classed practices in an English fee-paying school, British Journal of Sociology of Education. 33 (4), p. 507-525. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.662823]

DAVEY, G. and Fuller, A. (2010) Hybrid Qualifications – Increasing the Value of Vocational Education and Training in the Context of Lifelong Learning, England Country report, <www.hq-lll.eu>.

DAVEY, G. and Fuller, A. (2011) Best of both worlds or falling between two stools, England Country report, <www.hq-lll.eu>.

DEISSINGER, T., Aff, J., Fuller, A., Jørgensen, C. (2012) (eds.): Hybrid Qualifications: Structures and Problems in the Context of European VET Policy. Bern: Peter Lang.

FRANCE, A., 2007. Understanding youth in late modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

FULLER, A. and Davey, G. (2012) Transcending the academic – vocational binary in England?: An exploration of the promise of 'hybrid qualifications' in, Deissinger, T., Aff, J., Fuller, A., Jørgensen, C. (eds.) in: Hybrid Qualifications: Structures and Problems in the Context of European VET Policy. Bern: Peter Lang.

FULLER, A. (2011) What about the majority? Rethinking post-16 opportunities, in Mullan, J. and Hall, C. (eds) Open to Ideas: Essays on education and skills, The Associate Parliamentary Skills Group and National Skills Forum: London. Available to download at <http://www.policyconnect.org.uk/nsfapsg/open-to-ideas>.

FURLONG, A. and Cartmel, F. (2007) Young People and Social Change: New perspectives. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

GAYLE, V., Lambert, P. and Murray, S. (2009) 'School-to-Work in the 1990s: Modelling Transitions with large-scale datasets', in Brooks, R. (ed) Transitions from Education to Work, London, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 17-41.

GRENFELL, M. and James, D. (1998) Bourdieu and Education: acts of practical theory, London, Falmer Press.

HATCHER, R. (1998) Class differentiation in education: rational choices? British Journal of Sociology of Education 19 (1), p. 524. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0142569980190101]

HODKINSON, P.M. (1999) "Use of Habitus, Capital and Field in understand young people's career decision making', in Pierre Bourdieu: Language, Culture and Education, Grenfell, M., Kelly, M. (eds). Bern: Peter Lang.

INGRAM (2009) Working?class boys, educational success and the misrecognition of working?class culture. British Journal of the Sociology of Education, 30 (4) p. 421–34.

MORRISON, A. (2009) Too comfortable? Young people, social capital development and the FHE institutional habitus, Journal of Vocational Education and Training 61 (3) , p. 217-230.

RAFFE, D. (2008) The concept of transition system, Journal of Education and Work, 21 (4), p. 277-296. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13639080802360952]

REAY, D., David, M. and Ball, S. J. (2001) Making a Difference:

Institutional Habituses and Higher Education Choice, Sociological Research Online, 5 (4) <http//www.socresonline.org.uk/5/4.reay.html>.

REAY, D David, M E, Ball, S. J. (2005) Degrees of choice: social class, race and gender in higher education. Stoke on Trent: Trentham.

ROBERTS, K. (2009): Opportunity structures then and now, Journal of Education and Work, 22 (5), p. 355-368. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13639080903453987]

ROBERTS, S. (2011) Beyond NEET and tidy pathways: considering the missing middle of youth studies, Journal of Youth Studies, 14 (1), p. 21-39. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.489604]

ROBERTS, S. (2012) No Snakes, but no ladders: Young people, employment and the low skills trap at the bottom of the contemporary service economy. The Resolution Foundation downloaded on 5 July 2012. <http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/media/downloads>.

THOMAS, L. (2002) Student retention in higher education: the role of institutional habitus. Journal of Education Policy 17 (4), p. 423-442. B