by Nadine Arnold and Raimund Hasse

University of Lucerne; University of Lucerne

Sociological Research Online, 20 (3), 10

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/20/3/10.html>

DOI: 10.5153/sro.3734

Received: 19 Jan 2015 | Accepted: 12 Jun 2015 | Published: 31 Aug 2015

Voluntary standards are a ubiquitous phenomenon in modern society that has recently started to attract sociologists' profound interest. This paper concentrates on formal standardization over the long term and seeks to understand its effects on the coordination of an organizational field. Using an institutional approach we see standards as a form of governance that can be analytically distinguished from other modes of coordination, such as markets and hierarchical organizations. To empirically ground our understanding of formal standards' consequences on field-level governance, we conducted a case study of the historical development of the Swiss fair trade field since the 1970s. Evidence used in this case study is drawn from 28 expert interviews, documentation and fair trade standard documents. While a formal set of voluntary standards was absent in its early development, in 1992 fair trade organizations started to use written standards as a means of achieving their objectives. Paradoxically, the introduction of a rational standardization system has led to escalating governance structures in the field. In the long run the launch of formal standards has caused more organizations, more markets, and even more standards. The use of standards as a means of creating differentiation instead of generating uniformity is thereby seen as the main reason for increased coordination demands. As a consequence, this article highlights standards' potential to boost additional governance efforts and directs attention to the mutual enforcement of distinct modes of coordination.

1.1 We live in 'a world of standards' (Brunsson & Jacobsson 2000) and modern society seems to be crowded by voluntary standards that permeate distinct social spheres, such as medicine, business, sports, education as well as agriculture or arts. Hence standards and standardization are a ubiquitous phenomenon that has transformed from an underdeveloped and often underestimated subject of investigation to a vibrant topic in sociological literature over last few years (Busch 2011; Higgins & Larner 2010; Lampland & Star 2009; Ponte et al. 2011; Timmermans & Epstein 2010). In comparison to scholars of the sociology of conventions that grapple with informal standards (Boltanski & Thévenot 2006) this contribution concentrates on formal standards that are written down in a document. In contrast to informal standards, which are comparable to common agreements and not reducible to formal rules as they are comprehensive and imply contextual knowledge, formal standards are more tangible and leave clear traces. Putting emphasis on standards' formalization and voluntariness we draw upon the recently proposed definition by organization scholars who specified a standard 'as a rule for common and voluntary use, decided by one or several people or organizations' (Brunsson et al. 2012: 616). By using the term 'standards' we thus refer to voluntary obligations that are often produced and implemented by organizations.

1.2 Prior research has drawn major attention to standards as a new and emergent means to fill governance voids and has argued that the demand for voluntary standards has notably emerged as a result of a waning confidence in governments and growing interdependency in globalized society (Büthe & Mattli 2010; Djelic & Sahlin-Andersson 2006; Ponte et al. 2011). Because the following of standards is a voluntary act, standardizers must argue and convince adopters as to why they should comply with their standards. The authority of standards is thereby usually derived from scientific knowledge and therefore expertise builds the main source for the elaboration and revision of voluntary standards (Loya & Boli 1999; Drori et al. 2003: 280-292; Jacobsson 2000). As a result, standardization is strongly intertwined with science and standards seem to provide rational and legitimate solutions for solving problems of coordination that cannot be addressed by legislation.

1.3 Taking into account that the reasons for standards' genesis are well elaborated and that standards constitute a highly rationalized form of coordination, we are interested in the consequences of the introduction of standards into a field where standards have not existed before. We aim to shed light on the variation of governance arrangements triggered by voluntary standardization and pursue the goal of illuminating evolutionary governance dynamics. Thereby we understand governance as as means of coordination that regulates the behaviour and decision-making of involved actors.

1.4 To study formal standards' effects on governance arrangements in a specific setting we apply an institutional approach that seems suitable for both a field-level analysis as well as research on issues of social coordination (Scott 1995). According to Brunsson (2000) voluntary standards need to be considered as a governance mode just as markets and hierarchical organizations are seen as modes of governance. All three forms of governance constitute institutions, which in their different ways guide the behaviour of actors. While markets and standardization are principally voluntary forms of governance, leaders of formal organizations can issue mandatory directives to their members and are usually held responsible for their organizations' actions. In contrast, it is difficult to hold standardizers responsible and in markets the sellers become only partly responsible. In line with these differences in the allocation of responsibility, formal organizations generate more complaints than markets and standards do. Furthermore, standardization is not regulated by extensive legislation, while markets and organizations are exenstively regulated by laws to facilitate their functioning. Furthermore, standards coordinate and control in a more indirect way than markets and formal organizations do, as they provide rules for the general case and cannot be used for deciding a particular case. Hence, the three institutions, which are all highly rationalized and generally well accepted, provide coordination and control differently and can therefore be discerned. The use of this analytical distinction will allow for an institutional analysis of standards' consquences on the governance of a field.

1.5 This research focuses on fair trade[2] in Switzerland as a paradigmatic case of succesful and voluntary standardization that promotes social justice beyond and across the boundaries of nation states (Winchester & Bailey 2012). Fair trade is commonly defined as follows:

Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. (FLO and WFTO 2009: 4)

1.6 To develop a comprehensive understanding of governance dynamics, the study includes the prehistory of formal fair trade standardization. This means as a first step we present empirical evidence about the field constitution before the introduction of formal standardization, which we can then use for comparison with the development in the aftermath of the launch of standards. Such a proceeding will enable us to explain how the introduction of formal standards has affected the coordination of fair trade. Due to this research interest we do not investigate governance in global value chains (Gibbon et al. 2008; Spencer 2009), but illuminate the impact of fair trade standards at field level, which seems to be generally undertheorized (Nicholls 2010).

1.7 We conducted an in-depth case study of the historical development of fair trade in Switzerland since the 1970s. In line with the overall rationality of standardization (Loya & Boli 1999), the trend in the history of the Swiss fair trade field can be subsumed under the notion of ongoing rationalization (Hudson et al. 2013: 29ff). While the concept of fair trade initially aimed at supporting producers in developing countries on the basis of an alternative trading system, it has gradually become a segment within the capitalist market system. This incorporation was based on the implementation of market-compatible standardization structures that caused significant growth in production and sales. Based on scientific methods of organizing – such as expert-based standards, audits, and third-party certification – a rational order has been set up. Contrary to what might be expected, this rationalization has not led to a simplification of governance arrangements. In contrast our case will exemplify how the introduction of standards has led to increased complexity and abstraction in the field.

1.8 The paper proceeds in the following fashion. In the next section, we introduce our case study approach and highlight peculiarities of the Swiss fair trade sector. Thereby we present our data set and the analysis of our data. The third section is dedicated to empirical findings about the historical development of the Swiss fair trade field with a focus on its institutional coordination. In the first part we present empirical evidence about the prehistory of fair trade standardization and elaborate on the origins and the creation of formal standards. The second part of the empirical section focuses on the consequences of standards' implementation and is structured by considered types of governance: organizations, markets and standards. Building on empirical findings, in section four we highlight the potential of standards to boost additional governing efforts. The use of standards as a means for creating differentiation instead of generating uniformity is thereby seen as a main reason for increased coordination demands. Taking into account the resulting interplay between distinct governance modes we present conceptual considerations that contribute to a better understanding of governance dynamics triggered by formal standardization. The paper concludes with a discussion about the contribution our study makes and two main suggestions for future research.

2.1 We employ a longitudinal case-study approach to empirically ground our understanding of voluntary standards' consequences on the coordination of a field. A case-study design does not only allow for detailed examination but also enables us to explain the origins and consequences of formal standards in a nuanced way (Yin 2009). As a level of analysis serves the organizational field, which was originally described as 'those organizations that, in the aggregate, constitute a recognized area of institutional life: key suppliers, resource and product consumers, regulatory agencies, and other organizations that produce similar services or products' (DiMaggio & Powell 1983: 143; cf. Fligstein & McAdam 2012), in our analysis, we investigate transformations in an organizational field that is formed around a specific issue (Hoffman 1999), namely fair trade in Switzerland. We investigate the historical development of this issue-based field and its organizational actors since the emergence of the first Swiss fair trade campaigns in the early 1970s. As a result, issues of fair trade consumption and individual consumer behaviour, which are often addressed under the notion of 'political consumerism' (Stolle & Micheletti 2013) go beyond the scope of this article. This does not mean that we call into question consumers' key role in the rise of fair trade, which has been demonstrated by several scholars (e.g. Brown 2013; Dubuisson-Quellier 2013).

2.2 The concept of fair trade aims at using trade as a means to support underprivileged producers in the developing countries and has developed into one of the most promising initiatives that promotes sustainable production and trade conditions (Huybrechts 2012). Fair trade organizations commit themselves to the following principles: market access for marginalized producers, sustainable and equitable relationships, capacity building and empowerment as well as consumer awareness raising and advocacy for wider reforms of international trade (FLO and WFTO 2009: 7-8). Fair trade in general is an early and typical phenomenon of private regulation (Abbott & Snidal 2013) and scientists highlight its pioneering role, as it formed part of the first wave of standardization dealing with sustainability (Djama et al. 2011). However, in the course of mainstreaming and the impressive growth of fair trade, critical voices have been raised problematizing its governance tools and questioning its impact as well as the maintenance of its original objectives (Dine et al. 2013). Despite this criticism fairly traded products enjoy great popularity in Switzerland. The institutional set up of Switzerland generally is characterized by high degrees of coordination (Passarge & Hasse 2013) and specifically, fair trade related peculiarities of this context include:

2.3 The focus on a national setting allows the historical development to be traced precisely and country-specific results are demanded for cross-country comparisons (Huybrechts & Reed 2010).[4] Furthermore it brings the opportunity to illustrate how the Swiss fair trade organizations became intertwined in a transnational network and how the field became increasingly coordinated at a distance through formal and abstract standardization mechanisms. However, the concentration on the Swiss setting entails a strong bias towards the northern hemisphere, which seems problematic if we are to seriously consider fair trade to be essentially about north–south trade relations. But taking into account the purpose of this paper, the exclusion of southern producers seems justifiable, because fair trade standards emerged and are revised in northern countries, and standards' impacts on producers' livelihoods are not of interest.[5]

2.4 Generally, data collection and data analysis were developed together in a rather iterative process. We gathered data in a problem-driven process from different sources:

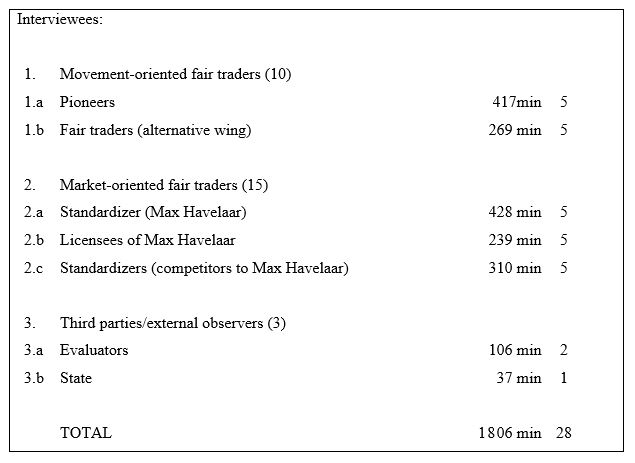

|

| Table 1. List of interviewees (source: own diagram) |

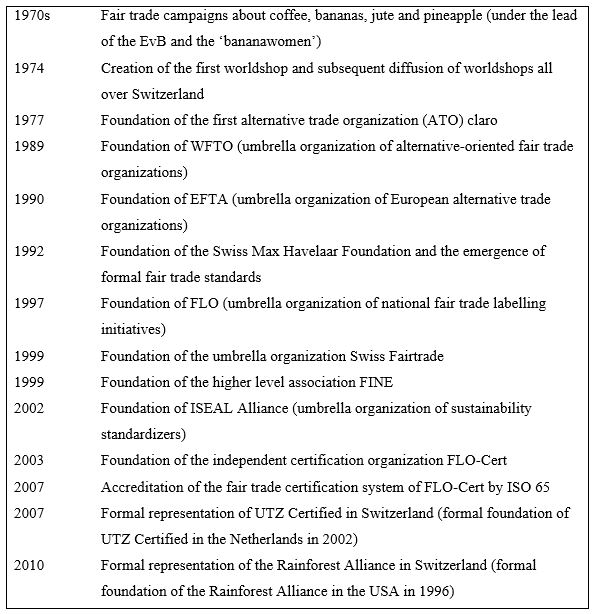

2.5 Through the triangulation of our set of data we first established a chronological account of the Swiss fair trade history (see table 2). Therefore we traced key events and established a time-ordered display that reconstructs the chronology of fair trade's development. To analyze our data and to highlight major trends with respect to issues of governance we employed the method of process-tracing, which allows an historical account to be converted into an analytical explanation on the basis of a theoretical orientation (George & Bennett 2005). Hence, the analysis of collected data is based upon an in-depth confrontation with theories on social coordination, which we sought to use in a creative way for theory development.

|

| Table 2. Overview of key events in the historical development of the Swiss fair trade field (source: own diagram) |

3.1 Field constitution before the introduction of formal standards: Pioneering fair trade organizations and an alternative niche market

Similar to the overall development of fair trade (Gendron et al. 2009) the Swiss fair trade movement came into existence in the 1970s when distinct nonprofit organizations started to campaign for more solidarity with the Third World. The campaigns arose from a broad Third World movement in Switzerland that claimed for a new Swiss development policy that would shift its focus from development aid to economic relationships and relations of explotation which thereby invoked broad debates about flight capital, the problem of famine or the question of debt burden (Kuhn 2011). In the context of unequal trading relationships from 1973 a courageous women's group started to conduct consumer campaigns in order to raise awareness about the poor working conditions of banana producers in Latin America.[6] In the same time period the nongovernmental organization Erklärung von Bern (EvB), with the support of like-minded organizations, started to conduct distinct consumer campaigns, one after another: first about coffee from Tanzania, later about jute from Bangladesh and even later about pineapples from the Philippines.[7] Due to the immediate success of their initial campaigns and to better organize the import of southern products, an alternative trade organization (ATO) called claro (at that time OS3) was founded in 1977 (Strahm 2008). During this time further ATOs came into existence, such as Gebana or Caritas Fairness, which was later taken over by claro (Krier 2005: 64; Martinelli 1998: 38).

3.2 The implementation of the consumer campaigns, the foundation of the ATOs and the impressive diffusion of worldshops all over Switzerland provided the starting point for the establishment of the first 'alternative food networks' (Goodman et al. 2012) in the country which were crucial for the emergence of a new trade paradigm (Webb 2007).[8] Interviewed experts agreed that the campaigning activities and early efforts of alternative trading of the 1970s and 1980s paved the way for the later succesful development of fair trade.[9] An informant explained for instance, that these pioneers 'raised the interest (for fair trade issues) beyond development organizations and church communities and therefore contributed (…) to the shaping of the field'.[10] However, fair trade was based upon the thrust at that time (Raynolds & Long 2007) and formal standards and sophisticated forms of audits did not yet exist. In this context, a fair trade activist acknowledged: 'standards, measurable standards, I have to say, were after my time'.[11]

3.3 In the early 1990s, when the prices for coffee on the world market had fallen, Swiss fair trade pioneers aimed at bringing fairly traded coffee to the shelves of Swiss supermarkets in order to achieve market growth and higher impact.[12] After having persuaded the powerful Swiss supermarket chains Coop and Migros, which have an impressive common market share of almost 80% (Krauskopf & Müller 2014), to sell fair trade coffee, six prestigious relief organizations founded the labelling initiative Max Havelaar, using the Dutch Max Havelaar initiative as a model.[13] The new Max Havelaar strategy that combined formal standards, certification and product labelling was promising for Swiss retailers as it allowed for product differentiation which made non-price competition possible. In other words, Max Havelaar offered conventional retailers, which were convinced that 'the basic principle of cheaper, cheaper, cheaper constitutes an aberration in food trade'[14] an opportunity to escape tough price wars. A certain degree of fair trade commitment by conventional retailers was crucial for the succesful launch of the fair trade standardization system. In this context an interviewee explained that the joint entrance of both retailers – Coop and Migros – into the fair trade market has been 'unpayable, since they allowed for public relation work and a distribution grid all over Switzerland'.[15] As a result, the prehistory of the fair trade standardization provides empirical evidence for Bartley's (2007) argument that the rise of sustainability standards needs both interested actors in the market – here, mainly the powerful supermarkets – and entrepreneurial actors of the field – here, the fair trade pioneering organizations.

3.4 Field constitution after the introduction of formal standards: Increasing governance efforts through the emergence of organizations, the development of a standards market and expanding standardization

Since its foundation, the standardizer Max Havelaar has achieved impressive growth through constant launches of new products[16] and licensing revenues have dramatically increased from a modest 303,421 Swiss francs in 1992 to 7,399,114 Swiss francs in 2013.[17] As a result, the standardizer became the dominant actor in the Swiss fair trade scene shortly after its foundation. An informant from the field described that 'out there exists the perception (…) that the Max Havelaar label is fair trade'.[18] Nonetheless, the pioneering fair trade organizations survived, maintained their alternative niche market and conducted occasional campaigning activities.[19] Consequently, the Swiss fair trade arena has now been characterized by different types of fair trade players which has led to a clash of movement- and market-oriented concepts of fair trade. A representative of the latter and member of the professional standardization organization depicted the resulting tensions in the following way: 'The whole world of the ATOs was based on ideology, idealism and trusting in solidarity, this is not intended to be pejorative, this was another spirit'.[20] Less emotionally, an interviewee explained that there were constant debates about 'whether the system needs to satisfy the market or whether the system needs to represent producers' interests at best'.[21] Against this background, new governance modes have shown up during its further development, as will now be outlined along ideal-typical types of institutional coordination: first hierarchical organizations, then markets and finally standards.

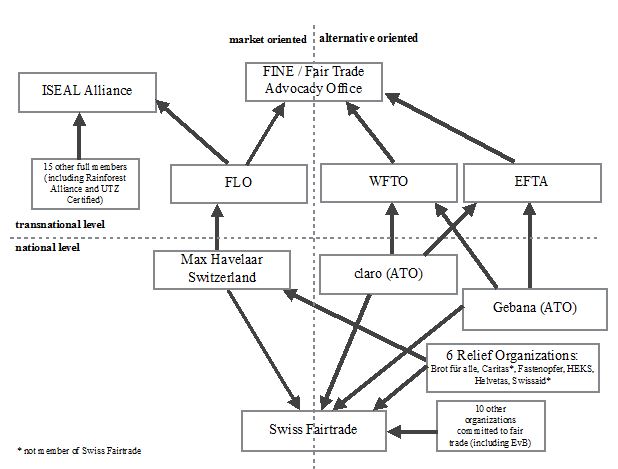

3.5 Emergence of hierarchical organizations: Regarding coordination through hierarchical organizations, our data shows that in succession to the development of voluntary standards new organizations were either founded to harmonize the conflictual fair trade field or to professionalize and legitimize the fair trade standardization system. Hence, the above-mentioned dilemma between distinct fair trade players, caused by the launch of formal standards, triggered the emergence of new organizations. Swiss fair traders from both wings started to come together in the mid 1990s and created a formal umbrella association called Swiss Fairtrade (at that time Schweizer Forum Fairer Handel) in 1999 to intensify their cooperation and to consolidate their power (Schaber & van Dok 2008). Also, on the transnational level, new umbrella associations with Swiss membership strove for better coordination among differently oriented fair trade players (see table 3). In 1997 the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation, together with other national labelling initiatives, created the umbrella organization Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO) to formalize their cooperation and to harmonize their efforts.[22] Earlier, the more grass-roots-oriented wing had already established its own higher level associations: in 1987 they founded the European Fair Trade Association (EFTA), which unites large alternative trade organizations, and two years later they created the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO), which brings together numerous fair trade organizations (Kocken 2006). In 1999 the Network of European World Shops (News!)[23] and the above-mentioned associations once again formed an umbrella organization called FINE to push coordination and reduce the potential for conflict among distinct ideological fair trade concepts (Hauff & Claus 2012).[24] FINE ceased to exist in its original form and transformed into an advocacy office in Brussels in 2004 where it now aims to influence Europen policymakers (Cremona & Duran 2013a). Overall, several organizations were founded, with the aim of reducing the conflictual dilemma between commercial-oriented concepts and more movement-oriented ideas of fair trade through hierarchical forms of coordination.

|

| Table 3. Membership relations of fair trade organizations with a focus on Swiss players (source: own diagram) |

3.6 Apart from the creation of organizations that aim at harmonizing the conflictual fair trade field hierarchically, we discover the emergence of two organizations that pursue the goal of governing and legitimizing the fair trade standardization system. At the beginning, employees of the fair trade labelling organizations, such as Max Havelaar in Switzerland, were responsible for the monitoring of the standards' implementation until they realized, that 'you cannot (…) set the rules, doing the consulting, conducting the controlling and then say, everything is in order'.[25] In other words, as the market for certified fair trade products expanded, the need for credible certification became inevitable and the certification company FLO-Cert was founded in 2003 (FLO-Cert 2013). Independent third-party certification is nowadays widely used and implies the involvement of additional organizations in the coordination of the standardization (Loconto & Busch 2010). But the involvment of FLO-Cert has led to the question of whether their auditing practices are really reliable. To demonstrate its competence as a certification body FLO-Cert has therefore been accredited with the ISO 65 norm since 2007 (FLO-Cert 2013). This means FLO-Cert is now monitored by another independent third party to make sure that it complies to a set of standards that regulates how to monitor the implementation of standards. With regard to such audit spirals an expert critically noted: 'This has nothing more to do with fair trade. It is only about processes'.[26]

3.7 Development of a standards market: With respect to governance through markets, we identify that in the wake of fair trade's success, new standardizers entered the field and built the starting point of the establishment of a standards market. This means, alternative options to the well-established fair trade standardization system of Max Havelaar have arisen that likewise provide rational labelling systems to signal the ethical superiority of southern products.[27] According to several interview partners the sustainability initiatives Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified need to be seen as severe competitors of the standardization system of Max Havelaar in the Swiss setting.[28] Using the same instruments as Max Havelaar these initiatives offer a sustainability label to conventional market participants and guarantee that the production and trade of southern commodities comply to certain sustainability criteria. As a result, conventional firms that share an interest in the purchase of fairly traded products can now choose between different sustainability standards that put comparable services on offer.[29]

3.8 The plurality of offered sustainability standards for southern products has resulted in the emergence of a market for standards. In accordance with other findings about the creation of standards markets (Ponte & Riisgaard 2011; Reinecke et al. 2012), our historical account indicates that in addition to the early fair trade product market, a new and supplementary market for sustainability standards came into existence. The coexistence of comparable but slighty different standardization systems poses new challenges. Due to standards causing confusion a multitude evaluation systems have emerged that 'target to provide independent information to consumers and experts (…) by fighting their way through the label jungle'[30] as explained by an external observer of the field.[31] But the diversity of standards also affects the southern producers, this is why a state representative pleaded for 'a harmonization of these labels, in terms of the mutual recognition of audits and certifications (…) in order to reduce the transaction costs for producers'.[32] Beyond, critical voices emphasize that dense competition of standard setters in the field might bring about business-friendly adaptations and a lowering of existing standards (e.g. Jaffee & Howard 2010; Raynolds et al. 2007). By contrast, others argue that competition does not lead to a 'race to the bottom' in the standards (Ponte & Riisgaard 2011). While it seems questionable how competition among standardizers affects the content of standards, it seems clear that the appearance of a formal standardization system and the subsequent emergence of rivaling standardizers have caused more market structures in the field.

3.9 Expansion of standardization: Concerning governance through standards, our findings indicate that subsequent to fair trade's formal standardization, additional standard frameworks were elaborated as means for organizing. Hence, the evolution of the Swiss fair trade field does not only demonstrate trends towards more organizations and dense competition among standardizers, it also hints at the multiplication of standards and a tendency towards a standardization of standards. We find two types of standards' expansion: on the one hand there are the new standardization frameworks that are either complementary to or competing with existing standards, and on the other there are the meta-standards that define rules about how to accurately set, revise and monitor voluntary rules.

3.10 It seems trivial to note that the emergence of new competitors – UTZ Certified and Rainforest Alliance – has led to the appearance of new standard documents. More intriguing is the fact that the alternative-oriented fair trade organizations that were brought together by the WFTO decided to develop their own certification standards for their members in 2011 (WFTO 2014). Because this system focuses on the certification of organizations, which stands in sharp contrast to the product-certification route by FLO, the two standardization sytems need to be seen as complementary components of fair trade (Cremona & Duran 2013b). Astonishingly, even the Swiss umbrella association, Swiss Fairtrade, presents its own standardization system for their members by building upon the standards of FLO and WFTO (Swiss Fairtrade 2008). Hence, since the succesful voluntary standardization of fair trade through Max Havelaar in the 1990s, we detect the rise of additional standards that either harmoniously supplement existing standards or pose a threat to them. Irrespective of the nature of their relationships, all of these rule systems need to be considered as further governance efforts in the fair trade field.

3.11 Beyond complementary and competing standards our case hints at the rise of meta-standards that can simply be understood as standards about standards. So we report on a standard framework that no longer has the southern commodities as objects of standardization but the standardization itself. The foundation of the International Social and Environmental Accreditation and Labelling Alliance (ISEAL), which has brought together sustainability standardizers (including FLO, Rainforest Alliance, UTZ Certified) and promoted best practice of sustainability standardization since 2002, is an attempt to govern sustainability standardization systems through meta-standards. The ISEAL sets standards for their members 'defining a range of procedures, which are meant to assure both the conditions for standards to promote sustainability and for harmonization among standards to take place' (Djama et al. 2011: 201f.). These meta-standards that aim at orchestrating existing standard-setting practices are an outcome of formal standardization and the emerging standards' plurality.

4.1 Our institutional analysis indicates that the implementation of voluntary standards has led to complex governance structures in the fair trade field. While the concentration on legitimate standardization practices is generally perceived to be controversial, as it bears the risk of overriding the original purpose of fair north-south trading relations instead of serving it (Renard & Loconto 2013), our contribution seeks to highlight, that ideal-typical forms of social order have intensified since the introduction of voluntary standards:

4.2 While aiming to reduce the complexity in the fair trade field, these rational governance efforts paradoxically have contributed an augmentation of distinct and intermingling coordination modes and we detect an intertwinement of ideal types of social coordination. Thereby the field has become increasingly organized at a distance through abstract forms of governance. This means distinct types of institutional coordination have arisen in the aftermath of fair trade's formal standardization and pushed field governance to higher levels of abstraction and complexity. Thus, it can be argued that the introduction of standards has not replaced traditional forms of coordination, but rather, it has resulted in a dynamic interplay between governance modes.

4.3 Claiming that standards do not necessarily threaten established modes of governance but rather have the potential to boost them leads us to conclude that voluntary standards might create new governance demands. But why do rational standards that are generally perceived as a new and rational form of coordination provoke escalating governance structures? A look into the history of standardization shows that standards were originally located in the technical domain, where they were used to achieve compatability and interoperability (Loya and Boli 1999) and they have only recently gained popularity in social domains (Drori et al. 2003: 280–292). In the course of this expansion, rational standards have no longer been used solely for the generation of technical uniformity but rather have come to be utilized to make a difference and to signal certain quality features of products and services, such as pesticide-free, animal-friendly, CO2-free or simply eco-friendly. Hence standardization is now also utilized to create differentiation (Busch 2011: 151–200). Fair trade is such a standard framework that allows fairly traded commodities to be distinguished from others and therefore poses a typical form of standardized differentiation.

4.4 When standards are used as an instrument of differentiation they might call for supplementary governance efforts that result in an enhancement of institutional coordination, as demonstrated in our case. Here, the use of voluntary standards has not only enabled the marking of a moral difference to conventionally traded products but also caused a distinction between the alternative fair trade organizations on the one hand and the market-oriented fair trade standardizer with its conventional partners on the other. The resulting tensions were supposed to be harmonized through the foundation of hierarchical organizations that bring the distinct wings of fair trade together. Moreover, new organizations have emerged to better organize the growing fair trade standardization system itself. Legitimation endeavours made it necessary to involve an independent certification body and an accreditation organization to credibly claim that the standardized products are of superior quality. Making the system competitive and more legitimate seems important, since the fair trade standardization system of Max Havelaar has been confronted with new competitors – Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified – whose labels also account for sustainability issues on the basis of formal standards. The plurality of these initiatives mainly builds upon the principle of standardized differentation that facilitates the coexistence of similar but slightly distinct standards. Market structures and new forms of standardization have arisen to bring order to the multiplicity of these sustainability initiatives. Our case study thus reveals an enforcement of distinct governance modes triggered by voluntary standardization that does not target uniformity but highlights moral differences.

4.5 In our reading, scholars accord little attention to the issue of the mutual interplay of distinct forms governance that we detect in our case research. In emphasizing the interrelation of distinct forms of governance, it seems that a framework is required that addresses the co-evolution of distinct forms of governance instead of simply comparing them. Such an ecological perspective, which focuses on the interplay of governance modes and which emphasizes mutual dependencies between them, stands in sharp contrast to the widespread comparative lens. This lens conceptualizes analytically distinct forms of governance as alternatives that can be selected by decision makers and for which it is assumed that the fittest outperforms its less competitive rivals. The basic idea of analytically distinguishing between competing types of governance dates back to the 1930s when Ronald Coase (1937) raised the question regarding why contemporary capitalism is composed of so many large organizations that restrict market mechanisms. Following Coase's (1937) perspective, Oliver Williamson (1975) systematically compared market- and organization-based transactions. According to Williamson (1975), both types of transaction imply costs that vary with respect to asset specificities and context variables, such as regulation and available technologies. The boundaries of a firm, then, indicate which transaction problems are dealt with most efficiently by hierarchies and which ones are less costly when based on market principles.

4.6 Williamson described markets and hierarchies as (the only) ideal types of coordination. This analytical concept has stimulated a broad range of critical responses in organization research and economic sociology (cf. Hasse 2015). An influential argument against Williamson was developed by Walter Powell (1990) who identified networks as a mode of coordination that is distinct from both markets and hierarchies. As the discussion of network-based forms of economic organization continued, it became evident that there was a large variety of networks (Hage & Alter 1997). Nonetheless, the analytical distinction between markets, hierarchies and networks has become common ground in research on governance, particularly in organization research, institutional economics, economic sociology, the political sciences and in research on innovation systems.[33] In line with such comparative perspectives, further research has elaborated on the differences between distinct modes of governance, conceptualizing associations (Streeck & Schmitter 1985), community (Adler 2001) or bazaar governance (Demil & Lecocq 2006) as further types of coordination which can be distinguished from markets and hierarchies. The basic idea is that different modes of governance can be utilized in order to fulfil requirements of coordination. The analysis of Brunsson (2000), which we used as a theoretical orientation, is in line with such thinking. It implies a comparative lens which emphasizes similarities and differences between standardization, hierarchical organizations and markets.

4.7 Our longitudinal case study analysis of the Swiss fair trade sector supports the assumption that voluntary standards have become a significant institution in the coordination of modern society. It has profoundly benefited from the analytical distinction between types of governance: markets, organizations and standards. However, the case does not suggest that one should conceptualize governance modes as alternatives that simply compete with each other and which can be chosen on the basis of either/or decisions because in the fair trade field the introduction of formal standardization systems resulted in a strengthening of governance efforts; the case, instead, points at dynamic interplays and interdependencies in the long run. As a consequence we emphasize that standards, regardless of the extent to which they compete with other modes of governance, can – and have – become objects of coordination via markets, hierarchical organizations and (meta-)standards.

5.1 Using an institutional approach we have investigated the historical development of the Swiss fair trade field since its emergence and examined the consequences of voluntary standardization on its governance arrangements. Thereby we found a constant enhancement of governance modes since the introduction of formal fair trade standards in the early 1990s. This means voluntary standardization has led to intensifying governance efforts through more organizations, more markets, and more standards. Hence, voluntary standardization has not only given rise to a tendency towards more standards (Epstein 2009; Botzem & Quack 2006) but also to an increase of more classic governance efforts, namely hierarchical organizations and markets. In contrast to compatibility standards that typically aim at creating uniformity and interoperability, fair trade standards constitute a form of standardized differentiation and therefore target the accentuation of differences. This peculiarity has been identified as a major source for the rise of supplementary governance efforts caused by voluntary sustainability standardization.

5.2 Generalizing from our case, we argue that voluntary standards as a particular mode of governance does not act as a functional equivalent to other forms of institutional coordination but rather leads to their complex interplay. Consequently, our study provides evidence that ideal types of coordination are intertwined and combined in the empirical world (Bradach & Eccles 1989). In the past, seminal literature on social coordination has created the impression that distinct forms of governance are substitutes for each other that can be deliberately chosen. In the aftermath of Williamson's (1975) dichotomous view of markets and hierarchies, Streeck and Schmitter (1985) contended that associations provide a further basis for social order in advanced industrial societies and Powell (1990) argued that networks forms constitute a distinct mode of coordination. Similarly and most important in the realm of this research, Brunsson (2000) stated that standards have developed into a fundamental and discrete type of social order. In contrast to this line of work, which places emphasis on distinctions between governance modes that possibly undermine each other, our study brings forward interdependencies between alternative means for organizing and argues that governance modes can enhance one another. This means the upsurge and dominance of a particular form of governance does not have to go along with a weakening of other coordination modes but rather has the potential to strenghten and boost them. While it has been shown that competition can strengthen organizations against the expectations of internal and external stakeholders (Hasse & Krücken 2013), our empirical research findings demonstrate that standards can result in founding new organizations and associations, forming markets and introducing new standards. Taking into account the mutually reinforcing relationship between governance modes leads us to conclude that the evolution of governance arrangements needs to be seen as a historically contingent, ongoing and ever dynamic interplay between ideal-typical forms of coordination.

5.3 In light of our findings, we identify two research perspectives. Firstly, we need to better elucidate the concurrence of voluntary standards with other modes of governance by applying an ecological perspective, as proposed in this article. This means sociological research on questions of coordination should draw attention to the mutual interplay of distinct forms of governance, instead of limiting its focus on their contrasts. Specifically, the formation and development of markets for standards needs further examination. So far, economists have particularly emphasized that the use of standards results in increased market efficiency and the reduction of transaction costs (Hawkins et al. 1995; Katz & Shapiro 1985). In contrast, our findings show that standards and their proliferation might lead to new governance efforts and the emergence of a standards market. Future research thus needs to address the coordination of plural standards, including their underlying standardizers. The ordering of sustainability standards thereby seems to be a pressing subject of investigation, taking into account that the Ecolabel Index (2014) currently tracks 458 ecolabels. How these standardization frameworks will and can be coordinated to allow for transparency and comparability is not only of interest to sociologists and scholars in governance but also practitioners. Secondly, what does it mean when formal standardization leads to the rise of new and cumulative standards? Does this escalation of rules mean that we head towards neoliberal bureaucratization, as proposed by Hibou (2012)? This self-enforcing trend of governing through standards not only raises questions regarding the old topic of bureaucratization, but the sorting out of the standards' chaos also seems highly relevant for standard adopters and consumers who are increasingly confronted with a bewildering amount of standards options.

1This contribution forms part of a larger research project entitled 'Organization and Rationalization of Fair Trade' which is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

2Practitioners usually distinguish between fair trade (written as two words) to refer to an organized social movement which aims at supporting southern and marginalized producers by raising consumer awareness with market-based strategies, and fairtrade (written as one word) to denote the product certification operated by FLO (WFTO et al. 2011). To enhance the legibility of this paper, we constantly use the term 'fair trade'.

3Source: annual report Max Havelaar 2013.

4Interestingly, despite its leading role, fair trade in Switzerland has not attracted systematic attention from social scientists. For an exception see the study of Mahé (2010) on certified fair trade bananas in Switzerland.

5The supremacy of northern countries and the resulting one-sidedness of the fair trade standardizing procedure was subjected to downsizing through the formal integration of producer networks' representatives in the standard-setting process. (Fairtrade International 2012). However, the headquarters where the standardization takes place is still localized in the north and debates on good standardization practices are very much a phenomenon of northern countries.

6For an historical account of the campaigning activities and a rich description of the history of the so-called 'bananawomen' see the biographical study of the leader of the women's group, Brunner (1999).

7For an historical account of the campaigns of the EvB see the biographical studies of Holenstein and colleagues (2008).

8The first Swiss worldshop came into existence in Uster in 1974 and due to their impressive expansion they rapidly reached the number of 300. Source: interviews with fair trade pioneers in May and November 2013.

9Source: interviews with fair trade pioneers in February, May, October and November 2013; interviews with members of the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation in May 2012 and February 2013; interviews with members of alternative fair trade organizaions in May 2013 and January 2014; interviews with members of conventional retail in October 2013 and December 2013.

10Source: interview with a fair trade pioneer in October 2013.

11Source: interview with a Swiss fair trade pioneer in November 2013.

12To commercialize fairly traded products, Swiss relief organizations (Swissaid, Fastenopfer, Brot für Brüder, Helvetas) commissioned a feasibility study in 1991. Source: interview with a former member of the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation in February 2013.

13Founding members of the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation were Brot für alle, Caritias Schweiz, Fastenopfer, HEKS, Helvetas, Swissaid. Source: Max Havelaar annual report 1992.

14Source: interview with a member of a Swiss supermarket chain in October 2013.

15Source: interview with a member of an alternative fair trade organization in May 2013.

16Some of the most important product launches include: honey (1993), cocoa (1994), tea (1995), bananas (1997), orange juice (1999), cut flowers (2001), cotton (2005). Source: Max Havelaar annual reports since 1992.

17Source: Max Havelaar annual report 1992 and 2013.

18Source: interview with a member of an alternative fair trade organization in April 2013.

19The fair trade campaigns about cut flowers, which were conducted under the lead of the Swiss nonprofit organization Arbeitsgruppe Schweiz Kolumbien (ask) met with considerable public interest. Source: interview with a fair trade activist in October 2013.

20Source: interview with a former member of the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation in February 2013.

21Source: interview with a former member of the foundation board of the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation in October 2011.

22Source: Max Havelaar annual report 1996.

23News! existed from 1994 until 2008 and was aimed at coordinating national worldshop associations. Since its dissolution, the working activitivies of News! have been integrated into the WFTO. Source: WFTO annual report 2008.

24For their cooperation, the four fair trade umbrella organizations (FLO, IFAT now WFTO, News!, EFTA) created the acronym FINE, by which each letter corresponds to one organization.

25Source: interview with a former member of the Swiss Max Havelaar Foundation in February 2013.

26 Source: interview with a member of the Max Havelaar Foundation in October 2011.

27UTZ Certified was founded in 2002 and UTZ Certified products were sold for the first time in Switzerland in 2007. Rainforest Alliance was founded in 1996 and has been formally represented in Switzerland since 2010.

28Source: interviews with members of the Max Havelaar Foundation and FLO in October and December 2011, February 2013; interviews with members of sustainability standardizers in December 2012 and March 2013; interviews with members of conventional retail in September, November and December 2013.

29The study of Raynolds et al. (2007) provides detailed information about the differences between these standardization systems.

30Source: interview with a member of an evaluation organization in October 2011.

31Evaluations of standardization systems are provided by the Swiss nongovernmental organizations WWF (World Wildlife Fund 2009) and Pusch (Praktischer Umweltschutz Schweiz)

32Source: interview with a member of a Swiss state secretariat in February 2012.

33Comparative institutional analysis with its primary confrontation of liberal and coordinated economies is also devoted to this line of thinking (cf. Morgan et al. 2010). Whereas liberal economies are described as being based on market principles and powerful large firms (hierarchies), coordinated economies seem to put more weight on network-based forms of coordination – i.e. governance by powerful associations or even cartels and many informal inter-firm relations – and on regulation by the state.

ABBOTT, KW and Snidal, D (2013) Taking responsive regulation transnational: Strategies for international organizations. Regulation & Governance, Vol. 7, No.1, p. 95-113.

ADLER, P S (2001) Market, hierarchy, and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism. Organization Science, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 215-234.

BARTLEY, T (2007) Institutional emergence in an era of globalization: The rise of transnational private regulation of labor and environmental conditions. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 113, No. 2, p. 297-351.

BOLTANSKI, L and Thévenot, L (2006) On Justification: Economies of Worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

BOTZEM, S and Quack, S (2006) Contested rules and shifting boundaries: International standard-setting in accounting in Djelic, M L and Sahlin-Andersson, K (Eds.) Transnational Governance: Institutional Dynamics of Regulation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

BRADACH, J L and Eccles, R G (1989) Price, authority, and trust: From ideal types to plural forms. Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 15, p. 97-118.

BROWN, K R (2013) Buying into Fair Trade: Culture, Morality, and Consumption. New York and London: New York University Press.

BRUNNER, U (1999) Bananenfrauen. Frauenfeld: Huber + Company Ag.

BRUNSSON, N (2000) Organizations, markets and standardization in Brunsson, N and Jacobsson, B (Eds.) A World of Standards, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

BRUNSSON, N and Jacobsson B (2000) A World of Standards. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

BRUNSSON N, Rasche, A and Seidl, D (2012) The dynamics of standardization: Three perspectives on standards in organization studies. Organization Studies, Vol. 33, No. 5-6, p. 613-632.

BUSCH, L (2011) Standards: Recipes for Reality. Cambridge, Massachussettes: MIT Press.

BÜTHE, T and Mattli, W (2010) International standards and standard-setting bodies in Coen, D, Graham, W and Grant, W (Eds.) Oxford Handbook on Business and Government, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

COASE, R H (1937) The nature of the firm. Economica, Vol. 4, No. 16, p. 386-405.

CREMONA, M and Duran, G M (2013a) Fair trade in the European Union. Regulatory and institutional aspects in Granville, B and Dine, J (Eds.) The Processes and Practices of Fair Trade: Trust, Ethics and Governance, Oxford; New York: Routledge.

CREMONA, M and Duran, G M (2013b) The international fair trade movement in Granville, B and Dine, J (Eds.) The Processes and Practices of Fair Trade: Trust, Ethics and Governance, Oxford; New York: Routledge.

DEMIL, B and Lecocq, X (2006) Neither market nor hierarchy nor network: The emergence of bazaar governance. Organization Studies, Vol. 27, No. 10, p. 1447-1466.

DIMAGGIO, P J and Powell, W W (1983) The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, p. 147-160.

DINE, J, Granville, B and Telfrod, S (2013a) Overview and introduction in Granville, B and Dine, J (Eds.) The Processes and Practices of Fair Trade: Trust, Ethics and Governance, Oxford; New York: Routledge.

DJAMA, M, Fouilleux, E and Vagneron, I (2011) Standard-setting, certifying, benchmarking: A governmentality approach to sustainability standards in the agro-food sector in Ponte, S, Gibbon, P and Vestergaard, J (Eds.) Governing through Standards: Origins, Drivers and Limitations. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

DJELIC, M L and Sahlin-Andersson, K (2006) Transnational Governance: Institutional Dynamics of Regulation. Cambridge: University Press.

DRORI, G S, Ramirez, F O and Schofer, E (2003) Science in the Modern World Polity: Institutionalization and Globalization. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

DUBUISSON-QUELLIER, S (2013) Ethical Consumption. Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.

ECOLABEL INDEX (2014) Ecolabel Index – All Ecolabels. Downloaded from: http://www.ecolabelindex.com/ accessed 10/09/14.

EPSTEIN, S (2009) Beyond the standard human? in Lampland, M and Star, S L (Eds.) Standards and their Stories: How Quantifying, Classifying, and Formalizing Practices Shape Everyday Life, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

FAIR TRADE INSTITUTE (2014) Collection. Downloaded from: http://www.fairtrade-institute.org/db/publications/index accessed 22/09/14.

FAIRTRADE International (2012) Standard Operating Procedure Development of Fairtrade Standards. Downloaded from: http://www.fairtrade.net/setting-the-standards.html accessed 05/10/14.

FLIGSTEIN, N and McAdam, D (2012) A Theory of Fields. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

FLO-CERT (2013) Quality Manual. Explanatory Document. Downloaded from: http://www.flo-cert.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/QM-QualityManual-ED-55.pdf. accessed 23/11/14.

FLO AND WFTO (2009) A Charter of Fair Trade Principles. Downloaded from < http://www.fairtrade.net/what-is-fairtrade.html. accessed 09/03/14.

GENDRON, C, Bisaillon, V and Rance, A I O (2009) The institutionalization of fair trade: More than just a degraded form of social action. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 86, No. 1, p. 63-79.

GEORGE, A L and Bennett, A (2005) Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

GIBBON, P, Bair, J and Ponte, S (2008) Governing global value chains: An introduction. Economy and Society, Vol. 37, No. 3, p. 315-338.

GLÄSER, J and Laudel, G (2010) Experteninterviews und Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse (4th ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

GLOBESCAN (2011) Shopping Choices can Make a Positive Difference to Farmers and Workers in Developing Countries: Global Poll. Downloaded from: < http://www.globescan.com/commentary-and-analysis/press-releases/press-releases-2011/94-press-releases-2011/145-high-trust-and-global-recognition-makes-fairtrade-an-enabler-of-ethical-consumer-choice.html> accessed 01/04/13.

GOODMAN, D, Dupuis, M E, DuPuis, E M and Goodman, M K (2012) Alternative Food Networks: Knowledge, Practice, and Politics. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

HAGE, J and Alter, C (1997) A typology of interorganizational relations and networks in Hollingsworth, J R and Boyer, R (Eds.) Contemporary Capitalism: The Embeddedness of Institutions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

HASSE, R (2015) Organisationsforschung - und Wettbewerb in Apelt, M and Willkesmann, U (Eds.) Zur Zukunft der Organisationssoziologie. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

HASSE, R and Krücken, G (2013) Competition and Actorhood. A futher Expansion of the Institutional Agenda. Sociologia Internationalis Vol. 51, p.181-205.

HAUFF, M and Claus, M (2012) Fair Trade. Ein Konzept nachhaltigen Handels. Stuttgart: UTB.

HAWKINS, R W, Mansell, R E and Skea, J (1995) Standards, Innovation and Competitiveness: The Politics and Economics of Standards in Natural and Technical Environments. Aldershot: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

HIBOU, B (2012) La Bureaucratisation du Monde à l'Ere Néolibérale. Paris: La Découverte.

HIGGINS, V and Larner, W (2010) Calculating the Social: Standards and the Reconfiguration of Governing. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

HOFFMAN, A J (1999) Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the U.S. chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 42, No. 4, p. 351-371.

HOLENSTEIN, A M, Renschler, R and Strahm, R (2008) Entwicklung heisst Befreiung: Erinnerungen an die Pionierzeit der Erklärung von Bern (1968–1985). Zürich: Chronos Verlag.

HUDSON, I, Hudson, M and Fridell, M (2013) Fair Trade, Sustainability and Social Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

HUYBRECHTS, B and Reed, D (2010) Introduction: Fair trade in different national contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 92, No. 2, p. 147-150.

HUYBRECHTS, B (2012) Fair Trade Organizations and Social Enterprise. Social Innovation through Hybrid Organization Models. New York: Routledge.

JACOBSSON, B (2000) Standardization and expert knowledge in Brunsson, N and Jacobsson, B (Eds.) A World of Standards, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

JAFFEE, D and Howard, P H (2010) Corporate cooptation of organic and fair trade standards. Agriculture and Human Values, Vol. 27, No. 4, p. 387-399.

KATZ, M L and Shapiro, C (1985) Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. The American Economic Review, Vol. 75, No. 3, p. 424-440.

KOCKEN, M (2006) Sixty Years of Fair Trade. A Brief History of the Fair Trade Movement. Downloaded from: http://www.european-fair-trade-association.org/efta/Doc/History.pdf accessed 02/03/14.

KRAUSKOPF, P L and Müller, C (2014) Wettbewerbssituation im Detailhandel. Downloaded from: http://project.zhaw.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/W/ateliers/X8_Atelier/Gutachten_Wettbewerbssituation_im_Detailhandel.pdf accessed 09/09/14.

KRIER, J M (2005) Fair Trade in Europe 2005. Facts and Figures on Fair Trade in 25 European Countries. Brussels: Fair Trade Advocacy Office. Downloaded from: http://www.european-fair-trade-association.org/efta/Doc/FT-E-2007.pdf accessed 25/03/14.

KUHN, K (2005) Fairer Handel und Kalter Krieg: Selbstwahrnehmung und Positionierung der Fair-Trade-Bewegung in der Schweiz, 1973–1990. Edition Soziothek.

KUHN, K (2011) Entwicklungspolitische Solidarität: die Dritte-Welt-Bewegung in der Schweiz zwischen Kritik und Politik (1975–1992). Zürich: Chronos Verlag.

LAMPLAND, M and Star, S L (2009) Standards and their Stories: How Quantifying, Classifying, and Formalizing Practices Shape Everyday Life. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

LOCONTO, A and Busch, L (2010) Standards, techno-economic networks, and playing fields: Performing the global market economy. Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 17, No. 3, p. 507-536.

LOYA, T A and Boli, J (1999) Standardization in the world polity: Technical rationality over power in Boli, J and Thomas, G M (Eds.) Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations since 1875, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

MAHÉ, T (2010) Are stated preferences confirmed by purchasing behaviours? The case of fair trade-certified bananas in Switzerland. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 92, No. 2, p. 301-315.

MARTINELLI, E (1998) EFTA Survey on Fair Trade in Europe. Facts and Figures on the Fair Trade Sector in 16 European Countries. Downloaded from: http://www.european-fair-trade-association.org/efta/Doc/FT-E-1998.pdf> accessed 17/11/2014.

MORGAN, G, Campbell, J, Crouch, C, Pedersen, O K and Whitley, R (2010) The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Institutional Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

NICHOLLS, A (2010) Fair trade: Towards an economics of virtue. Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 92, p. 241-255.

OEKOM RESARCH (2011) Presseinformation. Schweizer Einzelhändler beim Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement führend. Downloaded from: http://www.oekom-research.com/homepage/german/oekom_research_Einzelhandel_09062011.pdf accessed 01/05/14.

PASSARGE, E and Hasse, R (2013) Risikokapital in der Schweiz – eine institutionelle Analyse. Swiss Journal of Sociology, Vol. 39, p. 465-491.

PONTE, S, Gibbon, P and Vestergaard, J (2011) Governing through Standards: Origins, Drivers and Limitations. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

PONTE, S and Riisgaard, L (2011) Competition, 'best practices' and exclusion in the market for social and environmental standards in Ponte, S, Gibbon, P and Vestergaard, J (Eds.) Governing through Standards: Origins, Drivers and Limitations, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

POWELL, W W (1990) Neither market nor hierarchy: Network forms of organization. Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 12, p. 295-336.

RAYNOLDS, L T and Long, M A (2007) Fair/alternative trade: Historical and empirical dimensions in Raynolds, L T, Murray, D L and Wilkinson, J (Eds.) Fair Trade: The Challenges of Transforming Globalization, London and New York: Routledge.

RAYNOLDS, L T, Murray, D L and Heller, A (2007) Regulating sustainability in the coffee sector: A comparative analysis of third-party environmental and social certification initiatives. Agriculture and Human Values, Vol. 24, No. 2, p. 147-163.

REINECKE, J, Manning, S and vonHagen, O (2012) The emergence of a standards market: Multiplicity of sustainability standards in the global coffee industry. Organization Studies, Vol. 33, No. 5-6, p. 791-814.

RENARD, L and Loconto, B (2013) Competing Logics in the Further Standardization of Fair Trade: ISEAL and the Simbolo de Pequenos Productores. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, Vol. 20, No. 1, p. 51-68.

SCHABER, C and van Dok, G (2008) Die Zukunft des Fairen Handels. Luzern: Caritas-Verlag.

SCOTT, W R (1995) Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

SPENCER, D (2009) Governing through standards: Networks, failure and auditing. Sociological Research Online, Vol. 15, Issue 4: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/15/4/6.html.

STOLLE, D and Micheletti, M (2013) Political Consumerism: Global Responsibility in Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

STRAHM, R (2008) Der aktionserprobte Achtundsechziger im Team der EvB 1974–1978 in Holenstein, A M, Renschler, R, Strahm, R (Eds.) Entwicklung heisst Befreiung: Erinnerungen an die Pionierzeit der Erklärung von Bern (1968–1985), Zürick: Chronos Verlag.

STREECK, W and Schmitter, P C (1985) Community, market, state – and associations? The prospective contribution of interest governance to social order. European Sociological Review, Vol. 1, No. 2, p. 119-138.

SWISS FAIRTRADE (2008) Swiss Fairtrade. Grundsätze und Standards. Downloaded from: http://www.swissfairtrade.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/swissfairtrade/Grundlagen/SWISS_FAIRTRADE_Standards_V1.3_d.pdf accessed 12/11/13.

TIMMERMANS, S and Epstein, S (2010) A world of standards but not a standard world: Toward a sociology of standards and standardization. Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 36, No. 1, p. 69-89.

WEBB, J (2007) Seduced or sceptical consumers? Organised action and the case of fair trade coffee. Sociological Research Online, Vol. 12, Issue 3: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/3/5.html.

WFTO (2014) WFTO Guarantee System Handbook. Introduction. Downloaded from: http://www.wfto.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=2005&Itemid=1 accessed 08/07/14.

WFTO, FLO, FLO-Cert (2011) Fair Trade Glossary. Downloaded from: http://www.fairtrade.net/what-is-fairtrade.html accessed 03/11/14.

WILLIAMSON, O (1975) Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: Free Press.

WINCHESTER, N and Bailey, N (2012) Making sense of "global" social justice: Claims for justice in a global labour market. Sociological Research Online, Vol. 17, Issue 4: http://www.socresonline.org.uk/17/4/10.html.

WWF, Konsumentenschutz, STS (Schweizer Tierschutz), acsi (associazione consumatrici e consumatori della Svizzera italiana) and FRC (Fédération romande des consommateures) (2010) Hintergrundbericht Labels für Lebensmittel. Downloaded from: http://assets.wwf.ch/downloads/hintergrundbericht_labelratgeber_2010_def_low.pdf> accessed 08/05/14.

YIN, R K (2009) Case Study Research: Design and Methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.