by Jennifer Kent

The University of Sydney

Sociological Research Online, 21 (2), 3

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/2/3.html>

DOI: 10.5153/sro.3860

Received: 10 Jul 2015 | Accepted: 4 Feb 2016 | Published: 31 May 2016

Successful promotion of alternative transport modes needs to be underpinned by better understandings of a seemingly cemented collective preference for private car use. This paper contributes to these understandings and proposes that automobility's dominance can be explained by a series of benefits intimately linked to the car. These benefits extend beyond those associated with utilitarian factors such as saving time. The concept of ontological security is used to propose that attachments to the private car are underpinned by an innate desire for predictability, autonomy and acceptance in modern lives increasingly characterised by insecurity. Empirical evidence on the journey to work in Australia's largest city, Sydney, is applied to examine the way mobility is practised and inform the paper's central proposition.

1.1 The endurance of the private car is often attributed to rational and utilitarian factors, such as individual desires to save time or increase reliability (for example Brownstone and Small 2005). More recently, focus has trended towards the role of the psychological appeal of the automobile, with an emphasis on the way the car fulfils various symbolic and emotional needs (for example Steg 2005; Bergstad et al. 2011). The new mobilities literature has developed concurrent to these more conventional ways of understanding automobility's endurance (Cresswell 2006). This literature often positions the car as instrumental to a socio-technical system, determining not only the way we travel and the spaces in which we travel, but also 'the formation of gendered subjectivities, familial and social networks, spatially segregated neighbourhoods, national images and aspirations to modernity and global relations ranging from transnational migration to terrorism and oil wars' (Sheller and Urry 2006: 209).

1.2 This paper echoes literature on structuration (Giddens 1984), including the revived focus on social practice (Birtchnell 2012, Watson 2012) to tread the line between traditional conceptualisations of automobility. Its proposition is that individual decisions to drive are, in part, underpinned by a culturally inculcated desire for security in modern life which is reinforced through routine practice. The car as a material object of protection, as well as the autonomous and predictable mobility it enables, appeals to a culturally defined, yet intimately individually experienced, desire for security. The concept of ontological security is adapted from its traditional use in sociology and psychiatry to represent this attachment. Empirical evidence on the journey to work in Australia's largest city, Sydney, is applied to examine the way mobility is practised and inform the paper's central proposition.

2.1 Being ontologically secure is having a sense that one knows how the world is and how to be in the world (Laing 2010 [1960]). It provides a secure platform for human agency and flourishing and is often described as a self-maintained protective shell or 'cocoon' used bracket out the uncertainties or risks associated with day-to-day life (Goffman 1959; Giddens 1991).

2.2 Coherency is at the heart of ontological security. The ontologically secure individual maintains a sense of connection, logic and purpose to the different components of his or her life in both space and time. Harre and Gillet (1994) encapsulate the desirability of a coherent life when they write: 'The ideal is a psychological life with the character of an artistic project and not merely a stream of experiences and responses to stimulation' (143). Ontological security is present when an individual can construct a coherent life story which can be told to both herself and others through a biographical narrative (Kinnvall 2004). The individual is attached to the coherent life story (Garfinkel 1967) and will seek to avoid any experience perceived to be at odds with its continuity (Sigel 1989: 459).

2.3 Both exogenous and endogenous influences shape ontological security (Zarakol 2010). Ontological security is something that is individually desired, experienced and negotiated, yet it cannot be extracted from the social environment. The social, technical and economic developments characterising social organisation since the early 1980s have recently been theorised as threatening ontological security. Giddens (1991) (and others) labels these developments 'modernity' and proposes that until its onset, ontological security was not nearly as finely balanced. In the 'pre-modern' world, ontological security was prescribed, if not necessarily guaranteed, by sanctuaries of tradition, religious faith and systems of face-to-face kinship (Giddens 1991). This 'background of being', however, is changing (Thrift 2005: 464) and the maintenance of ontological security is a harder project than it ever used to be.

2.4 While 'modernity' is theorised as characterised by many processes, of particular relevance here is that its accomplice, 'globalisation', has engendered the de-territorialisation of time and space. Events happening elsewhere are localised and 'what structures the locale is not simply that which appears on the scene' (Giddens 1990: 19). Related to the fragmentation of time and space has been its desynchronisation (Urry 2000: 128-129). For example, the slow and steady de-construction of the routines of the working week and the total scattering of time engendered by online media (Moores 2005). Ontological security requires a degree of grounding – it is 'being a whole continuous person in time' and 'having a sense of presence in the world' (Laing 2010 [1960]: 39-41). Time-space de-territorialisation and desynchronisation mean that continuity and presence can no longer be taken-for-granted. As a result, the modern individual is working harder to ground and routinise his or her life story in a time and place respectively (Bauman 2002).

2.5 The concept of ontological security has often been the focus of research on individual experiences of deep-seated disturbances. For example Hawkins and Maurer (2011) applied the concept of ontological security to the study of survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. It has been employed to examine experiences of migration (Hinton et al. 2009; Harney 2011) religious nationalism (Kinnvall 2004) and civil war (Steele 2005). There is also emergent study of ontological security, however, as increasingly under threat in a more everyday context. For example, the concept has been used to represent attachments to the home. Here, home is understood to support ontological security through provision of the continuity of a stable foundation around which individual and collective identities can be shaped and day-to-day life routinised (Dupuis and Thorns 1998; Saunders 1989; Kearns et al. 2000; Hiscock et al. 2001). The literature on the relationship between mobility and ontological security is vague. This is surprising given recent conceptualisations of the car as an increasingly important place for 'dwelling' and automobility as important for personal autonomy (Laurier and Dant, 2012) and broader literature highlighting the tenuousness of autonomy and privacy in modern life (for example Bauman 2010). An exception is an extension by Hiscock et al. (2002) of their application of the concept in the home to the private car. They propose that ontological security is comprised of protection, autonomy and prestige and seek to examine how cars can bestow these sensations upon their owners. The car here, however, is very much treated as an object, with little consideration given to the idea that it is the autonomous mobility afforded by the car that supports ontological security. Further, although Hiscock et al. (2002) use empirical means to support their propositions on ontological security by drawing on data from interviews, they admit throughout their various studies to making no attempt to evaluate its role in modern life, citing Saunders to state that ontological security is 'difficult to define [and] even more difficult to operationalise' (Saunders 1989 in Hiscock et al. 2001: 52). The subjectivity inherent to ontological security renders its quantification unhelpful, if not impossible. The concept of ontological security as applied to automobility does, however, require a more systematic elaboration than is found in the work of Hiscock et al. (2002). The attempt here, therefore, is to break the concept down into operational themes which can then be used to explore this paper's central proposition that automobility's appeal is its function as ontologically securing in modern life.

3.1 The data presented here is a selection of that gathered for a larger project analysing resistance to transport alternatives to the private car (Kent 2013a). The primary method used for data collection was a series of semi-structured in-depth interviews.

3.2 As a low-density city characterised by a dispersed geography of employment, Sydney's 4.6 million residents are highly reliant on the private car for day-to-day mobility (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011). This reliance endures in the face of attempts to regulate and plan for the use of other modes, and, in some cases, the availability of time competitive alternative transport. Accordingly, this study has an intentional focus on those who continue to drive in the face of expedient alternatives. Using a systematic process of trip substitution analysis (detailed in Kent 2014), a group of people were identified who could use alternative transport to get to work in the same amount of time it currently takes them to drive. These people then participated in a series of in-depth interviews where deeper attachments and motivations for private car use were explored.

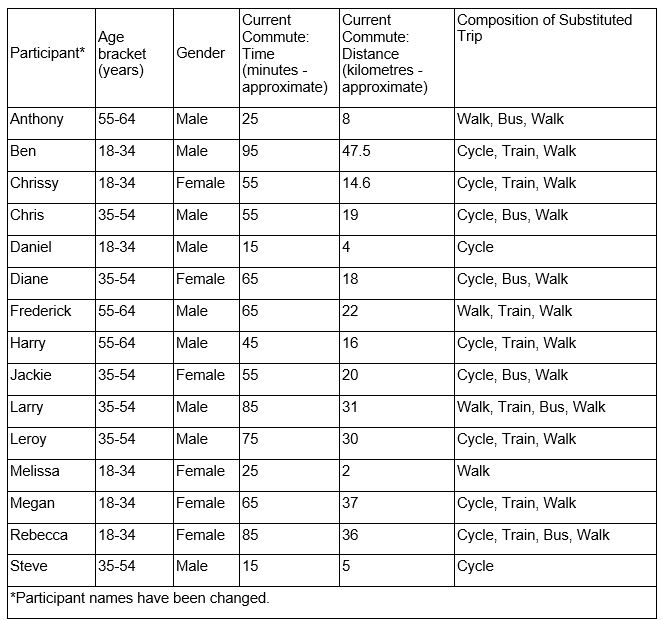

3.3 In total 15 people participated in 30 interviews lasting between 55 and 70 minutes. Some participant details are contained in Table One. As per the method employed for purposive sampling, all participants consistently travelled to their place of full time employment as a single occupant of a private vehicle. All either owned outright or were in the process of paying off their own cars. All lived in households where the number of licenced drivers matched the number of cars at home. There was no pattern to the type or size of cars owned by each participant. Some participants took obvious pride in their cars while others struggled even to name their car's make and model.

3.4 Interviews were conducted by the author. Participants were first asked to describe the way they drive to work, including details on the specific route or routes they take. They were asked to talk about the traffic en route, as well as the way they occupy their time in the car. The interview progressed to ask participants to describe in detail what they do at work, their home life and the structure of their typical day. Participants were then also asked about their aspirations in life. They were encouraged to speak without restriction about the things that were important to them, exploring ideas they had about where they'd like to be in the future, how they work towards these goals, as well as their priorities, values and special interests. By opening with an interest in driving, progressing to frame this practice with details on other routines and insights into each participant's goals and values, a layered appreciation of the way the use of the car for the journey to work is embedded in each participant's lifestyle could be developed.

3.5 The second interview was conducted between six days and two weeks after the first. It was purposefully more structured. At the beginning of the second interview, participants were asked about the type of car they drove, the age at which they'd obtained their drivers' licence and the basic travel patterns of their household. The alternative trip developed from the trip substitution analysis previously described was then outlined in detail. The participant's reactions were subsequently explored. Potential benefits and barriers relevant to the substitute trip were discussed, both entirely as perceived by the participant.

3.6 With permission from participants, interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder. Systematic coding of all data from interviews using QSR NVivo 9 was undertaken at the completion of each interview. Methods for coding the transcripts involved constant comparative analysis of data against emergent themes (Charmaz 2006) and used topic, initial, primary and axial coding (Saldaña 2009).

|

| Table 1. Selected Participant Characteristics |

4.1 Analysis starts purposefully with the theme of time in an effort to explore each participant's response to the alternative trip prescribed through trip substitution analysis.

4.2 Study participants conceptualised time in a variety of ways - time waiting, time lost, time saved, time given, time taken, time spent. First and foremost, however, participants treated time as a currency of high value and something that should not be wasted. Ben, for example, described the way he cherishes spare time to spend with his six week old baby boy:

Ben: I guess, every little minute that you get now, even if it's just sitting down talking, sitting down watching TV together, sitting down with the boy, just holding him sort of thing, it's just precious. Time is precious.

4.3 As each participant was introduced to his or her alternative trip, it was emphasised that it would take the same amount of time as their existing car-based trip. Contradicting utilitarian models of transport behaviour, which stress time as a key determinant of transport mode choice (Milakis et al. 2015), participants tended to cite their preference for the private car as a way to administer and control time, rather than as a way to save it.

4.4 Regardless of efforts to 'remove' time's impact, it continued to feature strongly in the way the participants spoke about their choice to drive. It was not, however, that the car was necessarily perceived as faster than alternative transport, it was that the participants perceived time taken on trains, buses, or walking and cycling, as more of an investment, more frustrating, less comfortable and more disempowering than the time they spend in their car. This persisted to the extent that some participants even indicated they did not mind if driving to work actually took more time than the use of alternative transport. Frederick compared his 65 minute alternative trip with the time it currently takes him to drive:

Frederick: I remember, a long time ago, I used to catch the train to work. It was really busy, people always trying to find their way, and people trying to squeeze in, sometimes the door shuts too early. ..So then I think about taking my car, even if it's about 1 hour, 1 hour 15 minutes, I don't care. I think, ah, it's fine I have the air conditioning, I listen to a bit of music, best of the 80s, the news from ABC.

4.5 If the need to spend excessive time on the alternative transport journey was not a primary barrier to the use of alternative modes, what remains for this study's participants to justify the drive? Several themes emerged through the process of data analysis to offer answers to this question. To varying degrees these themes combined to substantiate much of the existing research on transport practices as reviewed briefly at the beginning of this paper. These themes include the way automobility is sustained through routine practice and have been reviewed in detail in Kent 2014a and Kent 2014b. Delving deeper into these themes by placing them against a background of participant values, goals and practices, a clear story emergent from the data was that automobility is used to secure many of the things that matter in modern life. For study participants, the autonomous mobility afforded by private car use, is a defining element of how to 'be' in the world - the private car facilitates and protects their way of navigating and experiencing life. Further coding and consideration of existing literature demonstrated that this enabling and protection can be conceptualised as the maintenance of ontological security.

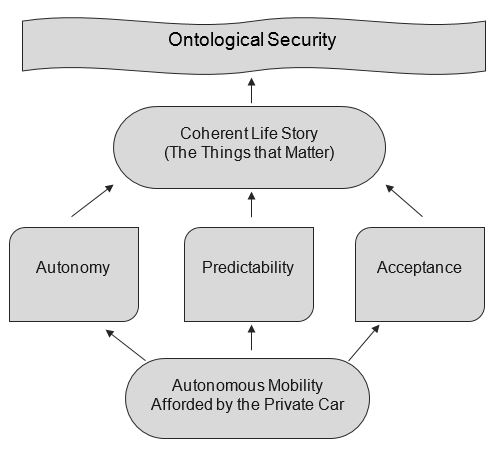

4.6 Informed by the empirical data collected and analysed as described above, as well as a review of existing literature on the concept, this paper proposes a model of ontological security as a coherent life story that is supported by three key components:

4.7 This relationship is expressed in figure one.

|

| Figure 1. A Model of Ontological Security |

4.8 These three key components were identified as required to give life a sense of coherency as described by this study's participants. The conceptualisation of ontological security as made up of three components supporting a coherent life story and supported by automobility was developed subsequent to a complex process. This process adhered to a constructivist grounded theory methodology involving five separate stages of coding placed against a review of existing literature (after Charmaz 2006). It has been described in detail elsewhere (Kent 2013a). Of relevance, however, is that the autonomous mobility afforded by the private car was consistently positioned as imperative to each of the three components which were subsequently identified as intricately linked to the pursuit of ontological security. This paper now returns to the data to explore these components and unpack the way automobility is used to support them.

4.9 A key component of ontological security is confidence in the continuity of the social and material environment (Wakefield and Elliott 2000). This sense of predictability is not only important in that it is empowering, but also because it promotes the idea of living a life that has a future focus and allows for forward planning (Davies 1997). Such projection towards the future signals that the actions and behaviour involved in living have meaning. Automobility can support predictability in a number of ways.

4.10 Predictability is developed from routine. Routines provide the constancy in which identity and agency can flourish. They inoculate the individual against existential anxiety of the unknown and allow one to get on with living life (Giddens 1991: 39).

4.11 This study's participants spoke about the many different routines that make up their day-to-day lives and the car was described as a place for their performance. Parking, route choice, phone calls, the application of make-up, listening to specific radio programs, were all things routinely accomplished in the space of the car and during the time granted by the commute. Indeed, transport practices are regularly conceptualised as cemented by habit (Bissel 2014), and for this study's participants, driving to work is a routine in itself. Diane and Frederick, for example, both describe how the practice of driving to work has been demoted to the realm of the subconscious rather than something they need to think about prior to embarking on each trip:

Diane: It's like [pause] I think it's just the ritual of it [driving to work], it's just what I do. You know, you get in the car, you go to work [pause] yeah, that's it.

Frederick: For me driving to work is just something I do. I don't think about it and it doesn't bother me at all. I like it, I don't want to have to think about it every day, you know.

4.12 Aside from providing a space and time for the performance of predictable routines, there are other ways the private car commute facilitates predictability. Automobility plays a key role in the maintenance of predictable home and work environments. Being able to drive to work expands the ability for people to change their employment location without moving home, or to move home without having to change employment. Leroy for example was made redundant from his city job, which was a 15 minute bus ride from where he lives with his wife and two young children. In seeking new employment he had the choice of accepting a lower- paid position in the city or a higher-paid position requiring a 75 minute commute each way. The fact that he can drive to work enabled him to take the pay rise while simultaneously maintaining a stable home life by not having to move his family. He openly admits that this decision to accept the car-dependent job enabled him to have a second child because the pay rise allowed his wife to take time off work:

4.13 The way that this ability to maintain a stable home and work life fosters empowerment is further discussed below. It is relevant here because it demonstrates the way automobility makes possible the stability of a predictable work and home environment - a predictability that, for many people, is supportive of ontological security.

4.14 Participants expressed a collective interpretation of normality. When explaining why she had bought a four bedroom house, over 65 minutes from her work, Megan, for example, says that it 'seems to be what you do':

4.15 At a very practical level, the car supports cultural constructions and interpretations of normalcy. For example, private car use allowed Megan to purchase a larger house in a more affordable area than the area in which she works. This purchase was seen as a way to move 'up to the next phase of life' (Megan). This demonstrates the way being 'auto-mobile' has complex connections to living life the way it should be lived. This includes day to day constructions of the normal travelling subject (discussed below), but extends to interpretations of a life lived in harmony with the expectations of family and society. For this study's participants, the private car secures a quintessentially normal path through life.

4.16 In summary, predictability is important to the pursuit of ontological security. The car supports routine and predictability on many levels. Demoting the need to be mobile to the background of consciousness allowed this study's participants to concentrate on tasks perceived to be more important or relevant. It also provides a physical place for routines to be constructed and protects other routines structured around place of residence and place of work. Many of these routines are strongly connected to culturally ingrained ways of living in modern life and their practice cements private car use. Automobility provides a way of not only being mobile, but also attaining other life goals, such as owning a house and raising a family. These are goals that are 'normal' and the well-worn pathways to their attainment are familiar. The sense of mastery, or 'knowing', that comes from routine and predictability relates directly to autonomy and control and discussion now turns to this component of ontological security.

4.17 The autonomy to learn, develop and create is required for ontological security, as is the autonomy to take control (Mitzen 2006). Perhaps ironically, this autonomy is just as necessary to the maintenance of ontological security as the habits and routines that make up predictability (Little 2001).

4.18 Mastery, or 'knowing what to do', is a key component of ontological security, and automobility supports this in a number of ways. Firstly, automobility, for some, is fundamental to modern ways of working that are dependent on flexibility and reliability. For this study's participants, gainful employment is described as integral to giving life coherency, including supporting material pleasures, a healthy family, and a sense of respect and self-worth. Participants regularly described, however, that the work environment was competitive, and that their employment was contingent on them being flexible and available. Steve, for example, is often required to accommodate the demands of different time zones and businesses that operate '24/7':

4.19 For Anthony, flexibility was used as a type of currency in his job as an architect:

4.20 It is the car that enables spur-of-the-moment client visits, unpredictable workflows and the 24-hour availability required to master the modern occupation. This mastery is a platform from which to attend to many other things that matter in life, including supporting family and indulging in things that bring happiness.

4.21 Automobility, by definition, is having freedom. It is about being autonomously mobile - able to move independently, and to come and go where and when one wants (Dowling and Kent 2013). Barriers to the uptake of alternative transport conceptualised as a loss of freedom and control have been explored in detail by previous research. The car's association with freedom in cultural texts such as film, music, popular literature and advertisements has been widely reviewed (Miller 2001; Dowling and Simpson 2013), as has the link between capitalistic structures of production, automobility and individual freedom (Featherstone et al. 2005; Freudendahl-Pedersen 2012). For participants in this study, freedom from timetables, fixed routes and unwanted social interaction were all implicated as valued elements of car use.

4.22 This appreciation of freedom was extended to encompass not only freedom of movement, but freedom to choose places in which to be immobile. Larry, for example, explains how important it is to him to have autonomy over where he lives:

4.23 The car is obviously then required to support this freedom because it allows Larry to bridge the gap it creates between home and work. In Larry's case, this gap is an 85 minute drive each morning and evening.

4.24 Freedom is a concept notorious for its ability to assume multiple interpretations (Berlin 1969). For example, it can mean both 'freedom to and freedom from' (Kearns et al. 2000: 120, emphasis added). While the private car provided participants the opportunity to master the demands of valued but often stressful employment, it also allowed for escape from these demands when possible and appropriate. Confirming a raft of previous research (see for example Mann and Abraham 2006), participants in this study described the way the car commute provides a space and time to escape - a place of freedom from. The car commute was labelled a 'time to zone out' (Chrissy), 'good me time' (Jackie), and a place to 'get out of the mindset of being at work' (Dan). The car also provides a space that is personal and personalised, a place we can own ('like a cat' ? Frederick) and a place where we are not forced to interact.

5.1 The final component of ontological security is acceptance. Ontological security needs the self to be viewed positively in regards to others (Hiscock et al. 2002: 120). It is reflexively defined, meaning the individual pursues it in accordance with his or her interpretation of what society defines a secure life to be. While the individual's interpretation is key to ontological security in that it promotes autonomy, rationalisation of this interpretation with the social is similarly fundamental (Laing 2010). It is this explicit conceptualisation of ontological security as a product (in part) of seeking social acceptance that gives the concept a deeper connection to collective social and cultural patterns than the traditional psychological concepts related to the exogenous and endogenous development of the individual.

5.2 The role of automobility in satisfying the need for acceptance is exhibited in a number of ways, including the desire for a sense of belonging and approval, the pursuit of prestige and status, as well as the intrinsic need to maintain a sense of self-acceptance.

5.3 An irony of human nature is the simultaneous yearning for autonomy and sense of belonging. Bauman refers to this as 'a dream of belonging and a dream of self-assertion' (2010: 64). Study participants demonstrated a need to belong and interact with other people and the car facilitates this in a number of ways.

5.4 Firstly, in a purely utilitarian sense, automobility enables people to negotiate space and time to physically be with other people. For example, many participants had the option to work from home, however none of those with the option accepted it on a regular basis because they had an appreciation for the sociability of physically being in the office.

5.5 In a more emotional sense, the car facilitates belonging in that to drive is a socially accepted way to be mobile. Many participants felt that not to drive is to be 'the other' and in the extreme sense a subject of pity. Larry, for example, describes feeling 'sorry for people [pause] waiting in the hot sun or the pouring rain, waiting for buses'. Harry also associates the use of alternative transport with abnormality:

5.6 Related to this is the way participants felt that the car, as both a space of shelter and a mode of transport, maintains a certain appearance. Being sweaty and looking strange in sporting attire, for example, were suggested to be preludes to being rejected in some way, and participants often expressed the idea that the use of alternative transport would impact negatively on their physical presentation.

5.7 Diane's emotive reaction is indicative:

5.8 Participants described the importance of gaining the approval of others, often identified as family and work colleagues. For example, for Anthony, the ability to impress clients by bending his time around their demands gives him 'kudos', for Rebecca, staying late at work was a way to 'to feel valued'. The car is used as a way to gain approval by enabling people the flexibility to bend themselves around the demands of others. Participants consistently indicated that the flexibility and reliability inherent to automobility were integral to the establishment of rapport and maintenance of reputation:

5.9 Self-pride is intrinsic to the individual's capacity to maintain ontological security (Giddens 1991: 66). In short, one needs to accept oneself if one is to be ontologically secure. This sense of pride is exhibited through routines of self-nurture and self-care. The ontologically secure individual seeks to minimise discomfort when its experience is not related to something that is important. For example, many participants had returned to part-time study with the aim of promotion at work. The 'discomfort' of studying part-time and working full-time, including late nights and weekend workshops, is endured because getting a promotion at work is important. If discomfort has no relationship to what one is trying to achieve in life, then it makes sense to avoid it. This is nicely expressed by Frederick:

5.10 The concept of car-comfort, demonstrated to be an extremely motivating factor for automobility (as reviewed in Kent 2014), can be conceptualised as related to a deeper drive to nurture the self. Driving the car, avoiding the rain and hot weather, the sweaty people on the train and the danger of riding a bike, are all practices of self-nurture. Similarly, the way that the car is perceived as the 'normal' thing to do is also related to a desire to look after the self by avoiding the pain associated with social rejection or simply being 'different'. A human desire to nurture and protect the self is a very natural yet also culturally inculcated response. For some, driving is a practice of self-nurture, and recognition of this deepens existing conceptualisations of the extent to which automobility is embedded in modern life.

5.11 This paper has thus far described being ontologically secure as having a sense that one knows how the world is and how to be in the world. Ontological security is conceptualised as comprised of predictability, autonomy and acceptance, all of which underpin the pursuit of things that matter in life and provide a sense of how the world is. Discussion now turns to the value and implications of such a conceptualisation on future research on mobility practices.

6.1 The association of private car use with aspirations such as predictability, autonomy and acceptance is not necessarily a unique contribution to scholarship on automobility's endurance, and attempts have been made to position this study's findings relative to each component within the context of a burgeoning base of existing transport literature. The point here is that, taken together, these pursuits can be conceptualised as the need for ontological security – a need to have 'a centrally firm sense of [one's] own and other people's reality and identity' (Laing 2010 [1960]: 39).

6.2 There are three ways a conceptualisation of private car use as ontologically securing furthers existing literature on the automobility's endurance.

6.3 First, linking automobility to ontological security provides a more embracive way to conceptualise attachments to private car use, demonstrating a framework to blur the false dichotomies of rational instrumental/symbolic affective motives that continue to filter through transport research and policy making. This characteristic of the way the private car is used in modern society cannot necessarily be neatly positioned as having symbolic or utilitarian association. It is simultaneously perceived and practised, related as much to rational decisions to manage time as to emotional yearnings for freedom, control and social acceptance.

6.4 Second, as a culturally refined, yet individually negotiated concept, ontological security transcends further dichotomies related to the relative impact of structure and agency on mobility practices. This is an interesting area of asynchrony between utilitarian and psycho-social approaches, which locate mobility as an outcome of the actions of individual agents, and the new mobilities paradigm, which places more emphasis on the way systems shape transport practice. Shaped by both structure and agency, mobility as ontologically securing demonstrates how both the systems of mobility (structure) and the actions and motivations of the individual (agency) influence time-space negotiations. Transport behaviour is shaped by the individual, the individual is shaped by the system and so on, and the concept of ontological security provides an interesting demonstration of this.

6.5 Third, the conceptualisation embeds attachments to private car use in broader explorations of the notion of modernity. This enables a framework for development of a clearer understanding of the depth to which automobility is entrenched in ways of negotiating the complexities of modern life. This paper's introduction of the concept of ontological security highlighted scholarship suggesting the ontological project is more finely balanced today than it ever has been in the past, with the concept increasingly applied to explanations of social ordering in more mundane contexts. These suggestions draw on theorisations of the deterritorialisation of time and space engendered by grand processes such as globalisation, as well as the practical realities enabled by technology. The analysis presented here demonstrates the way automobility is used by some to define, negotiate and somehow ground lives lived in the face of increasing uncertainty that is characteristic of modern life. These uncertainties relate to demanding work environments, and the enduring pressure to pursue and support the things that matter in life, including family and material gain. This positioning adds to increasingly common calls, in both scholarship and practice, for mobility to be viewed as more than just a matter of accessibility.

7.1 This research explores preferences for automobility to demonstrate the way private car use is deeply embedded in modern life. It uses the concept of ontological security to represent attachments to automobility as deeper than traditional utilitarian and psycho-social approaches to transport behaviour have proposed. The car as a time saving device is perhaps only as relevant as the role automobility plays in fulfilling individual interpretations of cultural notions such as predictability, autonomy and acceptance in everyday life.

7.2 This study has several limitations which need to be acknowledged. First, as is characteristic of qualitative research (and, arguably, also with quantitative research (Sofoulis 2009)), the conclusions presented here are not necessarily representative. They may or may not apply to the millions of others whose collective journeys to work by car create the problems associated with automobility. Given the complexity of automobility and the implications this has for the uptake of alternative transport, however, it is questionable whether reasons for its persistence can ever be generalised. The multiplicity of ways the private car supports modern life is undeniably difficult, if not impossible, to quantify. An inability to calculate and measure, however, is not a valid reason to eschew an area of research that is in dire need of deeper understandings. These understandings can only be developed in conversation with those who, each weekday morning, drive their car to work.

7.3 Just as these findings are not necessarily representative, nor are they necessarily unique. Beyond drawing pictures of population subsets based on various socio-demographic profiles, the persistence of the practice of driving to work suggests that the study's participants are not atypical. There are many others who continue to drive to work each day in the face of increased congestion and awareness of the environmental and health harms associated with the practice of automobility. Some of these people may also be aware that the same trip by bus, train, bike or foot might be quicker for them from time to time. There are, therefore, potentially many others using automobility as security in a society and culture that is increasingly characterised by uncertainty.

7.4 Second, caution needs to be used in any attempt to apply this specific conceptualisation of ontological security to studies on alternative transport users. Of course there will be many people who experience predictability, autonomy and acceptance from the use of alternative transport. For example, for some, the daily rhythms of a predictable bus trip may bring comfort, the ability to master a complex subway system may foster autonomy or the ride to work alongside familiar bodies on bikes may cultivate a sense of belonging. This observation, however, adds very little value to the task of shifting the transport practices of those currently secured by automobility. The conclusion of this study is not that the practice of automobility is any more, or less, able to support ontological security than alternative transport.

7.5 There are a number of broad implications of this conceptualisation of automobility as ontologically securing for policies promoting alternative transport.

7.6 The most obvious policy implication is that any approach to the promotion of alternative transport based primarily on making it time competitive is inherently flawed. This research suggests that people are not as interested in saving time as they are in keeping life predictable, retaining autonomy and conserving the energy they perceive as wasted on the discomfort associated with alternative transport use. This finding confirms and deepens existing understandings of transport behaviour which have long recognised the myth that transport is a product of utility alone (see for example Jain and Lyons 2008).

7.7 A second policy implication relates to the finding that the car is unlikely to disappear from the lives of suburban office workers in traditionally car-dominated cities. 'Of course the car is here to stay' (Freund and Martin 2009, 477). This includes maintaining some space for road building and the provision of parking in transport planning. It will inevitably mean planning for people to drive less, through provision of alternative transport infrastructure. It may also mean the further affirmation of a place for the car that is not privatised, such as through car sharing programs. However there will need to be continued provision for people to drive with less impact, using alternative fuels and technologies. In addition, this finding gives mandate for better integration of automobility with alternative mobility planning.

7.8 A final and overarching policy implication is that greater attention needs to be paid to the way automobility exists not only in other structures of political economy, but also in the lives of ordinary, everyday people. For many people, automobility supports the things that matter in modern life, including family and work. The way that security is felt as increasingly under threat, and the implications of diminished security in other areas of life, such as housing and employment, need to be considered in the planning and promotion of alternative transport. Further, planning and policy relating to housing and employment need to consider transport as more than just a matter of accessibility. For many people a shift to alternative transport is an imposition on deep-seated notions of freedom and entitlement as much as it is on their time, income and personal space.

AUSTRLIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS (2011) Census of Population and Housing - Census Data by Location. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

BAUMAN, Z. (2002) Society Under Siege. Polity Press, Cambridge.

BAUMAN, Z. (2010) 44 Letters from the Liquid Modern World. Polity Press, Cambridge.

BERGSTAD CJ, Gamble A, Hagman O, Polk M, Garling T and Olsson L E. (2011) Affective-symbolic and instrumental-independence psychological motives mediating effects of socio-demographic variables on daily car use. Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 19, p. 33-38. [doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.11.006]

BERLIN I. (1969) Four Essays on Liberty. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

BIRTCHNELL T. (2012) Elites, elements and events: Practice theory and scale. Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 24, p. 497-502. [doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.020]

BROWN W S. (2000) Ontological Security, Existential Anxiety and Workplace Privacy. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 23, p. 61-65. [doi:10.1023/A:1006223027879]

BROWNSTONE D and Small K A. (2005) Valuing time and reliability: Assessing the evidence from road pricing demonstrations. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, Vol. 39, p. 279-293. [doi:10.1016/j.tra.2004.11.001]

CHARMAZ K. (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications, London.

CRESSWELL T. (2006) On the move: mobility in the modern western world. Routledge, London.

DAVIES M L. (1997) Shattered assumptions: Time and the experience of long-term HIV positivity. Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 44, p. 561-571. [doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00177-3]

DOWLING R and Kent J L. (2013) The Challenges of Planning for Autonomous Mobility in Australia, proceedings of the State of Australian Cities Conference, Sydney, December, 2013.

DOWLING R and Simpson C. (2013) 'Shift?the way you move': reconstituting automobility. Continuum, p. 1-13. [doi:10.1080/10304312.2013.772111]

DUPUIS A and Thorns D C. (1998) Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security, Sociological Review, Vol. 46, p. 24-47. [doi:10.1111/1467-954X.00088]

FEATHERSTONE M, Thrift N and Urry J. (2005) Automobilities. Sage Publications, London.

GARFINKEL H. (1967) Studies in ethnomethodology. Polity Press, Cambridge.

GIDDENS A. (1984) The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press, Oxford.

GIDDENS A. (1990) The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

GIDDENS A. (1991) Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford University Press, Stanford.

GOFFMAN E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor Press, New York.

HARNEY N. (2011) Migrant strategies, informal economies and ontological security: Ukrainians in Naples, Italy. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Vol. 32, Iss. 1.

HARRE R and Gillett G. (1994) The Discursive Mind. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

HAWKINS R L and Maurer K. (2011) 'You fix my community, you have fixed my life': the disruption and rebuilding of ontological security in New Orleans. Disasters, Vol. 35, p. 143-159. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01197.x]

HINTON D E, Hinton A L, Pich V, Loeum J R and Pollack M H. (2009) Nightmares Among Cambodian Refugees: The Breaching of Concentric Ontological Security. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry, Vol. 33, p. 219-265. [doi:10.1007/s11013-009-9131-9]

HISCOCK R, Kearns A, MacIntyre S and Ellaway A. (2001) Ontological Security and Psycho-Social Benefits from the Home: Qualitative Evidence on Issues of Tenure. Housing, Theory and Society, Vol. 18 p. 50-66. [doi:10.1080/14036090120617]

HISCOCK R, Macintyre S, Kearns A, and Ellaway A. (2002) Means of transport and ontological security: Do cars provide psycho-social benefits to their users?. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, Vol. 7, p. 119-135. [doi:10.1016/S1361-9209(01)00015-3]

JAIN J, & Lyons G. (2008). The gift of travel time. Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 16, No. 2, p. 81-89. [doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.05.001]

KEARNS A, Hiscock R, Ellaway A and McIntyre S. (2000) 'Beyond four walls'. The psycho-social benefits of home: Evidence from West Central Scotland. Housing Studies, Vol. 15 p. 387-410. [doi:10.1080/02673030050009249]

KENT J L. (2013a) Secured by automobility: why does the private car continue to dominate transport practices? PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales.

KENT J L. (2014a) Driving to save time or saving time to drive? The enduring appeal of the private car. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, Vol. 65, p. 103-115. [doi:10.1016/j.tra.2014.04.009]

KENT J L. (2014b) Still Feeling the Car – the role of comfort in sustaining private car use. Mobilities. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2014.944400. [doi:10.1080/17450101.2014.944400.

]

KINNVALL C. (2004) Globalization and religious nationalism: Self, identity, and the search for ontological security. Political Psychology, Vol. 25, p. 741-767. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00396.x]

LAING R. (2010 [1960]) The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

LAURIER E, Dant T. (2012) What We Do Whilst Driving: Towards the Driverless Car in Mobilities: New Perspectives on Transport and Society Eds GRIECO M, Urry J. Ashgate Publishing Group, Farnham, p. 223-240.

LITTLE J M. (2001) Communitarianism, Autonomy, Ontological Security and Human Flourishing: An Exploratory Essay. Centre for Values, Ethics and the Law in Medicine, University of Sydney.

MANN E and Abraham C. (2006) The role of affect in UK commuters' travel mode choices: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. British Journal of Psychology, Vol. 97, p. 155-176 [doi:10.1348/000712605X61723]

MILLER D. (2001) Car Cultures. Berg, Oxford.

MITZEN J. (2006) Ontological security in world politics: State identity and the security dilemma. European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 12, p. 341-370. [doi:10.1177/1354066106067346]

SALDAA J. 2009 The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications, London.

SAUNDERS P (1989) The meaning of 'home' in contemporary english culture. Housing Studies, Vol. 4, p. 177-192. [doi:10.1080/02673038908720658]

SHELLER M and Urry J. (2006) The new mobilities paradigm. Environment & Planning A, Vol. 38, p. 207-226. [doi:10.1068/a37268]

SIGEL R. (1989) Political learning in adulthood. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

SOFOULIS, Z. (2009) Social Construction for the Twenty-first century: A Co-Evolutionary Makeover. Australian Humanities Review, Vol. 46.

STEELE B J. (2005) Ontological security and the power of self-identity: British neutrality and the American Civil War. Review of International Studies, Vol. 31, p. 519-540. [doi:10.1017/s0260210505006613]

STEG L. (2005) Car use: lust and must. Instrumental, symbolic and affective motives for car use Transportation Research Part a-Policy and Practice, Vol. 39, p. 147-162. [doi:10.1016/j.tra.2004.07.001]

THRIFT N. (2005) From born to made: technology, biology and space. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 30, p. 463-476. [doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00184.x]

URRY J. (2000) Sociology Beyond Societies: Mobilities for the 21st Century. Routledge, London.

WAKEFIELD S and Elliott S J. (2000) Environmental risk perception and well-being: effects of the landfill siting process in two southern Ontario communities. Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 50, p. 1139-1154. [doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00361-5]

WATSON, M. (2012) How theories of practice can inform transition to a decarbonised transport system. Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 24, p.488-496. [doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.04.002]

ZARAKOL A, (2010) Ontological (In)security and State Denial of Historical Crimes: Turkey and Japan. International Relations, Vol. 24, p. 3-23.

Author: So in a way it [working outside of the city] allowed [Leroy's wife] to stay at home at this time, whereas if you had have been less flexible, like about where you work, and taken a pay cut to work in the city she might not have been able to do that?

Leroy: Yeah, yeah you're right. I mean, to be honest we would have had to think harder about the second child. We are set up for a certain lifestyle and you build your lifestyle around your income.

Predictability as normality

Megan: We were just moving up to the next phase of life I guess, we had our little three bedroom house and we renovated it and did it up, that seems to be what you do when you first buy a house, and then you sort of move up and on.

Autonomy

Autonomy as mastery

Steve: The whole proviso is that we are here to support the stores. If the stores are not selling we don't have a job, all those systems, we need to make sure they're going 24/7.

Anthony: See I can get a call during the day and it's like 'no problem I'll come and see you this afternoon', you know, or 'whatever time you like'. And I like that? you get a lot of gratitude and kudos for that from the people.

Autonomy as freedom

Author: So, you said the cost is something that prevents you from thinking about public transport?

Frederick: That's why. Apart from the independence, to say, well, what time do I have to leave to go to catch the train in the morning.

Author: Have you ever considered moving closer [to work]?

Larry: No, I live where I want to live and I work where the work is. I don't understand people that go 'this is where I'll work [and] this is where I'll buy a house' because it might not be the area they want to live in.

Freedom from?

Acceptance

Acceptance as a sense of belonging

Harry: When I was at uni, I had this professor you know, who used to cycle, and I always thought he was a bit nutty, you know, 'why ride a bicycle?!'

Diane: The hair! There is no way I would wear a bike helmet and you know have your hair like that, [pause] no that wouldn't happen for me and, oh, the makeup! [laughs]. But seriously, how I go to work is not conducive to riding a bike. Like, what I wear, makeup, hair, everything. We are a corporate here.

Acceptance as a sense of approval

Author: Why do you drive?

Larry: Because [pause] well, I'd have to be at Parramatta at a particular time to get the shuttle bus and leave at a particular time to get it back and I find that restrictive if something's going on and I need to keep working. It's either beg, borrow or steal a cab charge to get back to Parramatta or say, 'no sorry, can't keep working, I have to go home'. It gives me the flexibility and flexibility is important. It's a bit rude too, to stand up half way through a meeting and say 'no, I have to catch a train', I don't want to do that to people. They would be flexible for me if I needed it.

Self-acceptance through self-nurture

Frederick: I could, in terms of viability, it [alternative transport] would get me to work. But in terms of comfort, I really prefer the car. I am being selfish because I am in my car and on my own. But I think that, [pause] in life, we have so many stressful situations. And it is not stressful for me to drive.

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References