My Family and Other Animals[1] : Pets as Kin

by Nickie Charles and Charlotte Aull Davies

University of Warwick, Swansea University

Sociological Research Online 13(5)4

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/13/5/4.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1798

Received: 22 Jul 2008 Accepted: 4 Sep 2008 Published: 30 Sep 2008

Abstract

The title of this paper gives a family-like character to animals and an animal-like character to the idea of family. It emphasises the close, family and friend-like relationships that can exist between human beings and the animals who share their domestic space. This type of relationship between humans and their pets emerged during a study of families and kinship and in this paper we draw on 193 in-depth interviews conducted in four contrasting areas of a South Wales city. Although our interview schedules did not explicitly ask about animals, a significant proportion of our interviewees spontaneously included their pets as part of their kinship networks. There were two points during the interview when the significance of pets became apparent: when interviewees were asked who counted as family and when they were asked to complete a network diagram. In studies of kinship it has been said that pets are substitutes for children, providing emotional satisfaction. Here we explore some of the other ways in which animals are constructed as kin and discuss whether such constructions confound the (socially constructed) boundary between nature and culture.

Keywords: Pets, Animals, Family, Kinship Networks

Introduction

1.1 The title of this paper, which is the title of an autobiographical account of an animal-filled childhood on Corfu by the naturalist, Gerald Durrell, gives a family-like character to animals and an animal-like character to the idea of family. It ignores the distinction between social and natural, human and animal. In similar fashion, Donna Haraway, in her Companion Species Manifesto, deconstructs the binary which separates nature and culture, eliding them as natureculture and discussing the joy of 'training' her four legged friend or, more accurately, learning with her how to create an effective human-animal partnership for competition agility. Both these authors, in different ways, underline the close, family and friend-like relationships that can exist between human beings and the animals who share their domestic space. And both expose the permeability of the species barrier which allegedly separates humans from other animals (Durrell 1959; Haraway 2003). This species barrier has, for centuries in the west, been defended by science, religion and moral philosophy but is increasingly being brought into question (Midgley 1983; Rowlands 2002). Indeed a recognition of the connectedness of humans with other animals and the interdependence of human society and nature is leading to a reconceptualisation of the place of humans in the natural world, something which is allegedly essential for the survival of the planet and which is referred to in the use of the term 'post-humanism'. As James Serpell points out, however, 'human beings are still extremely reluctant to admit that the line which separates them from other species is both tenuous and fragile' (Serpell 1996: 167); something which has been underlined by recent debates in Britain over proposals in the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill to create embryos which mix human and other animal biological material (The Guardian 20/5/08). It is not the purpose of this paper to explore these debates but we mention them because they provide some indication of the social and political relevance of the ways in which we conceptualise relationships between human and non-human animals and between society, culture and nature. In what follows we look briefly at how this conceptualisation has changed and the implications of this for the ways in which we relate to non-human animals, particularly pets. We then describe our study of patterns of family formation and kinship networks which, quite unexpectedly - because in our interviews we did not ask people about their animals - suggests that pets, or companion animals as they are increasingly referred to, are regarded as active members of people's social networks and, in many cases, as members of their families. [2]Ambivalence

2.1 It has been argued that the relationship between humans and other animals is one of ambivalence (Serpell 1996; Arluke and Sanders 1996). It is only recently that this ambivalence has begun to be investigated sociologically although there is considerable debate about how it relates both to the development of human societies and to religious and philosophical schools of thought. Anthropologists, for instance, suggest that hunter-gatherer societies had a very different relationship to animals and nature than is the case for pastoral societies. Thus Tim Ingold argues that in hunter-gatherer societies the relationship between humans and other animals was one of trust. He contrasts this with the domination that has defined this relationship since the advent of pastoralism and agriculture (Ingold 1994). The difference lies in the fact that hunters in hunter-gatherer societies do not seek control over animals whereas pastoralists seek 'to secure the compliance of the other by imposing one's will, whether by force or by more subtle forms of manipulation'. This is 'an abrogation of trust, entailing as it does the denial rather than the recognition of the autonomy of the other on whom one depends' (Ingold 1994:16). Furthermore, he argues that 'the transition in human-animal relations that in the western literature is described as the domestication of creatures that were once wild, should rather be described as a transition from trust to domination' (Ingold 1994:18). Thus the dominion of 'man' over the 'beasts of the field' is associated with domestication and an understanding of the relation between humans and other animals as uni-directional, hierarchical and involving control. It is interesting that some biologists contest this view of domestication using evidence from anthropology as well as from the natural sciences (Grandin and Johnson 2006; Haraway 2003). Temple Grandin argues, for instance, that wolves influenced the evolution of humans just as much as humans influenced the development of dogs from wolves and, in the process, the brains of both species were altered (Grandin and Johnson 2006: 305-6). She concludes, 'Dogs and people co-evolved and became even better partners, allies, and friends' (Grandin and Johnson 2006:306) and Donna Haraway points out that this evidence of co-evolution has been used 'to question sharp divisions of nature and culture' (Haraway 2003:30). Stephen Budiansky argues further that proto-dogs associated with humans for a lengthy historical period 'by their own volition' (Budiansky 2002:24).

2.2 These interpretations of co-evolution and domestication by choice of the animal are, however, recent developments and contrast strongly with the view that has hitherto dominated western thought. This view holds that there is a strict division between humans and other animals and that humans are superior, particularly in the use of language. This superiority is justified in different ways depending upon whether it is religion, moral philosophy or natural science that is constructing the argument (Birke 1994). Thus within the 'Judaeo-Christian philosophical tradition' the earth and all within it was created to serve 'man'; all other animals were inferior to human beings (Serpell 1996:150). The negative view of animals in relation to humans has also been linked to Aristotle for whom reason was what separated 'man' from the animals (Serpell 1996:151). In the 13th century Aquinas argued that the souls of animals did not survive their death, unlike those of humans; this was because the only part of the soul that survived was associated with reason and animals did not possess reason (Serpell 1996). 'In the West, both the religious and the secular moral traditions have, till lately, scarcely attended to any non-human species' with the religious tradition denying them souls and the secular tradition denying them reason (Midgley 1983:10). The seventeenth century rationalists excluded 'concern for animals from morality' (Midgley 1983: 45) and Descartes, for one, argued that animals were no more than machines having no mind and being unable to feel pain (Rowlands 2002). Similar arguments about souls and reason were applied to slaves and to indigenous peoples in the Americas during the Spanish conquest and, as Mary Midgley points out, to women and to other groups that were considered external to those who were doing the defining (Midgley 1983). And, as feminists have argued at length, Enlightenment thought abrogates rationality to men and 'male priests, doctors, and scientists have declared animals a territory to be approached with objectivity and detachment' (Hogan et al. 1998:xii). Some Enlightenment thinkers, however, dissented from this view and, as Tim Newton remarks, there is a tradition of anti-dualism in western thought (Newton 2007) and, since at least the seventeenth century, there has been a trend which emphasises the interconnections between humans and animals (Birke 1994:32). There is also a thread within the Judaeo-Christian tradition which values nature and kindness towards other animals; this is associated with, amongst others, Francis of Assisi (Serpell 1996). This notwithstanding, secular thought since the Renaissance 'has largely been "humanist" in one sense or another, sometimes even in the very strong sense of putting man [sic] in the place of God' and this has fixed 'the limits of morality to the species barrier' (Midgley 1983:11). Now, however, philosophers are arguing that concepts of rights and equality can and should be extended to 'the borders of sentience', a development that 'has been made possible by the other liberation movements of the sixties' (Midgley 1983:65) and the idea of post-humanism has emerged. This rejects the claim that humans are different and special and asserts that we are also an animal species no more or less important than any other.

2.3 The ambivalence that is said to characterise the relationship between humans and animals of other species therefore arises from the contradiction between, on the one hand, recognising the affinity between humans and other animals, caring for them and forming attachments to them and, on the other, exploiting them, killing them to eat or simply for pleasure and regarding them as possessions akin to 'things' (Midgley 1994; Serpell 1996). 'There is real reverence, there is admiration, there is some mutual trust, there is also callous and brutal exploitation' (Midgley 1994:193). The moralities, religious and secular, that developed along with the shift to pastoralism and which defined 'man's' moral supremacy to animals, thereby creating the species barrier between humans and other animals, are, some suggest, functional to human societies. This is because they legitimate the exploitation of animals in the form of 'hunting, domestication, meat eating, vivisection (which became common scientific practice in the late seventeenth century) and the wholesale extermination of vermin and predators' (Thomas 1983:41). Thus in contemporary western societies, the pig 'on which a major section of our economy depends, supremely useful animals in every respect' has a quality of life imposed on it by humans which 'suggests nothing but contempt and hatred' (Serpell 1996:19). There is, however, a class of animals that are treated differently. In James Serpell's words, 'They make little or no economic contribution to human society, yet we nurture and care for them like our own kith and kin, and display outrage and disgust when they are subjected to ill-treatment' (Serpell 1996:19). These animals are pets and this difference embodies 'two totally contradictory and incompatible sets of moral values' (Serpell 1996:19).

2.4 The ambivalence which characterises humans' relationships with other animals, however, also characterises our relationships with pets. Thus Rebekah Fox argues that pets occupy 'a liminal position on the boundaries between 'human' and 'animal'' (Fox 2008:526). As well as being seen as 'minded individuals' they are also regarded as possessions which can be discarded when they are no longer needed or useful or convenient; the number of pets which end up in animal rescue centres testifies to this (Arluke and Sanders 1996). Furthermore, on the basis of her empirical research, she suggests that pets are seen by their companion humans as both 'human' and 'animal'. When constructed as 'human' they may be a valued family member with their own individuality and when constructed as 'animal' they are seen in terms of instincts and as essentially different from humans. This relates to different types of animal and reflects a hierarchy which places reptiles and insects below mammals and birds (see also Arluke and Sanders 1996). What it also indicates, we would suggest, is that humanist categories are at work in constructing how people view animals and that a post-humanist abandonment of binaries has not permeated the common sense understanding of human-animal relations. Indeed, it has been argued that the analytical distinction between humans and animals, or society and nature, should not be abandoned and that the practical transgression of boundaries, which is increasingly undertaken by scientists (but which is also a condition of life – whether 'human' or 'animal' – see for example Haraway 2008), may herald yet another way of exploiting animals rather than breaking down the categorical distinctions which legitimate such exploitation (Birke 1994; Newton 2007).

Researching Pets

3.1 Relatively little attention has been paid to the social phenomenon of pet keeping by sociologists which must in some way relate to the species barrier which has kept the social and natural sciences separate (Midgley 1994; cf Fox 2008 in relation to geography; Newton 2007). Anthropologists have, however, been more interested in human-animal relations although this interest often relates to non-industrial societies. Their work shows that pet keeping is not something that is confined to affluent, western societies but is also practised in hunter-gatherer societies. In these circumstances pet keeping cannot be seen in terms of extending social relationships to include animals as a response to the decreasing solidarity of human social relationships. In industrial societies, however, attachment to pets is often seen as a substitute for other social and, particularly, familial relationships. It has been suggested, for instance, that the sentimentality of the English in relation to pets derives from the fact that pets are a source of emotional satisfaction and can 'act as substitutes for children' (Strathern 1992:12; see also Anderson's work on parrots, 2003). The idea that pets substitute for a lack of other social relationships is not borne out by research, on the contrary pets are more likely to be found 'amongst couples, families with children, and in large households than… among single or elderly people' (Serpell 1996:40; Bonas et al. 2000). There is, however, evidence that animals facilitate social connectedness (Knapp 1998; Wood et al. 2007) and the main reasons cited for keeping a pet are companionship or friendship (Serpell, 1996:107). In some senses, therefore, it could be argued that pets contribute to the formation of social capital.

3.2 Pets are also a source of important types of support and 'human-pet relationships, particularly those with dogs, provide a source of some elements of support comparable with levels from human relationships' (Bonas et al. 2000:232; Enders-Slegers 2000). This suggests that there are similarities in the relationships between pets and humans and humans with each other. Indeed pets are often referred to as family members and/or as friends, they are seen as providing emotional support and as 'knowing' how their companion human is feeling. Unsurprisingly, given this level of attachment, they are mourned when they die and are frequently buried or cremated but 'the usual sources of social support are not available to a bereaved pet owner' (Enders-Slegers 2000:240; Arluke and Sanders 1996). Moreover grief and distress on the death of a pet indicates that 'the human-animal bond' is a primary relationship (Enders-Slegers 2000:253). Overall, research shows 'that the vast majority of western pet owners regard their pets as members of the family; that they talk to them, share their meals with them, allow them to sleep on the bed, and to sit on the furniture and even to celebrate their birthdays' (Serpell 1996:74; Serpell and Paul 1994).

3.3 Not only are animals seen as fictive kin, as a recent study of parrots shows, but they are also endowed with agency (Anderson 2003). This is reflected in the way people 'talk for' pets in visits to the vet or when trainers explain their course of action in relation to a particular dog; people translate into language the feelings and motivations of their animal companions (Arluke and Sanders 1996). Pets are regarded as 'minded social actors' and seen as intentional, 'self-aware, planning, empathetic, emotional, complexly communicative, and creative' (Arluke and Sanders 1996:43). Moreover people talk of themselves as if they were the parents or even grandparents of family pets and this language has also been noted when animals are being placed for 'adoption' (Arluke and Sanders 1996; Haraway 2003).

3.4 It seems therefore that pets are commonly seen as kin and as having agency and that people establish meaningful and supportive relationships with their companion animals. Most existing research has focussed on the relationships between companion animals and their humans rather than exploring whether and how animals may become part of social networks. In what follows we explore some of the ways in which animals become fictive kin, focussing particularly on the part they play in family and kinship networks.

The Study

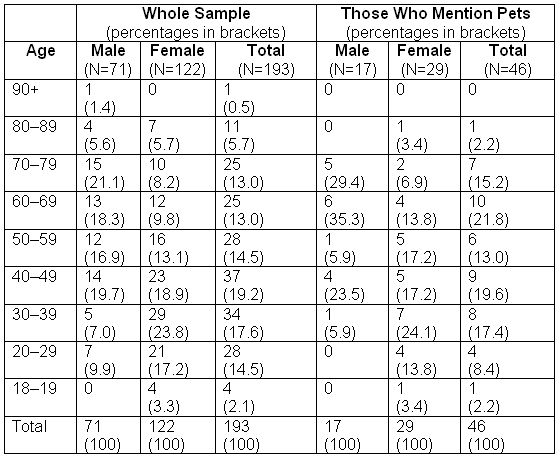

4.1 Our study was designed to explore patterns of family formation and kinship networks and was a re-study of Rosser and Harris's 1960 research into the family and social change (Charles, Davies and Harris 2008; Rosser and Harris 1965). It consisted of a thousand-household survey and 193 in-depth interviews and was carried out between May 2001 and December 2003 in Swansea, South Wales. Our primary concern was with patterns of residence and contact between members of families living in different households and how these had changed since 1960 when the original study was carried out. The ethnographic interviews, which we draw on in this paper, were carried out in four different parts of the city. The areas were selected on the basis of their contrasting socio-economic and cultural composition in order to explore whether patterns of family formation and kinship networks were influenced by variables such as class, culture and age. We interviewed 122 women and 71 men aged between 19 and 92 years (see Table 1).

|

| Table 1. Gender and Age Breakdown of Sample Showing Those Who Mention Pets |

4.2 The interviews were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim. The samples in the four areas were constructed using a snowball technique with several different starting points such as churches, schools, community organisations, shops and personal contact. It was more difficult to find men than women who would agree to be interviewed and this is reflected in the gender composition of our samples. This difficulty has been encountered by others conducting research on families (and also on pets, see Fox 2008) and is an indication of the strong cultural association of families with women. The interview topics included who counted as family, the importance of family, the nature of contact with family members, family occasions, social networks, the nature of support given and received and questions of identity and family change. The social significance of friends and neighbours was also included and attempts were made to ensure that interviews were conducted with respondents living in a variety of different household types and living arrangements. Our research was not, therefore, designed to investigate the significance of pets in kinship networks nor did we ask about animals; despite this, however, interviewees spontaneously offered accounts of the place of animals in their families.

4.3 The fact that our data derive from a study that did not intentionally set out to examine the role of animals in families has methodological implications, both positive and negative. The principal strength of data acquired in such an 'accidental' fashion is the confidence thereby gained that reactivity is minimised. Our interviewees introduced the subject of pets as family members entirely spontaneously, on their own initiative, without any suggestion from the interviewer that this was relevant or of interest to us. We did not identify this as a potential area of investigation until all interviewing was complete and we began to analyse our data. Thus we believe that our data on this topic are very robust, certainly in the sense of not being affected by our preconceptions.

4.4 Clearly, minimising reactivity is not equivalent to eliminating reflexivity. Our theoretical (as well as personal) interest in human-animal relations no doubt prompted us to see significance in these comments by our interviewees and not to dismiss them as simply amusing idiosyncrasies – as indeed occurred in the baseline study carried out in the 1960s. Furthermore, the fact that all three interviewers lived with companion animals meant that their interaction with interviewees who wanted to talk about animals as family members was empathetic and accepting of their comments.

4.5 The main disadvantage of data whose significance is not recognised until data collection is complete is that only the information interviewees choose to present is available; it is not possible to probe for further details, clarify meanings or get at nuances of interpretation. For this reason, no claims can be made for the comprehensiveness of the data, and the findings must of necessity be regarded as exploratory and suggestive of further research.

4.6 In the course of the interview we asked interviewees to complete a network diagram, something that has been used by others investigating people's personal networks (see for example Pahl and Spencer 2004b; Phillipson et al. 2000). The network diagram consisted of three concentric circles with the interviewee at the centre. Interviewees were asked to complete the diagram putting all those who they could not imagine living without in the innermost circle and using the middle and outer circle for those who were important to them but slightly less so. We stressed that we were moving away from family at this point of the interview to explore interviewees' social networks. It was often here that the significance of pets became apparent and, even though we did not explicitly ask for information about pets or even indicate that pets might be included in these diagrams, seven (4 per cent) of our interviewees included pets in their network diagrams and 46 (24 per cent) mentioned animals at some point in the interview (see also Spencer and Pahl 2006:51). The proportion of women and men who spoke about animals was the same as their proportions in the sample as a whole (37per cent were men) but of those including animals in their network diagrams, five were women and two were men. Similarly, those mentioning animals were to be found across the age spectrum from 19 to 85 years of age (see Table 1) and they lived in a variety of situations from being on their own to being part of large, extended families. There were no real differences between the four ethnographic areas in the proportion of people mentioning their pets and talking about them in kin-like ways, with the exception of the area where a high proportion of our interviewees were Asian and Chinese. Here the number mentioning companion animals was lower which is not unexpected given the significance of pets in British constructions of kinship (Strathern 1992).

4.7

In what follows we explore the ways in which pets are talked about in the interviews and the extent to which they are regarded as 'kin'. There were two points in the interview where pets were mentioned spontaneously: when interviewees completed the network diagram and when we asked them who they counted as family. We look first at the inclusion of animals in the network diagrams and then at the ways in which interviewees talked about pets.

Network Diagrams

5.1 It was often when we asked interviewees to complete their network diagrams that they talked to us about their pets and seven interviewees decided to include them in their diagrams. Five of this seven listed them in the inner circle, one denoting what might be seen as his ambivalence about doing so by putting 'DOG!' in brackets and near to the edge of the innermost circle; another wrote the name of her dog across the line between the innermost and middle circle. Six of the animals so included were dogs and it was mainly dogs who were put in the inner circle; one woman listed her cats in the middle circle and another included her horses as well as the family dog in the inner circle. Dogs were also the most-frequently mentioned animals with 35 of the 46 interviewees who talked about animals speaking about dogs. A man in his 40's, for instance, who was married and had no children, included in the inner circle of his network diagram his wife and several boyhood friends ('I'm probably closer to them than some people are to their brothers'), who were dispersed across Europe but with whom he maintained contact. He included in the other circles his nieces and nephews, some of his wife's cousins, his father-in-law and his partner and his wife's siblings, but was careful to point out that 'the mother-in-law isn't here'. In addition, he drew the interviewer's attention to another member of his network, the family dog, who was in the inner circle: 'Very important part of the family. [Interviewer: Yes. /laughs/ You are not the first one.] German dogs, Schaeferhunds' (F043). Another man would have included his cat and dog in his network but his wife completed the diagram for him and left them out. He said to his wife when asked to fill in the diagram, 'Well the closest family is obviously you, Mick and Maureen [their children], isn't it. I would include the dog and the cat. /laughs/' (F051).[3]

5.2 This over-representation of dogs ties in with other research which suggests that dogs provide greater levels of support to their human companions than do other animals (Bonas et al. 2000). Indeed one of our interviewees, while including her dog excluded her cat, claiming to be a 'dog person' rather than a 'cat person'. In spite of this preponderance of dogs in our study it is not only dogs who are seen as fictive kin and as sources of support. Research on keepers of companion parrots has found that these birds are often thought of as family members ('fids', feathered kids) and are a source of emotional support to their human partners (Anderson 2003). Cats, horses and, by one informant each, fish and a budgie as well as dogs were included in the network diagrams completed by our interviewees.

5.3 The inclusion of pets was always commented upon, most often by asking the permission of the interviewer to include a pet (see also Spencer and Pahl 2006).

Int And, and on the other two circles are people who are still close but not quite so close. And if you could put relationship then…

Res Okay. So… what if I put partner? He's not my husband yet.

Int Yes.

Res Now see, even though we haven't got a good relationship, I have to put my mother in that one as well?

Int Yes.

Res Because, you know? She's still my mother, you know?

Int Yes. Unless, closeness is not, it's, it can be full of conflict too, can't it?

Res Can, can I just put friends or I don't, or 'friend one' or what?

Int Yes, Yes. Put them in…

Res I'll put down friend one?

Int Yes. Yes.

Res Right? Because I know who I'm thinking of and I'll put just friends then in the general…

Int Yes.

Res Cats. Can I get them in there?

Int Of course.

Res Because I was devastated, I lost one of my cats last, a year last Christmas and I still choke up every time I think of him. 'Oh, my little babies'. (TR02)

This woman included in the inner circle her son, daughter, partner, brother, mother and a friend. In the middle circle are her cats, more friends, her cousins, uncles and aunts. The cats are therefore not as close or important to her as some members of her social network but they rank alongside friends, and cousins, aunts and uncles who were often defined as more distant family by our interviewees (Becker and Charles 2006).

5.4 It was common for interviewees to treat the inclusion of their pets in these diagrams – an inclusion that they themselves raised – in a joking manner. Thus one man suggested including his fish by saying the opposite, that they would not be included, and then went on to talk about how important they were to him.

Res Well, I don't think the fish would have much to do with it! [laughter] [Interviewer goes to look at fish tank while the respondent fills in diagram]

Int Some people even put their dogs on, you'd be surprised who we get in this circle. We meet all sorts in this job!

Res They're good company actually.

Int I know. I've had fish.

Res They know when I'm going to feed them.

Int Oh god, don't they just.

Res Because they come rushing down to this end and they're jumping about. And…

Int And I can put my feet up and just watch those fish. (TR044)

5.5 Another couple, whose home was full of dog memorabilia such as photographs and rosettes, illustrated the tendency to list pets with other family members but to lessen the impact with laughter:

Res Yes as I said I've got four boys.

Int Yes, yes, obviously

Res's wife Seven grandchildren, three dogs. /laughs/

Int Have you got three dogs now?

Res Yes

Res's wife Yes. I did have five. /laughs/ But we lost one New Year's Day, and we gave one away to a home in Bath.

Res /fills in diagram/

Res's wife I love my dogs. (PC044)

5.6 These kinds of responses, either attempting to lessen with laughter the impact of including animals as family or using joking references to introduce them into the discussion, seem to reflect the ambivalence of human-animal relations discussed earlier and the awareness that having too close a relationship with animals may be viewed negatively. Thus interviewees tended to 'test the water' to see how the interviewer would react to any revelations about animals as family members.

Who Counts as Family?

6.1 The other point in the interview when interviewees spontaneously mentioned animals was when we asked who they would count as family. The responses to this question support the idea that people make choices about who they count as family (Charles, Davies and Harris 2008; Pahl and Spencer 2004a; Hansen 2005; Weeks et al. 2001) and suggest that some ideas of family are more open to the possibility of non-human animals being categorised as kin. Some interviewees defined family in terms of 'blood' or marriage, a definition which makes it difficult to include pets, based as it is on consanguinity and affinity. Others, however, understood family differently and, for them, friends were often 'like family'.I think basically it's people, people who are there for you. People that you can turn to and people who you love. I think that's … my definition of family then. (T002).

6.2 This points to the importance of support and the quality of the relationship in defining who is and is not counted as family and makes it possible to include friends and non-human animals as family members. Indeed a significant proportion of interviewees spontaneously mentioned animals when we asked them who they would count as family. One of the women offered the following description of her family.

Right, I'm married, for twenty-seven years, in two weeks time. [Very good /laughs/] I've got one son, he is twenty-five, and we've got a daughter who is nearly eighteen. And a dog. (PC036)6.3Another woman who had been divorced twice and was now living with her 'two illegal cats' (illegal because she was living in a flat where animals were not allowed) said,

So that's my family really, two cats. [Interviewer: So they are family. /laughs/] My brother thinks I'm a lunatic, "get them put down you are asthmatic. You shouldn't spend a lot". (M044)

6.4 Animals who were counted as family were usually members of interviewees' households although they were also mentioned, along with other family members, by people living away from home, in particular students living away from their natal family. Thus one young woman said, 'Yeah, okay. I've got a mum and dad, and my, I have a younger brother Jonathan who is ten, and a dog, and they all live in [county]' (F040). Animals were also sometimes mentioned when describing extended kinship networks and, in the example below, neither divorce nor the species barrier are relevant when defining who counts as family.

Oh yeah, oh yeah both parents and both married sides I would say are family. …//…And my sister and her partner as well, yeah, my grandma, I've got one grandma who is alive, so obviously my grandma, my dad, Amy that's his wife, my mum, Robert her husband, my sister, her partner, her dog, /laughs/ and Pete's family. (PC021) [3]

6.5 These examples show that the criteria used by interviewees to define whom they counted as family varied. For some a 'biological' connection was paramount (thought of colloquially as being related by 'blood') while, for others, it was about the quality of the relationship and the support that people, kin or friends, offered. Sometimes the two operated in combination (see also Becker and Charles 2006). The assumption of available support, however, was nearly always part of the explanation of why friends were like family and why certain family members were particularly close. A woman in her thirties, living with her partner and their two children, said:

What makes somebody family? Well family are blood relations isn't it, but I would consider, if you are looking at it in a different type of way, I would consider Donna and Cath [her two best friends] to be closer that way than my own family are, they are more of a, you know, I think I can ask them for more than I could ask from my own mother, most of the time, without being criticised or judged for anything you know. (PC023)

Support and Pets

7.1 Clearly the provision of support is important in defining who is family and defining pets as kin may also relate to the provision of support. Pets are involved in support in two ways: on the one hand, looking after each other's pets is a way of providing support for kin, friends and neighbours and, on the other hand, pets can themselves be a source of support and companionship. One of our interviewees said:If my mother goes away I look after the dog, I go down and look after the house, and if she wants anything, I'll do anything for her, and my sister like. If I go out to the shop and she wants anything, I just, you know, do it. (PC009)

7.2 And a couple, who were about to go away on holiday, reported that their son and his wife would 'come up and stay here …//… and look after the house and the dogs' (PC043). While dogs were often cared for by family members, neighbours more commonly looked after one another's cats:

The people in the middle house are going on holiday tonight for three weeks so we've got their keys because we look after their cat. [You see to the cats?] Yes, they've got five cats and we look after them. And we've only just lost our one cat because we had five as well but they all sort of died off because they were all old. (TR033)

7.3 The relevance of support in explaining how animals come to be counted as family links to findings from other research which shows that pets provide their companion humans with significant levels of support, particularly emotional support and, in the idiom used by most of our interviewees, they are 'there' for their human companions (Bonas et al. 2000; Enders-Slegers 2000; Anderson 2003). This was evident in our study in the way that interviewees talked of their grief at the loss of an animal companion, a response that emphasises the close ties between many pet owners and their animals. For example, a woman, when completing her network diagram in which she eventually included her dog, referred to the earlier loss of a pet dog as an indication of the closeness of the ties:

You don't include animals. [That's up to you.] Well, do you know, my first dog died, it was like my first big grief experience. It was. It was bigger than anything I'd had before, even my grandmother had died, but yes, I'd say dog comes across that line there. (P014)

7.4 Another interviewee, a 42-year-old man, spoke of his grief when their dog, who he said had been 'part of the family', died and contrasted it to his grief at the loss of other close family members:

Anyway, anyway, he died and we were so heart-broken. It was just … [I know] It was, what I've found is like, with a person like my mother, it was, it was more of a long-term thing. But with a dog, it was very intense or for a short period and then you've got over it. But with people then, it's not as intense, but it's for a longer period. (TR037)

7.5 The importance of animals to their human companions was often commented upon, not only when speaking about grief for the loss of a pet but also when talking about the companionship provided by pets. This is illustrated by the experience of one of our interviewees, a widow in her seventies who lived with her cat. She told us about him.

He's company, another living creature in the house and I make sure he's in at night, you know? He's been getting, six o'clock in the morning he wants to get, go out then it's been moving back to five o'clock and this morning, it was three o'clock, he wanted to go out! So, I had to get up and let him out and wait for him to come back in again because I don't like leaving him out because there are a lot of squirrels and he's getting elderly, you know? (TR09)

7.6 Sometimes people were involved in helping neighbours to look after their animals and recognised the importance of their companionship. For example, a man who was married and living with his wife reported, 'next door but one is a spinster and she's got five cats. And we try to help her'. Although he presented this neighbourliness as being an effort to help an 'eccentric' old woman, he was clearly very devoted to the cats himself. The only photographs on the wall of the room where the interview took place were of the neighbour's cats, photographs that the neighbour had given to him and his wife along with other little gifts.

Res She's a… well. One of the nicest cats ever.

Int Oh, that's rather nice, isn't it? Oh, she looks very nice.

Res Oh he's a, brilliant, he used to come up, see? He used to come up often before Alan put the fence up, see?

Int Ah, right.

Res And of course, Iris was annoyed about that. I mean, the other cats, no problem but Barney, Barney's about 20 now, you see?

Int Oh, blimey!

Res Aye, lovely cat.

Int Ah, he hasn't got long then, has he?

Res She fetched, she fetched him up for my birthday. /Laughter/ (TR032)

Pets as Social Actors

8.1 The importance of animals as companions and the way they are taken into account in decisions about family activities such as visits or where to live indicates that pets can also be considered actors in social networks. The widow who lived with her cat provides an example of the way that considerations regarding animals affect decisions about living arrangements.I think sometimes, it would be more convenient if I had a little flat somewhere but this is home. [Yes. Yes] And I've got a cat and he wouldn't like being in a flat because we did have him in a flat when we were over there when the house was being redone and he wasn't happy at all, bless him. (TR009)

8.2 It is commonly assumed that animals become important to people either when they are living in single-person households, in which case they provide companionship, or as child substitutes. We found examples of both in our data. Thus, for the older woman quoted above, her cat provides companionship. And another woman had constructed her dog as a child. This was going to have to change, however, and she told us how she was attempting to re-negotiate the role of her Yorkshire terrier since discovering she was pregnant:

We've had him two years now, he's been the baby see, because I wasn't going to have more children, and I don't know how he's going to react when this baby comes. He was terrible with the budgie. [Interviewer to dog: You are going to be jealous.] Yeah, because I did baby him quite a bit, but tried not to since I found out I was pregnant, I've tried to, not to distance myself but to, just tell him who is boss type of thing, so he started to realise he is a dog not a child. /laughs/ So we'll see when the baby comes anyway. (PC025)It is significant that she says he will have to realise that 'he is a dog not a child' as it suggests that the boundaries between human and non-human animals are not fixed and that they can easily be transgressed; this is particularly clear when pets are constructed as children.

8.3 There are, however, many other ways in which pets become actors in social relationships and they can be the cause of strained relationships both within families and between neighbours. One woman, for instance, reported that her mother particularly objected to her recent acquisition of a Rottweiler puppy because of a concern that it might harm the children. And another reported that she and her husband had stopped going to stay with her sister because 'they've now got a dog, and the dog doesn't like my husband. He doesn't like men at all. /laughs/', although they continued to call when they visited other members of their family in the area (F006). Another couple complained about visits from their son and his family, which consisted of two children and two 'bloomin' big dogs' (F007), partly because they lived in a bungalow, but also because they felt their own small dog had trouble with the visitors.

8.4 As these examples suggest, animals may be a source of conflict, or at least irritation between family members; nor is this necessarily or even usually resolved in favour of the human family members. Several interviewees expressed a definite preference for animal companions over some particular family members. For example, as already noted, one man specifically drew our attention to the fact that his circle diagram included his dog but not his mother-in-law.

8.5 More commonly, however, and as we have seen in the above examples, pets are reported as a focus of reciprocal social relationships between people (such as looking after one another's animals), and as providing a way of meeting others and making links within a community, particularly for people new to a neighbourhood (cf. Wood et al. 2007).

Well, they first accepted me in [this] Street because as you know, Parkfields is full of cliquey little old areas … I'd been living here about five years, way before [her daughter was born], and I got myself a dog. Not [her current dog] ... and that, I was accepted then …//… people that come up to you and talk to you and talk to you about your dog or talk to your dog. (P014)

8.6 Animals are also sometimes the means of establishing much broader social networks. Thus one of our interviewees, a man in his seventies, was completely focussed on his rescue greyhounds and his work with animal charities. And a couple, who were in their 60's and who we mentioned earlier, had been breeding and showing dogs for over 30 years. This was an activity that connected them to a national network.

Husband We don't smoke, we don't drink, and that's, it's a hobby for us and it gets us out. So…

Wife And we've got friends everywhere then you see, all over the country. (PC044)

8.7 These examples illustrate some of the ways in which animals can be actors in social networks. They not only bring people together by needing to be looked after if their keepers are away but they also shape where people live and, crucially, influence the way networks operate. This is apparent in the way that family members change their behaviour in response to animals, by choosing not to stay with a sister on a family visit for instance, and in the way that human contact can be fostered by a shared interest in animals. Thus dogs may facilitate the creation of social networks in neighbourhoods by enabling strangers to strike up conversations, share dog-walking activities and, perhaps, become friends (see for example Knapp 1998). By the same token they can create conflict which may lead to a weakening of social networks as some of our interviewees suggest.

8.8 The social networks that animals help to create and in which they play an active part can be conceptualised in terms of bonding social capital (Charles and Davies 2005). It may be that some pets not only provide companionship themselves but enable their humans to provide companionship for each other. Given the limitations of our data, our findings here are suggestive, but it would appear that this is an area of social life that would benefit from further research.

Discussion

9.1 What is abundantly clear from our findings is that animals are regarded as important members of kinship networks and that they operate as social actors within these networks. Our interviewees talked to us about their animals and about how they were significant to them and to their families even though we did not ask specifically about animals. More broadly, however, there are three themes that emerge from our data: the cultural construction of kinship, the ambivalence surrounding human-animal relations, and the significance of non-human animals as actors in social relationships.9.2 The cultural construction of kinship was evident in the way interviewees talked about their families, who they included and the bases of that inclusion. For some, family was defined in terms of consanguinity or affinity, but it became clear that choice was exercised when defining who counted as family. The underlying rationale for these choices cannot be understood in terms of normative rules defining relational categories, although in many cases such rules appear to underpin the choices made. Neither can it be seen as based in any simple way on 'biology', although again this featured in the way some interviewees rationalised the inclusion and exclusion of certain categories of kin and/or individuals. Our evidence suggests that the boundaries between relationships that are 'given', in terms of consanguineal and/or affinal links, and those that are 'chosen' are not necessarily salient in understanding how definitions of family and kin are constructed (cf. Pahl and Spencer 2004a). Most of our interviewees considered some 'blood relatives' to be family and others not, and they usually selected some affines as family and rejected others. In addition, the majority included friends in their definitions of family, although there was a tendency for those who had close-knit and extensive kinship networks to include fewer friends than those whose kinship networks were more loose-knit and more geographically dispersed.

9.3 It seems clear from this that family and kinship are socially constructed and that different rationales are used to justify the choices made. This of itself is not an unusual finding. But what we are suggesting also is that this construction may ignore the species barrier thereby recognising the possibility of kinship between humans and other animals. Our interviewees chose who counted as family and who was included in their social networks from the categories not only of kin, friends and neighbours but also animals, and in exercising this choice, friends and animals became defined as 'kin'.

9.4 As well as constructing pets as kin, the way people talked about their animal companions betrayed an uncertainty about how this relationship might be construed by the interviewer. This was evident in their testing of the water to see how their wish to count pets as family or to include them in their network diagrams would be taken and, we would suggest, can be seen as an indication of the ambivalence with which animals are regarded within western culture. This ambivalence has a long history and is associated with an understanding of close relations between humans and animals as 'unnatural'. Inter alia this harks back to the witchcraft trials of early-modern Europe where a close association with an animal, particularly of women with their familiars, was taken as a sure sign of witchcraft (Serpell 1996). There is also a sense in which close, intimate relations with pets is seen as an indication of inadequacy and an inability to form appropriate relations with other humans. And admitting that your own relationship with an animal is meaningful may attract the charge of anthropomorphism; such meaningful relatedness is something which is regarded as particularly inappropriate for adults.

9.5 The species barrier is maintained by such ideas of inappropriate intimacy and, in many fairy tales, intimacy, in the form of a kiss, with what appears to be an animal usually leads to a reversion to human being; such a reversion is sometimes regretted and/or played with (Kenna 2008; Carter 1981). In contrast, some modern stories, such as Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy, portray intimacy with animals as a condition of life (Pullman 1995, 1997, 2000). The reversion to humanity from a 'beast' (or a frog) in effect reinforces the species barrier, a barrier which is socially constructed and maintained in the face of a whole wealth of evidence and experience of the importance of animals to humans – not only as a resource to be 'husbanded' but also as living creatures who enter into meaningful social relations with humans, both on an individual and group level.

9.6 Our data also provide evidence that animals play an active part in social relationships, they create connections between human social actors and operate as nodes in social networks. Pets were involved in creating social connections: within families, communities and beyond. They were regarded as fictive kin and also as companions and friends. Clearly, the species barrier is no obstacle to pets being defined as kin and as being endowed with agency. This is not to say that they are necessarily regarded as human, although in some ways they might be(Fox 2008), but that they are included as actors in their own right in social relationships. The 'sharp divisions of nature and culture', to use Haraway's words (Haraway 2003:30), are, therefore, brought into question in these daily practices of kinship which demonstrate the connectedness of humans and other animals and the permeability of the categorical barriers and boundaries that separate them.

Acknowledgement

This article draws on data generated as part of the research project 'Social Change, Family Formation and Kin Relationships' which was funded by the ESRC (R000238454) and carried out in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Swansea University by the authors and Chris Harris.

Notes

1With apologies to the late Gerald Durrell whose book, My Family and Other Animals, made a huge impression on one of the authors when she was a child.2A note on terminology .It has been argued that contemporary conditions of post-modernity are associated with a shift in relations between humans and other animals such that boundaries are becoming blurred and anthropocentric relations, often involving domination, are being replaced by relations of empathy and understanding (Franklin 1999:188-9). These shifts are captured theoretically in the use of terminology which attempts to move beyond the dualisms of western thought. Thus the binary human/animal is replaced by the terms human and non-human animals which allegedly imply a connection rather than a disjunction between humans and animals. Furthermore it is suggested that the use of these terms recognises that humans are themselves animals while the use of the binary human/animal does not. In this paper we generally talk about humans and animals, often qualifying the word animals with adjectives such as companion, other, human and, at times, non-human. Of course this carries no implication that humans are not animals, they quite clearly are. However what it does imply is that we remain unconvinced that it is time to abandon the categorical distinction between humans and animals, a view that is reflected both in the way we use terminology and in our argument. There are also those who suggest that the use of the term 'pet' is demeaning and implies that animals are kept by humans 'as entertaining playthings or fashion accessories' (Franklin 1999:180) and that, like the 'housebound wife' they suffer 'the indignity of underemployment or uselessness' (Plumwood 2002: 260, n33). The term companion animal, in contrast, implies that rather than being useless and ornamental, pets have some utility for their keepers, and although they may no longer be performing a job of work, their role as companions is socially significant and confers some dignity upon them. In much that is written about companion animals the terms are, however, used interchangeably (see for example Garner 2005: 137-9). We understand the use of the term 'pet' to imply an affective bond between humans and other animals – the dictionary definition of pet is 'any animal that is domesticated or tamed and kept as a favourite, or treated with fondness' (SOED 1973) – and because of this, and although both terms can be found in this article, we tend to refer to those animals who share human animals' domestic space as pets.

3All names used in quotations have been changed.

References

ANDERSON, P K (2003) 'A bird in the house: an anthropological perspective on companion parrots' in Society and Animals, 11 (4):

ARLUKE, A and Sanders, C R (1996) Regarding animals, Temple University Press: Philadelphia

BECKER, B and Charles, N (2006) Layered meanings: the construction of the family in the interview, in Community, Work and Family, 9 (2):101-122

BIRKE, L (1994) Feminism, animals and science: the naming of the shrew, Open University Press: Buckingham/Philadelphia

BONAS, S, McNicholas, J and Collis G M (2000) 'Pets in the network of family relationships: an empirical study' in A L Podberscek, E S Paul and J Serpell (eds) Companion animals and us: exploring the relationships between people and pets, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, pp. 209-236

BUDIANSKY, S (2002) The truth about dogs: the ancestry, social conventions, mental habits and moral fibre of canis familiaris, Phoenix: London

CARTER, A (1981) The bloody chamber and other stories, Penguin

CHARLES, N., Davies, C and Harris, C (2008) Families in Transition: patterns of family formation and kinship networks, The Policy Press: Bristol

CHARLES, N and Davies, C (2005) 'Studying the particular illuminating the general: community studies and community in Wales' in Sociological Review, 53 (4): 672-690

DURRELL, G (1959) My family and other animals, Penguin: Harmondsworth

ENDERS-SLEGERS, M-J (2000) 'The meaning of companion animals: qualitative analysis of the life histories of elderly cat and dog owners' in A L Podberscek, E S Paul and J Serpell (eds) Companion animals and us: exploring the relationships between people and pets, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, pp 237-256

FLYNN, C P (2001) 'Acknowledging the "Zoological connection": a sociological analysis of animal cruelty' in Society and Animals 9 (1):

FOX, R (2008) 'Animal behaviours, post-human lives: everyday negotiations of the animal-human divide in pet-keeping' in Social & Cultural Geography, 7 (4): 525-537

FRANKLIN, A (1999) Animals and Modern Cultures, Polity Press: Cambridge

GARNER, R (2005) Animal ethics, Polity Press: Cambridge

GRANDIN, T and Johnson, C (2006) Animals in translation: using the mysteries of autism to decode animal behaviour, Bloomsbury: London

THE GUARDIAN NEWSPAPER, 20/5/08

HANSEN, K.V. (2005) Not-so-nuclear families: Class, gender, and networks of care, New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press.

HARAWAY, D (2003) The companion species manifesto: dogs, people and significant otherness, Prickly Paradigm Press: Chicago

HARAWAY, D (2008) When species meet, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis

HOGAN, L, Metzger, D and Peterson, B (1998) Introduction in L.Hogan, D. Metzger and B.Peterson (eds) Intimate nature: the bond between women and animals, Fawcett Books/The Ballantine Publishing Group: New York, pp.xi-xvi

INGOLD, T (1994) 'From trust to domination: an alternative history of human-animal relations' in A. Manning and J. Serpell (eds) Animals and human society: changing perspectives, Routledge: London and New York, pp.1-22

KENNA, M (2008) 'Beauty and the Beast: an anthropological approach to a fairy tale', paper presented to GENCAS, Swansea University, June 21st

KNAPP, C (1998) Pack of Two: The Intricate Bond Between People and Dogs, Delta: New York

MIDGLEY, M (1983) Animals and why they matter, University of Georgia Press: Athens

MIDGLEY, M (1994) 'Bridge-building at last' in A. Manning and J. Serpell (eds) Animals and human society: changing perspectives, Routledge: London and New York, pp 188-194

NEWTON, T (2007) Nature and sociology Routledge: London and NewYork

PAHL, R and SPENCER, E (2004a) 'Personal communities: not simply families of 'fate' or 'choice' in Current Sociology, 52 (2):199-221

PAHL, R and Spencer, E (2004b) 'Capturing personal communities' in C.Phillipson, G. Allan and D. Morgan (eds) Social networks and social exclusion: sociological and policy perspectives, Ashgate: Aldershot, pp. 72-96

PHILLIPSON, C, Bernard, M, Phillips, J and Ogg, J (2000) The Family and Community Life of Older People: Social Networks and Social Support in Three Urban Areas, London: Routledge

PLUMWOOD, V (2002) Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason, Routledge: London

PULLMAN, P (1995) Northern Lights, Scholastic Point: London

PULLMAN, P (1997) The Subtle Knife, Scholastic Point: London

PULLMAN, P (2000) The Amber Spyglass, Scholastic Point: London

ROSSER, C and Harris, C C (1965) The family and social change, RKP: London

ROWLANDS, M (2002) Animals like us, Verso: London and New York

SERPELL, J (1996) In the company of animals: a study of human-animal relationships, (first edition 1986) Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

SERPELL, J and Paul, E (1994) 'Pets and the development of positive attitudes to animals' in A. Manning and J. Serpell (eds) Animals and human society: changing perspectives, Routledge: London and New York, pp 127-144

SOED (1973) The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press: Oxford

SPENCER, L and Pahl, R (2006) Rethinking friendship: hidden solidarities today, Princeton University Press: Princeton and Oxford

STRATHERN, M (1992) After nature: English kinship in the late twentieth century, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

THOMAS, K (1983) Man and the natural world: changing attitudes in England 1500-1800, Allen Lane: London

WEEKS, J., Heaphy, B. and Donovan, C. (2001) Same sex intimacies: Families of choice and other life experiments, London: Routledge.

WOOD, L J, Giles-Corti, B, Bulsara, M K, Bosch, D A (2007) 'More than a furry companion: the ripple effect of companion animals on neighbourhood interactions and sense of community' in Society and Animals, 15 (1):