Reflexivity and Researching National Identity

by Robin Mann

University of Oxford

Sociological Research Online, Volume 11, Issue 4,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/4/mann.html>.

Received: 7 Jun 2006 Accepted: 8 Dec 2006 Published: 31 Dec 2006

Abstract

This article focuses on the reflexive dynamics of interviewing in the context of a recent qualitative investigation of ethnic majority views of national identity in England. There is now an established literature which specifies the routine mobilisations of national identity through the course of everyday social interaction. Discourse studies also have been centrally concerned with the interview-as-topic and there is considerable work here on ethnic and racial categorizations within the interview context. Taking such work as its departure point, this article will illustrate how and why the interviewer also matters in talking about national identity. While the role of the interviewer is increasingly acknowledged in qualitative research, there has been little attempt to consider this particular methodological dilemma in nationalism research. In highlighting this problem, this article argues in favour of a more reflexive approach to the study of nationalism and national identity, one which brings to bear the researchers' own unwitting assumptions and involvement.

Keywords: English/British, Complicity, Discourse, Interviewer, Interviewing, National Identity, Reflexivity

Introduction: National Identity and the Everyday Lifeworld

1.1While scholarship on nations and nationalism has by and large been macro-analytical in its approach, recent trends in the field of study have led to a greater focus upon national identity at the individual level, drawing particular attention to the ways in which ordinary people, the presumed recipients of nationalist ideologies, construct national identity through both discourse and social interaction. There is now a growing body of qualitative interviewing and ethnographic research, which specify national identities as social identities which are constructed and negotiated at the local or everyday level (Bechhofer et al 2000, de Cilla et al 1999, Condor 2000, Condor & Abell 2005, Day & Thompson 1999, Fox 2004, Hester & Housley 2002, Jacobsen 1997, McCrone 2002).1.2 Day & Thompson (1999) provide the case for the local production of Welsh identities. They examine the 'common-sense' modes of talking about national identity and view of nationalism as a 'naturalizing' discourse whereby belonging to a 'nation' comes to be seen as something natural and unavoidable. They refer to the 'factuality' of national identity (1999:32). As Hester & Housley state, 'for whatever reason, national identity enters into social life in hitherto largely taken for granted ways' (2002:11). National categories thus, like other social categories, form part of a common stock of knowledge (Berger & Luckmann, 1967), part of the 'lifeworld' (Habermas, 1987) from which people come to share sense of who 'we' are. Research forming part of the 'Edinburgh National Identity Group' (Bechhofer et al 2000, Kiely et al 2001, McCrone et al 1998, McCrone 2002) has also been concerned with national identity as negotiated through the course of everyday social interaction. They point to contexts, such as the Scottish-English border and in-migrants in Scotland, where national identity, far from taken for granted, is highly problematic. This research suggests that it is within such contexts that the constructed, situational and negotiated nature of national identity is more obviously revealed (although constructions of the nation as taken for granted can be no less the outcome of social interaction than its problematised negotiation).

1.3 By stressing the need to specify, rather than assume, how individuals position themselves in relation to national identity, these studies make an important contribution to knowledge by re-thinking the level of analysis from the macro to the micro. This not only adds to our knowledge of nations and nationalisms as a whole but brings national identity into the wider sociological concern with the construction of social identities within everyday interaction. Yet this point has not always gone so far as to consider the interview as a particularly reflexive form of interaction and to acknowledge the active role of the interviewer in co-producing how national identity is talked about within the interview. This is an important consideration because if individuals do see the criteria they use to categorise others to be commonly accepted or widely shared, then they may also view these criteria to be accepted by the interviewer as well. As such, how individuals talk about national identity cannot be divorced from the interviewers (non-)interventions as part of the interview context. This article wishes then to contribute to this body of literature by providing a reflexive analysis of interview research carried out as part of a recent qualitative study of national identity in England.

1.4 An important contribution to this shift towards 'everyday' in the study of nations and nationalism is provided by Michael Billig's Banal Nationalism (1995). Through his focus on the banal, Billig (1995) argues convincingly that nationalism is not only something that exists primarily at the margins or peripheries of modern states but at their core as something commonplace to everyday life with Western democracies. Billig draws our attention to the way in which individuals come to think of themselves as 'national' in a relatively unproblematic way, and also that this process tends to go unnoticed 'for it is part of the common-sense imagining of "us"' (1995). What has not been so equally acknowledged however, is the methodological dilemma that banal nationalism raises for the scholar:

Because nationalism has deeply affected contemporary ways of thinking, it is not easily studied. One cannot step outside the world of nations, and now rid oneself of the assumptions and common-sense habits which come from living within the world. Analysts must expect to be affected by what should be the object of their study (Billig, 1995:37).

1.5 The above statement suggests a need for scholars to adopt a more reflexive approach to the study of nationalism and national identity, and to pay greater attention to the positioning of the researcher/analyst in relation to this object of study. Of course, simply highlighting reflexivity and co-production is to say nothing that isn't already considered as methodological staple for sociological research generally. Yet there has been little attempt to consider this dilemma in nationalism scholarship and in relation to its specific dimensions[1]. As Brubaker (2004) also argues, despite the near universal acceptance of social constructivist approaches to ethnicity in the social sciences, greater attention needs to paid to how ethnic, national and racial categories are used by analysts themselves. As he states:

the problem is that "nation", "race", and "identity" are used analytically a good deal of time more or less as they are used in practice, in an implicitly or explicitly reifying manner, in a manner that implies or asserts that "nations," "races," and "identities" "exist" as substantial entities and that people "have" a "nationality", a "race", an identity (Brubaker, 2004:32-33).

1.6 This article then wishes to deal reflexively with these problematic boundaries between researcher and her/his membership of, and positioning in relation to, the field of study. How does the analyst use these categories in the practice of interviews? In the context of interview research on national identity, not only might the interviewers talk betray 'assumptions' and 'common sense habits', but respondents may also talk about their national identity as if shared with the interviewer. This suggests there may be general methodological issues which are peculiar to national identity. I wish to probe this further by examining why it is important to include the interviewers talk in the presentation of data and to illustrate, through drawing on extracts, why the interviewer also matters in talking about national identity. In highlighting this problem, this article argues in favour of a more reflexive approach to the study of nationalism, one which brings to bear the researchers' own unwitting assumptions and involvement.

'Race', 'Nation' and Discourse-analytical Approaches to the Interview

2.1 Of course, such a concern with the interview-as-topic has been longstanding in discourse studies. Stemming from Tajfel (1978) there has been an interest amongst social and discursive psychologists in the content and organisation of 'talk' within interaction. This has led to an interest in impression management within interview encounters as a topic for research. This research focuses on the discursive tools available to people in maintaining their own reasonableness, and avoiding the stigma of prejudice. Many of these studies have occurred primarily with 'race talk' in mind (Billig 1988; Van Dijk 1987, Van den Berg et al 2004; Wetherell & Potter 1992). It is widely accepted within these approaches that the research interview is 'jointly produced by the participants, and that the interviewer is as involved in the production as the interviewees' (Van den Berg et al 2004:3). Taking account of the researchers' role within interview interactions provides a way of analysing the situational and contextual contingencies of discourses around highly controversial or disagreeable themes. Often for example the researcher or interviewer is faced with a number of situated options when encountering 'race talk'. On one hand, interviewers may wish to contest particular views or comments made by the respondent which they find offensive so as to avoid complicity. On the other hand this option may conflict with a desire to produce considerate reactions with respondents who have been hospitable enough to welcome you into their homes. As Koole (2003:178) identifies, this is a particularly precarious dilemma in that it is often through expressing agreement with the content of the respondent's views that rapport is established. As such, attending to the interactions between interviewer and interviewee provides ways of examining how these dilemmas may be negotiated.2.2 Condor (2000) however demonstrates how this framework can also be applied to talk about 'the nation', to a concern with 'how ordinary speakers themselves deploy and interpret national references in the course of interaction' (2000:179). A key point here is that the taken-for-grantedness of national identity should be seen as a 'local interactional accomplishment' rather than an 'a priori fact' (2000:179). People will unproblematise national identity through discourse. But Condor also shows how further probing by the interviewer can reveal more ambiguous responses in which national identity for the respondent becomes a 'normatively accountable matter-of-prejudice' (2000:181). Hesitancies, false starts and pauses in the organisation of talk are attributed as evidence of national identity as a 'problematic topic' (2000:182). So while national identity is taken for granted by many, it is possible for this to become unhinged through further probing within social interaction. This suggests the need for interviewers/researchers to be particularly aware of the need to probe further the assumptions about national identity made by the respondent. These might include probings around their own 'straightforward' claims to national membership, about what defines the national boundary and any implicit knowledge about who is and who is not a member.

2.3 Although concerned primarily with majority views of racism and prejudice rather than matters of national identity, Verkuyten (1998) also adopts the conversational and interactive approach through focusing on how people talk to each other within their groups. Certainly, by shifting the attention to how people talk with each other, rather than with an interviewer, Verkuyten (1998) is able to recognise agency in a more constitutive way through drawing attention to the challenges and contestations that are made within conversations. A similar outcome is found with Tyler's (2004) ethnographic study of a former mining town in which her 'white' co-conversationalists frequently questioned and critically reflected upon other peoples' racist views.

2.4 Both discourse analysis and conversation analysis have the convention of both transcribing and presenting text in a particular way, according to the 'Jefferson System' (Atkinson, 1984), which is seen to do justice to its interactional and organisational specificity. Although such technicised conventions were not adopted for the purposes of this research, the author shares the importance of treating and presenting interviews as a form of interaction as well as acknowledging the interviewees talk as a collaborative construction in which the interviewer is always involved.

The Research

3.1 This article draws on a research project examining the ethnic majority in Britain, funded by the Leverhulme Trust[2]. Central to this research was to provide a purposive study of the ethnic majority and its dispositions towards national identity, social class and multicultural Britain. It was specifically concerned with extrapolating the inter-connections between everyday discourses of nation and class. As such, one of the key aims of the interviews was to encourage people to reflect upon their own sense of national identity, or the idea of having a national identity, and it is this topic that I will be examining here. In total, 100 individual in-depth interviews were conducted across two research sites, a small town and selected wards in Bristol. In what follows, I have selected 7 extracts from this corpus of interviews for the purposes of analysis. These have been selected in order to indicate the interactional nature of interviews and the constitutive role of the interviewer. As such these should be seen, following the ethnomethodological guise, as 'specific occasions' (Hester & Housley, 2002:11) of the 'here' and 'now', rather than as instances which are necessarily representative of a larger number of cases and contexts.3.2 This analysis will examine how the interviewer can be seen as 'complicit' (Gunaratnam, 2003) and as 'involved' by illustrating, from the content of interviews, how the 'giveness' of national identity cuts across the interview context and to illustrate how the interview interaction itself can be seen to be premised upon certain shared implicit understandings of the interviewer and interviewee as 'white British'. The analysis undertaken here then will proceed with a more thorough sense of the interviewer as involved, through adopting something analogous to the notion of 'constitutive reflexivity' (Woolgar 1988) in which ' the author constitutes and forms part of the "reality" she creates' (Woolgar 1988:22). By taking this step, it is possible to examine the exchanges between interviewer and interviewee in a purposive way. A common criticism of many uses of qualitative interview data, for example, is the scarce attention that is paid to the active role of the interviewer. In response to this, Rapley (2001:304-5) argues that 'an awareness and analysis of interviewers' talk in producing both the form and content of the interview should become a central concern for all researchers when analysing interview data' (emphasis in original). By presenting extracts from our respondents in isolation, we downplay the active role of the interviewer and the fact that interviewee's talk is contingent upon the interview as a specific form of interaction with its own particular enabling and constraining structures. In order to provide an immediate illustration of this approach, consider the brief extract below taken from one interview with a white male in his fifties.

National identity and Interviews as Interactions

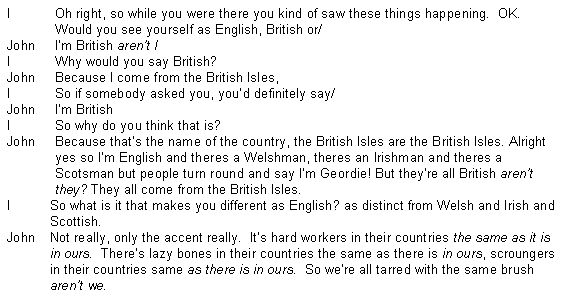

Extract 1[3]

|

4.1 A notable characteristic of this extract is that the exchanges are largely brief. There is little expansion by the respondent initially and the interviewer appears as equally involved. Prior to this particular passage, the respondent had expressed a number of fairly hostile views towards immigration and what he saw as 'people coming in getting everything'. The interviewer, uncomfortable with such statements, had tried to contest these views by asking the respondent to state his grounds for such claims. In providing this, the respondent had talked about how in his work he had 'seen' these people 'just hanging about and doing nothing'. Thus what we see at the outset is what could be seen as quite an ironic quip by the interviewer before deciding to quickly move on. This is important because it highlights that, going in to the talk about national identity, a clear distance had already emerged between respondent and interviewer on politics, racism and anti-racism.

4.2 In this particular interview, this shortness may be due to the lack of rapport between interviewer and respondent and the distance in relation to racism/anti-racism that had already preceded this passage. Yet despite this line of distance, there is also a strand of sameness between interviewer and respondent in the above extract. We see here the responding claiming a 'British' identity but in a way which portrays this claim as self-evident or obvious. It is self-evident to the respondent that he is British and this is highlighted particularly by the use of 'aren't I', 'aren't they', 'ours' and 'aren't we'. This is important because it has two aspects: firstly that it is self-evident or matter of fact to the respondent that he is British and secondly, that it is self-evident to the respondent that the interviewer should also see him is British and, indeed, that their Britishness is shared. This highlights how assumptions of shared common knowledge between interviewer and respondent form part of the interaction. There is accepted knowledge about who the British are in this case the English, Scottish, Irish and Welsh, and also the regional differences within England. Such an account by the respondent however are always co-productions in that the exchanges are framed by what the interviewer and interviewee are seen to share a national identity.

4.3 Of course, one can only speculate as to how others see one's social identity, and in the absence of any explicit grounded reference by the respondents as to my national identity, I feel largely unable to provide much consideration on this matter here. To this I can only add that my own national background, being born and brought up in Wales, and as a Welsh speaker, was never prompted by the respondents. In fact, having examined all 100 interviews, the only occasions when my 'Welshness' did manifest was through my own self-disclosure, and this was always in accommodation to a respondent reporting a 'Welsh' connection. Research on ethnic, linguistic and national identity construction has identified a range of socially available markers by which such identities may be assigned to others. These include accent, body language, clothing, manners, name, physical appearance or other aspects of personal background which when brought to bear, may provide a cue for ethnic, linguistic and national categorization. In that the interviews took place in England, with a white interviewer from a university in England, then, in the absence of any cues to the contrary (I am often told that I 'don't sound Welsh' and have an accent that could easily be mistaken as 'southern English'), a tacit white Britishness between researcher and respondent prevailed. A further complexity is that 'Welsh' need not sit in opposition to 'British', but as a dimension of it. As such my identification as 'Welsh' does not necessarily preclude my identification as one of 'us'. Did I, in attempting to maintain an identity-neutral position, also implicitly reproduce the normative identity of the context of the research? The next extract is also intended to highlight the involvement of the interviewer, but in order to illustrate a different point.

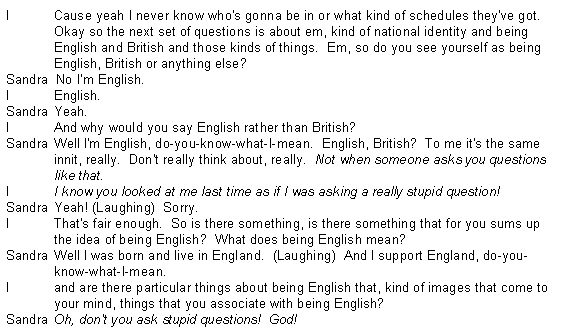

Extract 2

|

4.4 There are a number of significant points that can be made about this extract. To begin with for instance, we see the 'English, British all the same' construct that is commonly made by English/British identifiers. We also see, and this is a point I will discuss in greater detail below, the way the respondent qualifies her identity choice by drawing on certain criteria of national identity ('Well I was born and I live in England'). Again, however, as with Extract 1, Extract 2 is characterised not simply by what the respondent says but largely by the exchanges between respondent and interviewer. As in all the interviews, we aim to get our respondents not simply to provide an identity choice, but to subsequently reflect and talk about this choice. On two occasions in this extract, we see the interviewee experiencing some difficulty in doing this, and to deflect this difficulty by drawing attention to the question itself ('Not when someone asks you questions like that'). The interviewer then responds by saying ('I know you looked at me last time as if I was asking you a really stupid question). By focusing on this exchange, we can see national identity agreed upon by both participants as something that is difficult or unusual for people to talk about. In doing so this highlights the relevance of the notion of 'complicity' (Gunaratnam, 2003) to the interview interaction. Both interviewer and interviewee are complicit in their orientation to the interview topic as 'difficult', 'unusual' or even 'absurd' (Antaki, 2004).

4.5 It is noticeable that these two extracts, like many others, have a particularly 'short' quality to them in which the tone of the discussion works at a very flat level. They have the feel that the discussion hasn't really managed to get going. Indeed, in many of the interviews, it appeared that the direct discussion of 'their' national identity had a particularly flat, formulaic and ordinary quality while more open-ended discussions about the country, about how Britain is changing and about how it might be seen as a multicultural society were more discursive, animated and even resentful (Fenton & Mann, 2006).

4.6 At the outset of this article, attention was drawn to the ways in which people draw on and use national categories as ways of articulating or making sense of lived experience. However, to what extent can the use of national categories (English/British) by the interviewer in formulating questions be seen to reproduce and reinforce a respondent's use of national categories? This question identifies the central problematic that this article seeks to address. It suggests that the questions asked by the researcher makes a decisive intervention in the kinds of knowledge that is produced within the interview account. In particular it suggests that the interviewers questions provides the framework for the respondents' talk. It is perhaps not surprising that respondents should reproduce the 'having' of a national identity in a self-evident, unproblematic fashion, if they are prompted to do so. At the same time, such framing by the question also provides an enclosure to work against and thus an opportunity for the respondents to contest what they see as the assumptions inherent in the question asked.

4.7 Within the interviews, the topic of national identity was instigated by the interviewer through asking a standard question: "Do you see yourself as English, British, or what"? This is a standard question which can also be found in survey research on national identity. This question was asked in all of the interviews. Although in practice, as we shall see, the actual construction of the question did vary slightly. A number of further observations can be made about this question. Firstly, it fixes 'English' and 'British' as the normative national identities of people in England. In turn other possibilities require stating by the respondent. Secondly, the ' or what' part of the question is also critical in that it offers the possibility of other national (or social) identities to be had. As such, this question is different to a question which asks 'do you see yourself as English or British?' a question which is interested in whether people see themselves primarily as English or British although the question was occasionally interpreted to mean this. Finally, this is not a question which is spontaneously conjured up by the interviewer, but forms part of a topic guide that has been formulated and deliberated over at some length in advance. Moreover, it is a question which the respondent may never have thought about before, thus creating a disparity in knowledge of the topic, and a desire for the interviewer to avoid wanting to appear to know more. Further still, the respondent may recognise the question as designed for the purposes of eliciting particularly heightened (nationalist) discourses, rather than as a question of some otherwise general public or societal importance. Extracts 3 and 4 below illustrate the different ways in which the deployment of 'English' and 'British' categories by the interviewer is also subsequently reproduced by respondents.

Reproducing and Resisting National Categories

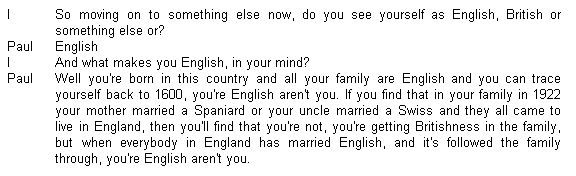

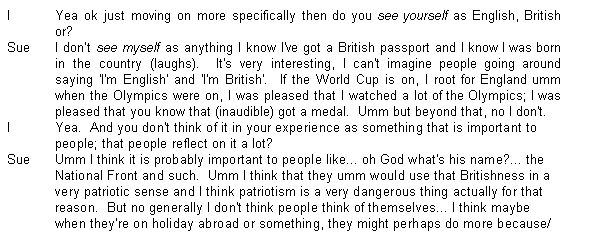

Extract 3

|

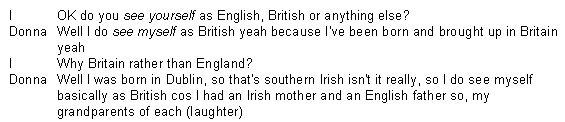

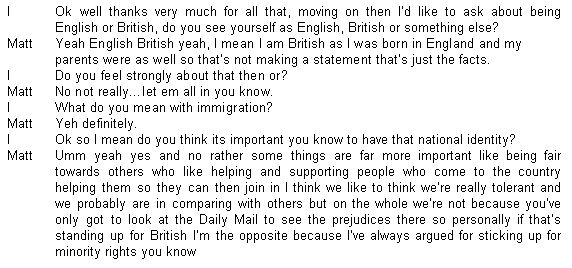

Extract 4

|

5.1 In the above extracts, it is striking just how these respondents consider their identity choices as following a generally accepted, unproblematised formula in order to qualify their national identity choice. They also identify how respondents attend to further probings about national identity and in particular how they 'know' their national identity. Or the ways in which people might qualify their responses. The first thing I wish to demonstrate about these responses is that they are constructed in a formulaic way. That is as pertaining to a prescribed set of widely agreed criteria that are commonly related to nationality and the particular criteria used in these cases are where you are born, where you're parents are born and also where you've lived. As such ones identity choice is qualified as a result of deductive reasoning on the part of the respondent (for example, 'I do see myself as English/British because '). As McCrone (1998:629) states, such criteria birth, residency, ancestry and also upbringing can be seen as the 'raw materials of national identity' which people draw on when making their 'identity claims'. And as in the second case above, even those who don't have all the 'right' criteria can still accept them as the basis for inclusion and exclusion. Within this extract however the respondent's talk is explicitly linked to the way in which the question was initially offered. In particular, the question of 'Do you see yourself ' is replied to in terms of 'I do see myself ' My use of the term formulaic here is also similar to what Edwards (1997) refers to in discourse analysis as 'script': 'a way of invoking the routine character of described events in order to imply they are features of some (approved or disapproved) general pattern' (see Silverman, 2001:184). As such, these formulaic responses can be interpreted as presenting the questions of ones national identity as a simple narrative, or a routine script in terms of their ordinariness rather than their extraordinariness, politicisation or controversy.

5.2 People not only talk with or through national categories but talk against them. In these cases below, this is done by making explicit the underlying assumptions that are seen as informing the question. By doing so, they avoid the inference that the ideological significance of their views can be determined from their banal categorical membership that is, that their membership is significant to them.

Extract 5

|

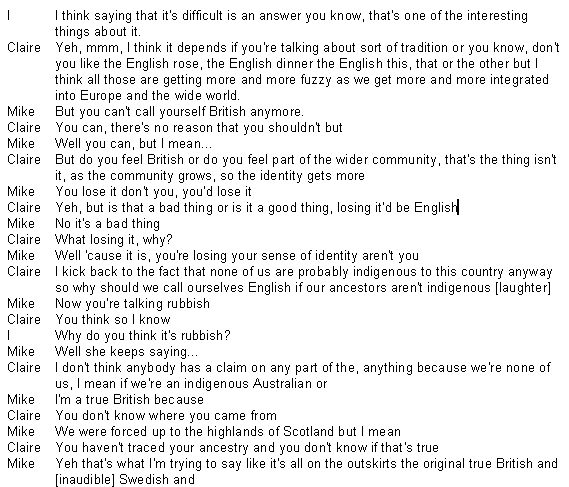

Extract 6

|

5.3 Again, in extract 5, we can see Sue's response as a direct reformulation of the interviewer's question ('Do you see yourself ' 'I don't see myself as anything'). Sue rejects the idea that her national belonging forms an important part of how she herself sees the world. Nor, indeed, can she imagine it having any importance for anyone else. At the same, she cannot dismiss this completely due to a perceived facticity around having a passport, which says 'British' and being born in 'Britain'. That said, for Sue, this facticity of the individual-national connection should not proceed to any patriotic sentiment, which would be dangerous. As Condor and Abell state (2005:2), respondents may manage concerns over rationality by 'framing' their claims by distinguishing 'national self-identification as a matter of objective self-knowledge ('being') from matters relating to sentimental national attachment ('feeling')'. For Matt (extract 6), his 'English' and 'British' identification is an expression of 'fact', the reality of things, rather than 'statement', or preference. He is English/British because that is where he and his parents were born but he is also careful to ensure that this 'fact' should not imply any attachment. Rather, his ideological sentiments lie more with a sense fairness and equality towards others, which is more important than national identity.

5.4 Both these extracts highlight the different ways in which people might actively minimise the ideological significance of their response. In doing so we see the idea of having a national identity or national belonging as unimportant or insignificant and there are particular uses of language by which this is accomplished. In the interviews, it is simple terms such as: 'just'; 'happen'; and 'that's all' that can be seen to do this. Given that the respondents have been invited by the interviewer to choose themselves as English or British or anything else - that is 'as national' then what these responses do is counter the potential insinuation that there is some greater ideological attachment to these national categories. As such 'English' and 'British' are represented as point-zero identities - as 'just places where people live and that's all' rather than things that they identify with and have emotional attachment to.

5.5 Therefore, it is not simply that people are talking about national identity. Rather, in doing so, they are implying or saying something about its significance to their sense of self. A useful idea here is that of 'outsiders' resources' - because they are 'constructed in the absence of members' accounts, they are assumptions to be resisted' (Widdecombe 1995:122). Thus people achieve resistance not to their subordination but to 'what is generally known or assumed about their lives' (1995:123). By failing to attend to how people themselves see the significance of their own identities we ignore how the assumption of significance itself becomes a point of resistance.

The Possibility of Challenge?

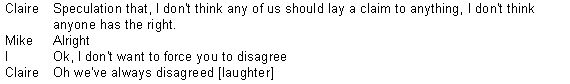

6.1 The extracts thus far have been drawn form one-on-one interviews. In extract 7 however the example is taken from a joint interview involving a female and male couple, Claire and Mike. As with many of the extracts, there is considerable diversity in the kinds of themes that are present here. What we gain from this joint interview however is an appreciation of the interaction and contestation of discourses between the respondents themselves. Indeed we can be note the relatively minor role that the interviewer plays within these sequences in comparison to others. In particular, I wish to draw attention to the way in which the first respondent, Claire, take on the role of questioning and probing the views of the second respondent, Mike.Extract 7

|

6.2 What is significant here is how the two respondents, as people who know each other, are able to exchange views in a far more challenging manner (for example, 'now you're talking rubbish' and 'you don't know where you came from'. We can also read these respondents as representing two contrasting discourses on the changing scene of 'England/Britain' and its relationships to cosmopolitanism, globalism and Europe. For Mike, this changing scene is viewed negatively as a loss of identity and a death of 'Britishness'. For Claire however, we see not only an embracement of these changes but the rejection of any rightful claim to belonging and the ownership and place. As these discourses are played out by the respondents, we witness a number of exchanges in which both the interviewer and Claire are complicit in contesting Mike's claims to 'know'. We have the sense here therefore that, in this extract, Claire was able to maintain her 'embracing' discourse as the dominant discourse within the encounter through her alignment with an interviewer, who shared her world view, in opposition to the world view of Mike.

Conclusion

7.1 Compared to the sociology of ethnicity and racism and work on ethnic and racial categorisation, national identity remains an empirically under-investigated area in both qualitative interview research and discourse analytical studies as well as in sociology more generally. In this article I have provided a reflexive consideration of the ways in which national identity is articulated by ethnic majority individuals in England. The paper began by commenting on the methodological problem which is implicit within Michael Billig's notion of banal nationalism, and indeed, in many similar studies around the notion of everyday nationalism/national identity, drawing in particular on those influenced by social constructionism. Attention was then drawn to discourse studies and the transactional nature of interviewing and to the importance of considering the role of the interviewer as involved in co-producing the interview account. A brief outline of our research on the ethnic majority in Britain was then provided.7.2 The analysis undertaken here has focused primarily on the interpretation of a series of extracts taken from a much larger corpus of interviews. These instances have been selected in order to illustrate the importance of considering the interactive nature of interviews. Through adopting this approach I have demonstrated how both the problematizing and unproblematizing of national identity is, at least in part, contingent upon the relationships established and the reflexive exchanges between interviewer and respondent (as well as between respondents themselves). This was done however, not with the aim of discrediting the findings of qualitative interview studies, but in order to offer some useful insights into future research in this and in related areas. In particular, I have drawn attention to three key dimensions of this: firstly, how the formulation of questions themselves organise an individual's response; secondly, how the interviewer's (non-) interventions on certain occasions raises issues of complicity and contestation; and finally, to how the researcher's (national) identity is seen by the respondent to be shared in a taken for granted fashion.

7.3 However, there are good reasons for believing that the conversational conjectures around national identity identified here are also evident within everyday practices more generally. For example, there is a noteworthy correspondence between these findings and Habermas' (1987) theory of communicative action. In his elaboration of the lifeworld, Habermas (1987:204) argues that all communication involves a range of 'unspoken presuppositions' that must be 'mutually understood' in order for a topic of discussion to be raised, and subsequently problematized. As Habermas states:

the lifeworld to which participants in communication belong is always present, but only in such a way that it forms the background for an actual scene. As soon as a context of relevance of this sort is brought into a situation, becomes part of a situation, it loses its triviality and unquestioned solidity'. When it becomes part of the situation, this state of affairs can be known and problematized as a fact, as the content of a norm or of a feeling, desire, and so forth. Before it becomes relevant to the situation, the same circumstance is given only in the mode of something taken for granted in the lifeworld, something which those involved are intuitively familiar without anticipating the possibility of its becoming problematic (Habermas 1987:123-4, italics added).

7.4 By viewing national identity as a specific form of taken for grantedness, one can question whether the shared assumptions around 'our' national identity could at all be avoided. This does not necessarily mean that national identity is always there within everyday life, in the way that the lifeworld is deemed to be, but that it represents a specific knowledge stock that is mobilised only when it becomes relevant to a situation. As this analysis has shown, while most people most of the time do take their national identity for granted, its facticity can still be challenged through dialogue. Furthermore, even if people do talk as if their national identity is self-evident both to themselves and to their immediate others, this does not preclude an indifference towards how much 'being English or British' actually matters to them as individuals (see Fenton 2007 forthcoming for an exposition of this).

7.5 By paying closer attention to the context of the interview, we can see how asking questions about national identity provides opportunities not only to reaffirm this national identity as derived and self-evident, but also for individuals to creatively resist such framing. As such the interview, as a form of communication, provides a frame which is both constraining in that one cannot step outside its parameters - and enabling in rendering such taken-for-granteds open to contestation.

7.6 If this interpretation is correct, these findings may also have implications for policy makers with an interest in changing white majority attitudes. For instance, within anti-anti-racist discourses, defences of 'majority culture' are commonly presented as defences of the everyday common sense of ordinary people. Concomitantly, antiracism and multiculturalism represent public sensibilities of a liberal intellectual elite that is 'out of touch' (Kundnani 2000). This could be because of the tendency for antiracism to be consumed through the distorting mediums of politics and the media rather than as part of ones local experience. If so, then policy makers need to consider ways in which this disjuncture between antiracism and everyday common sense can be tackled through supporting the conduct of anti-racist and multicultural work at the local level.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Steve Fenton, Yasmin Gunaratnam and the anonymous referees for their constructive comments on earlier versions of this article.

Notes

1Arguably, this is because ethnographic and qualitative interview studies of national identity have formed only minor part of overall nationalism scholarship which falls as much within the historical and political sciences as it does within the disciplines of anthropology and sociology (Thompson & Fevre 2001).2Fenton, Steve & Robin Mann: 'Nation, Class and Ressentiment'. This project forms part of the Leverhulme Programme on Migration & Citizenship, held jointly by University of Bristol and University College London.

3In each of the extracts, I have italicised particular words or statements in order to highlight their relevance to the key themes of this paper. All respondents' names are pseudonyms.

References

ANTAKI, C. (2004) 'The uses of absurdity' in H. Van den Berg et al (eds.) Analysing Race Talk: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ATKINSON, J. M. & Heritage, J. (1984) Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BECHHOFER, F. et al (2000) 'Constructing national identity: Arts and landed elites in Scotland, Sociology, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 515-534.

BILLIG, M. (1988) 'Prejudice and tolerance' in M. Billig et al (eds.) Ideological Dilemmas. London: Sage.

BILLIG, M. (1995) Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

BRUBAKER, R. (2004) Ethnicity without Groups. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BERGER, P. & LUCKMANN, T. (1967) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. London: Allen Lane.

CONDOR, S. (2000) 'Pride and Prejudice: identity management in English peoples talk about "this country"', Discourse and Society, Vol. 11, No.2, pp. 175-205.

CONDOR, S. & ABELL, J. (2005) 'Framing and displaying English national identity', Lancaster University: Institute of Governance,

DE CILLA, R. et al (1999) 'The discursive construction of national identity', Discourse & Society, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 149-173.

EDWARDS, D. (1997) Discourse and Cognition. London: Sage.

FENTON, S. (2007, FORTHCOMING) 'Indifference to national identity: what young people think about being English and British', Nations & Nationalism.

FENTON, S. & MANN, R. (2006) 'The state of Britain: The ethnic majority and discourses of resentment', Leverhulme Conference on Mobility, Ethnicity and Society, University of Bristol. March 18th 2006.

FOX, J. (2004) 'Missing the mark: national politics and student apathy', Eastern European Politics and Societies, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 363-393.

GUNARATNAM, Y. (2003) Researching 'Race' and Ethnicity: Methods, Knowledge and Power. London: Sage.

HABERMAS, J. (1987) The Theory of Communicative Action, Volume Two: Lifeworld and System. Cambridge: Polity Press.

HESTER, S. & HOUSLEY, W. (2002) 'Introduction: Ethnomethodology and national identity', in S. Hester & W. Housley (eds) Language, interaction and national identity: studies in the social organisation of national identity in talk-in-interaction. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

JACOBSEN, J. (1997) 'Perceptions of Britishness', Nations & Nationalism, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 181-199.

KIELY, R. et al (2001) 'The markers and rules of Scottish national identity', The Sociological Review, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 33-55.

KOOLE, T. (2003) 'Affiliation and detachment in interviewer answer receipts', in Van den Berg et al (eds.) Analyzing Race Talk: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

KUNDNANI, A. (2000) '"Stumbling on": Race, class and England', Race & Class, 41(4): 1-18.

MCCRONE, D. et al (1998) 'Who are we? Problematizing national identity', The Sociological Review, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 629-652.

MCCRONE, D. (2002) 'Who do you say you are?', Ethnicities, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 301-320.

RAPLEY, T. J. (2001) 'The art(fullness) of open ended interviewing as interactions', Qualitative Research, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 303-323.

SILVERMAN, D. (2001) Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction. London: Sage.

TAJFEL, H. (1978) (ed.) Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. London: Academic Press.

THOMPSON, A. (2001) 'Nations, national identities and human agency: putting people back into nations', The Sociological Review, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 18-32.

THOMPSON, A. & DAY, G. (1999) 'Situating Welshness: "local" experience and national identity' in Fevre, R. & Thompson, A. (eds) Nation, Identity and Social Theory: Perspectives from Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

THOMPSON, A. & FEVRE, R. (2001) 'The national question: sociological reflections on nation and nationalism', Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 297-315.

TYLER, K. (2004) 'Reflexivity, tradition and racism in a former mining town', in Ethnic & Racial Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 290-309.

VAN DEN BERG, H. et al (2003) (eds.) Analyzing Race Talk: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Research Interview. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

VAN DIJK, T. A. (1987) Communicating Racism: Ethnic Prejudice in Thought and Talk. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

VERKUYTEN, M. (1998) 'Personhood and accounting for racism in conversation', Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 147-167.

WETHERELL, M. & POTTER, J. (1992) Mapping the Language of Racism: Discourse and the Legitimation of Exploitation. Hemel Hempstead, Herts: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

WIDDECOMBE, S. (1995) 'Identity, politics and talk: the case of the mundane and the everyday' in S. Wilkinson & C. Kitzinger (eds.) Feminism and Discourse: Psychological Perspectives. London: Sage Publications

WOOLGAR, S. (1988) 'Reflexivity as the ethnography of the text' in S. Woolgar & M. Ashmore (eds) Knowledge and Reflexivity: New Directions in the Sociology of Knowledge. London: Sage Publications.