Love Lives at a Distance: Distance Relationships over the Lifecourse

by Mary Holmes

Flinders University

Sociological Research Online, Volume 11, Issue 3,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/3/holmes.html>.

Received: 2 Dec 2005 Accepted: 23 Aug 2006 Published: 30 Sep 2006

Abstract

Distance relationships may be increasingly undertaken by dual-career couples at some point in their life course. Although this can make it difficult to quantitatively measure the extent of distance relating, qualitative analysis of distance relationships promises to give considerable insight into the changing nature of intimate lives across the life course. This paper indicates the kind of insights offered via analysis of exploratory research into distance relating in Britain. What begins to emerge is a picture of distance relating as offering certain possibilities in relation to the gendered organisation of emotional labour and of care in conjunction with the pursuit, especially of professional, careers. These possibilities might be more realistic, however, at certain points in the life course. Nevertheless, this new form of periods of separation between partners, tell us a considerable amount about how people approach the challenges of maintaining a satisfying and egalitarian intimate life, involving caring relationships with others, within contemporary social conditions.

Keywords: Distance Relationships, Commuter Marriage, Intimacy, Lifecourse, LAT

Introduction

1.1 For couples to share a residence throughout the life course may become less common as labour markets become less localized and more globalized, and as women's workforce participation increases. This separation between couples is likely to take rather different forms than in the past, when it usually involved the husband going away to work or fight (Gerstel and Gross, 1984: 158-182, Hollowell 1968, Tunstall, 1962). Such families are still found but these are heterosexual relationships which appear to conform to conventional gender roles. The women remain within the family home, responsible for caring for any children, and the men while away usually stay in institutionally provided or temporary accommodation (Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, 2002; Chandler, 1991; McKee and Mauthner, 2000). As women have entered the workforce, and in particular the professions, the pattern does appear to have changed. What my work on distance relationships can help establish is the social significance of new types of distance relationships involving non-resident dual-career couples. Such relationships potentially challenge many ideas about gender relations, intimate relations and their place within the life course.1.2 I define distance relationships as ones in which couples spend at least two nights a week apart, or are separated for longer periods on a regular basis. When separated they each have a relatively permanent and non-institutional residence. These relationships, I argue, are significantly different from the historically familiar couples mentioned as well as from single-residence dual-career couples.

1.3 Although dual-career relationships have been of interest to sociologists for some time (e.g. Rapoport and Rapoport (1976), there has been very little work on distant relating. Geographers have given some attention to distance relationships (Green et al 1999), but examine them as one form of work-related mobility rather than in relation to intimacy. Within sociology there has been interest in new living patterns similar to those I am investigating, for example, Sue Heath (1999, 2004) has looked at transhousehold relationships amongst young people, but these may be less enduring relationships than the kind in which I am principally interested. There is also Irene Levin's (e.g. 2004) work on couples who Live Apart Together (LATs), of whom those relating at a distance are a subset, but one for whom distance poses particular challenges. There appears to be only one significant sociological study so far done on this phenomenon.[1] In 1984 Naomi Gerstel and Harriet Gross published their findings from a study of 121 individuals experiencing what they called Commuter Marriage. I engage in more detailed discussion of their work, elsewhere (Holmes 2004a).

1.4 Here I draw on Gerstel and Grosz's study, in conjunction with my own exploratory research, to help express some preliminary thoughts about distance relating over the lifecourse. I argue that dual-residence distance relating amongst dual-career couples is a new pattern. Couples are often apart, reuniting either each weekend or being apart and together for longer periods. I suspect that this pattern is largely confined to professionals (though hope to pursue this in a future study), because sufficient money and some flexibility are required in order to maintain two residences. This having of two 'homes' differs from the aforementioned old pattern of men going away to work and usually staying in institutionally provided accommodation and from the more recent situation in which women leave their families in developing countries to seek (live-in) domestic work in wealthy nations (Ehrenreich and Hochschild 2003). One useful way of approaching some of these differences is through the frame of the life course. This allows us to examine distance relationships in ways that will shed light on broad social changes in intimate life. A qualitative understanding of distance relationships is also here used to critically interrogate the life course. The paper is organised around a questioning of whether and why distance relating might be something done when young, as part of getting started in a career, and prior to attaining family responsibilities. It will become clear that qualitative research on distance relationships can illuminate the difficulties of conducting intimate relationships across life courses in which caring for others and working for a living are often in conflict. But this discussion needs to be premised by a brief explication of the likely occurrence and significance of distance relationships within the life course of contemporary individuals and a brief explanation of my study and sample.

Distance relationships within the life course

2.1 The life courses of contemporary individuals are complex, and it may be that distance relating may increasingly form one component in that complexity. It is contended by many sociologists that de-industrialisation and the fragmentation of traditional institutional and identity structures have disrupted the formerly relatively neat shifts from one life stage (say childhood) to another (such as adulthood) (Featherstone and Hepworth 1991). It is important not to represent some past 'golden age' in which people made simple linear transitions from youthful singleness to work and family responsibilities (Goodwin and O'Connor 2005). Nevertheless, there is some evidence that the kinds of transitions through the life course that people make in relationship terms are less straightforward than previously. Young people might move out and back to the family home, perhaps live in peer-shared households or cohabit in between, and are increasingly likely to have children without, or before, marrying (see Heath 2004, Jamieson 1998). When people are partnered it is also now no longer certain that they will cohabit, perhaps living apart either nearby, or at a distance (Levin 2004).2.2 It is difficult to ascertain the extent of distance relating as a way of life, especially if it is only a brief episode within a couple's history. Distance relationships remain largely invisible within snapshot measures of relationship types, given that many large statistical surveys take the household as their unit of measurement. However, there has been some attempt to establish within Europe how many people may have relationships with someone in another household. Haskey (2005) has used the Omnibus survey, Ermisch (2000) has analysed data from the 1998 British Household Panel Survey and Kiernan (1999) from the European Family Fertility studies of the 1990s. Drawing on these analyses it seems that around one third of unmarried people in Europe under thirty-five are in fact in non-cohabiting relationships. However, it is not possible to tell how many of these are of a long-term nature. Haskey (2005) estimates that around two million people in Britain are seriously living apart together, but it cannot be said how many are at a distance, rather than within the same locale. In the United States Guldner (2003: 1) estimates that within the general population, as many as two and a half million people (not including the armed forces) might be in some form of long-distance relationship. Guldner (2003: 6) also claims from his research that one quarter of premaritals are in a long distance relationship and three-quarters have been at some time. Many of these relationships are youthful boyfriend/girlfriend ties that may not endure, often between college students yet to establish careers. Nevertheless these figures may indicate that many couples 'do distance' at some time. However, all these figures remain indicative only, and indeed collecting more accurate ones might be problematic given that many distance relationships are transitory. For many dual-career couples a period, or periods, of relating at a distance might be necessary if they wish to pursue their chosen careers (Green 1997: 646). People may make a series of non-permanent moves of varying duration, some of which may involve living at a distance from partners (Bell 2001). Whilst quantitative data on the extent of such relationships may be difficult to obtain, it is possible to get insight into the experience of distance relating as part of people's life course via qualititative study.

Study and sample

3.1 In this paper I raise some issues and questions based on the data gained from the first phase of my ESRC funded study of distance relationships[2], which investigated to what extent distance relationships challenge many common sense and sociological assumptions about intimacy in contemporary life. This study gathered data on British couples relating at a distance in which at least one partner is an academic. Overall I have questionnaire data on twenty-four couples. This data gives information on forty seven individuals, as one person's partner did not participate. From this sample, fourteen couples were interviewed, three as part of the pilot study in 2002. Nine couples, plus two of the women partners on their own, were interviewed in the first phase of the ESRC study in 2004. I here draw on five of those eleven main interviews. Analysis of the remaining interviews is still underway. My own relationship is included in the sample. I intend to fully discuss elsewhere the implications of using my own relationship, here I will simply say that my partner and I completed the questionnaire, and talked through the interview schedule together. This data was recorded, analysed and anonymised as with the other participants. Particular care has been taken to anonymise all the data, given the relative smallness of the academic community. For example, identifying people's workplaces and places of residence could potentially identify them, so I have adopted the convention of calling the place where the woman heterosexual partner works/lives: 'Hertown', and where the man works/lives: 'Histown'. In lesbian relationships I use 'Hertown' and 'Hercity' to distinguish the partners' places of work/residence. Although this is a small sample, it has provided rich qualitative data and is the beginning of further research in this area.3.2 Later I intend gathering information on other professionals and eventually will look at other forms of distance relating amongst less privileged groups. Beginning with dual-career professionals is based on an assumption that if individualisation processes are extending to women (Beck and Beck Gernsheim 1995) this will be most obvious amongst elites (see Holmes 2004a). What I have to say here is tentative and suggestive based on a fairly small number of early questionnaires and interviews. My sample is not representative; it was collected purposively by asking mediators (friends, colleagues, and acquaintances) across the UK from both old and post-1992 universities to help me contact anyone they knew who was in a distance relationship. The information on age, years in present job and living arrangements presented below is taken form the questionnaire data. This provides some sense of the respondents as a group, and comparisons are made with Gerstel and Gross's sample to try and establish whether they might be relatively typical of distance relaters. This data can however only give possible hints about how distance relationships might fit within the life course. The interview data is drawn on to consider more complex questions about how intimacy and care can be maintained at a distance. In evaluating the information I present here it is useful to know some of the basic information about all twenty-four couples.

3.3 The majority (eighteen) of the couples have been a couple for over five years. Eleven couples had spent over five years apart. The longest distance I encountered in the study was a couple maintaining a relationship when one was in South East Asia and the other in Britain. However, this couple are no longer together. Most of the respondents were living within Britain and not usually at completely opposite ends from their partner. The interviews confirmed my suspicion that it was not the actual distance that was crucial but the travelling time. Five hours seems an interesting cut-off point, for reasons to be explored in future. Only eight out of forty-seven individuals reported traveling for over five hours. Twenty-two of the forty-seven individuals made most of their journey by train, thirteen mostly by aeroplane, the rest by car or coach, with five reporting they did not travel (their partners came to them). Cost of travel varies considerably, but it seems that close to half of the respondents reported paying between twenty and fifty pounds each per return trip.

3.4 The three couples selected for the pilot interviews were chosen because they are both typical of the distance relaters in my sample and yet vary in terms of sexuality, marital and family status, the length of their relationship and the regions in which they reside. They are typical in travelling between two and five hours to reunite and seeing each other weekly or fortnightly. This appears to be a common pattern for distance relating (Gerstel and Gross, 1984). Natalie and Rebecca were a young lesbian couple, in their early twenties, travelling between different regions in the North of the UK whilst pursuing undergraduate studies at separate universities. At the time of the interview (since then Natalie has informed me that the relationship has ended) they had been together about a year, but relating at a distance for only a few months. They saw each other every second weekend, with Natalie normally travelling to see Rebecca. In comparison, Margaret and Joe had been living apart for three years, with a slight break courtesy of maternity leave. Margaret and Joe are both academics in their mid-thirties, working in regions a few hours train journey apart. They were chosen because they are married and had a young baby, which might be presumed to add to the complications of distant relating. In this they were different from Meg and Ben, who are also both academics and in their thirties, but are not married and do not have a child. Like Margaret and Joe, they have been together between ten and fifteen years, but Ben and Meg have spent most of that time relating at a distance. Both couples see each other every weekend. Of the three couples Meg and Ben have the longest journey to visit each other, but like all the couples this is facilitated by the relative flexibility of academic work. Rebecca and Natalie, though not paid academics were also organizing their relationship around university timetables and requirements.

3.5 Before leaving Britain I was able to conduct the first main phase of interviews with academics. Eleven interviews took place, most with couples, but two with the woman only. These couples were again chosen to try and cover various age ranges, times together (and apart), and distances between partners and sexualities. Two lesbian couples completed questionnaires, and one was interviewed but to include that data as well as that from Natalie and Rebecca's interview would be to misrepresent what is primarily a heterosexual sample. Here I use data from five of the main interviews. Donna and Wendy I interviewed alone because their respective partners Sam and Harry preferred not to be interviewed. Donna is in her forties, Sam slightly younger. They have been together almost fifteen years and she usually travels every weekend to see him. They have never lived together. Wendy's partner Harry is not an academic, but in the armed forces. They are in their twenties and usually see each other every weekend if he is not overseas. They both travel for two to three hours to meet at the house they own together. They have been together around six years and lived apart about half that time. Joanne and Mark are in their thirties, have been together around ten years and lived apart for the last eight. To reunite each weekend they take turns to make about a four hour train journey. Allan and Jane, meanwhile, are both academics who have been together over twenty years, with a couple of periods of separation, this time for about five years. Jane spends four days away at her workplace, about two hours distant, driving back to work one day a week at their home. She then spends the weekend with Allan and their teenager. Martin and Lucy are over fifty, have been together more than twenty years and have, unlike Allan and Jane, spent most of that time apart. They also have children, now grown up. Already my description of the sample may challenge some preconceptions about distance relationships as something entered into by young people, early in their careers and before they have children. Further discussion of the data will now deal with these issues and in addition it will be considered what this data might reveal about caring relationships across the life course.

Age: Are distance relationships for the young?

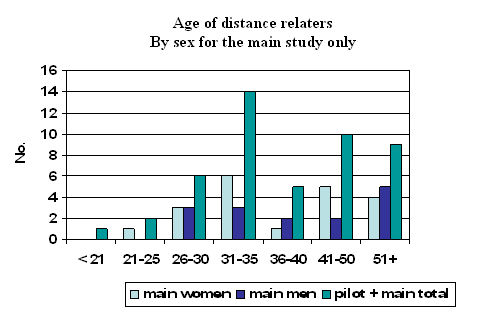

4.1 It seems plausible that distance relationships are something done when relatively young. In Britain, just over eighty percent of those with partners elsewhere are under forty, while closer to sixty-seven percent of cohabiters are under forty (Haskey 2005: 40-1). However, many twenty-somethings are likely to be living with parents and/or not ready to cohabit, rather than in committed LAT or distance relationships. Nevertheless, those with a partner living elsewhere are slightly more likely to be between twenty five and thirty-four than over thirty five (Haskey 2005: 40). Therefore although Gerstel and Gross's (1984) sample of 121 was non-representative their finding that sixty per cent of commuters were forty years of age and under seems reasonable. Thirty-eight percent were in their thirties. Around forty percent of my sample of distance relaters are in their thirties and about sixty per cent were forty and under. However, there are a not insignificant number of older couples. About fifteen percent of Gerstel and Gross's sample were over fifty, and a similar proportion of mine. This compares to population estimates of six or seven percent of those with partners living elsewhere in the over fifty bracket, whilst more like twelve percent of cohabiters are in that group (Haskey 2005: 40).

|

4.2 My sample is small and not representative and the relatively high number of older couples may arise from the fact that many of my most helpful mediators were close to that age range themselves. Nevertheless this is something worthy of further research. The LAT research indicates (e.g. Borell and Ghazanfareeon Karlsson 2003; Levin 2004), that older couples have reasons such as caring for children or parents which lead them to choose not to cohabit. Yet it is not clear whether they are more likely to live apart at a distance, than nearby. It is also uncertain how much choice is involved in distance relating, and many seem to view it as an unpleasant necessity in pursuing dual-careers (Holmes 2004b). Most of those I have spoken to express hopes that they will not be apart for long, whilst for many it seems to be longer than anticipated. Looking at older couples does indicate that distance relating can be a far from short-term arrangement. In my data, of the couples with one partner in the over fifty age group, four had been relating at a distance for six to ten years, and two couples for eleven to fifteen years; one of the former and one of the latter couples never having lived together. However, most of those in distance relationships are younger, perhaps because their job options are more constrained while establishing their careers, or because they are more able to do distance before having children. I will now explore these possibilities.

Are distance relationships an early career stage strategy?

5.1 Gerstel and Gross (1984) propose that commuter marriages are more likely in initial or trial career stages when professionals are building their reputation, but also much later in the stability-opportunity phase. I did not specifically ask how established people were in their careers, but most of the academics, of whom there were thirty-one, did indicate whether they were Lecturers or Professors when reporting their occupation. There were three students (one a postgraduate) in the pilot study and one researcher/student in the main study. Eleven of the main sample and four of the pilot identified themselves as Lecturers. A total of two labelled themselves researchers (both in the main study) – one of which was the researcher/student. One identified as a senior lecturer, and one as a reader. Professors totalled eight, one of whom added the designation 'retired'.5.2 The largest single group of those I surveyed were Lecturers, but there are also a reasonable number of Professors. The lack, within my sample, of distance relaters in middle career does fit with Gross's (1980) findings. 'Lecturer' can however, designate academics with highly varying numbers of years of experience. It may also be that some of those who have identified as Lecturers have used it as a generic description of what they do, not as an indication of their level, so they may be senior lecturers or readers, or even Professors. However, my data may provide some further support for Gross's (1980) suggestion that most couples who commute are either young childless people 'adjusting' to their new careers and relationships, or 'established' in their career and as a couple. The latter are likely to have grown up children and perhaps have shifted apart to gain promotion.

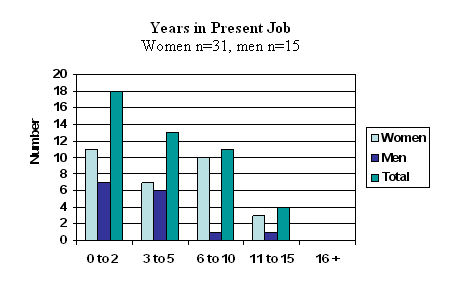

5.3 What we can see is that research so far indicates that those in distance relationships are mobile workers. Again my sample confirms Gerstel and Gross's (1984) research. My data shows that three-quarters of the respondents have been in their job less than six years, and a half two years or under. Data is missing for one man on this question.

|

5.4 A short time in the present job does not mean the respondents are novices in their career; they may have shifted jobs within academia. Indeed fourteen of twenty-four couples so far report having 'done' distance in previous jobs. Moves may be expected to involve compromise. So far the data is insufficient to indicate whether there is a gender dimension to these compromises, but that is something I will pursue in future. At present what seems clear is that distance relationships are likely to be connected to fairly high levels of job mobility, but that being a mobile worker is more likely for those yet to have children, or who have older or grown children.

Distance and the family life course

6.1 Most distance relaters so far studied are childless, or have grown children but some do have dependent children. Gerstel and Gross (1984) found it was rare for those with infants to commute, however they were able to construct a sample in which half their couples had live-in children. Four couples in my sample had children under eighteen currently living with them, while at least one other couple had previously managed childrearing whilst apart. One of the pilot couples had an infant when I interviewed them, although they thought their situation far from ideal. I asked this couple if their living arrangements might change "as you get further on with your jobs"?JOE: … I don't think we're really thinking about, you know, what will happen if we're still doing this in five or ten years time; I think we're thinking in the next year or two – because we have a kid – that we've kind of gotta put the lid on it [laughs a little]

MARY: Right

JOE: and get back to the same place somehow, even if, you know, oh one of us packs it in, or whatever.

6.2 However, people are living apart precisely because of difficulties in both finding work in the same location and because they do not want to 'pack in' their jobs. Admittedly priorities may be reassessed when children arrive, but distance may still be felt to be the only solution. Some people in distance relationships do bring up their children while mostly apart. Jane and Allan had found that they had to be apart a few times in their almost thirty years together as a couple. Some of their shifts were prompted by the children's needs, but job situations allowing them to be together did not always work out and employment at a distance was again taken up. On one previous occasion Allan had one of their teenage children with him while Jane had the other younger ones with her. Later when they were back together Jane commuted almost two hours each way daily until the young ones got a little older and then she had started spending time away at Hertown during the week. Martin and Lucy had also brought up their children whilst relating at a distance, and the children had mostly lived with Martin. Both Lucy and Jane spoke of the 'maternal guilt' separation from their children caused, but there may also be advantages to distance relating for women.

Caring over the life course

7.1 Distance may give women some respite from emotional work at times in the life course when they might otherwise feel obliged to do this form of care. As Joanne says in answer to my question about what she thinks are the good things about distance relationships:JOANNE: [not having to] present a presentable face to the person I'm living with, I can just come home and if I'm grumpy nobody knows…In another interview Donna responds in a very similar fashion to the same question:

DONNA: one of the things that I like which is both the independence and the fact of being able to be grumpy or being able to just do what you want, without having to be civilised around someone else I don't actually have to make an effort to be civilised with somebody else and it's a big satisfaction

7.2 This makes it evident that emotion work is something done in relation to others and involves consideration of their emotions. While distance can reduce emotion work, this does not mean that those in distance relationships are free of obligations to care or of actual caring duties. To begin with, it is not necessarily the case that partners live by themselves when not together.

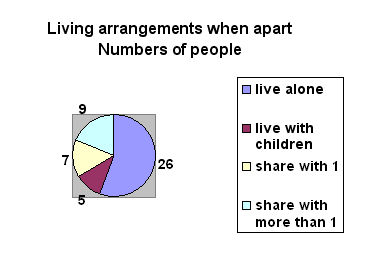

7.3 In the majority of my cases (twenty-six) people live alone when not with their partner, but many share their residence with others.

|

7.4 Indeed distance relationships and the sometimes complex living arrangements involved are one indication that media hype about the trend towards living alone may be exaggerated. Even if people do live alone, they may not do so all of the time, nor necessarily be without a partner, or lonely. They may be involved in caring for others they are living with when away from their partner. For example, Donna and Sam both live with their ageing parents and provide them support. This is noted as common in the LAT research (e.g. Borrell and Ghazanfareeon Karlsson 2003, Levin 2004). Alternatively, those in distance relationships may have to try to fulfill caring obligations to other kin who are often also at a distance given that distance relaters are likely to be highly geographically mobile (Green et al 1999). One instance is given by Cora Baldock, who (2000) has examined migrants' transnational family arrangements relating to the care of elderly parents. And although often apart from partner, and in some cases children, distance relaters will still be caring for them in some form. Caring at a distance presents particular problems, partly according to where individuals and their loved ones are within the life course.

7.5 The medicalised rationalisation of physical care typical in advanced capitalist societies (Foucault 1973, Illich 1975) does not accommodate well some of the embodied realities certain or likely to coincide with particular points in the life course, particularly where distance is involved. For those with infants, combining distance and childrearing illustrated how difficult physical care can be to rationalise. Joe and Margaret talk about this.

JOE: … So I've only had this like one night a week when I've been alone with [our ten month old Baby] and um, that was quite hair-raising sometimes at first, ah because he wasn't, he was breast fed, he wouldn't drink formula. Umm, wouldn't eat solids [M laughs a little]. So, the fact that the breast was on the move [all laugh]

MARY: Yeah right

JOE: was a real problem. Margaret had to do a lot of nightmare expresses.

MARGARET: It was a total, total disaster I think

7.6 Bodies do not always accommodate themselves to rational planning. Martin and Lucy, who also raised children while apart, were very aware that their arrangements relied very much on everyone maintaining good health.

LUCY: We have been very lucky, there was and I do remember, actually when erm we had committed to moving to Histown and I knew we were going to be commuting by plane, I do remember thinking this is fragile and it could so easily be umm ruined by ill health.If someone does fall ill their partner may not be able to be there to provide practical care. I asked Meg and Ben, childless and relatively young, about their caring arrangements.

MARY: What about when you're sick?BEN: Well when we're sick we look after each another if we're there and if we're not we sort of call up on the telephone and make soo soothing noises. That's about all we can do.

7.7 For young, usually healthy couples, there is likely to be less need to provide physical caring for any lengthy period, but if longer illnesses emerge the difficulty of caring from afar becomes apparent as Joanne and Mark found out.

JOANNE: And what about when I was ill? (pause) Did you worry about me when I was ill? …MARK: I would have been worrying but it was sort of a chronic thing that y'know you weren't going to be very different during the week than to what you were at weekends.

JOANNE: But it did mean you had to look after me. That you had to come down and visit me almost all the time for a least six months and you had to do my grocery shopping for me and we, we couldn't do stuff together, I was too sick to go to the cinema.

MARK: I think in some ways during that period it was actually good for me that we were apart 'cos it meant that while I was away I didn't have to worry about it. It took quite a lot of emotional stamina to look after you all the time

JOANNE: And I was living with, I was in a shared house when I was ill and so I had

MARY: Oh so you knew there were other people there right

JOANNE: Claire in particular would go and get medication , I mean she'd go to the supermarket and ask me if I needed a lift and she just kept an eye on me so, so if I was on my own you probably would have worried

MARK: Oh very likely yeah

7.8 Joanne notes the difficulties Mark endured to provide care for her, but he admits that distance also gave him a break from caring duties. If one partner is ill it can require considerable physical stamina if the frequency of travel has to be increased, and also considerable 'emotional stamina' to be providing live-in care. Mark mentions the advantages of being able to have a break, but this is possible as long as others can take over. Whether the opportunity to share care with others is more likely to be available to, or taken up by, men is a discussion I will postpone for other proposed papers. Here the point is that some relief from continued physical caring might be helpful and it is perhaps easier to involve others in care when partners reside elsewhere. Yet this might alter as couples age and care requirements potentially increase.

7.9 Although, Martin and Lucy in the excerpt above may be speaking of the children's as much as their own health, older couples in distance relationships may be more concerned about what happens if their own health begins to fail. Health problems related to ageing may make it difficult for individuals to cope with continued travel. Older distance relaters are seemingly those who enjoy good health, but small things such as the tiredness from travelling can begin to impact more. All my participants commented on the tiring aspect of the travel, but Jane for one thought that the tiredness was more acute as she got older. More serious breakdowns in health would be likely to necessitate some change in the distance between couples.

7.10 Yet it is not necessarily unwell bodies themselves that are the problem but the way in which physical care has been medicalised and rationalised in ways that do not account for the geographical distances between some couples and/or families. Access to care services is usually organized according to place of residence. It might be imagined that couples could face arguments about their entitlement to healthcare if trying to access health services when staying with their partner. My own experience was that an occasional visit to the doctor in my partner's town was not problematic, but it might be in some regions. And difficulties might arise if someone needed extensive hospital treatment whilst visiting their partner. None of my participants mentioned such healthcare issues, however, so this presently remains speculation awaiting confirmation or refutation in future studies. But there was some indication that with childcare, a choice of places to access services may be useful. Joe notes that one of the advantages with Histown is "the childcare's been quite easy to set up, whereas in Hertown it would've been much harder". It is easier, in this case, for distance relaters to take advantage of regional variations in care provision. Yet care is not simply about services provided, or illness needing tending, it is also about looking after someone's wellbeing.

7.11 Although each other's physical care demands are generally few for younger couples, the absence of small caring gestures is heavily felt, as Rebecca indicates:

MARY: What are the things you don't like about it [the distance relationship]?And Ben and Meg appear to affirm the importance of non-verbal ways of connecting and caring:REBECCA: Coming home after a really bad kind of [day] and not getting a hug.

MARY: I, Well do you think that you demonstrate closeness in other ways, rather than through talking?BEN: Yeah, yeah. I'm not a big talker, I'm a big cuddler.

MEG: You're a big cuddler. You are a big cuddler.

7.12 This is some indication that this type of everyday emotional caring and the bodily connection involved is highly taken for granted by cohabiting couples but missed by those apart much more than the disclosure Giddens (1992) has argued is so central to contemporary relationships. Giddens depicts disclosure as being about revealing crucial aspects of one's self to one's partner. Joanne says that disclosure is important, but implies that only in so far as it is part of providing a broader emotional support for each other:

JOANNE: We were just saying when you were getting the coffees, when you were asking us about what care meant that you didn't mention emotional support but that would be important umm for both of us I think, although I definitely, I definitely talk more. I definitely think I verbalise feelings more than you do I think but …

7.13 For both the women and men in this sample, talking and supporting each other seemed to be not so much about baring one's soul but about much more mundane things. Over and over again the people I spoke to talked about the importance of trying to keep connected to each other's routines. They wanted to know, not epic tales of past love and loss but what their loved one was having for dinner or watching on television, or what they had done that day.

MARY: So when you say you like talking about boring things [on the phone]MARGARET: Mmm.

MARY: I mean what's boring things? Just…

MARGARET: Well, like everything that's happened during the day

JOE: Every detail at work.

MARY: Right. Okay.

JOE: [Few inaudible words]. Yeah. Gossip, Umm, work.

MARGARET: About what he said to him and …

JOE: Yeah.

7.14 Meg and Ben indicate that this kind of 'touching base' is crucial in maintaining a connection with each other and preventing them worrying:

MARY: Is that important to you, talking on the phone and keeping in touch?BEN: Yeah. Yeah. I feel a bit funny if I haven't talked to Meg on the phone all day.

MARY: What do you mean funny?

BEN: Well, I don't know? It's not, I don't know, it just feels quite funny.

MARY: Do you ever worry?

MEG: I mean sometimes I get worried if I haven't talked to you [Ben].

BEN: Yeah, yeah that's right. Yeah, yeah, you feel slightly unsettled.

MEG: You don't know what I'm up to, or where I am…

7.15 Both keeping track of each other's routines and talking over problems and 'hassles' were seen as part of something often referred to as 'emotional support'. Such support appeared to be crucial in maintaining a sense of togetherness for couples when they continued to be separated, as Donna also says:

I don't think there is much we wouldn't talk about erm. No I mean we talk about all of it. We talk through stuff as well, we kind of have understandings of things as well as what's happening for us. Y'know so we might talk about what we've done that day because we talk every night so we might y'know, so we might say so what have you done today or I had this, this meeting that was awful and what happened and talk through that meeting or whatever erm or Sam might say I had an awful meeting but let's not talk about it, we'll, let's talk about it at the weekend when I've got my head around what happened or whatever and sometimes because you don't always want to be whinging at each other.

7.16 It seems important to distance relaters to balance their conversations between 'whinging' about trivia and maintaining familiarity with each other's quotidian rhythms. However, something that might help keep distance relationships interesting is that there are different lives to keep up with:

LUCY: But there was a key moment I think where … our younger son er came up to me and he'd been listening to a programme on the radio or been watching a television programme where people umm married people had er been talking about their, the way that their lives umm crossed and the married couples had been saying that they almost never talked to each other and, and he said to us "but when you come home you and dad talk all the time"

MARY LAUGHSLUCY: And that was what made us realise that, that in fact it was, the relation, the arrangements worked actually extremely well because although we were constantly in contact by phone so that I knew what. I knew kind of approximately what was worrying Martin and he know what was worrying me and then we'd come home and we'd just kind of go "puffp " and all it would come out …

7.17 There remain two people, whose individual life courses are not quite as intricately entwined as for those who cohabit. And they are different, in this respect, to other couples at a similar stage of the life course. Yet those in distance relationships also help highlight some of the more taken for-granted aspects of caring within co-habiting relationships and the data looks set to provide some interesting opportunities to reflect further on the kinds of emotional support that couples can provide each other, especially when proximity is lacking.

What Might Distance Relationships Say About Intimacy Across the Lifecourse?

8.1 I will briefly conclude by proposing that distance relationships may illustrate that human bonds are not as frail as Bauman (2003) suggests and can stretch across time and space. Less 'closeness' may provide somewhat greater autonomy for individual partners, without being care free. Indeed, it seems likely that distance makes care difficult and rationalized solutions are often inadequate. This may be true both of large and small acts of caring as they vary throughout the life course. However, distance may allow (or force) care to be distributed amongst a wider group of people, alleviating some of the stresses involved. Nevertheless, those who 'do' distance are likely to find it more difficult at certain points, depending on their gender, age, career, family and care situations. It might be easier for childless women who can sometimes escape the emotion work involved in continual cohabiting, or for younger couples establishing careers. For those with young families it is likely to be extremely complicated. Partners with older parents may find living apart allows them to more easily offer some care (Borrell and Ghazanfareeon Karlsson 2003, Levin 2004). Distance may become a problem if a partner's health fails, and this may be more likely with age. People may shift in and out of distance relationships and other more or less conventional intimate arrangements, thus highlighting the complexity and variability of the contemporary life course. The picture of distance relationships emerging from my research seems to highlight that although people may find structures make it difficult for them to be 'together' with loved ones, being apart from them does not necessarily mean loneliness and despair, nor a permanent departure from more conventional, proximate ways of being intimate. Yet these conventional ways of being intimate are based on romantic narratives of lasting togetherness that often clash painfully with the realities of high rates of relationship breakdown, and the difficulties of combining work and (caring) relationships. And this all has to be endured for longer as increased longevity stretches the life course. Periods apart might be one way in which couples can realistically last the distance.Notes

1 There have been a few other sociological studies of distance relating within the US and elsewhere, but these are small scale, and essentially confirm Gerstel and Gross's (1984) findings (e.g. Anderson and Spruill 1993; Golam Quddus 1992; Farris 1978; Groves and Horm-Wingerd 1991, Schvaneveldt et al 2001). Alternatively work done is psychological, dealing with issues such as adaptation and satisfaction (e.g. Govaerts and Dixon 1988) and often dispensing advice (e.g. Guldner 2003, Winfield 1985).2 This study was interrupted by my relocation to Australia, but I intend to continue the research here.

References

ANDERSON, E.A. and SPRUILL, J.W. (1993) 'The dual-career commuter family: A lifestyle on the move', Marriage and Family Review Vol. 19, pp. 131 - 147.

BALDOCK, C. V. (2000) 'Migrants and Their Parents: Caregiving From a Distance', Journal of Family Issues 21(2): 205-244.

BAUMAN, Z. (2003) Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds. Cambridge: Polity Press.

BECK, U. and BECK-GERNSHEIM, E. (1995) The Normal Chaos of Love. Cambridge: Polity Press.

BELL, M. (2001) 'Understanding Circulation in Australia', Journal of Population Research, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 1 - 18.

BORRELL, K. and GHAZANFAREEON KARLSSON, S. (2003) 'Reconceptualizing Intimacy and Ageing: Living Apart Together' in S. Arber et al. (editors) Gender and Ageing: Changing Roles and Relationships. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

CENTRE FOR SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY IN MINING (2002) 'Key findings from the AusIMM 2001 survey of mining industry professionals' Brisbane: University of Queensland,< http://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/docs/CSRM_rp1.pdf >.

CHANDLER, J. (1991) Women without Husbands. Basingstoke. Macmillan.

EHRENREICH, B. and HOCHSCHILD, A. (editors) (2003) Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy. London: Granta.

ERMISCH, J. F. (2000), 'Personal Relationships and Marriage Expectations: Evidence from the 1998 British Household Panel Survey' Institute for Social and Economic Research Working Paper 2000-27, August. University of Essex.

FARRIS, A. (1978) 'Commuting' in R. Rapoport and R. N. Rapoport (editors) Working Couples. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

FEATHERSTONE, M. and HEPWORTH, M. (1991) 'The Mask of Ageing and the Postmodern Lifecourse' in M. Featherstone, M. Hepworth and B. S. Turner (editors) The Body: Social Process and Cultural Theory. London: Sage.

FOUCAULT, M. (1973) The Birth of the Clinic. London: Routledge.

GERSTEL, N. R. and GROSS, H. (1984), Commuter Marriage: A Study of Work and Family. London: Guildford Press.

GIDDENS, A. (1992) The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies. Stanford: Stanford University Press

GOLAM QUDDUS, A.H. (1992) 'The adjustment of couples who live apart: The case of Bangladesh', Journal of Comparative Family Studies, Vol. 23, pp. 285 - 294.

GOODWIN, J and O'CONNOR, H (2005) 'Exploring Complex Transitions: Looking Back at the 'Golden Age' of From School to Work' Sociology, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 201 – 220.

GOVAERTS, K. and DIXON, D.N. (1988) '…until careers do us part: Vocational and marital satisfaction in the dualcareer commuter marriage', International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, Vol. 11, pp. 265 - 281.

GREEN, A. E., HOGARTH, T, and SHACKLETON, R. E. (1999) Long distance living: dual location households. Bristol: Policy Press.

GREEN, A. E. (1997), 'A Question of Compromise? Case Study Evidence on the Location and Mobility Strategies of Dual Career Households', Regional Studies, Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 641 - 657.

GROSS, H. (1980) 'Dual-career couples who live apart: Two types' Journal of Marriage and the Family, Vol. 42, pp. 567 - 576.

GROVES, M. M. and HORM-WINGERD, D. M. (1991) 'Commuter marriages - personal, family and career issues', Sociology and social research, Vol. 75, No. 4, pp. 212 - 217.

GULDNER, G. T. (2003) Long Distance Relationships: The Complete Guide. Corona, CA: J. F. Milne Publications.

HASKEY, J. (2005) 'Living Arrangements in Contemporary Britain: Having a partner who usually lives elsewhere and Living Apart Together (LAT)', Population Trends, Vol. 122, Winter, pp. 35-45.

HEATH, S. (2004) 'Peer-shared households: Quasi-communes and neo-tribes' Current Sociology, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 161 - 179.

HEATH, S. (1999) 'Young Adults and Household Formation in the 1990s', British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 545 - 561.

HOLLOWELL, P. G. (1968) 'Occupation and Family Life' in The Lorry Driver. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

HOLMES, M. (2004a) 'An Equal Distance? Individualisation, Gender and Intimacy in Distance Relationships', The Sociological Review, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 180 - 200.

HOLMES, M. (2004b) 'The precariousness of choice in the new sentimental order: A comment on Bawin Legros' Current Sociology, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp 251-7.

ILLICH, I. (1975) Medical Nemesis: The expropriation of health. London: Calder and Boyars.

JAMIESON, L. (1998) Intimacy: Personal relationships in modern society. Cambridge and Oxford: Polity Press and Blackwells.

KIERNAN, K. (1999) 'Cohabitation in Western Europe', Population Trends, Vol. 96, pp. 25 - 32.

LEVIN, I. (2004) 'Living Apart Together: A new family form', Current Sociology, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 223 - 240.

MCKEE, L. and MAUTHNER, N. (2000) 'Offshore Work and the Family: "It's Just Something You Live With"', paper presented to Workshop on Commute Employment, New Orleans, December 2000.

RAPOPORT, R. and RAPOPORT, R. (1976) Dual Career Families Re-examined: New Integrations of Work and Family. London: Martin Robertson.

SCHVANEVELDT, P. L., YOUNG, M. H., and SCHVANEVELDT, J. D. (2001) 'Dual-resident marriages in Thailand: a comparison of two cultural groups of women', Journal of comparative family studies, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 347 - 360.

TUNSTALL, J. (1962) 'Fisherman's Domestic Life' in The Fishermen. London: MacGibbon and Kee.

WINFIELD, F.E. (1985) Commuter Marriage. New York: Columbia University Press.