Women Parenting Together: A reflexive account of the ways in which the researcher's identity and experiences may impact on the processes of doing research

by Kathryn Almack

University of Nottingham

Sociological Research Online 13(1)4

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/13/1/4.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1669

Received: 2 Jul 2007 Accepted: 19 Feb 2008 Published: 21 Mar 2008

Abstract

It is often suggested that in carrying out research into the lives of LGBT people, researchers have an advantage if they share the same sexual orientation with their respondents including greater access to respondents and the production of research accounts that perhaps have greater validity. However the process of doing research and writing up research is more complex than this suggests. In this article I seek to examine some of these assumptions in greater depth. A central (although not exclusive) concern of feminist debates is the extent to which the researcher's identity and experiences impact on the processes of doing research - and as such, the extent to which these should be made explicit. In examining some of these complexities, I draw upon these debates, the experiences of other researchers in the field of LGBT research and my own research examining the family lives of twenty lesbian parent families in the UK. I conclude that the ways in which the researcher may be positioned as an insider/outsider in research can be complex and these issues are particularly salient when choosing research topics to which the researcher has some level of personal and/or political commitment.

Keywords: Hidden Populations; Insider/outsider; Lesbian Parent Families; Research Methodologies; Sensitive Research; Qualitative Research

Introduction

1.1 The process of doing research raises a whole series of methodological, ethical and political debates. A key aspect of such debates is the extent to which the researcher's social location and subjectivity impacts on the process of gathering, analysing and writing up research data. These concerns may be particularly salient when researchers have a personal or similarly deep commitment to their research topic and are often highlighted in research into aspects of LGBT lives.1.2 In LGBT research, it is often claimed that a shared identity (in terms of sexual orientation) with one's respondents is an asset often with a particular focus on issues of access and recruitment. For example, Haimes and Weiner (2000) state that the lesbian identity of one of the interviewers was 'central' to gaining access to interviewees (and also to the formulation of their research project). Dunne (1997) believes that many women in her study into 'lesbian lifestyles' would not have agreed to be interviewed had she not been 'out' as a lesbian researcher. Similarly Browne (2005) contends that her sexuality played a 'significant role' in the recruitment of participants. Heaphy et al., (1998:456) also suggest that the willingness of respondents to take part in their study was in part influenced by the fact that the researchers disclosed their own gay and lesbian identities to respondents.

1.3 These discussions sometimes contain the further notion that shared identities (in terms of sexual orientation) assist the development of rapport in the interview setting. For example, Dunne (1997:24) argues that her lesbian identity helped to establish 'high levels of trust necessary for conducting sensitive research'. Such accounts may carry an implicit assumption that LGBT researchers are best placed to conduct interviews with LGBT populations.

1.4 Gabb (2004) further states that:

Insider status of researchers in this field is all but routine, in fact I have yet to read any work on lesbian parent families where the researchers' lesbian status is not highlighted at the outset and situated as crucial to the research process (2004:170)[1]

1.5 In this article I seek to examine and problematise some of these routine assumptions in relation to recruitment, rapport and reciprocity in the interview setting, researcher status as 'insider' / 'outsider' and some of the implications for the stories told, heard and written about. I also question the common-place practice for researchers in the field of LGBT research to be explicit about their own sexual orientation. In examining these issues further, I draw upon feminist methodological debates that informed my research exploring the family lives of lesbian mothers. Of course feminist methodology is not the only approach which can inform LGBT research but it has focused (albeit not exclusively) on several key aspects that are also central to LGBT research. These include considerations around the development of reflexive accounts of research and on the dilemmas inherent on researching sensitive topics to which the researcher has a particular personal attachment. I also draw upon my own experience in carrying out a qualitative research project in the UK which is a sociological investigation into motherhood and the family lives of same sex (female) couples who planned and had their first and subsequent children in the context of their current relationship.

Women parenting together the study

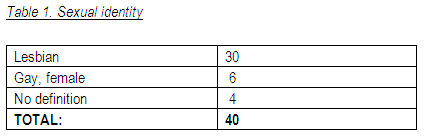

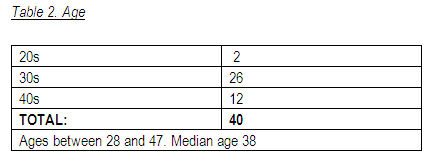

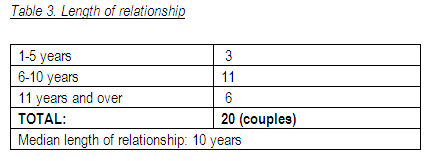

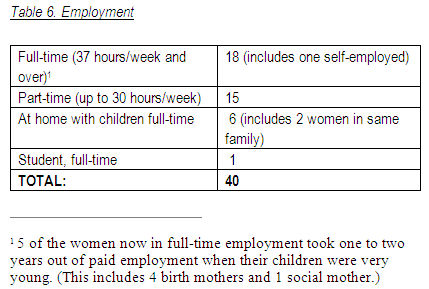

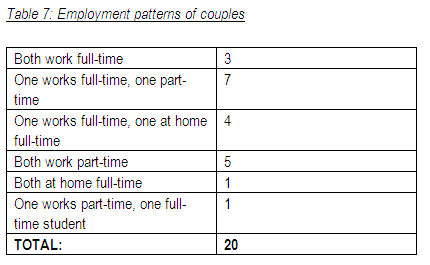

2.1 The focus of this study was on lesbian couples who planned and had their children in the context of their relationship. This was designed to investigate a family form that is innovative but which also involves the care of dependent children, with the aim of contributing to debates about the possibilities and challenges of parenting within the context of an increasing diversity of family forms and concomitant public concerns that have been expressed about these developments. My sample criteria included the decision to only interview couples who had had their first (and any subsequent children) within their relationship and whose children were aged 6 and under. Pathways to lesbian parent families are diverse but having children by insemination within a same sex relationship is perhaps one of the more radical family forms to emerge in the recent history of Western family lives Additionally, by keeping my sample criteria narrow, I was able to avoid variables of wider social processes at play, such as the dynamics and wider family relationships of 're-constituted' families. Weeks, et al. (2001), for example, state there were many different dynamics at play in their respondents' accounts of same sex parenting in different situations.2.2 I recruited 20 lesbian parent families in the UK and carried out my fieldwork in 2000 and 2001. This involved a set of joint and separate interviews with each couple at one point in time - a total of sixty interviews. In the joint interview I covered themes around the couple's household division of labour and their social networks, while the separate interviews explored respondents' individual perspectives on a number of themes, including decisions around conception, the significance (or not) of the biological and social relationships to their children, and the extent to which women felt their parental and familial relationships were recognised, supported and validated by others.

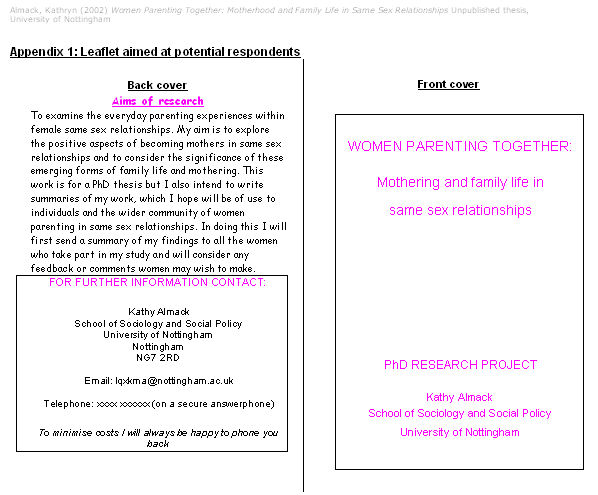

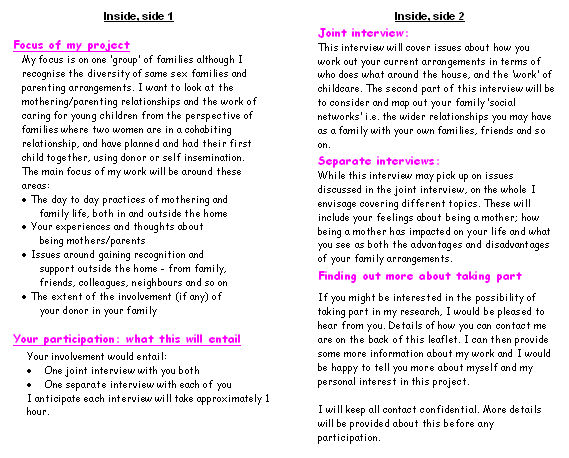

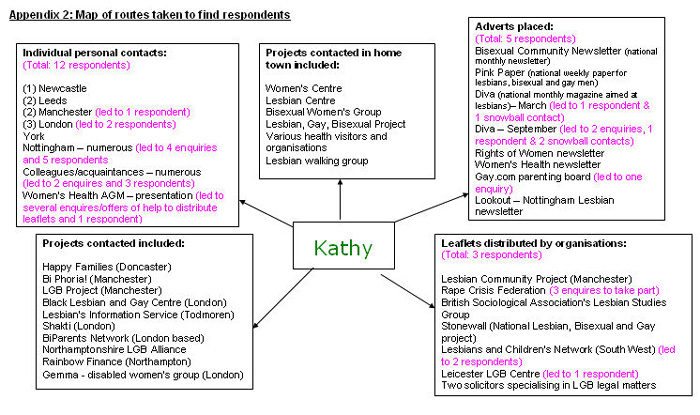

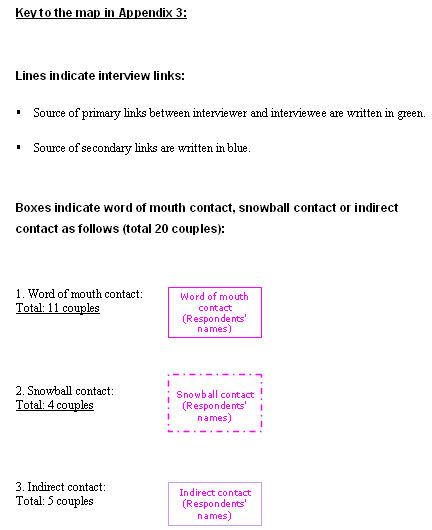

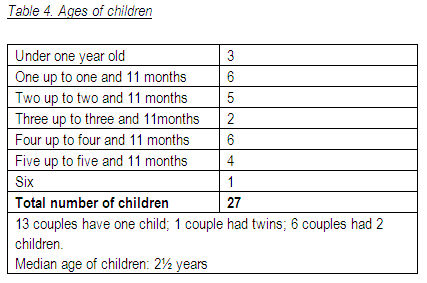

2.3 Out of the 40 women interviewed, I only knew one woman personally. I discuss issues of recruitment in later sections but see also appendices which provide further information. Appendix 1 shows the main publicity leaflet distributed about my project; Appendix 2 indicates routes through which I tried to access respondents and Appendix 3 maps out the successful routes of recruitment. Appendix 4 provides the sample profile. This brief summary of course obscures the complexities of a research project, the dilemmas and issues of, for example, recruitment, fieldwork, analysis and writing up; some of which I explore further in the rest of this article.

2.4 Early on in my doctoral studies I made the decision to not write myself into any 'public' accounts about my research. I do acknowledge that this raises particular dilemmas in writing an article in which I aim to address issues of how the researcher's identity and experiences may impact on the processes of doing research[2]. However I argue it is possible to open up such debates and produce a reflexive account without the need to provide a personal biography. Many researchers in the field of LGBT research do adopt the convention of stating their own sexual orientation possibly informed by the politics of coming out. However - as noted above in the examples of research into LBGT family lives, shared 'insider' status is often limited to the acknowledgement of a shared sexual orientation although there are many other facets of identity which may have an impact on aspects of the research project. Furthermore, as I discuss later, the research relationship is far more complex than the simple dichotomy of insider or outsider suggests.

2.5 I do not wish to contest the decision of researchers to reveal aspects of their identity or biography but also believe that researchers have a right to maintain a level of privacy if they wish to do so. This need not detract from the rigour of the research undertaken nor from the accounts written up about the research as amply illustrated by other sociological research accounts of a diverse range of family lives. Researchers are careful to guarantee anonymity to respondents. Indeed, ethical guidelines, such as those set out by the British Sociological Association (2002), emphasise the need to respect the privacy of those who participate in the research process these principles should also extend to researchers who, furthermore, do not have the benefit of anonymity afforded to respondents. Providing a mini biographical account to potential respondents (as I did) and putting this information into the public domain are two different considerations, with the latter less likely to stay within the control of the researcher. There is a further issue to consider in that the researcher's self-disclosure may also encroach upon the privacy of those around her/him, such as family members. As noted in the BSA ethical guidelines, 'decisions made on the basis of research may have effects on individuals as members of a group' and again, this may apply to researchers as well as respondents.

Access and recruitment: sampling and seeking out hidden populations

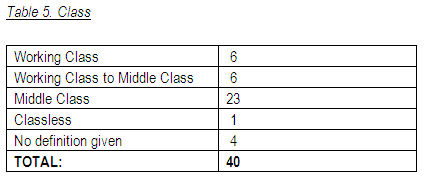

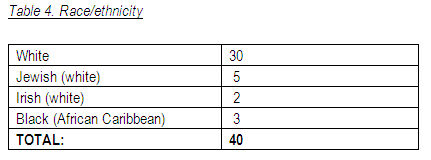

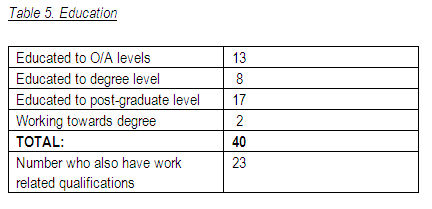

3.1 My starting point in accessing lesbian parent families (who 'fitted' within my criteria) was to use my own personal networks and those of friends, friends of friends and colleagues (as mapped out in Appendix 3). I also widely distributed a leaflet via a range of contacts (see Appendix 1 and 2). I had also hoped to use a 'snowballing' method[3], assuming that when I successfully recruited some respondents they would be able to put me in touch with other couples. While this is frequently cited as a common approach by other studies of LGBT lives (Browne, 2005), it was not a particularly successful approach in my study (I recruited 4 couples by this method).3.2 Ultimately recruitment of my sample proved to be a lengthy and time-consuming exercise. Many researchers have reported similar difficulties in finding LGBT respondents (Dunne, 1997, Heaphy et al., 1998, Heaphy, 2001) although some also suggest that sharing a similar identity with one's respondents is an asset in being able to tap into these 'hidden populations' (Plummer, 1981). Some researchers report drawing on their knowledge of existing LGBT networks examples of the latter include the use of lesbian mailing lists (Gabb, 2004); established lesbian groups (Farquhar, 1999); local or national LGBT press and groups (Heaphy et al., 1998). Heaphy et al. (1998) state that they tapped into different LGBT groups in an aim to capture different social and cultural positionings as well as a geographical mix. However use of existing networks can also lead to recruiting people who are most confident about being out and taking part in research and who are part of the most visible sections of LGBT communities. These are generally found in urban areas, and tend to consist of (mainly) middle class white educated respondents. Tapping into one's own networks may also promote a reliance on respondents who share similar networks to those of the researcher. These kinds of difficulties are often highlighted as a limitation by existing studies, but few have addressed the possibilities for broader recruitment (notable exceptions include Yip, 2005, Taylor, 2004).

3.3 However, in research on sensitive topics, word of mouth recruitment is often the most effective recruitment strategy available. This proved to be the case in my study. I recruited twenty couples over an eighteen month period. Fifteen couples were contacted via word of mouth methods and five by indirect methods (see Appendix 3, Almack, 2002). Many women commented that the key factor which influenced their decision to take part in my study was that a friend or colleague had contacted them about my research. Statements such as, 'X knew you and she said you were sound' were also common. This point relates to further issues of respondents 'checking out' who I was (cf. Duncan and Edwards, 1999) and what my aims and motivations were in doing this research, providing respondents with some reassurance that their own objectives (see section below) in taking part could be met. Such reassurances are particularly significant when the research is of a sensitive nature (Browne, 2005). I achieved some diversity in terms of recruiting a mix of respondents living in urban and rural areas (see Appendix 4, Almack, 2002 for further detail) and I also recruited couples who had no or limited contact with lesbian parent networks and communities. While there is some evidence of new 'non-heterosexual' narratives emerging, which are identified as a resource for developing new ways of living (Plummer, 1995, Weeks et al., 2001), access to these knowledges can not be taken for granted. Some of the respondents in my study had very limited access to information about 'doing family' as part of a same sex couple. As I discuss later, this can have implications on the stories accessed. Interestingly those recruited through my leaflet sent to a lesbian parenting network were among those most isolated in terms of knowledge of other lesbian parents (the parenting network formed part of their early attempts to try and tap into networks).

3.4 Sampling criteria and recruitment are often introduced without reference to the implications at later stages of the research, yet these stages can have consequences for the research stories accessed and told. Plummer (1995) discusses how community narratives are formed through stories that are told about them (this can include research narratives written up the researcher) and from stories that originate within (such as the respondents' narratives). I am conscious that my sample only represents one kind of lesbian parent family. This family form has sometimes been represented as particularly radical, representative of 'everyday experiments' (Giddens, 1992), and this becomes part of the community narratives circulating. Elsewhere I argue for the benefits and possibilities for separate explorations of different kinds of lesbian parent families and within this, the need to address the rich diversity of lesbian parent families (Almack, 2007).

3.5 At the same time my findings differ from other research accounts that have focused on a similar sub-section of their sample (i.e. those who conceived by insemination and who had children in the context of an openly same sex relationship Donovan, 2000, Dunne, 2000). For example, many of my respondents did not promote a view of themselves as living up to the community narrative of being a radical family form, rather presenting themselves, for example, as being the same as any other (heterosexual) family. A significant number did not know of other lesbian parent families and had not tapped into or formed part of community networks around same sex parenting. While I do not have space here to account for and explore these differences, part of the reason may be the ways in which I accessed and recruited my sample[4].

Self selection

3.6 I asked respondents what had motivated them to take part in my research[5]. Common reasons cited included seeking information about same sex parenting or helping to share such information for other lesbian couples planning to have children; a motivation to educate others and to help change opinions and attitudes. Some wanted to use the opportunity to process and think about issues in relation to their own family. Finding out why respondents are willing to be interviewed provides another dimension to the context of the interview and of the account produced. Heaphy (2001) discusses respondents' potential assumptions that they hold the same 'political agenda' as the researcher, which may influence the accounts they give to a researcher and from which researchers draw conclusions. For example, respondents may want to present a positive public account of their family life, leading to the concealment of aspects of their lives which did not 'fit' with this picture. I agree with Heaphy that this does not necessarily invalidate accounts. It becomes another dimension to take into consideration and as such, it needs to be taken on board in addressing the relationship between lived lives and research stories.

3.7 Equally important are reasons why potential respondents do not want to take part, although of course these can be harder to find out about. In my research, from initial contacts made by intermediaries that I was aware of, I had some information fed back to me when couples did not want to take part. Two couples did not feel confident enough about 'being out' to take part, and in two other cases only one partner in the couple wanted to take part. Another couple, approached on my behalf, felt unable to take part because of problems within their relationship. They subsequently separated during the course of my research. This highlighted the fact that I was only likely to gain access to couples whose relationship and parenting arrangements are relatively stable and unproblematic. It is also possible that people I approached to ask them to contact couples on my behalf, acted as 'gatekeepers'[6] and may have done some of their own screening as to who they approached for me.

3.8 I was mindful that all of these incidences would have a bearing on the subsequent data. For example, as Edwards et al. (1999) argue, if people exclude themselves from research projects because they feel they cannot present positive or 'successful' accounts of their family lives, this can have implications for the sorts of stories that can be accessed and told. Farquhar (2000) raises a further dimension to these considerations. She argues that the silencing of debates on about violence in lesbian relationships suggests that lesbians may have a high level of investment in maintaining positive images of lesbian relationships. I do not want to suggest that any woman who refused to take part in my study was in a violent relationship but Farquhar's point connects to questions about wider investments in, for example, lesbian couples maintaining idealised constructions of lesbian parenting. As she suggests:

The desire to maintain a positive image of lesbianism and to minimise dissonance between disseminated ideals and lived realities, may lead lesbians ( ) to disguise relationships which fail to meet this ideal (2000:229).

3.9 Thus, reasons for not taking part, whatever they may be, can alert researchers to 'absences' within the samples accessed, and thus to potential 'silences' within accounts written up.

The interview setting

Insider/outsider debates and developing rapport

4.1 As noted earlier, some researchers in the field of LGBT research have discussed the advantage of being an 'insider' in terms of sexual orientation in the interview situation. Such claims are made in relation to gaining the trust of respondents, which in turn assists the development of rapport in the interview setting (Dunne, 1997), and in relation to being familiar with the social world being investigated (LaSala, 2003).4.2 Heaphy et al., (1998) acknowledge that the existence of perceived commonalities on the grounds of sexual orientation can be over-stated but do not discuss ways in which this may have played out in the interview setting. Browne (2005:55) further explores this point. She contends that although her identity as a non-heterosexual woman was salient in developing trust with her participants, 'categories such as sexual orientation may not be adequate in understanding complex research relations'. She discusses how friendships between participants (and her friendships with participants) informed the accounts she accessed a willingness for example to share information 'amongst friends' that might have been withheld in front of strangers. However she also notes that friendships may have constrained her data collection at times for example where women were reluctant to express views that might hurt a friend's feelings.

4.3 In relation to assumptions of shared cultural understandings, other researchers in the field of LGBT research identify the ways in which an 'insider' status may have both advantages and disadvantages (Valentine, 2002, LaSala, 2003). LaSala (2003) suggests that LGBT researchers may have special knowledge and shared understandings with their respondents which can enhance data collection via the development of empathy and having the 'insider' knowledge necessary to develop appropriate interview questions. He argues, for example, that as a gay man he is aware of the subtle ways that parents might fail to recognise or acknowledge their son or daughter's same sex relationship, and this understanding enabled him to develop appropriate questions to explore this area. However, he also acknowledges that 'inside' investigators may assume common understandings and thus fail to fully explore a respondent's perspective. In a similar point, Kong et al. (2002) go further and question whether researchers should be part of the communities they study. They suggest this may work to obscure rather than discover knowledge. However these debates rarely problematise the notion of the insider status per se.

4.4 Claims made by some LGBT researchers in relation to having an insider status are somewhat reminiscent of earlier feminist assumptions that commonalities such as gender or sexual orientation are homogenous categories that provide a basis to mediate access and rapport and, by implication, to access 'good quality' data, in a relatively unproblematic way. The advantages of researcher and respondents having a shared identity have been widely debated in terms of gender by feminist researchers[7]. Some of the earliest writing of second wave feminist research (such as Oakley, 1981) argue that women researchers enjoy the advantages of having an 'insider' status when interviewing other women.

4.5 Later debates in feminist methodology and in other fields such as anthropology highlight the complex social positionings of researchers and respondents, which challenge the dichotomy of being an insider or an outsider (Edwards and Ribbens, 1998, Sherif, 2001) and can add to existing understandings within LGBT methodology debates. These discussions highlight ways in which the notion of being an insider or an outsider is never as straightforward as it may first appear. For each individual there may be a range of significant factors that structure the differences between the researcher and the respondent in ways that make the researcher an 'outsider' to the respondent's experiences and vice versa. Sherif (2001) illustrates this well in her discussion of being a 'partially indigenous' female researcher conducting fieldwork with Muslim families in Cairo. She identifies a range of different social identities she occupied - as an American graduate student, an Egyptian daughter, a single women in her late 20s and a trained anthropologist. She experienced the boundaries between being an insider and/or an outsider as complex and constantly shifting, depending on whom she was with and which part of her identity she presented to whom.

4.6 Undertaking research per se may also set one apart from the phenomenon or social world being investigated. For example, Edwards and Ribbens (1998) discuss Ribbens' experience of studying the social networks of mothers with young children. She had experienced feeling an insider within such networks but entering these networks as a researcher and learning ways to present this social world to an academic audience set her apart as an outsider. As these examples illustrate and as noted by Griffith (1998), the interaction of one's biography and social location shape the research relationship in multifaceted ways highlighting how the insider/outsider status is contextual and fluid.

Reciprocity: sharing information

4.7 Sharing information can work in both directions. At the first point of direct contact with women, I outlined a brief biography about myself and my motivation for doing this research. This alone also allows each respondent to form their own opinions of where they may 'place' the researcher in terms of the insider/outsider status perhaps noting commonalities and differences in the researcher's biography and social location in relation to their own. All the women I spoke to were happy to go forward and take part in my research study. I noted earlier how some respondents 'checked me out' via word of mouth contacts. Some respondents were more curious than others to know more about me and asked me further questions at this point or in the interview setting. In the interview setting, these types of conversations took place before, between and/or after the interviews. I did not enter into conversations during the interview - respondents rarely asked me for information about myself in this setting. In a discussion about reciprocity, Ribbens (1989) argues that to talk about oneself (as the researcher) during the interview can be seen as 'breaking the research contract' where the focus is on the respondent who has:

Permission to do what is normally seen as indulgent and socially reprehensible: to talk about oneself at great length (1989:584).

4.8 Several of my respondents commented that the most enjoyable aspect of taking part in the research was precisely this - the opportunity to talk about themselves. As one respondent commented 'the good thing about being interviewed is that you talk 'to' some-one rather than 'with' that person'.

4.9 Reciprocity in the interview setting has been discussed in depth, particularly within feminist methodology, as a way to reduce exploitative power imbalances between researcher and respondent, and to develop rapport with respondents. Ribbens (1989) discusses different levels of reciprocity. One level relates to how the researcher responds to questions she is asked; she argues that while we are able to choose how much we wish to disclose this rarely leads us to the same level of exposure that we ask of our respondents. At another level, Ribbens argues that to be open about ourselves can impact significantly on what respondents reveal during the interviews. She highlights a danger that such reciprocity may inveigle respondents into revealing more than they had perhaps intended. Finch (1984), who felt that her respondents needed to know how to protect themselves (in order not to reveal too much) from her, in the interview situation, makes this same point.

4.10 I am not convinced that women I interviewed could be so easily duped into revelations they did not want to make and it is important to recognise respondents do make choices about what they reveal. In any research project it is possible that a different researcher may access different stories to those that are accessed but the dynamics of what is and isn't told to the researcher and the ways in which these accounts are shaped are complex. During my research 'silences' were sometimes made explicit (but equally there may be other situations where information was not disclosed and I was not aware of this). For example, in one set of interviews, one woman told me about a temporary separation in the couple's relationship following the birth of their first child. This was not raised in the other two interviews but when we all came together before I left, this woman's partner found out that I had been told about the temporary separation and responded, 'How embarrassing, I thought we weren't going to talk about that'. Another couple told me they had decided they would not talk to me in any detail about their donor and the difficulties they had experienced within this relationship, saying: 'We know it would probably be helpful for your research to know about (the donor) but we feel it is better for us that we don't tell you'. It was still a sensitive issue and there was a court case about it coming up. As researchers we can never be sure how much of the story is or is not revealed, at most we should only expect to gather partial narratives. What respondents chose to tell us is always selective regardless of how they might perceive the researcher. Gilgun et al. (1992:4) suggest that when interviewing different members of a family group, secrets and loyalties will remain inaccessible to us. However, they also argue that being alert to limitations such as these can provide an insight into the ways in which boundaries are defined and maintained in families. Thus they are an equally rich source of data.

Issues of interpretation and validity

5.1 De Vault (1999:85) argues that the debates about the researcher's positioning in relation to achieving access and developing rapport and reciprocity are only the beginning. She suggests that there are other important considerations concerning the researcher's identity which are less commonly integrated into the analysis, interpretation and writing up of research. These issues have been taken up within feminist methodology, particularly in relation to how researchers address the boundaries of their own lived experiences, their research explorations of the private lives of others and the writing up of public academic accounts debates which are useful and central to research where these boundaries may be particularly 'loose and permeable' (Edwards and Ribbens, 1998:203).5.2 Griffith (1998) asks if the biography of the researcher privileges or disqualifies their knowledge claims. She highlights the dangers of assumptions that researchers who have a 'lived familiarity with the group being researched' have greater claims to epistemological privilege. Others (such as Edwards, 1993, De Vault, 1999, Reinharz and Chase, 2002) have similarly questioned the assumption that 'gender' or 'sexual orientation' are homogenous categories and that 'matching' of researcher and respondent along these lines will necessarily result in the production of more authentic research accounts. Such assumptions overlook the heterogeneity of experiences that go beyond gender or sexual orientation and which are mediated by the experience of class, race, ethnicity, and disability, as well as other factors which might include parenthood, political affiliations and so on. Reinharz and Chase (2002) suggest that these more recent feminist debates bring a welcome complexity to reflections on the diversity of researchers' and respondents' social locations and subjectivities. They discuss the example of research into women's experiences of motherhood by (female) researchers who are not mothers, and they highlight researchers' different conclusions about the ways in which being 'non-mothers' impacted on their work.

5.3 Griffith and Smith (1987) highlight ways in which their personal histories as mothers also became a resource for analysis. Griffith's field-notes, for example, detailed her emotional reaction to one interview she had carried out, which made her feel her own mothering had been inadequate. Griffith and Smith demonstrate how these kinds of personal reactions can go beyond being part of the interview dynamics and be utilised to enrich the subsequent analysis. Griffith's reflections on her experience in a particular interview setting alerted them to the 'moral dimension' of mothering and the social constructions of 'good'/'bad' mothering. They then employed this recognition to look for other illustrations of this dimension to mothering in other accounts. Doucet (1998) highlights other ways in which aspects of the researcher's personal experience can impact on the analysis. For example, she suggests she was drawn to make sense of her data within a theoretical framework that debated the complexities of 'care' and 'care-work' precisely because she was so deeply involved in care-work herself. However, she also observes that 'I did not realise it at the time (but) my life was almost completely taken up with caring and writing about caring' (1998:53). Thus while she provides a lucid account about the impact of her own experiences of motherhood on her analysis, her account also highlights that to some extent we may only see these kinds of processes at play with the benefit of hindsight.

5.4 As Edwards and Ribbens argue:

We need high standards of reflexivity and openness about choices made throughout any empirical project, considering the implications of practical choices for the knowledge being produced' (Edwards 1998:4)

5.5 In debates about the subjective, interpretative nature of research, feminists have argued that the production of knowledge is a social activity which is culturally, socially and historically embedded thus resulting in 'situated knowledges' (Haraway, 1988). In recognition of this, Harding (1992) recommends an explicit and systematic examination and account of our biases, beliefs and social locations. Mauthner and Doucet (1998) have subsequently pointed out the difficulties in achieving this, not least because it requires a profound level of self-awareness that few of us possess. Holland and Ramazanoglu (1994:145) similarly highlight the social nature of interpretation and suggest that 'some form of openly reflexive interpretation then seems essential if we are to claim any validity for our conclusions'. However, they also acknowledge that such aims are not always, if ever, reached in practice. Stanley and Wise (1993:177) additionally observe that researchers should be cautious about the extent to which they reveal themselves within the final account, not least because 'to locate oneself within research and writing is a hazardous and frightening business'.

5.6 While I agree with the central tenets of reflexivity (in so far as this is possible), there are no easy solutions to the issues raised. Furthermore we do not always have the luxury of time or space to write up detailed methodological accounts of our research. Finally, these discussions touch upon the extent of self-disclosure the researcher is prepared to incorporate into the writing up of the research. In addition to debates about how much we reveal about ourselves to respondents there are issues about how much we are prepared to reveal about ourselves in public accounts of our work in claiming validity for our conclusions. While there is very little literature that considers the impact of self-disclosure in the interview situation, there is even less that considers self-disclosure when writing up and publishing our work. Edwards and Ribbens (1998) offer a rare account of these dilemmas. They note that researchers do not have the protection of anonymity that is offered to research participants and suggest that researchers have decisions to make about what to put in and what to leave out, in terms of self revelations, when writing up our research (1998:204).

Conclusion

6.1 In this article I identify and discuss some of the complexities of doing and writing up research, with a particular emphasis on my experience of a study into the lives of lesbian parent families and accounts of other researchers carrying out qualitative research exploring the lives of LGBT people. In a consideration of methods of recruitment and subsequent interactions with respondents, I question the extent to which the notion of an insider identity makes these processes easier and/or more valid, and also highlight the fluidity of boundaries between being an insider or an outsider. We can 'list' who we are in terms of sexual orientation (and also class, gender, disability, age and so on) but there are many other aspects of the researcher and respondents' biographies which may play a part in the access and recruitment of respondents and in the research interaction with respondents. As Valentine (2002:120) notes 'dualisms such as insider/outsider can never (quite) capture the complex and multi-faceted identities and experiences of the researcher' (or respondent). The notion of shared identities can also obscure crucial questions, about how and where to recruit, who comes forward to do the research and to take part as respondents in research and who gets missed out; questions which need to be revisited.6.2 Beyond decisions about sampling criteria, methods of recruitment and the process of doing fieldwork, there are also other ways in which the researcher shapes the whole research process, through their research agendas, analytical approaches and so on. The researchers' own narratives further contribute to the outcomes of research. These narratives include those that researchers may tell to respondents - about their personal lives or about motivations for doing the research alongside the narratives formed through the social interactions of the interview setting. Furthermore, researchers have the 'interpretative authority' which shapes the way in which respondents' narratives are written up and published - presented in the public domain.

6.3 Thus I have sought to acknowledge the influence of the researcher while also raising questions about the extent to which researchers need to be explicit about their own biographies. Providing any kind of biographical account does not necessarily lead to a reflexive account. The critical issue is to reflexively trace and document decisions and processes along the way as far as the researcher can be aware of these, as Mauthner and Doucet note:

We need to document these reflexive processes, not just in general terms such as our class, gender and ethnic background; but in a more concrete and nitty-gritty way in terms of where, how and why particular decisions are made at particular stages (Mauthner and Doucet 1998:138).

6.4 And at the same time the researcher needs to consider what they do or do not want to reveal about their own lives. I argue it is possible to provide a reflexive research account without having to put personal information into the public domain. It remains for the reader to decide how frustrating or successful I have been in this respect (and see endnote 2). In the process of moving from private lives (in terms of the researcher and respondents' accounts) to public knowledge, these considerations are particularly salient where the researcher has some level of personal investment in the topic being researched (Edwards and Ribbens, 1998).

6.5 In claiming validity for our conclusions these are key issues but there are no easy answers as to how we document these processes. It raises questions about the space and time we have to write these up alongside our research accounts, the extent to which we are able to be 'transparently' reflexive (Lohan, 2000) and the extent to which we want to maintain our own privacy (as we so assiduously maintain the anonymity of our respondents). Rather than providing any definitive conclusions. I have sought to contribute to discussions about and recognition of these dilemmas.

Appendices

|

|

|

Appendix 4

|

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the women who took part in my research project. Many thanks to the reviewers and Andrew Yip for their comments.Notes

1 Such accounts have subsequently been published (see, for example, Almack, 2005, Ryan-Flood, 2005).2As one reviewer noted, it can leave personal information implicit and open to interpretation depending on the reader. However - I have always been more open to such discussions in the context of face to face contact where one has more ability to, for example, judge the motivations of people wanting to know more information about one's biography/identity

3 I distinguish here between drawing on friends of friends or colleagues of friends and so on, to put me in touch with potential respondents and 'snow-balling' which I define as a means whereby the researcher relies on respondents interviewed to introduce the researcher to other potential respondents.

4 Gabb (2004) discusses differentials in lesbian parent studies and accounts for some of these differentials in terms of how researchers sampled and recruited to their studies.

5 Peel et al. (2006) discuss how eliciting this information at different points during data collection can make a difference although this point is perhaps more relevant to longitudinal studies than those conducting one-off interviews.

6 See Emmel et al. (2006) for a wider discussion of a range of strategies to recruit people from 'hard to reach' or socially excluded communities, which includes the issue of gate-keeping.

7 Earlier debates are evident in classic fieldwork discussions such as Merton's paper (Merton, 1972) on the advantages and disadvantages of having an insider/outsider status in relation to the group being studied.

References

ALMACK, K. (2002) "Women Parenting Together: Motherhood and Family Life in Same Sex Relationships" Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. <http://etheses.nottingham.ac.uk/archive/00000268/01/Almack_-_Women_Parenting_Together.pdf> (accessed Jan 2008).

ALMACK, K. (2005) "What's in a Name? An Exploration of the Significance of the Choice of Surnames Given to the Children Born Within Female Same Sex Families", Sexualities, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp.239-254.

ALMACK, K (2007) "Out and about: Negotiating the Process of Disclosure of Lesbian Parenthood", Sociological Research Online, Vol. 12, No. 1, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/1/almack.html> (accessed Jan 2008).

BRITISH SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (2002) Statement of ethical practice for the British Sociological Association. <http://www.britsoc.co.uk/equality/Statement+Ethical+Practice.htm> (accessed, January 2008).

BROWNE, K. (2005) "Snowball Sampling: Using Social Networks to Research Non-heterosexual Women", International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 47-60

DE VAULT, M. (1999) Liberating Method: Feminism and Social Research. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

DONOVAN, C. (2000) "Who Needs a Father? Negotiating Biological Fatherhood in British Lesbian Families Using Self-Insemination", Sexualities, Vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 149-164.

DOUCET, A. (1998) "Interpreting Mother-work: Linking Methodology, Ontology, Theory and Personal Biography", Canadian Women's Studies, Vol. 18, Nos. 2 & 3, pp. 52-58.

DUNCAN, S. and EDWARDS, R. (1999) Lone mothers, paid work and gendered moral rationalities. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

DUNNE, G. A. (1997) Lesbian Lifestyles: Women's Work and the Politics of Sexuality. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

DUNNE, G. A. (2000) "Opting into Motherhood: Lesbians Blurring the Boundaries and Transforming the Meanings of Parenthood and Kinship", Gender and Society Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 11-35

EDWARDS, R. (1993) "An Education in Interviewing: Placing the Researcher and the Research", in C. Renzetti, and R. Lee (editors) Researching Sensitive Topics. London: Sage.

EDWARDS, R. and RIBBENS, J. (1998) "Living on the Edges: Public Knowledge, Private Lives, Personal Experience". in J. Ribbens, and R. Edwards (editors) Feminist Dilemmas in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

EDWARDS, R. RIBBENS, J. with GILLIES, V. (1999) "Shifting Boundaries and Power in the Research Process: the Example of Researching 'Stepfamilies' in J. Seymour and P. Bagguley (editors) Relating Intimacies: Power and Resistance. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

EMMEL N., HUGHES, K. and GREENHALGH, J (2006) "Methodological Strategies to Recruit and Research Socially Excluded Groups" End of Award Report to the Economic and Social Research Council <http:www.esrcsocietytoday.ac.uk/ESRCInfoCentre/ViewAwardPage.aspx?AwardId=2615> (accessed Jan 2008).

FARQUHAR, C (1999). "Are Focus Groups Suitable for Sensitive Topics?" In R. Barbour and J. Kitzenger (editors) Developing Focus Group Research. London: Sage.

FARQUHAR, C. (2000) " 'Lesbian' in a Post-Lesbian World? Policing Identity, Sex and Image", Sexualities, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 219-236.

FINCH, J. (1984) " 'It's Great to Have Someone to Talk To': The Ethics and Politics of Interviewing Women" in C. Bell and H. Roberts (editors.) Social Researching: Politics, Problems, Practice. London: Routledge, Kegan and Paul.

GABB, J. (2004) "Critical Differentials: Querying the Incongruities Within Research on Lesbian Parent Families", Sexualities, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 167-182.

GIDDENS, A. (1992) The Transformation of Intimacy Cambridge: Polity Press.

GILGUN, J.F., DALY, K. and HANDEL, G (1992) (editors) Qualitative Methods in Family Research. London: Sage.

GRIFFITH, A. (1998) "Insider/Outsider: Epistemological Privilege and Mothering Work", Human Studies, Vol. 21, pp. 361 376.

GRIFFITH, A. and SMITH, D. (1987) "Constructing Cultural Knowledge: Mothering as Discourse" in J. Gaskell and MacLaren, A (editors) Women and Education: A Canadian Perspective. Calgary, Alberta: Detselig.

HAIMES, E. and WEINER, K. (2000) " 'Everybody's got a Dad' Issues for Lesbian Families in the Management of Donor Insemination", Sociology of Health and Illness, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 477-499.

HARAWAY, D. (1988) "Situated Knowledges: the Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective", Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 575-599.

HARDING, S. (1992) Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

HEAPHY, B. (2001) Who Counts? 'Inclusion' in Research With Lesbians and Gay Men, paper presented to Researching Under The Rainbow: The Social Relations of Research with Lesbians and Gay Men Lancaster University, September 2001.

HEAPHY, B., WEEKS, J. and DONOVAN, C. (1998) " 'That's Like My Life': Researching Stories of Non-Heterosexual Relationships", Sexualities, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 453-470.

HOLLAND, J. and RAMAZANOGLU, C. (1994) "Coming to Conclusions: Power and Interpretation in Researching Young Women's Sexuality" in M. Maynard and J. Purvis (editors) Researching Women's Lives from a Feminist Perspective. London: Taylor and Francis.

KONG, T. S. K., MAHONEY, D. and PLUMMER, K. (2002) "Queering the Interview" in J. F. Gubrium, F. Jaber and J. Holstein (editors) The Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Methods. London: Sage.

LASALA, M. C. (2003) "When Interviewing 'Family': Maximising the Insider Advantage in the Qualitative Study of Lesbians and Gay Men" in W. Meezan and J. I. Martin (editors) Research Methods with Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Populations, New York: Harrington Park Press.

LOHAN, M. (2000) "Come Back Private/Public: (Almost) All Is Forgiven: Using Feminist Methodologies in Communication Technologies" Women's Studies International Forum, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 107-117.

MAUTHNER, N. and DOUCET, A. (1998) "Reflections on a Voice-centred Relational Method: Analysing Maternal and Domestic Voices" in J. Ribbens and R. Edwards, (editors) Feminist Dilemmas in Qualitative Research: Public Knowledge and Private Lives. London: Sage.

MERTON, R. K. (1972) "Insiders and Outsiders: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge" American Journal of Sociology Vol. 78, July 1972 - May 1973, pp. 9-47

OAKLEY, A. (1981) "Interviewing Mothers: A Contradiction in Terms" in H. Roberts (editor) Doing Feminist Research. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

PEEL, E., PARRY, O., DOUGLAS, M., and LAWTON, J. (2006) " 'It's No Skin off My Nose': Why People Take Part in Qualitative Research" Qualitative Health Research Vol. 16 (Dec), pp. 1335 1349

PLUMMER, K. (1981) (editor) The Making of the Modern Homosexual. London: Hutchinson.

PLUMMER, K. (1995) Telling Sexual Stories. London: Routledge.

REINHARZ S. and CHASE, S. E. (2002) "Interviewing Women" in J.F. Gubrium and J.A. Holstein (editors) The Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Methods. London: Sage Publications.

RIBBENS, J. (1989) "Interviewing Women: An 'Unnatural Situation'?" Women's Studies International Forum, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 579-592.

RYAN-FLOOD, R.. (2005) "Contested Heteronormativities: Discourses of Fatherhood among Lesbian Parents in Sweden and Ireland, Sexualities, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 239-254..

SHERIF, B. (2001) "The Ambiguity of Boundaries in the Fieldwork Experience: Establishing Rapport and Negotiating the Insider/Outsider Status" Qualitative Inquiry Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 436 447.

STANLEY, L. and WISE, S. (1993) Breaking Out Again: Feminist Ontology and Epistemology. London: Routledge (First Edition published as Breaking Out in 1983).

TAYLOR, Y. (2004) "Negotiation and Navigations An Exploration of the Spaces/Places of Working Class Lesbians, Sociological Research Online, Vol. 9, No. 1. <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/9/1/taylor.html> (accessed Jan 2008).

VALENTINE, G. (2002) "People like us: negotiating sameness and difference in the research process", in P. Moss (editor) Feminist Methodologies. Oxford: Blackwell.

WEEKS, J., HEAPHY, B. and DONOVAN, C. (2001) Same Sex Intimacies: Families of Choice and Other Life Experiments. London: Routledge.

YIP, A. K. T. (2005) "Religion and the Politics of Spirituality/Sexuality", Fieldwork in Religion. Vol. 1, No. 3. pp. 271 289.