Education, Social Attitudes and Social Participation Among Adults in Britain

by Lindsay Paterson

University of Edinburgh

Sociological Research Online, 19 (1) 17

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/19/1/17.html>

10.5153/sro.3235

Received: 5 July 2013 Accepted: 23 Sep 2013 Published: 28 Feb 2014

Abstract

A stable finding of research on civic participation is the correlation between overall educational attainment and various attributes that are relevant to democracy, such as propensity to be active, to vote, and to hold views on important public issues. But research since the 1990s has suggested that we should be cautious about this inference. The most important question is that raised by the findings of Nie et al. (1996) on the USA, showing that rising overall levels of education, while probably making populations more liberal, did not make them more likely to vote. Even that conclusion may be too general, because research by, for example, Campbell (2004) and Nie and Hillygus (2001) shows that the content and style of an educational course are relevant. More problematic still are questions about the nature of the citizens which education might help to create: is education democratically desirable because it makes people think, or because it makes people socially liberal (which is the general tenor of most of the writing on this topic)? The paper therefore asks, using British data, what kind of education matters for social attitudes and civic participation by adults? Several British data sources are used, mainly the 1958 and 1970 British birth cohorts, the British Social Attitudes Survey and the British Household Panel Study.

Keywords: Civic; Social Capital; Academic; Vocational; Longitudinal; Survey

Introduction

1.1 There has been a very long history of thinking about the connection between education and civic values, in which the common conclusion is that education makes people more democratically responsible in the sense of taking part in civic groups and holding liberal and tolerant views that affirm the value of democracy (Bynner and Ashford 1994; Bynner et al. 2003: 353; Cogan and Morris 2001; Denver and Hands 1990: 264; Egerton 2002a,b; Emler and Frazer 1999; Galston 2001: 219; Glaeser et al. 2006; Huang et al. 2009: 460; Lauglo and Øia 2006: 34-5, 58-61, 68-77, 78-81; Newton 1999: 18; Nie et al. 1996: 3; Niemi and Junn 1998; Zukin et al. 2006: 133-8). Such conclusions are summed up by Hall (1999), in his authoritative review of the nature and extent of social capital in Britain: 'it is well-established that each additional year of education increases the propensity of an individual to become involved in community affairs'. That was continuing in a tradition with such distinguished exponents as Thomas Jefferson, who famously wrote of his plan for education in Virginia:of all the views of this law [for public education] none is more important, none more legitimate, than that of rendering the people the safe, as they are the ultimate, guardians of their own liberty. (Jefferson 1984 [1781-2]: 274)

1.2 The empirical evidence, however, suggests that matters are not straightforward. Campbell (2006) notes in his comprehensive review of relevant research that it is not sufficient to suppose that 'education has a universally positive effect on all forms of engagement' (p. 25). For example, while '[a]cross much of the industrialised world, education levels have been rising . . . , political engagement of all sorts has been falling.' (p. 26). Even where education does have effects on civic engagement, the mechanisms of its influence are not well understood (p. 27).

1.3 The main recent academic debates on this have made six points ((a) to (f) here):

- The first is that the expansion of higher education will have been particularly likely to have made people more civic, because it is often claimed that since higher education seeks to encourage critical thinking it will enable its graduates to be better able to be critical democrats. The principle is expressed by Gutmann (1987: 173):

learning how to think carefully and critically about political problems, to articulate one's views and defend them before people with whom one disagrees is a form of moral education to which young adults are more receptive [than school children] and for which universities are well suited.

Empirical work investigating this by Egerton (2002a,b), using the young people's panel in the British Household Panel Study, confirmed that there was some evidence of effects of the kind that Gutmann suggests, although the strongest influences on young people's propensity to participate in civic ways were from their family and its social class context. - The second point from recent research is that adult learning, even that undertaken when people are in their middle age, can lead to their being more engaged in civic activities. For example, Bynner et al. (2003) have shown this in detail using the National Child Development Study for respondents between ages 33 and 42, and Feinstein and Hammond (2004) show that adult learning strengthens personal social capital. Campbell (2006: 32-3 and 108) concludes from his review that further research on the civic effects of adult learning is needed.

- These two pieces of research - by Egerton and by Bynner et al. – are quite unusual in being not from the USA, which - following the Jeffersonian tradition – is where most of the work has been done. The third point, from there, is that education might have more of an effect on attitudes than on participation. The best-known research on that point is by Nie et al. (1996), who concluded that education does encourage people to become 'democratically enlightened', but does not necessarily encourage them to participate. Much participation is like competition for a scarce resource: there is not space for everyone to participate; therefore participation will be taken up only by those who have the most educational capital, and so what matters is relative education, not absolute; Campbell (2006: 43; 2009) calls this the 'sorting model'. This argument has been refined by Helliwell and Putnam (1999) who suggest that the reference group for the competition might be local or regional rather than national. Huang et al. (2009: 461) found both an absolute and a relative effect on participation, and Milligan et al. (2002: 1692) found that, in contrast to the USA, in the UK there was no effect of education level on the propensity to vote, although voting is a special kind of participation where there is no scarcity of opportunity and thus no element of competition.

Democratic attitudes, by contrast, are not competitive in this sense: in principle everyone could be enlightened. Campbell (2006: 43) suggests this could happen in two ways - either through the absolute levels of education of individuals (such that the better educated always tend to be more civil) or through the average educational levels in a society (such that people in a well-educated community tend to take from it a general propensity to be civil). That different effects of education have been found for different dimensions of engagement suggests that a range of types of civic views and actions ought to be investigated: Campbell (2006: 28) proposes 'political engagement, civic engagement, voting, trust, tolerance, and political knowledge'. - The other three points from recent debates relate to explanations of the association between education and civic values or engagement. Nieuwbeerta et al. (2000) have suggested three kinds of motivation (and see also Heath and Topf (1986)). There is the instrumental, in which attitudes and participation serve the interests of the class to which people belong. Thus a well-educated person would be civically active not because of enlightenment but because taking a leading role in society might serve their own and their class interests. A different motive is the expressive: people hold views, or are inclined to participate, because of the socialisation which they had in childhood. In contrast, the third putative motive is acculturation, according to which these expressive ties might be gradually modified if people belong to a different social group to those in which they were brought up. Empirical testing of these theories with British data (the birth cohorts) tended to confirm the acculturation theory (Paterson 2008). If that is the most plausible, then there is a great deal of scope for education to have strong effects, both in breaking the link with childhood socialisation and also, through its actual content, shaping the character of the activism or beliefs.

- Indeed, it is the content of the curriculum to which the fifth point from recent debates relates, and insofar as variation has been found in the effects of education we might be led to question any claim that education in general is linked to civic values and participation, as most of the other points have tended to assume. Nie and Hillygus (2001), for example, have shown that social science and humanities matter more than other areas, and there have been similar findings from Denmark (Stubager 2008) from the Netherlands (van de Werfhorst and de Graaf 2004), and from Britain (Paterson 2009). Indeed, there is some evidence that some kinds of study, notably science, might in fact be associated with people becoming less engaged with politics, and technological studies have been found in some respects to be associated with people becoming less liberal (Paterson 2009). In contrast to these results, the findings of Persson (2012: 214) suggest that the reason for the observed differences in the effect of academic and vocational education is not the course content but the prior characteristics of the students and their families.

- The final point is then that it is not the overt curricular content that matters so much as the manner in which it is taught and learnt. A recurrent finding has been that the key matter is whether a course encourages independent thought. Campbell (2004; 2006: 55), for example, found that civic attitudes are encouraged by an 'open classroom environment', by which he means students' being encouraged to disagree with the teacher, the teacher's responding to students' opinions and the teacher's offering a variety of points of view on controversial issues. This climate of learning probably then depends upon and contributes to people's cognitive ability (Ceci 1991), a factor that has been found by Deary et al. (2008) and Sturgis et al. (2009) to be strongly associated with engagement and holding liberal views. So cognitive ability might be both a direct and an indirect influence on civic values and civic participation.

1.4 The purpose of this paper is to explore these matters further using a range of kinds of data relating to Britain. Are these results - many of which are from the USA - relevant to Britain? What kinds of education matter for civic purposes? Does the effect of education on an individual depend on the amount of education in the society around that person? The aim is not to cover everything - not to provide a map in the manner that Hall (1999) did for social capital in Britain. It is, rather, to investigate aspects of the questions that might test theories, and to do so from a variety of kinds of statistical data so as to assess how robust these theories might be.

Data and methods

Data

2.1 The data come mainly from three series of surveys of individual citizens, supplemented in each case by other surveys of a similar kind.

British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS)

2.2 The BSAS is an annual cross-section survey with sample size around 3,500 that has taken place since 1983 (BSAS web site). The respondents are selected by clustered, random sampling. Not all measures of interest here are asked every year, and so five years have been used to cover two decades at approximate intervals of five years (depending on the measures, and as detailed in the tables, 1986 or 1987, 1991, 1996 or 1998, 2001, and 2005 or 2006). For certain purposes, data are used also from the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey (conducted annually since 1999 with approximately the same design as the BSAS, and with annual sample size around 1,200), and the British and Scottish Election Surveys that were carried out to coincide with elections to the UK parliament in 1979, 1992 and 1997.

National Child Development Study (NCDS)

2.3 The NCDS is a longitudinal survey of a cohort of everyone born in Britain in a single week in 1958, and has followed them for half a century (NCDS web ste). The sweeps used here for measuring social attitudes and civic participation (as explained below) took place in 1991 and 2000, with some measures also from 2004. Adult educational attainment and social class are measured in 1981, 1991 and 2000, parental education and parental social class in 1974 and cognitive ability in 1974 and 1969; these educational and class measures, too, are explained below. The cohort member's sex was taken to be that which was recorded at the first sweep in 1958. For some purposes, the 1970 British Cohort Study 2000 is also used (BCS web site). It is a longitudinal study of the cohort of everyone born in Britain in a single week in 1970. Sweeps used here are from 1980, 1986, 2000 and 2004.

2.4 Although the original cohort samples had about 18,000 members, in each survey only around 2,500 cases had data present on all the variables that are used here. So multiple imputation by chained equations was used to fill the gaps, with the package 'mice' in R (van Buuren, and Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011). This procedure estimates the missing values on each variable by predicting them from a regression of its available values on all the other variables that are to be used in the modelling, and then iterating that procedure through all the variables until convergence, using 5 chains and 15 iterations. Further details of the application of the procedure to the cohort data set are provided by Paterson (2013). Nevertheless, for both cohort studies, the results without imputation were broadly similar to those reported below, probably because the models included variables that are the main predictors of non-response in longitudinal studies, such as cognitive ability and educational attainment (Nathan 1999; Hawkes and Plewis 2006).

British Household Panel Study (BHPS)

2.5 This is a panel study of households selected by clustered, random sampling and first interviewed in 1991 (BHPS web site). The annual interviews from 1991 to 2008 are used here. In order to obtain the full 18 years of measurement, only these original sample members are used, not the various supplements to the sample that were added later. The sample size was originally around 9,000 individual adults, but attrition and the omission of cases with missing values on the variables used here brought this down to about 4,000 individuals.

2.6 The British Youth Panel (BYP) is part of the BHPS: from wave 4 in 1994, children aged 11-15 in the sampled households were included, and when they reached 16 they became part of the core longitudinal sample. We analyse data from these young people when they were aged 18 - which thus span the years 1997-2008. The Youth Panel members' views were taken to be those at age 18, or at the first sweep after that when the relevant items were next asked. Since parental views are used here as an indicator of political socialisation within the family, their views were taken to be their most recent responses prior to the Youth Panel member's becoming part of the full panel: that is, at or before the sweep when the young person was aged 16. The mean of mother's and father's response (if both were present) was used to summarise parental response. Other information used is on respondent's sex, father's and mother's social class, and the educational attainment of the respondent at age 18, and, where available, of the father and the mother. There were 640 members of the Youth Panel after omitting cases with missing values.

2.7 In all the surveys, educational attainment is summarised by six-point scales recording the highest qualification obtained: no qualifications, lower than lower secondary, lower secondary (for example, GCSE, O Level, Standard Grade), upper secondary (for example, A level, Higher Grade), higher education below degree (for example, HND) and degree. Where indicated, a five-category version of this was used, combining the two higher-education categories. A distinction between academic and vocational qualifications is also used for certain purposes (Tables 8-13). The distinction is mainly as drawn in the survey documentation, and for the BSAS and BHPS is that defined by the former General Household Survey in Britain (now the General Lifestyle Survey). For the cohort surveys, a more detailed classification in the same vein is drawn from Paterson (2009). The BHPS and the birth-cohort studies record qualifications obtained between sweeps, and this information is used here as well as baseline qualifications in 1991 (for the BHPS) or when the respondent left full-time education (for the cohorts). Vocational qualifications do not include any degree-level qualifications, all of which are classified as academic. Thus in all the surveys we have measures of adult learning as well as that obtained at younger ages, and for the BHPS we have measures of annual increments in such learning. We are thus able to address Campbell's question (2006: 31) about the importance of adult learning.

2.8 In the BHPS, social class was measured by the seven-category version of the Goldthorpe scheme (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992). In the cohort studies, it was measured by an approximation to that scheme formed by a condensed version of the Registrar General's socio-economic group (see, for example, Breen and Goldthorpe 2001: 84). For parents in the cohort surveys, it was summarised by the higher of the status of father and of mother at the 1974 sweep of the NCDS and the 1980 sweep of the BCS.

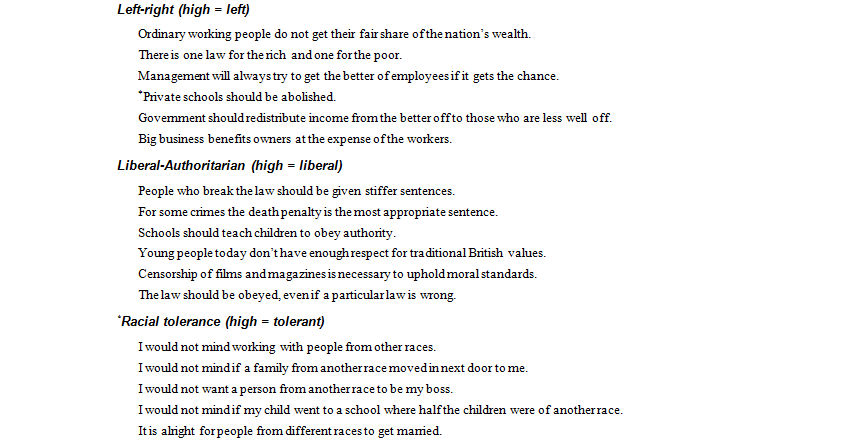

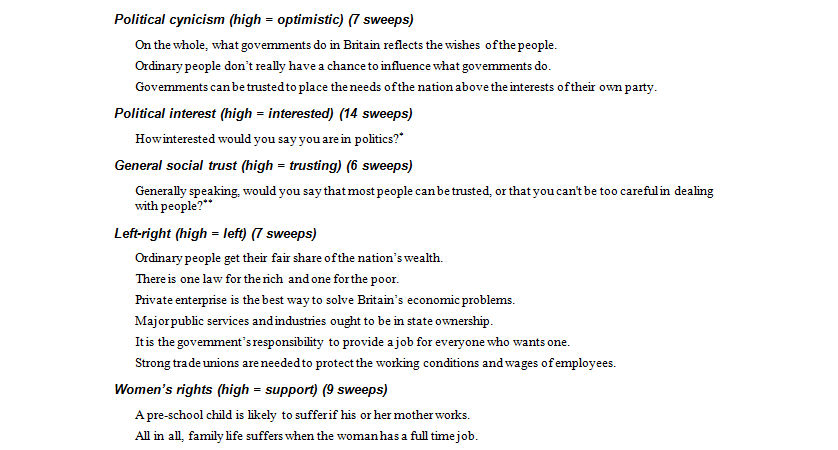

| Table 1. Questionnaire items contributing to outcome variables in the birth cohorts and the social attitudes surveys (common to both series unless noted) |

|

2.9 The dependent variables measuring social attitudes and civic participation are summarised in Tables 1 and 2, reflecting the range of dimensions of engagement recommended for research by Campbell (2006: 31). They are constructed by scoring the questionnaire items shown in the table as consecutive integers, such that all the items contributing to a scale have positive correlations with each other, and then taking the mean across items. As always in secondary analysis of diverse data sets stretching over a long period of time, the measures are not the same in the different surveys. In particular, some of the attitudes scales are available only in some of the surveys, and for other scales, although there is overlap of individual items, there are some differences between surveys. Similarly, membership of organisations is not available in all the surveys, and so for some purposes the most basic of all civic activities is used, voting in elections to the UK parliament and the Scottish parliament.

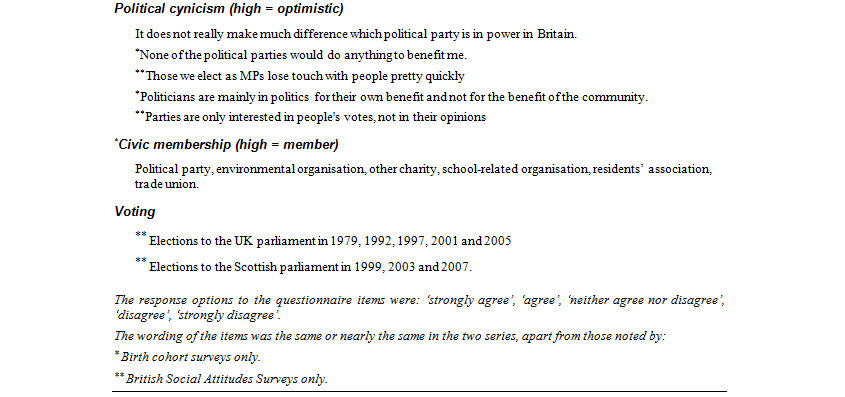

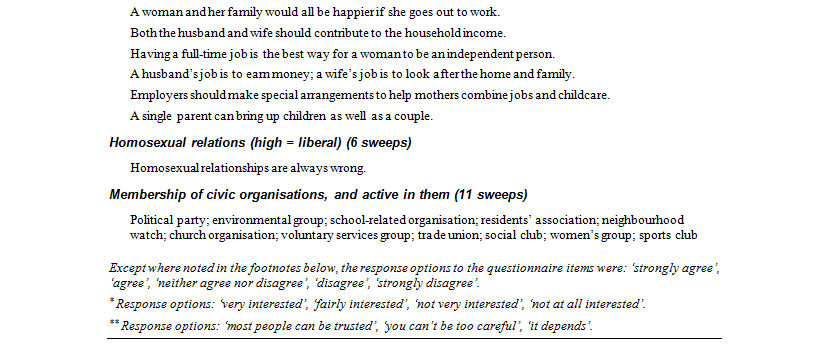

2.10 Nevertheless, as between the BSAS and the NCDS there is a great deal of overlap (Table 1), and in fact the first two scales noted there are almost identical - measuring attitudes to the economy and the role of the state ('left-right') and to civil liberties ('liberal-authoritarian'). There is also a broadly similar version of the former in the BHPS (Table 2). The scales of attitudes to the political system (labelled 'political cynicism' here) are similar but not the same in the three surveys. The scale of racial tolerance (Table 1) is available only in the birth-cohort surveys. The BHPS and BYP give a range of other scales that are not available in the other two sources (Table 2) - on interest in politics, on general social trust, and on attitudes to women's rights and to the rights of homosexual people. In the birth cohorts, there is information about participation in the civic organisations noted in Table 1. In the BHPS, there is information relating to a different but overlapping range of civic organisations, as noted in Table 2.

| Table 2. Questionnaire items contributing to outcome variables in the British Household Panel Study and British Youth Panel, 1991-2008 (and the number of survey sweeps when the scale was measured) |

|

2.11 One later sweep of the NCDS (in 2008) did record some of the information summarised in Table 1, but not for the full set of items except in relation to the political cynicism scale and the membership measures. So as not to weaken further the comparability with the other surveys, that 2008 sweep is not used here (but see Paterson (2013)).

2.12 Despite the discrepancies of measure, therefore, it is hoped that the breadth of coverage and the diversity of kinds of data - cross-sectional, panel data and long-term cohort studies - are valuable enough to compensate for the loss of exact comparability. In any case, no attempt is made to compare measures directly across surveys. The interpretation concentrates always on the relationship of educational attainment with the various outcomes.

Methods

3.1 The data from the BSAS are used mainly for introductory and descriptive purposes, because that series provides the least information about education and the least scope for investigating detailed links between education and attitudes or participation. The advantage of the BSAS is that it draws a fresh sample every year and thus is reliably able to measure change over time.

3.2 The basis of all the analysis is linear regression; using logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes gave very similar patterns of results to those shown here. The association with education is measured by including in the models the six-category or five-category summary of highest educational attainment as a set of indicators of differences from the reference category of 'no qualification'. Where required, control variables were added as noted below; where such a variable was categorical (for example, social class) it too was entered as a set of indicators. The purpose of controls is to enable estimation of the direct effect of education, rather than effects that are through, for example, early socialisation or current social class. This basic modelling was done in R.

3.3 A refinement of this simple structure was used for the BHPS. The structure of the data is of repeated measures over several sweeps (the number noted for each measure in Table 2). Therefore some account has to be taken of serial correlation between the same measure collected on successive occasion, especially in order to be able to assess the association with new educational attainment between sweeps. The essence of the model is then as follows. Let yti be the response (on some particular measure) of panel member i at sweep t. Let qi be the baseline educational attainment of that panel member at sweep 1, and let xti be the attainment since the most recent sweep before sweep t when the response was recorded (for t equal to those occasions from 2 to 18 when the response was recorded). The structure is then a two-level model of time points within panel members:

yti = b0 + b1qi + b2 xti + ui + etiin which b1 is the general association of attainment with the measure, and b2 is the association with attainment since the previous occasion on which the response was recorded. Further refinement to the model can be obtained by adding control variables to the right-hand side of the equation - for example, age, social class or sex.

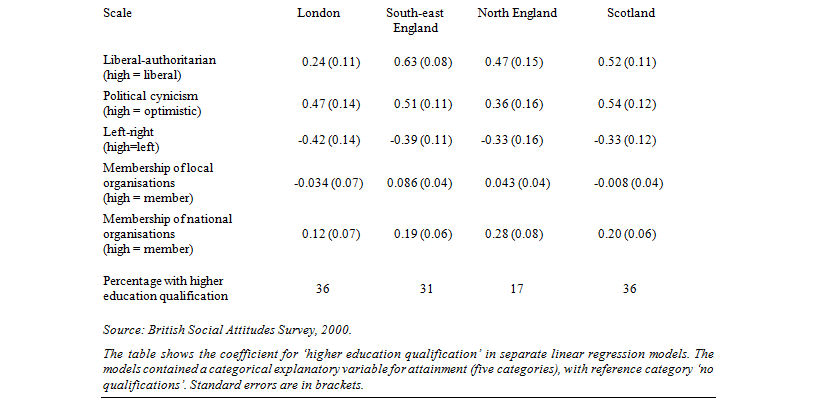

3.4 The term ui is simply the un-measured heterogeneity among panel members. The autocorrelation of the response between occasions can be captured in the error structure that is imposed upon the final term in the equation, which is the random variation for respondent i at time t. The Durbin-Watson statistic calculated for the responses showed that there was indeed autocorrelation between responses by the same individual on successive occasions. In principle, the structure of the autocorrelations could be complex, but Rasbash et al. (2009: 74-9) provide a convenient way of estimating a linear autocorrelation in the multilevel modelling package MLwiN, and that turned out to be sufficient here. According to this linear structure, the covariance between the error terms on two occasions t1 and t2 is:

in which the term α is to be estimated. The autocorrelation is then α divided by the residual variance of the e terms. When this model was run (using MLwiN) for each of the responses in the BHPS, calculating a Durbin-Watson statistic for the resulting residuals showed that there was no longer evidence of autocorrelation.

3.5 The BYP, because it had only a relatively small sample, is modelled with linear regression, neglecting the chronological structure of the data. However, a crude allowance for time trends in the dependent variable is made by including among the explanatory variables a linear term recording the year in which the respondent turned 18.

3.6 In order to include the broad range of surveys and measures, it is not possible to present the details of the analysis of all measures for each survey. So in several aspects of the presentation of findings, selected measures are given, illustrating the main points. Similarly, considering in detail all aspects of the association between educational attainment and the outcome measures is not feasible here, and so the association with education is mostly illustrated in terms of the effects of holding a degree, or more generally any kind of higher-education qualification. For reasons noted in the Introduction, these are the most interesting categories in recent decades, because of the expansion of higher education and because of the claims made by some authors (such as Gutmann 1987) that higher education is particularly conducive to civic values. The proportion of respondents in the BSAS of 1986 who held a higher education qualification was 19%; in 2006, it was 29%. The proportion specifically with a degree rose from 7% to 17%. Nevertheless, despite concentration on higher education, sheaf coefficients (Heise 1972), encapsulating the whole effect of the education variable, were also calculated, and in all cases showed patterns that were similar to those shown by the coefficient for higher education; these are not reported further here.

Results

4.1 Throughout the presentation of results, the concentration is on four sets of questions that are derived from the discussion which was summarised in the Introduction:

- The most basic question arises from the points (a) and (b) raised by that discussion - to test whether, during the recent expansion of higher education and of lifelong learning, the association between it and civic attitudes or civic participation has remained strong (as Hall (1999), for example, might be taken to suggest). We saw also in point (c) earlier that Nie et al. (1996) were sceptical about the most general claims for the effects of education, finding that that there might be a constant effect on attitudes but a declining effect on participation. The basic question and the questions raised by Nie et al are dealt with in the first section below.

- The refinement from Helliwell and Putnam (1999), in reply to Nie et al., that there might be variation in any effect by regional educational context, is dealt with in the second section below.

- and (4) The third and fourth sections below relate to points (e) and (f) in the discussion earlier, concerning the content and manner of learning - whether some curricular areas (section (3) below), and some types of learning (section (4) below), are more conducive to civic attitudes or participation than others. Point (d) from the earlier discussion (whether motivation is instrumental or expressive or a matter of acculturation) is used in the final section of the paper to suggest some sociological explanations.

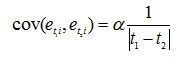

(1) Educational expansion and types of civic effects

4.2 First we look at the evidence from the BSAS in Table 3, which displays variation over time (from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s) in the coefficient of 'higher education' in simple regressions which relate the scales shown to the five-category education variable. The striking feature is that there is no single pattern. For the political-cynicism and to some extent the left-right scales, there is declining association. That is, holding a higher-education certificate (when compared to holding no qualifications at all) is less strongly associated with being optimistic about politics at the end of the period than at the beginning, and is also less strongly associated with position on the left-right scale. In contrast, there is some rise in association of higher education with being liberal (as opposed to authoritarian). There is no evidence that the growth of higher education has led to a weakening of the association between taking part in it and voting, and indeed, if anything, there is some (though not strong) evidence that the association might have strengthened. None of this is consistent with Nie et al. (1996).

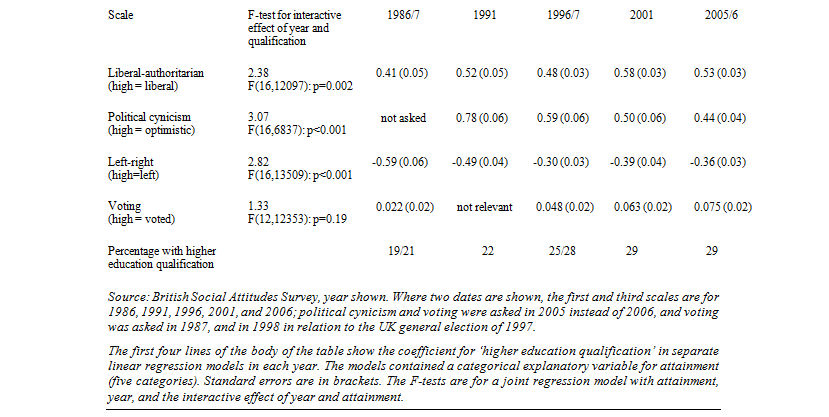

4.3 That analysis has the advantage of looking at change over two decades during which participation in higher education rose by one half. However, the main weakness of such an approach is that it conflates birth cohorts, when in fact it was in younger groups that participation in higher education rose most sharply. Re-doing the analysis in Table 3 for different synthetic cohorts (comparing those born before 1940 with those born after 1960) showed no consistent tendency for any cohort effects, but a more satisfactory way of allowing for cohort is to use the second main source of data, the birth cohorts. The two birth cohorts conveniently span a period when there was a large rise in degree-level attainment: 12% of cohort members in the NCDS held a degree at age 33, while 21% did so in the BCS at age 30. Results are in Table 4, showing the effect of holding a degree, with and without control for other predictors. Comparing first the two sweeps of the NCDS, a decade apart, we can see that the coefficients do not change much at all.

| Table 3. Association of holding a higher-education qualification with scales of social attitudes and with voting, 1986-2006 |

|

| Table 4. Association of holding a degree with attitudes and membership: effects of age and of cohort |

|

4.4 This absence of change excludes there being much of an age effect. Another way of assessing any sources of change is to hold age constant, and compare the NCDS with the later birth cohort at similar ages - the first and third columns. The only evidence of change that is the same direction as in the BSAS is in political cynicism, where the association with holding a degree weakens. For the libertarian-authoritarian scales, there is a weakening here but there may have been a strengthening with the BSAS. The opposite contrast is true of the left-right scale. There is otherwise no tendency to confirm the BSAS results, nor, again, to confirm Hall or Nie et al.. A weakening effect on political cynicism and on libertarian-authoritarian views runs directly counter to their theories.

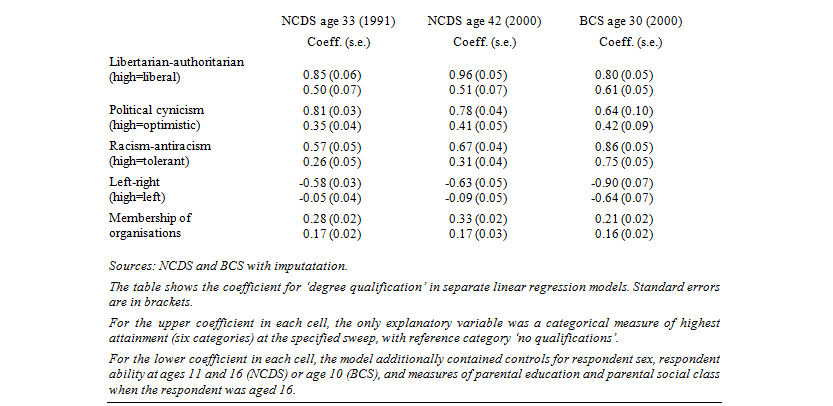

(2) Regional educational context

4.5 Helliwell and Putnam, as we saw, responded to the theory of Nie et al. by proposing a regional aspect to any tendency for education to be associated with civic participation. So we look specifically next at selected geographical areas.

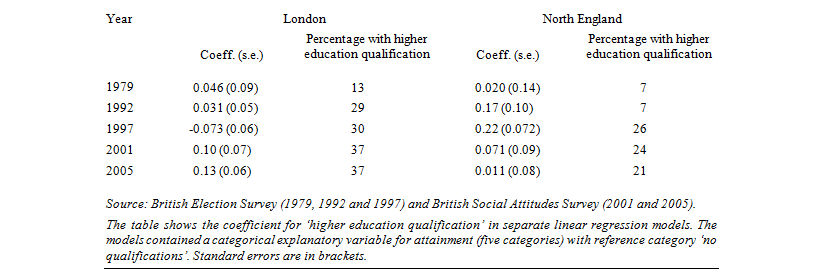

4.6 Table 5 compares the regression coefficients for four illustrative areas in the year 2000 - London, South-east England, northern England, and Scotland; the reason for taking that year is that the BSAS asked about membership of organisations then, both locally (for example, residents' associations, parents' associations) and nationally (for example, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Greenpeace) (Paterson 2002). The main point to note in respect of attitudes is that there is variation in the association with holding a higher-education qualification, but not in any way that follows the level of higher education in the area (as shown in the bottom row of the table): there is no consistent tendency for the area with the lowest level of higher education (northern England) to have the highest or lowest association of higher education with attitudes; and the two areas with equally high levels of higher education - London and Scotland - have quite different patterns of association. There is hardly any association of membership of local organisations with holding a higher education qualification. The pattern of association with membership of national organisations no more than loosely follows that predicted by Helliwell and Putnam: the coefficient is indeed lower in London and south-east England than in northern England, but it is lower in London also than in Scotland where educational levels are at the same levels as in London.

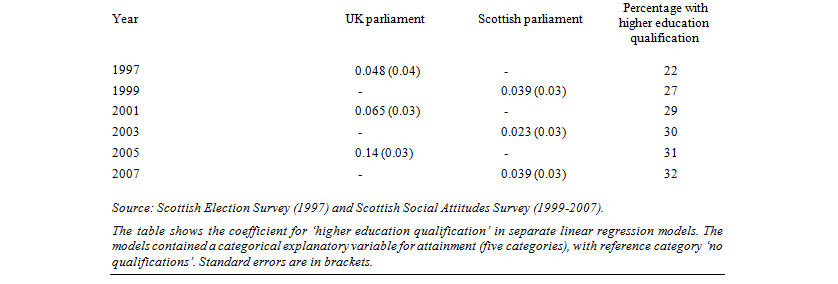

4.7 Membership may be specific to the organisations examined, and so perhaps a more universal test is voting (Tables 6 and 7). Table 6 compares London and northern England, showing the association between voting and holding a higher-education qualification for five general elections to the UK parliament from 1979 to 2005. There is no trend consistent with the Helliwell and Putnam prediction: in London, as the contextual level of higher education rose from 13% in 1979 to 37% in 2005, there was, if anything, a slight tendency for the individual-level association between voting and higher education to strengthen. There is no discernible pattern at all in the values of the association in northern England. The first column of Table 7, for Scotland, is not consistent with the prediction either: Scotland resembles London only in that same year, 2005. So voting for the UK parliament gives little support to the prediction that high local levels of education make the association between participation and education weaker.

4.8 The main purpose of Table 7, on Scotland, is to show a different point, which is that there seems to be an effect of political system that is not encapsulated in the theories outlined in the Introduction. The first column there shows the association in Scotland between holding a higher-education qualification and voting in elections to the UK parliament. The second column shows the analogous associations for elections to the Scottish parliament. The latter association is consistently weaker.

| Table 5. Association of holding a higher-education qualification with scales of social attitudes and with membership of organisations, by selected area, 2000 |

|

| Table 6. Association of holding a higher-education qualification with voting by selected area in England, 1979-2005 |

|

| Table 7. Association of holding a higher-education qualification with voting in Scottish elections by level of parliament, 1997-2007 |

|

(3) Broad curricular area

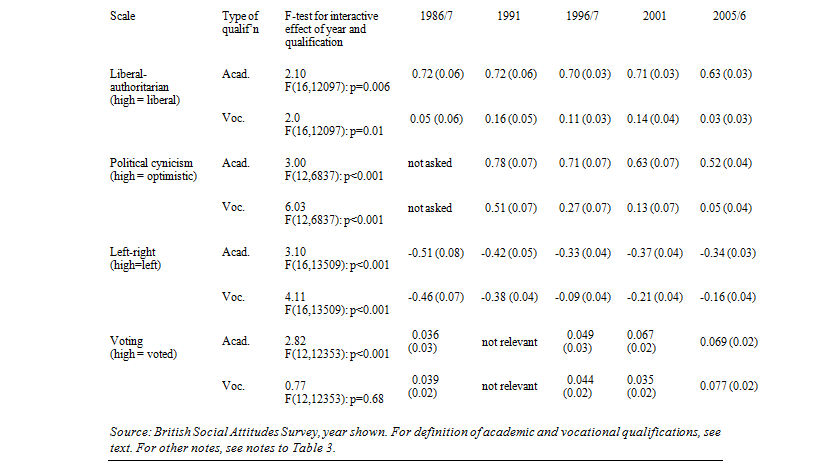

4.9 Few of the theories summarised in the Introduction draw any distinctions among different kinds of education. Most data sets do not allow these to be drawn readily either, but there is often the possibility of distinguishing between academic and vocational courses, especially in the post-school advanced sector that is our main focus here. Table 8 returns to the same BSAS data sets and topics as Table 3, now showing separately the association with academic and with vocational attainment. The pattern is fairly clear. For the liberal-authoritarian and political-cynicism scales, there is a much stronger association with academic education than with vocational education. That is probably also true for the left-right scale, although the difference is smaller and less surely established. There is no consistent difference on the voting measure.

| Table 8. Association of holding an academic or vocational higher-education qualification with scales of social attitudes and with voting, 1986-2006 |

|

| Table 9. Association with attitudes and membership at age 33 of academic and vocational higher education education between ages 23 and 3 |

|

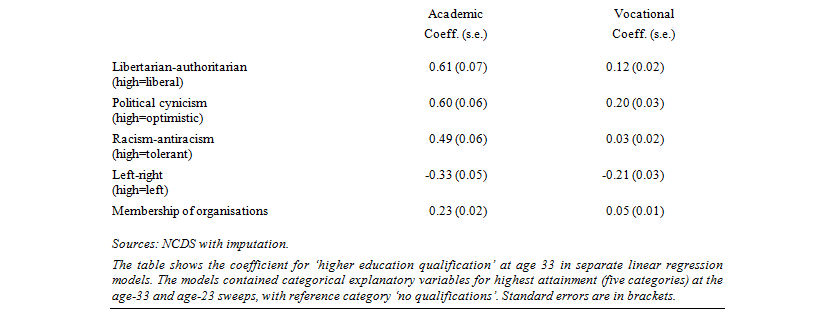

4.10 As with Table 3, we might still ask whether the mixture of age cohorts in the BSAS samples is confusing trends here, but similar conclusions can be drawn holding cohort constant, in Table 9, which uses the NCDS to show the association of attitudes and membership with holding an academic or a vocational higher-education qualification. Here the evidence is very clear: academic qualifications are more strongly associated with attitudes and with membership than vocational qualifications.

4.11 An alternative longitudinal test is available from the BHPS, modelling the effects on attitudes and on participation of courses taken between two time points. There is a great deal of course-taking in the 18 years of the data from that survey used here. Between any two yearly waves, around 3-4% of respondents had gained a new academic qualification and some 1-2% had gained a new vocational qualification. Over the whole period, 24% of respondents had gained at least one academic qualification and 11% had gained at least one vocational qualification. So, allowing for correlated errors as explained in the Methods section, we can assess the effects of academic and vocational courses on attitudes and membership shortly after.

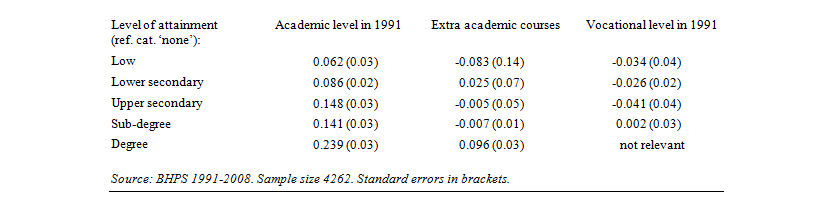

4.12 The results over the range of measures are exemplified in Tables 10-13. Table 10 is for political cynicism. The strongest association of an educational variable with the scale is baseline academic achievement (when the panel started in 1991): broadly, the higher the respondent's achievement the less cynical they are. By contrast, baseline vocational achievement (final column) has no association with the response on this scale (and the same was true of the variable recording extra vocational qualifications, and so it is not included in the model shown here). The closest we have to a causal test, however, is in the middle column for taking extra academic courses between one occasion on which this scale was measured and the next. Taking an extra academic degree was associated with the respondent's being less cynical, reinforcing the effect on attitudes of previous academic attainment.

| Table 10. Repeated-measures model of political cynicism (high = optimistic) |

|

| Table 11. Repeated-measures model of political interest (high = interested) |

|

| Table 12. Repeated-measures model of generalised social trust (high = trusting) |

|

| Table 13. Repeated-measures model of attitude to women's rights (high = support) |

|

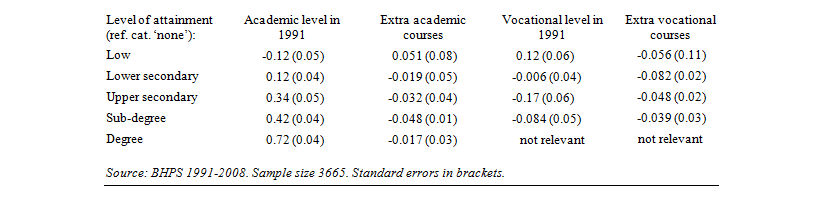

4.13 The second example (Table 11) shows a different pattern, here for political interest. There is a very strong association with baseline academic qualifications, political interest rising across the rising levels of education. Unlike with political cynicism, taking an extra academic degree does not have any effect on that (coefficient of -0.017 (s.e. 0.03)), and indeed taking a sub-degree academic qualification slightly weakens the tendency for such qualifications to be associated with political interest (-0.048 (s.e. 0.01)). There is some evidence, too, that higher levels of vocational qualification, whether at the baseline or later, weaken the association with political interest, insofar as the coefficients for upper secondary vocational courses are negative, whether in the baseline or in extra qualifications. There is also an interesting point at the other end of the spectrum of attainment: whereas very low levels of academic attainment are associated with lower political interest than being in the reference category of having no academic attainment at all, the opposite is true of very low levels of initial vocational qualifications (0.12 (s.e. 0.06)). Vocational success at low levels of achievement may engage people more with the political system than academic success only at these levels, whereas vocational success at higher levels may have the opposite effect.

4.14 Since many other authors have analysed effects on generalised social trust (for example, Sturgis et al. (2010) and Huang et al. (2009)), it is informative to look at that outcome here: Table 12. Again, there is the familiar pattern of a strong association with baseline academic achievement. There is no association with any level of vocational attainment below higher education, and a weak association with that (0.048 (s.e. 0.023)). Notably, though, taking extra academic courses at sub-degree level somewhat weakens the positive effect of academic education on trust (-0.029 (s.e. 0.012)).

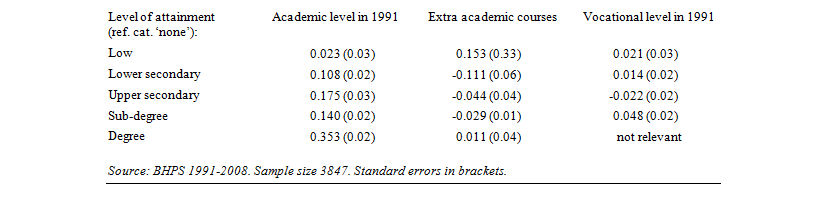

4.15 A final illustration of the longitudinal modelling of attitudes from the BHPS is in connection with attitudes to women's rights, in Table 13. In a general pattern of almost no educational effects, the one clear exception appears to be for degree-level academic qualifications, which show a strong positive association with supporting women's rights. This association was not weakened when respondent's sex was added to the model as a control: thus both sexes seem to become more in favour of women's rights when they gain an academic degree. However, support for women's rights and gaining an academic degree are both associated with age, younger people being more likely to support these rights and to hold that qualification. In a further model which added respondent's age as a control, the association with holding a degree vanished (becoming 0.012 (s.e. 0.03)). Indeed, holding a sub-degree academic qualification was then associated with having a less positive view of women's rights (-0.054 (s.e. 0.027)), and, moreover, taking an extra academic degree or sub-degree qualification had a similar negative association (respectively -0.040 (s.e. 0.019) and -0.019 (s.e. 0.008)). Thus it is age more than education that explains attitudes to women's rights.

4.16 We can summarise this analysis of academic and vocational education by saying that not all education has a positive effect, or indeed any effect, on civic values or participation. On the whole, academic study seems to have stronger effects on civic values and behaviour than vocational study. This is consistent with the evidence summarised in the Introduction on the importance of curriculum. Some effects depend on the age at which a course is taken: for example, some kinds of courses taken in adulthood appeared to weaken political interest (Table 11). There might also be important period (or contextual) effects, for example on women's rights.

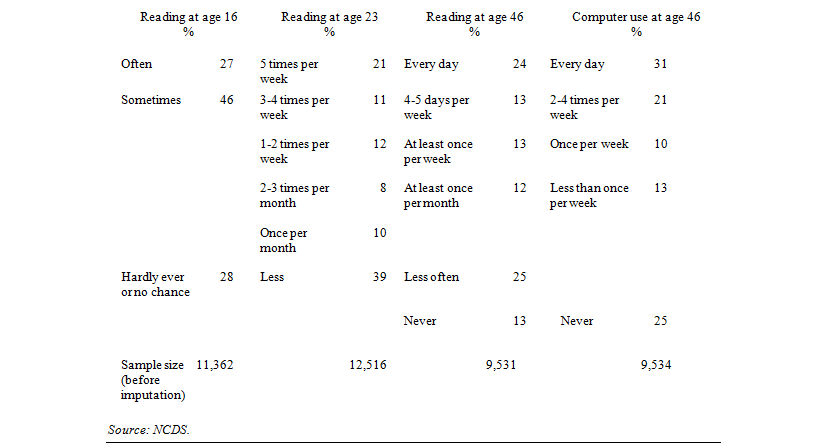

(4) Manner of learning

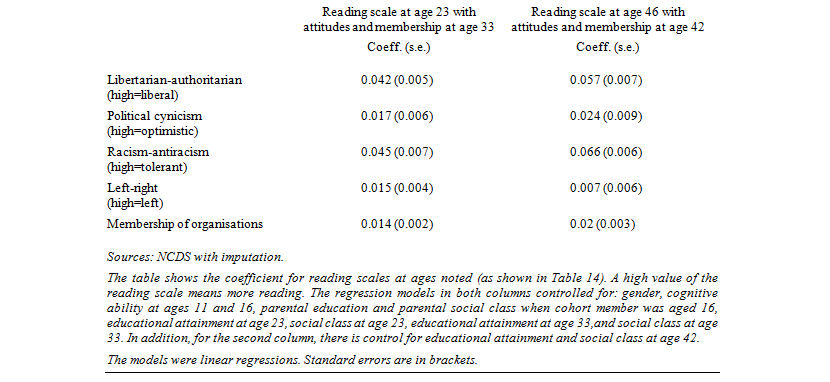

4.17 We noted in the introduction the evidence from other studies that being encouraged to think independently was associated with being more engaged with civic matters. None of the data sets contains direct measures of such pedagogical experiences, but in the NCDS there are measures of reading books for pleasure. For comparison, but only at later ages, there is also information about computer use. The question responses summarised in Table 14 show the levels of reading for pleasure at ages 16, 23 and 46; the questionnaire wording emphasised that what was being asked about was not to include reading educational textbooks (ages 16 and 23) or for work or study (at age 46). Around a half of the sample read books often, and perhaps a quarter to around a third rarely did so.

4.18 These scales were entered into regression equations as continuous covariates (scored in consecutive integer values with the highest corresponding to the most frequent reading), and controlling for the variables noted in the footnote to Table 15. The result in Table 15 is clear and almost entirely consistent: even after all these controls, at both ages reading for pleasure was associated with being more liberal, less politically cynical, more racially tolerant, and more civically active. At age 23 only, reading is also associated with being more left-wing. The pattern of results at age 46 was the same if the age-23 measure was used (and in fact was very close to the pattern for age 33 shown in the table). It was also very similar at each age if the age-16 measure was used. Thus reading reinforces the effects of education, except perhaps on the left-right scale for which it may have an opposite effect.

4.19 The association with reading is stronger and more consistent than the association with computer use. The last column of Table 14 showed that computer use at age 46 was broadly at the same level as reading at that age, but the correlation between them was low (0.17, calculated as either a Spearman or a Pearson coefficient). Table 16 shows the results at age 42 of putting both the age-46 reading scale and the age-46 computer-use scale into the models. The coefficients for the reading scale differ from those in the second column of Table 15 only because of the addition of the computer-use scale, and that they are nearly identical reflects the low correlation of these two scales. On four of the response scales, the association with computer use is in the same direction as the association with reading, but is notably weaker. On the left-right scale, the association is in the opposite direction to that with reading.

| Table 14. Frequency of reading books and of computer use, 1958 cohort |

|

| Table 15. Association of reading scales with attitudes and membership |

|

| Table 16. Association of reading and computer-use scales (age 46) with attitudes and membership (age 42) |

|

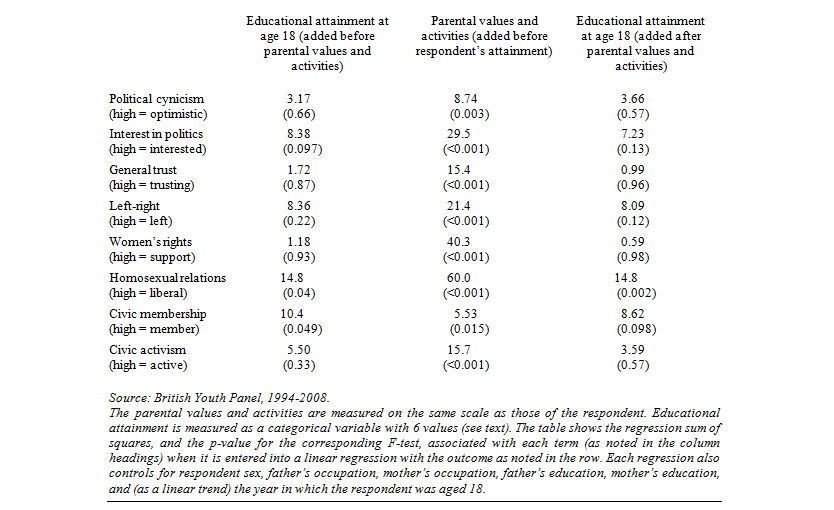

4.20 Informal self-education thus appears to influence civic values and a propensity to participate. The relevant habits may be laid down by age 16, and a further source of data suggests that civic influences from the family are stronger at this young age than any influences from formal education. The British Youth Panel allows us to compare the influence of formal education with the influence of parental values and propensities measured in exactly the same way as for the young people themselves. Each regression also controls for respondent sex, father's occupation, mother's occupation, father's education, mother's education, and (as a linear trend) the year in which the respondent was aged 18. Table 17 summarises the results. For each measure of young people's civic values and participation, the table shows the regression sum of squares associated with formal attainment and with the same civic measure for parents, and the p-value for the corresponding F-test. Not shown in the table is that, in each case, the regression coefficient linking the young person's and the parents' views or activities was strongly positive, and also that the association with the young person's educational attainment was consistent with the patterns we have seen in other data sets. With one exception - membership of civic organisations - the sum of squares for the parental measure is greater than that for formal attainment. In all cases except attitudes to homosexual relationships the p-value for the association with attainment is above 0.05 after adding the parental measure, whereas (in details not shown) the p-value for the parental measure remained below 0.05 even after adding formal attainment. Thus family socialisation does seem to matter more than formal education (as Egerton (2002a,b) noted for participation, using an earlier part of this time series).

| Table 17. Association of young people's civic values and activities with educational attainment and with parental civic values and activities |

|

Discussion

5.1 For Britain, there might thus appear to be no neat conclusions about trends, if we follow the theories that have been invoked in connection with the USA. The effect of education on civic values and on activism is not uniform over time: for some it strengthens, for some it weakens, and for some it broadly remains the same. The general claims for education and civic values are just too simple; it is still the case, as Heath and Topf argued using data from 1983, that 'we must be careful to avoid any simplistic theory of educational causation' (heath 1986: 565). Moreover, the variation is not as neat as predicted by Nie et al. (1996) or by Helliwell and Putnam (1999).5.2 Nevertheless, our further analysis suggests different kinds of patterns that might provide more pedagogically cogent explanations than in terms of broad secular trends. One is that how people respond to education in a civic sense depends on political context. An example was in the contrast in Scotland between voting for the Scottish and UK parliaments. It is not just that participation is lower in the former than in the latter elections; it is also that the association with education is weaker. A more subtle point about the importance of political context emerged from the effects of age on attitudes to women's rights: if age was a surrogate for period of political socialisation, then we can say that the apparent effect of holding a degree in making people more inclined to support these rights was due not to that education as such but rather to the period through which people born after the 1960s have lived. They gained new educational opportunities because of the expansion of higher education, and they learned new understandings of gender because that was the major social change of the period. These two secular trends may be related in some general way, insofar, for example, as being able to gain entry to the professions in greater numbers enabled more women to have prominent roles in public life, and this public presence may have influenced attitudes towards women's careers. But the influence of education on attitudes to rights was, at most, by that indirect route, not directly at the level of the individual, because - in the model - people of similar ages held similar views regardless of the amount of education they had had.

5.3 The other reason for variation in the measured effects of education is that the kind of education that people have matters. It is possible to have quite a lot of education - for example, vocational higher education, or a science degree (Paterson 2009) - and yet to have gained nothing in a civic sense from it. Although the main conclusion concerning vocational education is that it had little effect, in some instances it was associated with views that were less civic as conventionally defined - for example (in Table 11) perhaps making people less interested in politics. So any growth of vocational education - as strongly urged by policy makers - if it was in place of academic education (which it would be almost bound to be) would probably make education less relevant to civic values, and may make people less liberal and less likely to participate. The longitudinal analysis of panel data (from the BHPS) confirms the finding of Feinstein and Hammond (2004) that adult learning of an academic kind matters, and suggests that one way in which general intelligence has an impact on social trust - as found by Sturgis et al. (2010) - is through academic far more than through vocational study.

5.4 This interaction with educational content ought to be the least surprising conclusion to those who study education in detail, and it may be that the tendency to generalise about the effects of education on civic life is tempting only if curricula and pedagogy are ignored. The matter is more complex than that, however, because it seems not to be merely the content of what is offered to students that matters but also the manner in which students respond to it. As well as the prior research showing the importance of independent thought for civic engagement, there is the finding from the data we have examined here that the independent reading of books influences people quite consistently to be more active and to hold liberal, tolerant and politically engaged views. Independent reading also may incline people to the left politically, unlike education in general which tends in the opposite direction. Formal education in school is less important in explaining young people's civic values and propensity to participate just after age 18 than the informal influence of their parents.

5.5 Thus the conclusion of the analysis may in fact run counter to one likely sociological reading of the purposes of the present special issue, the supposition which Nieuwbeerta et al. (2000) referred to as the expressive explanation, according to which people hold views that reflect their initial socialisation. The evidence we have looked at here suggests that matters are not nearly so straightforward. Though it is true that, at a fairly young age, family socialisation seems to be more influential than education, that is not true at older ages. The rising participation of young people in higher education in the past thirty years has not led to a constantly rising participation in civic life, nor to a steady trajectory towards more liberal views. An important topic for further research would then be the manner in which cultural resources acquired in early life, and thus reflecting the norms of a family, are translated later, through education, into a capacity for autonomous judgement on civic matters. Such research might be designed to extend longitudinally into adult life the careful delineation of cultural knowledge that Sullivan (2007) provided for a sample of school students.

5.6 But neither also are the patterns to be readily explained instrumentally, Nieuwbeerta et al. (2000)'s second explanation. The tendency of well-educated people to hold economically right-wing views might be interpreted in that way, insofar as the well-educated would tend to benefit personally from less state involvement in the economy because of the generally professional class positions that they tend to occupy, but no such instrumental explanation readily presents itself for the association of higher education with views that are liberal or anti-racist, and with a less cynical attitude to politicians. Moreover, the association of reading for pleasure with left-wing views would suggest a survival into a much more educated age of the tradition of the autodidact socialist (Rose 2001).

5.7 Thus the sociological explanation from Nieuwbeerta et al. (2000) that works best here is what they call 'acculturation', the tendency of people to move towards the characteristic views of social groups to which they come to belong. In this interpretation, the young absorb the views of their parents only because they are still close to them, but, for adults, what matters is how they respond to new social contexts. It is then the educational content of learning, and people's understanding of that, which are important in understanding its effect, and a sociological explanation that paid no attention to curricular or pedagogical characteristics would not adequately capture why and how education is influential.

5.8 Educational expansion may be good for democracy in that it may encourage the well-educated to be civic and to be active. They are equipped to think independently and then they take that independent thought into both their own further enlightenment and into the roles which they play in social networks. There is no evidence from the wide range of British data we have analysed here that these civic effects weaken as overall education expands, but neither are they uniform. The main conclusion from the analysis is thus that education is not automatically a source of democratic enlightenment: as with all the other effects that education may have, its civic effects depend on what learners do with it.

References

BREEN, R and Goldthorpe, J (2001) 'Class, mobility and merit: the experience of two British birth cohorts', European Sociological Review, Vol. 17, p. 81-101. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1093/esr/17.2.81]BRITISH COHORT STUDY web site, <http://cls.ioe.ac.uk/page.aspx?&sitesectionid=795&sitesectiontitle=Welcome+to+the+1970+British+Cohort+Study>.

BRITISH HOUSEHOLD PANEL STUDY web site, <https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/bhps>.

BRITISH SOCIAL ATTITUDES SURVEY web site, <http://www.natcen.ac.uk/series/british-social-attitudes>.

BYNNER, J and Ashford, S (1994) 'Politics and participation: some antecedents of young people's attitudes to the political system and political activity', European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 24, p. 223-36. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240202]

BYNNER, J, Schuller, T and Feinstein, L (2003) 'Wider benefits of education: skills, higher education and civic engagement, Zeitschrift für Pädagogik', Vol. 49, p. 341-61.

CAMPBELL, D E (2004) Voice in the classroom: how an open classroom environment facilitates adolescents' civic development. Notre Dame, IN: Department of Political Science, University of Notre Dame.

CAMPBELL, D E (2006) What is education's impact on civic and social engagement? Symposium on Social Outcomes of Learning (23-24 March 2006), Copenhagen: Danish University of Education.

CAMPBELL, D E (2009) 'Civic engagement and education: an empirical test of the sorting model', American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 53, p. 771-86. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00400.x]

CECI, S J (1991) 'How much does schooling influence general intelligence and its cognitive components? a reassessment of the evidence', Developmental Psychology, Vol. 27, p. 703-22. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.703]

COGAN, J J and Morris, P (2001) 'The development of civic values: an overview', International Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 35, p. 1-9. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0883-0355(01)00002-7]

DEARY, I, Batty, G D and Gale, C R (2008) 'Bright children become enlightened adults', Psychological Science, Vol. 19, p. 1 - 6. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02036.x]

DENVER, D and Hands, G (1990) 'Does studying politics make a difference? The political knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of school students', British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 20, p. 263-79. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400005809]

EGERTON, M (2002a) 'Higher education and civic engagement', British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 53, p. 603-20. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0007131022000021506]

EGERTON, M. (2002b) 'Family transmission of social capital: differences by social class, education and public sector employment', Sociological Research Online, Vol. 7, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/7/3/egerton.html>. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.5153/sro.747]

EMLER, N and Frazer, E (1999) 'Politics: the education effect', Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 25, p. 251-73. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/030549899104242]

ERIKSON, R and Goldthorpe, J H (1992) The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

FEINSTEIN, L and Hammond, C (2004) 'The contribution of adult learning to health and social capital', Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 30, p. 199-21. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0305498042000215520]

GALSTON, W A (2001) 'Political knowledge, political engagement and civic education', Annual Review of Political Science, Vol. 4, p. 217-34. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.217]

GLAESER, E L, Ponzetto, G and Shleifer, A (2006) Why does democracy need education? NBER Working Paper 12128, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

GUTMANN, A (1987) Democratic Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

HALL, P (1999) 'Social capital in Britain', British Journal of Politics, Vol. 29, p. 417-61. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0007123499000204]

HEATH, A and Topf, R (1986) 'Educational expansion and political change in Britain: 1964-1983', European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 14, p. 543-67. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1986.tb00849.x]

HEISE, D R (1972) 'Employing nominal variables, induced variables, and block variables in path analyses', Sociological Methods Research, Vol. 1, p. 147-73. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1177/004912417200100201]

HELLIWELL, J F and Putnam, R D (1999) Education and social capital. Working paper 7121, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research).

HUANG, J, van den Brink, H M and Groot, W (2009), 'A meta-analysis of the effect of education on social capital', Economics of Education Review, Vol. 28, p. 454-64. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2008.03.004]

JEFFERSON, T (1984 [1781-2]) Notes on the State of Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library).

LAUGLO, J and Øia, T (2006) Education and Civic Engagement among Norwegian Youths. Oslo: Norwegian Social Research.

MILLIGAN, K, Moretti, E and Oreopoulus, P (2004), 'Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom', Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 88, p. 1667-95. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.10.005]

National Child Development Study web site, <http://cls.ioe.ac.uk/page.aspx?&sitesectionid=724&sitesectiontitle=National+Child+Development+Study>.

NEWTON, K (1999) Social capital and democracy in modern Europe, in: van Deth J W, Maraffi M, Newton K and Whiteley P F (Eds) Social Capital and European Democracy, London: Routledge.

NIE, N and Hillygus, D S (2001) Education and democratic citizenship, in Ravitch D and Vitteriti J P (Eds) Making Good Citizens, New Haven: Yale University Press.

NIE, N H, Junn, J and Stehlik-Barry, K (1996) Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

NIEMI, R G and Junn, J (1998) Civic Education: What Makes Students Learn. New Haven: Yale University Press.

NIEUWBEERTA, P, de Graaf, N D and Ultee, W (2000) 'The effects of class mobility on class voting in post-war western industrialised countries', European Sociological Review, Vol. 16, p. 327-48. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1093/esr/16.4.327]

PATERSON, L. (2002) Social capital and constitutional reform, in Curtice, J, McCrone, D, Park, A and Paterson, L (Eds) New Scotland, New Society?, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

PATERSON, L (2008) 'Political attitudes, social participation and social mobility: a longitudinal analysis', British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 59, p. 413-34. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00201.x]

PATERSON, L (2009) 'Civic values and the subject matter of educational courses', Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 35, p. 81-98. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03054980802351801]

PATERSON, L (2013), 'Comprehensive education, social attitudes and civic engagement', Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, Vol. 4, p. 17-32.

PERSSON, M (2012), 'Does type of education affect political participation? Results from a panel survey of Swedish adolescents', Scandinavian Political Studies, Vol. 35, p. 198-221. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2012.00286.x]

RASBASH, J, Charlton, C, Jones, K and Pillinger, R (2009) Manual supplement for MLwiN Version 2.14. Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling.

ROSE, J. (2001) The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. New Haven: Yale University Press.

STUBAGER, R (2008) 'Education effects on authoritarian-libertarian values: a question of socialization', British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 59, p. 327-350. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00196.x]

STURGIS, P, Read, S and Allum, N (2010), 'Does intelligence foster generalized trust? An empirical test using the UK birth cohort studies', Intelligence, Vol. 38, p. 45-54. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2009.11.006]

SULLIVAN, A. (2007), 'Cultural capital, cultural knowledge and ability', Sociological Research Online, Vol. 12, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/6/1.html>. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.5153/sro.1596]

VAN BUUREN, S, and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K (2011) 'mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R' Journal of Statistical Software, Vol. 45, Issue 3, <http://www.jstatsoft.org/v45/i03>.

VAN DE WERFHORST, H G and de Graaf, N D (2004) 'The sources of political orientations in post-industrial society: social class and education revisited', British Journal of Sociology, Vol. 55, p. 211-235. [doi://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00016.x]

ZUKIN, C, Keeter, S, Andolina, M, Jenkins, K and Delli Capini, M X (2006) A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.